“Unka marzee hai hum jeeyenge… hum idhar rahenge,” (It is their choice, how we live, whether we can stay in this city) says Poonam Vishwakarma, a young woman, sitting in a makeshift shelter on the pavement of the swanky Hiranandani complex, Powai, Mumbai.

Her already precarious situation, as wife of a construction worker, was exacerbated by the brutal demolition of their home and loss of most of their possessions on June 6. Private security guards of a noted developer, N Hiranandani, along with police and officials from Mumbai’s civic body_the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation_ bulldozed hutments of some 650 families of Jai Bhim Nagar, unleashing brutal violence.

Staging a protest, the inhabitants have been living or sitting on the pavements, next to their colony, with makeshift tents of just blue tarpaulin sheets as protection against the pouring rain, for more than a month.

When I visited on July 23, Vishwakarma spoke of the constant dampness which affects them, the inability to dry washed clothes, to cook properly, the mosquitoes and the lack of any lights which prevent her son Netak Babloo from doing his homework. Weighing uppermost on her mind is their uncertain future.

“Many people have left taking up temporary accommodation in rooms, although they come here every day. I had just returned from our native village in Uttar Pradesh when this happened. What do we do? Go back to the village? Babloo’s father is a construction worker, he has lived and worked here for over 25 years.”

She points to the high rise buildings occupied by the upper end of society and says Babloo’s father used to single them out with pride as he had done the fittings for them.

“We belong to the Vishwakarma community. We used to be revered for our work. Now we are pushed out.”

The manner in which the construction workers were initially deployed and even housed in the labour camp constructed by the prominent developer and builder of Powai and then rendered homeless is the bitter story of Mumbai, India’s financial and business centre.

As Rahul Singh wrote in the Lawyers Collective way back in 2000,

“Slum dwellers have become an integral part of urban life. It is quite obvious that without them the present opulence visible in the city could not have been.”

They work in the construction sites, in households and as drivers. The city without any hesitation embraces them when it needs them.

“But when the same people make any attempt to find a niche for themselves they are treated as unwanted elements.”

More than three decades after the landmark Supreme Court decision in the Olga Tellis case (AIR1986 SC180) whereby the right to livelihood was upheld, there is no honest effort to rehabilitate slum dwellers and provide housing.

In fact, as the recent evictions of Jai Bhim Nagar reveal, civic and state authorities collude with developers and builders to carry out lawless evictions. A High Court bench hearing an appeal by 28 residents of Jai Bhim Nagar pulled up the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC) and sought an explanation for the manner of demolitions despite the GR preventing such evictions during the monsoons from June 1 to September 30. The bench ordered the public prosecutor to conduct inquiries and said “if there is prima facie something amiss, we will look into it.”

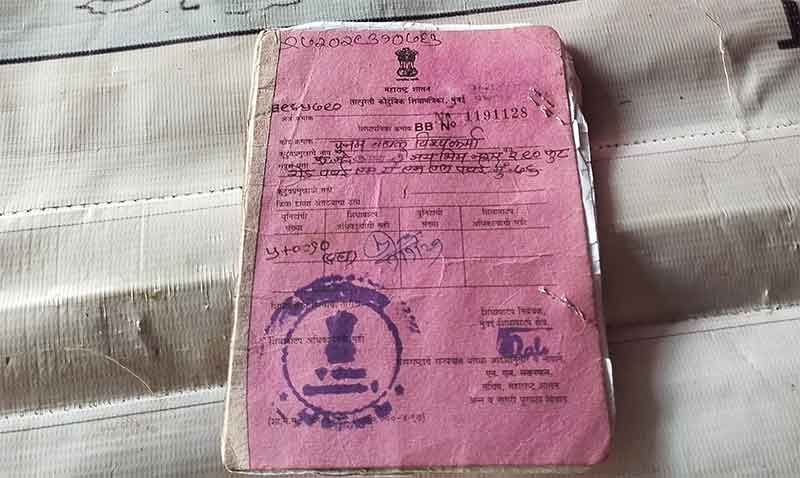

The residents say they have been living in the area for decades and have the necessary legal documents. Vishwakarma showed me her ration card and an elderly gentleman Prabhakar Basvanta Tore, who had worked as a construction worker, told me his ration card dated back to 1987.

Housing activists also point out how the land on which Jai Bhim Nagar is sited is part of property which has multiple contestations for ownership. Shubham, of Jan Haq Sangharsh Samiti, sketches a brief history.

Jai Bhim Nagar is part of lands that originally belonged to Tara Swaroop who gifted it to her son Ajay Mohan. He, in turn, sold it to 10 different people in various pieces. It is learnt that Ajay Mohan objected after the 10 people converted the land into non-agricultural use and their names were removed. The land was then sold again.

Meanwhile, in 1984, the government signed a pact with the Mumbai Metropolitan Region Development Authority (MMRRDA) to develop the lands and power of attorney for land lease was given to Hiranandani, Powai’s prominent developer, for construction of affordable housing.

(Later, a case was registered in 1986 against Hiranandani for fraud when it was found that instead of selling the single unit houses in the buildings he constructed to those with low income, they were combined and flats with larger areas were sold instead to the affluent classes.)

In the case of Jai Bhim Nagar, when the developer put up a board for construction, some of the original 10 buyers went to court and a lengthy legal battle took place going all the way to the Supreme Court (Ajay Mohan & Ors vs H.N. Rai & Ors on 12 December, 2007).

What is noteworthy is that whilst Hiranandani’s name did not figure at all in the fight for ownership, he had still managed to utilize part of the property to set up a labour camp in 2002 for his firm’s construction workers. This came to be known as Jai Bhim Nagar. A mysterious fire took place in the camp in 2007 in which officially two persons died and at least 150 huts were destroyed.

In a curious turn, the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation, (BMC) held Hiranandani responsible for re-building. He then sent a formal request for building a labour camp and got BMC approval. It was officially constructed even though the developer had no papers for ownership of the land.

In 2014 under a new development plan the reservation was changed for construction of government offices and Hiranandani was told to evict the residents. Interestingly it is the MMRDA that should have been the appropriate agency to be given this responsibility, say activists.

In 2017, Hiranandani sent a notice for eviction to the residents of this labour camp. Some 40 of them objected and went to court. One of them, Arun Sangda, a mason , told me, “ The issue is still in court so how did the second notice go out in 2019 and how was this demolition carried out this June, giving us just two days’ notice?”

Shubham, a housing activist, points out how in another interesting twist, the state human rights commission was roped in when the son of a corporator approached it with a complaint that the labour camp and its inhabitants were violating the rights of those who lived in the posh buildings around.

The BMC claims it was under these directives of the Maharashtra human rights commission that demolitions were conducted. It must be noted though that this body has only advisory capacity and unlike a court it cannot issue orders. It is also not known how the human rights commission came to the justification that the presence of the labour camp goes against the rights of those residing in the surrounding buildings.

On June 6, the day of the demolitions, there were pitched battles between the police and the residents. It is learnt that a section had decided to resist strongly and accordingly placed chairs at the entrance on which they sat with photographs of Babasaheb.

The residents say that the developer had sent his own security guards or “bouncers” who began getting violent. The photographs were tramped upon and thereafter stone pelting and fracas took place. Additional police forces were brought in and by late afternoon, those who were resisting were forced to retreat.

The police then swung in and violent assaulted those who had not been resisting and were in the houses. Among them was Atmaram Paikrao, a labourer, who had returned from duty and was sleeping.

“Four policemen pulled me out and beat me up savagely” he said. He showed me his medical record papers and the scars visible on his legs and arms. “I still find it difficult to sleep at night,” he added.

It is reported that among those beaten was also a pregnant woman who later suffered a miscarriage.

Some of the residents have filed a case in court demanding punitive action for the assault, and demanded compensation and re settlement in the same locality. The matter is being heard in court.

The developer had offered settlement in Phue Nagar but as residents point out the land has no amenities, no transport. More significantly it is on forest land and therefore would render the re settlement illegal.

Shubham points out how increasingly evictions are being carried out by civic and other authorities without following any procedures so that people lose not just homes and possessions but also the possibility of rehabilitation.

“No surveys are being taken, no panchnama is done of every household so it is difficult to establish lawfully who lived there.”

In this recent demolition, police illegally seized and destroyed people’s possessions.

He adds that documentation is getting difficult since water and electricity connections are managed by middle men.

A number of political figures have jumped into the fray promising help or rehabilitation to the displaced people, but when I visited them on a rainy day, despair and dismay was palpable.

It may be recalled that in July 1981 when bulldozers in Mumbai ran over the 1600 pavement homes journalists like Ivan Fera, and Praful Bidwai approached the rights body, the People’s Union for Civil Liberties (PUCL) to intervene and interim relief was sought. Veteran journalist Olga Tellis went right up to the Supreme Court for rights of slumdwellers and a number of organizations took up the cause. A landmark verdict was delivered. The Supreme Court ruled that an important facet of the right to life as guaranteed in Article 21 is right to livelihood and that deprivation “would not only denude the life of its effective content and meaningfulness but it would also make life impossible to live.”

(For more on this history read https://bombaywiki.with.camp/Justice_Lentin_Visits_Kamraj_Nagar,_and_What_Happens_Next)

Unfortunately, the rights of the disadvantaged have been further denuded. There seems little or no relief. Sangda, who had filed a case back in 2017 against the first notice by Hiranandani said, “Mar rahe hai hum road pur.” (We are dying slowly on the streets…)

Paikrao added, “They (the authorities) are hoping that we will go away. They feel eventually we can be wished away.”

Freny Manecksha is a journalist