Home-based workers in India represent a significant yet often overlooked segment of the labor force. According to the International Labour Organization (ILO), there are approximately 37.4 million home-based workers in the country, comprising about 28% of the total informal workforce. These workers, predominantly women, engage in various forms of production and service activities, such as crafting garments, assembling electronics, packaging goods, and creating artisanal products from their homes. They often work on a piece-rate basis, contracted by firms, individual traders, intermediaries, or sub-contractors, and may perform tasks like stitching sleeves, sewing buttons, trimming threads, attaching drawstrings, and crafting embroidery. Despite their contributions to the final products sold in markets, home-based workers remain largely invisible in the supply chain due to their employment through a series of intermediaries, which limits their direct access to markets and recognition from companies, governments, and society at large.

The lack of visibility and recognition leaves home-based workers vulnerable to exploitation, often receiving minimal wages without access to social security, health benefits, or labor protections. Many of these workers earn far below the minimum wage and are especially susceptible to economic downturns and disruptions like the COVID-19 pandemic, which further exacerbate their precarious livelihoods. Decisions such as demonetization, GST, lockdowns impact their already impoverished conditions.

The stark reality of home based producers and their invisibility are illustrated in Neha Dixit’s book, “The Many Lives of Syeda X: The Story of an Unknown Indian.” Written in a narrative style based on the real life of a female migrant worker named Syeda a Muslim woman from Uttar Pradesh, it depicts how she navigates in the urban informal economy in Delhi. In the process, Dixit sheds light on the intersection of economic exploitation, gender discrimination, and religious marginalization that shapes the lives of many home-based workers. It is a story of systemic neglect and invisibility of the urban poor in policy, media, and popular culture.

In the 1980’s and 90’s, as India started opening up, multinational companies shifted their production sites from factories to outsourced workers who were home based producers. The employment was not direct but through a multi layered local subcontracting network. This enabled them to avoid labor laws and make more profit through outsourced work. The home based producers were indirectly employed by the MNCs and directly by sub-contractors. They worked on a piece rate basis and are paid not on time or shift basis but piece basis. They are invisible and fall outside the scope of regulatory authorities to ensure minimum wages, working conditions and social security. Many such sites of home based production sprung up such as the one in Karawal Nagar in Delhi. Syeda formed one of those home based workers.

Spanning over 30 years, Syeda took up such 50 odd jobs, primarily home based work. Syeda started helping in weaving work through rolling yarn onto bobbins and shuttles and supporting a tailor where she would do the hems, buttons, hooks and saree falls in Benares. After migrating to Delhi, she started washing clothes of foreigners in a hotel. She cleaned raisins and worked in a namkeen factory. On a piece rate wage basis she took up preparation of wooden, metal and plastic photo frames and got paid at the rate of Rs. 70 for 144 pieces. Later she shifted to preparation of door hangings, bouquets of plastic flowers, and decorative pieces out of discarded bulbs which are crocheted with wool for Rs. 60 for 144 pieces. She picked up thread and needle work, stuffed soft toys with fibre or cloth scraps and stitched them for Rs. 1 apiece. She stitched cloth bags at 50 paise per piece on a stitching machine. She embroidered sarees for Rs. 5 per piece and motifs on garments for Rs. 30 for 144 pieces. She picked up preparation of school bags at Rs. 60 for 144 pieces. Using wires and beads, she made jewellery for Rs. 50 for 144 earrings. She made plastic guns with springs for Rs. 24 for 1,000 pieces. She took up work for assembling plastic wheels. She chose work related to screen printing on wedding cards. She accepted work in a toffee packing factory, worked in a fruit processing centre. Festivals created temporary work opportunities such as during Raksha Bandhan for preparation of rakhis, preparation of mehndi cones and decorated karwas during Karwa chauth, preparation of rugs during Ramadan, preparation of strings of fairy lights during Diwali, preparation of decorative pieces and Santa dolls during Christmas, preparation of Saraswati idols during Basant Panchami. During elections, flags, keyrings and caps were prepared for various political parties. She took up preparation of football which provided her Rs. 5 per piece and in a day about 8 to 10 balls were prepared. She also ventured into bhindi making work and incense sticks.

Along with a husband who largely worked as a manual worker and children who had to be somehow educated, she struggled to make ends meet. Her children too however ended in informal work. The only way to survive in home based work was to find work through networks and take up the work on whatever wage rates they are fixed at. Switching jobs, getting fired, getting new one for the same amount, was the only way to survive. There is no regulation on decisions related to fixation of abysmal rates. It demanded a work of 14 to 16 hours a day to meet the orders and often involved also taking the help of children, which Syeda takes up from her daughter. The subcontractor would collect the finished products and hand it over to a contractor or a wholesale dealer who would deliver them to exporters for multinational companies. There was no way to negotiate for a higher piece rate wage.

The only time there was some increase seen in remuneration was during her work at Almond factory. Unprocessed Almonds and walnuts were imported into India from the US, Canada and Australia. Women home based producers such as Syeda were paid Rs. 50 for processing 23 kilos but godown owners made Rs. 125 to Rs. 150 for processing the same bag. The intervention of Badaam Mazdoor Union demanded improvement of working conditions, timely payment, taking care of medical expenses in case of accidents and starting a creche for supporting mothers. It was partially successful with an increase in wages from Rs. 50 to Rs. 60.

The book shows how child labour is commonly prevalent in home based work, which happens not due to parents but due to the poor wages and impoverished conditions. For meeting the orders of the sub-contractors or getting minimum income for survival, the parents are forced to take help of children to support them. The court decisions such as shifting factories while largely in the public interest, affects the poor more than the middle and richer classes.

Syeda’s story reflects how despite being a skilled worker who takes up multiple types of works yet remains impoverished and struggling to make ends meet on a daily basis. This book underscores the pressing need to recognize the contributions of home-based workers and ensure better working conditions and protections for this essential yet often unseen workforce. By bringing attention to their struggles and resilience, it highlights the importance of addressing the challenges faced by home-based workers and advocating for their inclusion in national labor statistics and policy discussions.

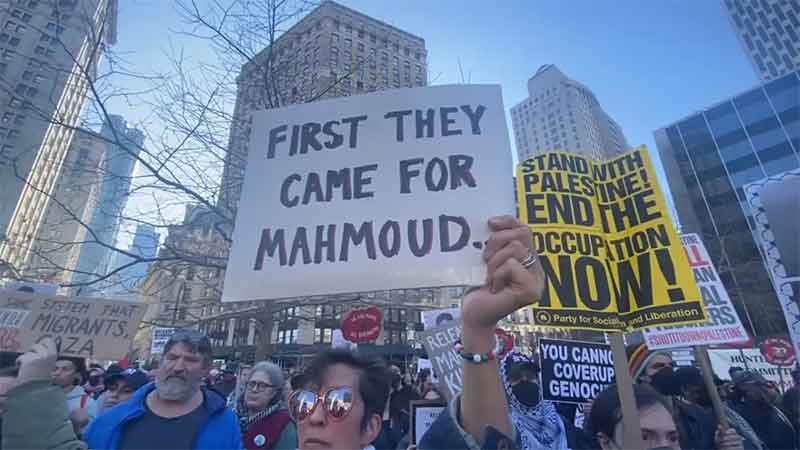

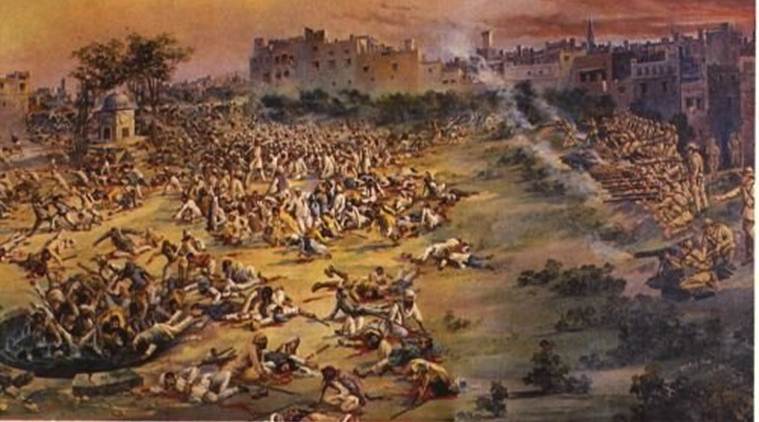

At the larger backdrop of politics of the times, it also shows instances of stigmatization, stereotyping, marginalisation of the family for being a Muslim. The Babri demolition, the Gujarat 2002 riots, the lynchings around Cow, CAA NRC, propaganda around Tablighi jamaat and their use by RSS for othering Muslims are shown. His sons despite having no criminal record, get caught in cases of any petty or large crime or terror activities. Just for being a Muslim youth, they become potential suspects. Instance of a marriage of his son getting married to a Hindu girl gets depicted as an instance of love jihad. Being referred to as a ‘Bangladeshi, Ghuspetiya’ despite having roots in India are commonly seen. The practice of some sort of untouchability particularly by upper caste Hindus with the family are also depicted.

The book’s narrative style only humanizes the statistics and also provides a voice to the millions of home-based workers whose labor is often unrecognized and undervalued. This work is an important piece that brings to light the urgent need for systemic change, advocating for fair wages, better working conditions, and social protections for this essential yet overlooked segment of the workforce. By telling Syeda’s story, Dixit challenges readers to acknowledge the dignity and rights of home-based workers and to push for policies that ensure their inclusion and protection within the broader economy.

Currently, there is no policy on women based home producers. In a draft suggestive National policy for Home based workers prepared by HNSA and WIEGO in 2017, it called for recognition of home-based workers as a distinct category of workers and their inclusion in national labour statistics and surveys. It called for extending labor laws and social protection schemes to cover home based workers. Economic empowerment was emphasized by facilitating access to credit, markets and skill development programs. Improvement of working conditions such as ensuring fair wages, timely payments, and providing occupational health and safety measures were emphasized. Promoting gender equality, equal opportunities and implementing measures to prevent discrimination and exploitation was emphasized. It also called for dedicated institutions or bodies to support and monitor implementation of policies for home-based workers.

Given the conditions of Home based women workers, it is important to pay attention to this segment.

T Navin is an independent writer