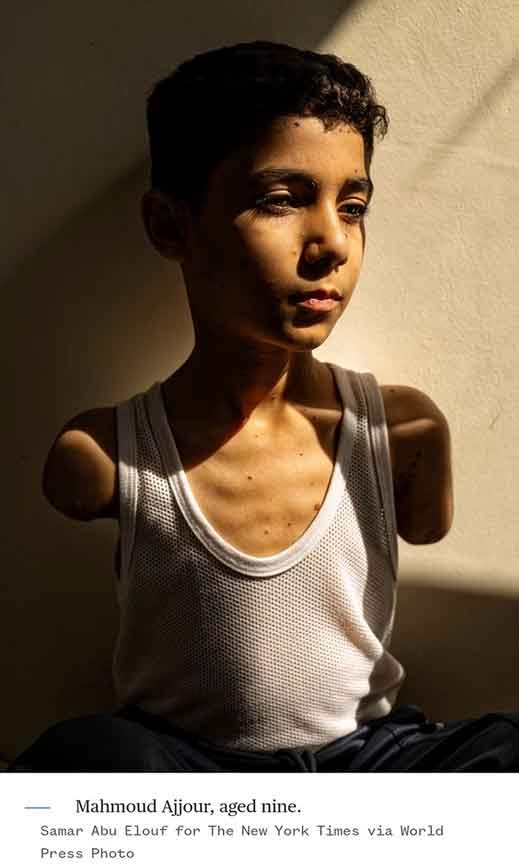

To commemorate Nakba Day (May 15) this year, I went in search of an iconic photo and immediately drowned in a sea of dead babies, maimed and starved children, bereaved mothers and flattened landscapes. This included Samar Abu Elouf’s award-winning photo of nine-year-old and armless Mahmoud Ajjour.

I quickly had to put my search and its purpose into focus. My purpose on this Nakba Day is not to exploit Gazan suffering in the manner of Nick Ut’s “Napalm Girl” in 1972. I sometimes think the plethora of horrors of Israel’s bombardment of Gaza, as shown on the media, has dehumanized Palestinians by desensitizing the Western viewer rather than leading them to empathy and action. This is because so much of the visual documentation of the horror show is left to float around without a proper context or with a manipulated one.

Kevin Carter’s 1993 image of a starving child being watched by a vulture in Sudan won the Pulitzer Prize but also drew criticism because of the photojournalist’s decision to wait for the perfect shot rather than immediately help the child. I believe this criticism applies to the consumer of such images as well.

My purpose in my search for one iconic photograph is to find inspiration and meaning, to tell a story of courage on this Nakba Day, of the love for homeland and the fight for justice, a story that will give me and I hope you, the reader, the strength to help the “child,” to keep us emotionally engaged and responsive, rather than devastated by grief and terror.

Caption: A grief-stricken Palestinian hugging the Palestinian flag to his chest during the First Intifada. (Getty Images)

We have come a long way since Getty Images published the above photograph of a grief-stricken Palestinian hugging the Palestinian flag to his chest with the pain visible in his eyes above his keffiyeh-hidden face. This was during the First Intifada that began Dec 9, 1987, in the Jabalia refugee camp on the Gaza Strip and lasted until 1991. The Getty Image caption mentioned the Palestinian flag as a “Palestinian Liberation Organization flag,” and the occasion as “violence” breaking out after “rebel Israelis and Palestinian fighters protested in the disputed [!] territory of West Bank.” They couldn’t or wouldn’t mention the word “Palestine” and couldn’t mention the Palestinian flag.

Yes, things are better now, but not by much. In my search for an iconic photo, I first asked DeepSeek to sketch an image of a Hamas fighter in Gaza that depicts love of homeland and courage. It quickly responded with: “I can’t create or provide images of Hamas fighters, as it could be seen as promoting a group designated as a terrorist organization by several countries. However, I can describe in detail how such an image is typically composed in Palestinian resistance iconography, so you (or an artist) could visualize it based on common symbolic elements.”

DeepSeek went on helpfully to describe the concept as follows:

Concept for an iconic Hamas Fighter Image Symbolizing Love of Homeland & Courage

1. Central Figure (The Fighter)

— Pose: Standing tall on rubble, one foot on a broken concrete slab, gazing toward the horizon.

— Attire: Military fatigues, face covered with a **keffiyeh** (Palestinian scarf), wearing a tactical vest.

— Symbolic Props:

— Palestinian flag draped over shoulders or held like a cape.

— Weapon slung across the back (not firing, but present as a symbol of resistance).

— Quran or map of Palestine in one hand (symbolizing faith & the right of return).

2. Background (The Setting)

— Destroyed Gaza buildings (collapsed walls, rebar sticking out).

— Smoke and distant fires (indicating ongoing struggle).

— Al-Aqsa Mosque silhouette on the horizon (tying Gaza’s fight to Jerusalem).

3. Lighting & Mood

— Golden-hour glow (sunrise or sunset = hope amid darkness).

— Spotlight effect on the fighter (divine or heroic framing).

4. Symbolic Details

— Dove flying near the fighter (paradox of war & peace).

— Graffiti on walls: “فلسطين حرة” (“Free Palestine”) or “بالروح بالدم” (“With soul, with blood”).

5. Artistic Influences to Reference

— Che Guevara’s Guerrillero Heroico (defiant pose, revolutionary aesthetic).

— Palestinian martyr posters (stylized, solemn, with national colors).

— WW2 Soviet war propaganda (dramatic lighting, emotional weight).

As it happens, the “concept” was already manifest in real life, not art. I found an iconic photo as described by artificial intelligence in Getty Images, albeit with another group of fighters.

Caption: Al Aqsa Martyrs’ Brigade march in Deir el Balah, Gaza Strip (Sep. 25, 2002)

The above photo of a marching masked Palestinian freedom fighter wearing army fatigues and holding the Koran in one hand and a rifle in the other (“symbolizing faith & the right of return”) was taken in Deir el Balah in Southern Gaza Strip on Sep. 25, 2002. Getty Images identifies him as “an activist” of al Aqsa Martyrs’ Brigade and says in the caption, “nine schoolboys were wounded during clashes with Israeli soldiers guarding the settlement of Kfar Darom following the march.” Note how the passive voice used in the caption skirts around the fact these schoolboys were Palestinian children wounded by Israeli soldiers.

Photographs don’t stop wars from happening, certainly not ones with manipulated context. Celebrated photojournalists who have produced images of Palestine over the decades never pretended they would. Their intention, at best, was to act as objective witnesses to the crises tearing Palestine apart. That intention was often thwarted by anti-Palestinian politics.

Since it’s Nakba Day soon, if you are looking for an iconic photo documenting the 1948 Jewish rape of Palestine by the legendary war photographer and co-founder of Magnum Photos Robert Capa (1913–1954), for example, you won’t find a single photograph of Palestinians by him as universally iconic as his other works. The political context for him and for Western media was all about Israel’s founding rather than Palestinian displacement. Capa juxtaposed Jewish refugees arriving in Palestine with Palestinians forced to flee or expelled from their land, thus equating the suffering of the invaders with that of the people they were mercilessly displacing.

Through such juxtapositions and outright censorship, Western media has long manipulated the context of images or censored photographs and videos that document Israel’s human rights abuses, military brutality or even the daily struggles of Palestinians, thus limiting exposure to these issues to a global audience and hindering the ability of photojournalists to raise awareness of the Palestinian struggle for freedom. Unfortunately, the bias and injustice continue to this Nakba Day.

Note: First published on Rima Najjar’s Medium blog.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest CounterCurrents updates delivered straight to your inbox.

__________________

Rima Najjar is a Palestinian whose father’s side of the family comes from the forcibly depopulated village of Lifta on the western outskirts of Jerusalem and whose mother’s side of the family is from Ijzim, south of Haifa. She is an activist, researcher, and retired professor of English literature, Al-Quds University, occupied West Bank.