“It will take time to adjust. So be patient. It’s no less than your rebirth.” Those words of a wise uncle still echo into my memory. Even though they were said to me more than two decades ago, they are still relevant, maybe because I haven’t yet reached where I wanted to be.

Things have certainly changed since then, but not for me personally. I still find myself stuck in time. My hope is fading as I continue to age. I have already crossed half a century. When you are young, energetic and single, you have no responsibility, but more opportunities and enough capacity to take risks and make experiments. This seems impossible when you have greying hair with some underlying health issues. It’s rather time for my grown up kids to fulfill their dreams, and I know they will. One of them has already started working after finishing his university, while the younger one is about to complete her high school. They both got good educations.

My wife too made a successful career. She got a better job than me and served in a senior government position. Even today she is the main bread winner. I never earned more than $30,000 a year while working as a radio anchor. I have always loved this job and cannot think of working outside the media industry, but I too have had some expectations. Often people say that I have nothing to complain about because of the achievements of my wife, but I also have a case. “After all, it was your choice to make this country home”, many of them frequently point out. I honestly cannot defend myself when it comes to that.

Actually, I had no real reason to move to Canada, except to live a more comfortable life. Affordability was a huge problem for our middle class family back in India. I worked as a journalist, and my wife was a social worker with Red Cross. Our son was two-and-a-half years old when we decided to migrate, even though we had no compulsion. As a reporter, I had annoyed some powerful people in a corrupt system, but it wasn’t a life and death situation. I could have easily stayed back to continue working with passion for a limited income. I can understand the situation of political refugees, but mine wasn’t at all as difficult or precarious.

Some friends did try to make me understand that I rather remain in India and contribute to the world around me through my work, but partly due to family pressure and partly due to my own economic status and strangulating socio-political circumstances, I decided to leave.

Once we were here, it was hard to find a job in my own profession. For some time I had to work with a taxi company in Vancouver as a gasman and call taker. My wife got a job with an organization that provided 24/7counselling service over the phone to victims of domestic violence and substance abuse.

Fortunately, I got a job with a Punjabi radio station a few months later. I felt on top of the world, doing news and current affairs, after being either without work for months or doing odd jobs in a non-journalistic field. This had left me depressed, when that uncle of my wife told me to wait, as moving to another country was like a new birth. He gave us hope of a better and bright future, as he himself was a well-established businessman who initially worked as a labourer after coming to this part of the world.

“You have to start everything from scratch.” We followed his advice seriously, since he had helped us by filling our first rented accommodation with second hand furniture so that we could begin our life smoothly. When I got my radio job, he commented to cheer me up: “Remember what I told you?”

I remained with that radio station for thirteen years. All through this time we changed four different houses, two basement suites and one apartment before finally settling down in a bigger home of our own, but never located ourselves away from 72nd Avenue. Our daughter was born after we shifted to this house, which is so close to a beautiful wooded area where I go for my daily walk.

When we first started living in Surrey, I remember having written an email to my father telling him how almost everyone in our neighbourhood speaks Punjabi. He was delighted to hear that there was a Gurdwara near our home, and many Desi restaurants with Punjabi signs outside. He felt assured that we won’t be homesick.

In fact, our apartment was right in the middle of this ghetto. We often walked over to Cineplex next door to watch Punjabi and Hindi movies. That doesn’t mean we didn’t see Hollywood films. We took our son to watch Finding Nemo, a children’s movie about a fish. We were so impressed by the story that we decided to get one fish as a pet and named her after Nemo. Once we accidentally left her in her jar at our old basement suite when we shifted to our apartment. Upon realizing our mistake, I drove back late in the evening to bring her home. When she died, our son kept on crying, and pleaded to take it to a doctor. We never had another pet after that.

In spite of my efforts to get into the mainstream media, I couldn’t break in. All attempts to get a degree in journalism at university and a technology college offering a program in broadcasting proved unsuccessful, even though I had a master’s degree from back home and a lot of work experience. Ironically, I was a reporter for an English newspaper in Punjab, but here it was the Punjabi radio station that provided me a platform instead of English media.

I did freelance work for a few weeklies for several years, but then the freelance journalism market dried up and I couldn’t make an additional income anymore. It goes to the credit of my wife who continued to support me and encourage me to follow my heart and not to worry about the money.

As the days turned into months and months into years, I began finding myself as a complete misfit, who didn’t belong anywhere. The community we lived in was polarized on religious and caste lines. People held regressive views about women and often focused more on the politics of India. In my open line talk shows, the issues related to India were always more popular than the local ones. Whenever I took an editorial position against the caste system or gender discrimination, many of the callers turned hostile. Some of my colleagues also mocked me for taking unpopular positions. I began wondering: are we really living in a foreign land or still there in Punjab?

The day we brought our daughter home after her birth in the hospital, we saw a police barricade outside a house in our neighbouring street. I later came to know that it was a Punjabi household. The man was accused of killing his daughter. I went to see the family to cover the story, and found the couple didn’t have a male child, only daughters. I didn’t want to be judgmental, but female infanticide has been something common in India.

I used to ask myself, why we had to come to Canada if we had to see all this. Maybe I should have stayed there to do more meaningful work. My wife faced a lot of backlash, going to different radio stations to educate Punjabi women about their rights and resources available to get out of abusive relationships. Later, when she became politically involved and ran for the provincial legislature, she became a victim of misogyny, mostly from our own community members. Some people shamelessly commented that it was me who was behind her and she had no credentials of her own. Others discouraged her from joining politics, saying this wasn’t something for the women, without knowing that she comes from a political family. Her maternal grandfather was a communist playwright who had participated in the freedom movement, and her father is a veteran Marxist. My family had never been political, and it was she who introduced me to left movements. It was through her I learned about Darshan Singh Canadian and others like him. He was killed by the Khalistanis in India, where he went back to join the communist party after spending ten years in Canada, where he fought for the right to vote. Its because of his efforts that she was able to reach the legislature. She helped in shaping my views in support of diversity, equality and inclusion. After having been an MLA for two terms, she lost the election for advocating for the rights of the third gender.

These episodes left me thinking, why am I here in the first place? Why do these folks who still believe in their orthodox value system, and consider it to be the best, not just go back? But why would they, when they have found their allies among men like Trump?

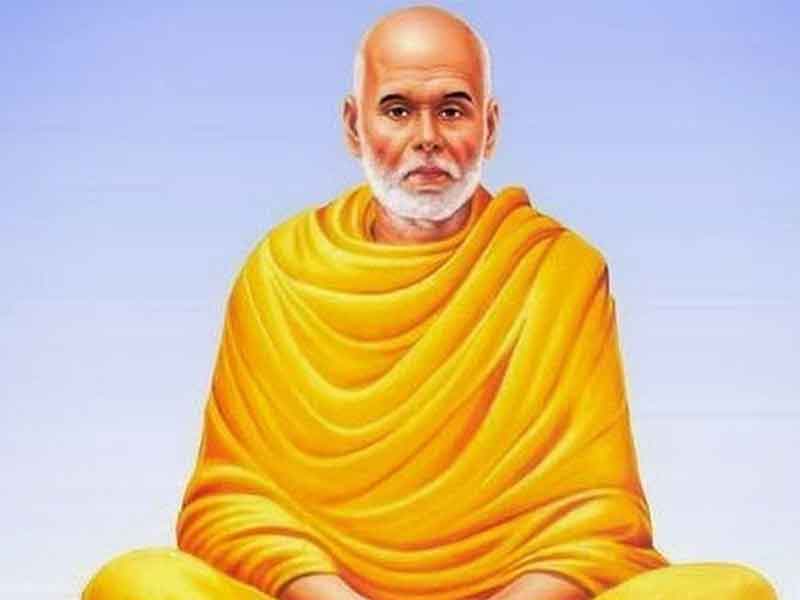

When the City of Surrey named a street near our apartment after Guru Nanak, and the City Hall in Vancouver celebrated his birth anniversary, everyone applauded. But no one thought that if a Eurocentric setting can give space to our icons, why can’t we also become a little more open? I used to think of writing a story on this new street leading to a gurdwara, whose leader in spite of being known for his liberal views against fundamentalists was also against the rights of the third gender. For him there were only two genders, men and women. He had no realization that by doing so he was trying to please the same group of people who had killed a temple keeper inside the gurdwara before I came to Canada.

Nirmal Singh Gill was murdered by the neo-Nazis, although the gurdwara leader had blamed the fundamentalists even before the investigation was complete. It’s easy to talk about Guru Nanak, but way more challenging to be his true follower. He had not only defended the rights of women, but also stood up against tyrants and taught his disciples to earn an honest living and share whatever you earn.

And yet the Gurdwara leaders went so far as to let Indian consulate officials hold their national events inside the premises, ignoring objections from many Sikhs who had fled to Canada to save themselves from persecution by the Indian government.

We used to frequently go to the gurdwara, which was within walking distance, to have langar on tables and chairs. Because of our progressive background we felt comfortable at this gurdwara, which did not follow a strict religious code of serving the community kitchen meal on the floor. This continued for a long time, until the so-called moderates lost the election, and its control went into the hands of the fundamentalists.

As my work situation remained stagnant with no scope of growth, I began writing books and started my own magazine. But this brought even more problems, when I started reporting on the Air India trial. I was candidly criticizing those involved in the bombings that left more than 300 innocent people dead. One of the two suspects had openly threatened to kill 50,000 Hindus to avenge the massacre of Sikhs in India in 1984.

The community was badly divided. Some said Sikhs never did it, and this was an Indian conspiracy to defame their struggle for justice and freedom; others said this was done by the fundamentalists to avenge the actions of the government in New Delhi. Being critical of extremism and those accused, I became a target of hate and began receiving threats. My only crime was that I invited the victims’ families for radio interviews, authored a book about them, and once read out the names of those killed on air as a tribute, besides condemning those who celebrated the acquittal of the two suspects. They were already riled up because of my sympathies with the communists like Canadian, and others who were killed by the extremists in Punjab; my commentary on Air India added fuel to the fire. The matter was reported to the police, but nothing untoward happened and everything settled down eventually. But the complete lack of empathy toward the families in the community who lost their loved ones was appalling. Even my Sikh family physician shocked me, by asking why I am so critical of the community. I asked him, does he discriminate against his non-Sikh patients? He looked at me in silence. I had to tell him that as a journalist, I am not supposed to be biased, and whoever does anything wrong, whether or not he is from my own community, needs to be held accountable.

This was being noticed by the moderates and the leaders of a Mandir. They began trying to woo me, and so did the people at the Indian consulate. Our relations remained cordial until Modi became the Prime Minister of India. As a Hindu extremist to the core, he was determined to turn our home country into a Hindu nation. Earlier he had orchestrated the massacre of Muslims in Gujarat where he was the Chief Minister. I had been criticizing him since then, but after he ascended to the highest position, nobody wanted to hear all that.

Those who treated me like a friend now started turning their backs on me. I was branded as “anti-India” and “anti-Hindu” after I interviewed a Sikh activist, who was planning to organize a protest against Modi on his first official visit to the US. They simply overlooked the fact that I was the same person who was until then described as “anti-Sikh“ for standing up for them. Modi’s emergence turned Hindutva into a new normal, with no room for any other brand of nationalism. My employer got outraged. He did not want me to give airtime to a Khalistani. He very conveniently overlooked that I had never supported those people. I reminded him of the threats I received in the past, but to no avail. I then quit my job and was workless for some time, until I was recruited by another radio station. The new employer, despite being a Hindu woman, was fair to me and never stopped me from criticizing Modi. I covered the protest that was held against him when he visited Canada. He was welcomed by the moderates and Hindu leaders alike at the Surrey Mandir.

As time progressed and I remained critical of Modi, the Indian government prepared a dossier on me. They got more agitated as I invited guests who openly challenged Modi while being in India. Two of them came to Vancouver on my invitation, Teesta Setalvad and Rana Ayyub, brave female journalists who authored books about Modi’s complicity in the Gujarat bloodshed. Teesta was thrown behind bars on trumped up charges. Now even traveling back to India seemed to have become difficult.

As if this was not enough, the Modi supporters began trying to isolate my wife. They shouted her down during special prayers held at the Surrey Mandir for Indian soldiers who were killed in a militant attack in Kashmir. They did not let her continue her speech when she requested them not to raise “blood for blood slogans” against Pakistan in a place of worship. They openly announced their decision to unseat her in the next election. All this further reinforced my sense of guilt and repentance. I began cursing myself for leaving my country when it needed me the most. I was envious of those who were fighting against Modi at the grassroots level.

Once during a public event, I said that we are all deserters; instead of fighting against repression like Nanak, who discouraged renunciation, we have fled from India. Some people began yelling at me for saying that. The last time I went to India was to see my father who was battling with cancer. After his death during that visit, I never went back. My urge to go back and restart my work where I left refuses to die, but I sometimes feel that I have burnt all my bridges. What became the last straw was yet to come.

One of the two Air India suspects, Sikh millionaire Ripudaman Singh Malik, was murdered in broad daylight. Before that he had visited India and met the head of the Indian spy agency R&AW, and shortly after coming back to Canada he wrote a letter of support to Modi. In his death, Malik became a victim for Modi supporters who began blaming Khalistanis for the killing.

I was recovering from a procedure after a minor heart attack, but I raised questions through my writings and radio show: why did the Indian government, which often blames Canada for giving refuge to those involved in the bombings, let this man travel to their country unchallenged and meet an intelligence officer? Those who shed crocodile tears for the victims of Air India were completely mum about this hypocrisy of Modi government, and looked away while I had to deal with planted news items accusing me of being a provocateur against Malik. I came to know about the dossier on me around this time.

If this wasn’t enough, the Sikh activist whose interview led to my departure from the radio job was now on the hit list of the Indian spies. Luckily, the plot was exposed, and one man was held and brought back to the US for trial. But one of his associates wasn’t so lucky. Hardeep Singh Nijjar, who was now the President of the Gurdwara near 72nd Avenue, was shot to death. It was Father’s Day and I was missing my dad, when in the evening my wife came running into my room. With her iPhone in hand, she was following X where the news of his murder was posted. Breaking my train of thought, she hysterically announced, “Someone has killed Hardeep“. She had a personal rapport with him as well. Being a politician, she had been to his events a few times. The Indian government had been accusing him of trying to establish Khalistan through violent means, and was asking for his extradition.

I had interacted with Nijjar a number of times, found him an honest, helpful and soft spoken man. Although we weren’t on the same page, I often had him on air. By this time, I was also wearing another hat, of an activist who desperately wanted to draw the attention of Canadians to what Modi was up to. Hardeep was one of a few community leaders who came to our support. He showed up at our rallies, and once organized prayers for Indigenous children when unmarked graves were found near the former site of a residential school. On one occasion, he personally came to the senior centre building at the gurdwara to install the picture of Nirmal Singh Gill, a moderate who was beaten to death by the white supremacists. He did it on our request, after his picture was lost and people who ran the centre weren’t letting us reinstall it due to personal grudges. That’s how we became acquaintances.

Exactly a month before his death, he told me in an interview how he saw his end coming, as Indian agents were active everywhere. I was at the gurdwara when his body was brought into the casket, so that people could pay their last respects before his funeral. There was no parking space left. People were raising slogans for him. There were times when we used to come to this place for solace, but today it was all mourning. Back then, in the same parking lot where an Indian tricolour used to be raised, one could see a flood of Khalistani flags. One of his supporters offered me to hold a flag, but I politely refused by folding both my hands. Posters accusing Modi of killing him went up, as calls were made for a public inquiry into the foreign intelligence being involved in the murder. Months later, when Prime Minister Trudeau made a statement saying that Indian agents could be involved in the incident, the Modi government reacted sharply.

Trudeau. who has been indifferent to our campaigns to make him speak out against Modi for the growing attacks on minorities and political dissidents in India, finally stood up. Hardeep’s death became a catalyst. What our rallies and protests could not achieve until now was gained by his sacrifice. Obviously, Modi supporters didn’t like this. and began circulating my picture with Nijjar on X. They also came after my wife who was one of the few politicians of Indian heritage who showed up at his memorial service. Others were scared enough not to annoy the Indian establishment. Whatever little hope I was left with to go back to my birthplace became diminished. Maybe the work that needed to be done there needs to be completed here in exile. But I still feel myself to be an outsider, despite being a citizen of my adopted country. Maybe I am a traitor to both lands, or maybe not. But Trudeau’s gamble, as some call it, for the sake of one human life, unlike Modi who has blood on his hands, compels me to think now this is my home. Maybe his successor’s decision to invite Modi to start business relations afresh is a sign that the fight isn’t over yet, wherever I choose to live.

Gurpreet Singh is a Canadian journalist