In Pakistan, the drumbeat of democracy often rings hollow. While elections are held and parliaments are formed, a different, darker narrative unfolds in parallel — one marked by the systematic silencing of dissent, the marginalization of minority voices, and the repression of those who refuse to conform to the dominant ideological order. The victims range from journalists and human rights defenders to ethnic and religious minorities, and the suppression extends far beyond censorship, reaching into the realm of enforced disappearances, legal persecution, and outright violence.

This article delves into the multifaceted ways in which Pakistan has silenced “the Others” — those who fall outside or challenge the mainstream state narrative. It examines how power structures, especially the military establishment, use both legal and extralegal means to control public discourse and suppress diversity, and how such policies are undermining the possibility of a pluralistic and democratic society.

Historical Context: Constructing the “Other”

Since its inception in 1947, Pakistan has struggled with the question of national identity. Carved out of British India as a homeland for Muslims, the country faced an identity crisis rooted in its religious foundations. Was it to be a secular Muslim-majority state, or an Islamic theocracy? This ambiguity gave rise to an exclusionary form of nationalism that defined “the nation” by narrowing religious, linguistic, and ideological boundaries.

In the early decades, non-Muslim minorities such as Hindus, Christians, and Ahmadis were progressively pushed to the margins. The Second Amendment to the Constitution in 1974, which declared Ahmadis as non-Muslims, was a turning point. This legal disenfranchisement institutionalized religious discrimination and emboldened extremist groups to target these communities with impunity. The introduction of blasphemy laws under General Zia-ul-Haq’s military regime in the 1980s further weaponized religion against dissenters and minorities.

Enforced Disappearances and the Specter of Fear

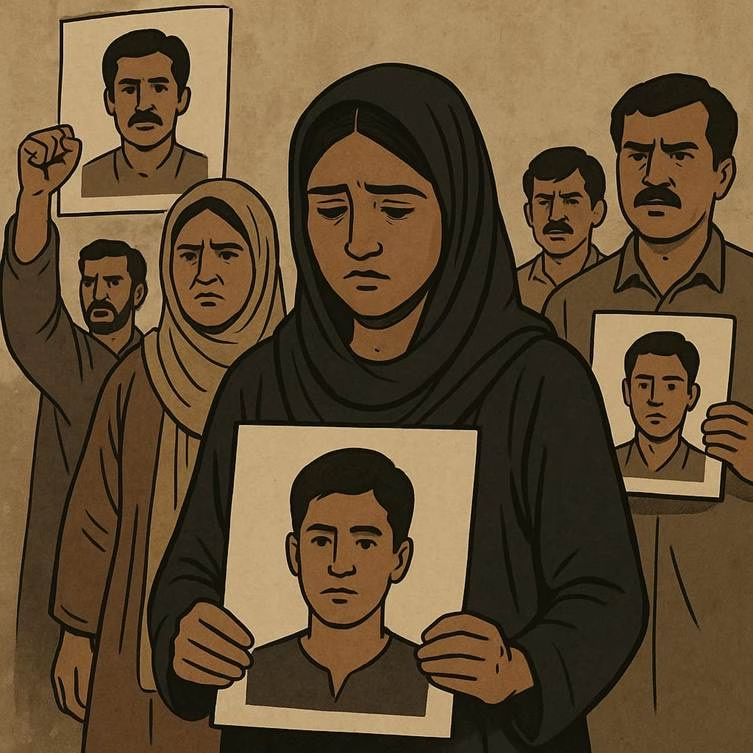

In contemporary Pakistan, enforced disappearances have become a terrifyingly routine method for silencing voices perceived as threats to state interests. According to the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan (HRCP), over 8,000 cases of enforced disappearances have been reported to the Commission of Inquiry on Enforced Disappearances since 2011. Hundreds remain unresolved.

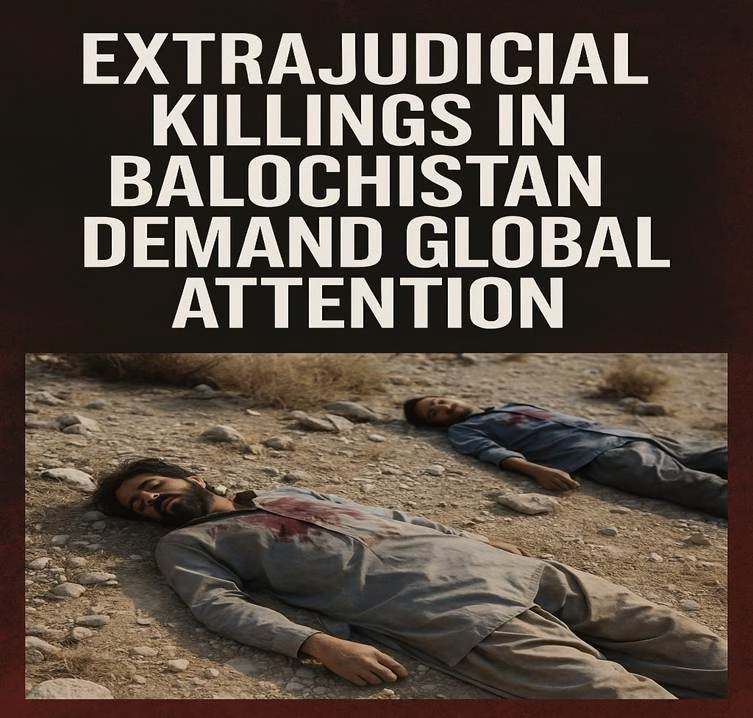

Baloch nationalists have borne the brunt of this repression. Students, writers, poets, and activists have been abducted — often in broad daylight — never to be seen again. Mass graves discovered in Khuzdar and other districts testify to extrajudicial killings. The state’s heavy-handedness in Balochistan, framed under the guise of national security, has only fueled resentment and alienation.

Even in major cities like Lahore and Islamabad, bloggers like Salman Haider and Waqas Goraya — known for their criticism of the military and religious extremism — have been abducted by unknown agencies. Their temporary releases were not victories, but warnings.

This is not just censorship — it is the manufacturing of terror through absence. The message is unmistakable: speak out, and you will vanish.

Suppressing Media and Independent Journalism

A free press is the cornerstone of any democracy. Yet in Pakistan, the media operates under an invisible but palpable leash. Journalists critical of the military or those who report on sensitive issues such as enforced disappearances, religious persecution, or military land grabs often face intimidation, job loss, or violence.

Geo TV, one of the largest media networks in Pakistan, was taken off-air in several cities in 2018 after broadcasting interviews with opposition leaders and airing criticism of the army. Dawn, the country’s oldest English-language daily, has faced advertising boycotts and physical distribution blockades for publishing investigative stories about civil-military tensions.

The assaults are not metaphorical. In 2021, journalist Asad Toor was beaten in his own home by masked men. Hamid Mir was taken off air after delivering a speech in support of fellow journalists. Matiullah Jan was abducted in broad daylight from outside a school in Islamabad.

Behind the scenes, the military’s media wing, ISPR (Inter-Services Public Relations), acts as the real censor board — dictating editorial lines, threatening proprietors, and flooding digital spaces with coordinated troll attacks. In Pakistan, journalism is not just a job; it’s a risk to life.

Blasphemy Laws: A Tool for Persecution

Pakistan’s blasphemy laws — particularly Sections 295 and 298 of the Penal Code — are among the most abused legal provisions in the country. While intended to protect religious sentiments, they have become blunt instruments of personal vendetta, vigilante violence, and state-endorsed religious persecution.

According to the Center for Social Justice, over 1,850 people were accused of blasphemy between 1987 and 2021. Most of the accused were from religious minorities — Christians, Hindus, and Ahmadis. Dozens have been lynched before any trial could take place.

Asia Bibi’s case remains infamous, but hardly isolated. In 2017, Mashal Khan, a university student in Mardan, was falsely accused of blasphemy and lynched by a mob — many of whom were his own classmates. The state’s response was muted, the convictions rare.

An accusation alone is often enough to destroy lives — a punishment without process, a sentence without law.

Ethnic and Linguistic Marginalization

The Pakistani state’s obsession with a monolithic national identity has come at the expense of its rich ethnic and linguistic diversity. From the 1971 secession of East Pakistan (Bangladesh) to the ongoing struggles in Balochistan, Sindh, and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, the state has repeatedly labeled calls for autonomy as treasonous.

Movements like the Pashtun Tahafuz Movement (PTM) have been met with censorship, arrests, and violence — despite being peaceful. Their demands for accountability for extrajudicial killings and land mine removals are routinely dismissed as foreign conspiracies.

Meanwhile, regional languages like Balochi, Pashto, and Sindhi are excluded from educational curricula and broadcast media. In 2019, students in Punjab protesting for the inclusion of regional languages in textbooks were beaten and arrested.

To erase a language is to erase a people. The cultural homogenization pursued by the state is not unintentional — it is strategic erasure.

Feminist and LGBTQ+ Voices Under Threat

Gender-based activism in Pakistan faces a double bind: from the state, and from an increasingly radicalized society. Aurat March, held annually since 2018, has triggered violent backlash. Activists have been accused of blasphemy, sexually harassed, and in some cases, threatened with death — all for demanding bodily autonomy and equality.

LGBTQ+ communities, meanwhile, live in enforced invisibility. Trans persons are frequently assaulted or killed. Despite the 2018 Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Act, enforcement is nonexistent. Advocacy for queer rights remains taboo, and activists fear arrest under colonial-era anti-sodomy laws.

Silence here is not just encouraged — it is legislated.

Civil Society and Academia: Under Siege

Universities, once havens for critical thought, are now tightly surveilled spaces. Professors have been fired or blacklisted for critiquing the military or organizing seminars on missing persons. In 2021, a seminar on Balochistan at Lahore University of Management Sciences (LUMS) was abruptly canceled under pressure from intelligence agencies.

NGOs, particularly those receiving foreign funding, face bureaucratic strangulation. In 2018 alone, more than 18 international NGOs were expelled from Pakistan. The state often accuses them of “anti-state activities” — a label so vague it can be stretched to fit any dissent.

The message is clear: even civil dialogue is unacceptable if it questions the custodians of power.

The Digital Frontier and Surveillance

As the internet becomes a vital space for resistance, the state has adopted new instruments of control. The Prevention of Electronic Crimes Act (PECA) has been used to arrest critics of the military, block websites, and stifle online campaigns.

In 2022, internet shutdowns were reported across several districts in Balochistan during protests. According to Access Now, Pakistan ranked among the top countries for politically motivated internet disruptions.

Surveillance, both digital and physical, is routine. Activists report being followed, phones tapped, and emails intercepted. In Pakistan, privacy is a luxury — and dissent, a liability.

Conclusion: The Cost of Silence

In Pakistan, silencing the others is not an unfortunate side-effect of governance — it is a foundational strategy. The state, particularly its military-intelligence complex, has institutionalized the suppression of dissent in the name of unity, religion, and security.

But repression breeds resistance. From Baloch students protesting disappearances, to feminists marching despite death threats, to journalists documenting truth in the face of peril — the struggle persists. Civil courage still flickers amid the darkness.

The international community must not look away. Aid and diplomatic engagement should be contingent on the protection of civil liberties. Silence — whether from citizens or allies — only enables more silence.

In the end, a nation that fears voices of its own people is not defending itself — it is destroying itself from within.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest CounterCurrents updates delivered straight to your inbox.

Ashish Singh has finished his Ph.D. coursework in political science from the NRU-HSE, Moscow, Russia. He has previously studied at Oslo Metropolitan University, Norway; and TISS, Mumbai.