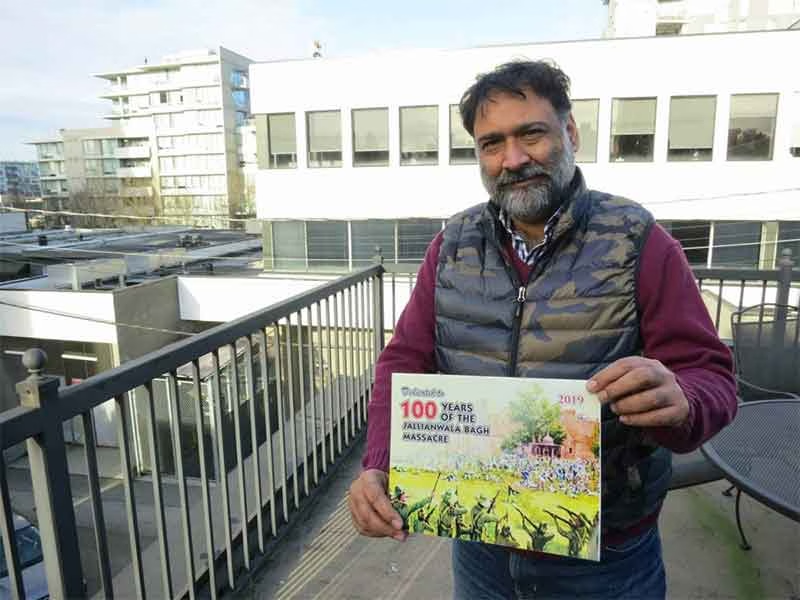

Located within walking distance from the historic Gandhi Maidan in Patna is the building of the Primary Teachers’ Association. Last Sunday (October 20), the building, situated on Exhibition Road, hosted the second Bihar state conference of Jan Lekhak Sangh, a Bahujan literary forum established in 2016. Upon entering the aging building, I encountered an elderly man, brimming with the energy of youth. At 64, Mahendra Narayan Pankaj, the general secretary of Jan Lekhak Sangh, was seen coordinating most of the event’s activities with great enthusiasm.

The venue drew poets, writers, and activists, predominantly from Bahujan communities, who travelled from various parts of the country. While most attendees hailed from Bihar, West Bengal, Jharkhand, Uttar Pradesh, and Haryana, some even came from the neighbouring country of Nepal. During the day-long literary gathering, discussions focused on the relevance of Bahujan literature. In the afternoon session, a dozen poets recited their works, and in the final session, awards named after Bahujan icons such as Jyotirao Phule and Dr. B. R. Ambedkar were given to poets and writers.

Much of the credit for organizing such events for the downtrodden on a regular basis belongs to Mahendra Narayan Pankaj, affectionately known as “Pankaj ji.” He is the architect behind Jan Lekhak Sangh, which has created a space for writers from marginalized communities. Pankaj firmly believes that Bahujan communities can only achieve their rights and a dignified place in society if they actively challenge the dominant Brahminical culture. For him, the spread of Bahujan consciousness through literature and literary forums is the key to combating inequality, superstition, and harmful practices.

Despite his health challenges, Pankaj remains exceptionally active in the forum’s work. He is always available to answer questions related to the forum’s activities, and although he initially struggled with smartphones, he has now mastered their use. Though the forum faces severe financial difficulties, Pankaj frequently attempts to sustain it by contributing from his own resources. He does not hesitate to spend a substantial portion of his pension to ensure the forum’s survival.

Thanks to Mahendra Narayan Pankaj’s relentless efforts, the forum publishes an annual Hindi literary issue titled Jan Akansha. To date, seven issues of this magazine have been published, providing a platform for marginalized writers from Dalit, Adivasi, OBC, and Minority communities. The magazine features stories, poems, and other literary works, and Pankaj shoulders much of the responsibility for its content, editing, publication, and distribution.

In the seminar hall, Pankaj was seen managing the heavier responsibilities with great care. At one moment, he was coordinating activities from the podium; the next, he was at the door, warmly welcoming poets and writers as they arrived. He made sure to check whether the guests had eaten, and at times, he would pick up bottled water and ask the audience if anyone was thirsty. In his dedication to serving others, he forgot to eat or drink himself. When fatigue caught up with him, he would rest on the wooden cot placed against the wall of the seminar hall. Next to him was a large bag filled with medicine. He hadn’t been well recently and was undergoing treatment. “Now I get tired quickly. It’s because of my illness,” he confided when I sat beside him under the fan. While talking to me, he took a few pills and then drank some water.

Pankaj’s profession has been teaching, and in recognition of his contributions to education, he was honoured by the Bihar Government. Aside from teaching, literature has been his major passion. Pankaj is the author of numerous books, including Ek Yuddh, Krantiveer Chandra Shekhar Azad ki Kavya Gatha, and Nutan Sabdanushasan, a work on Hindi grammar. He follows the radical tradition of literary theory, believing in the creation of emancipatory literature. Inspired by the teachings of Jyotirao Phule, Pankaj asserts that Shudras and Ati-Shudras have been dominated by Brahminical ideology. Without spreading counter-hegemonic consciousness among Bahujans, he believes, their liberation from oppression is impossible. In his view, Bahujan literary forums are key to generating such discourse.

Born on June 1, 1960, in Bhatni village in the Madhepura district of Bihar, Pankaj experienced caste-based discrimination from a young age, as a member of a backward caste family. As he grew older, he realized that imparting education was essential to combating such discrimination. Despite facing numerous challenges, he completed his post-graduation and secured a teaching position at a government school. While he gained admiration as a teacher, his flair for writing never waned. Early on, he developed the belief that teaching should be paired with literary activities to foster Bahujan consciousness. For him, literature aimed at social change is essential to reconstruct a society based on the principles of freedom and equality.

During our conversation, Pankaj reiterated that the social and political category of “Bahujan” represents the majority of oppressed people. According to him, this group includes Dalits, Adivasis, backward castes, and minorities, who are discriminated against and oppressed by the minority upper castes. These upper castes control material resources and dominate religious, cultural, and intellectual activities. To dismantle this exploitative system, Pankaj believes it is essential to establish literary forums run by Bahujans themselves, which would work for the upliftment of the oppressed majority.

When asked why he believes that Bahujans should create and run their own literary forums, Pankaj shared his personal experiences. He explained that for a long time, he was involved with progressive literary forums, but eventually realized that the so-called progressive writers were unwilling to dismantle caste-based structures. Nor were they ready to give adequate space to writers from Dalit, Adivasi, OBC, and minority communities.

Explaining the background of the Jan Lekhak Sangh’s formation, Pankaj revealed that he had been a part of the Janwadi Lekhak Sangh for four years and had been associated with the Pragatishil Lekhak Sangh for 11 years. He alleged that despite these forums’ progressive claims, they had not rid themselves of Brahminical elements. “Discriminatory practices exist within these so-called progressive forums and the brotherhood that Dr. Ambedkar emphasized is absent. This is why people gradually leave those places and join Bahujan forums. Today, the Bahujan movements have made significant progress”, he said.

He went on to claim that caste-based discrimination is present even within all communist parties. “Brahmin writers lead these literary forums and run the parties, adhering to Manuwadi ideology. The literary forums of the communist parties are not immune to such tendencies.” As an example, Pankaj recalled an instance during the state conference of the Pragatishil Lekhak Sangh, when Bahujan writers were denied the opportunity to recite their poems. When questioned about the exclusion, he noted that these forums only allocated time and space to upper-caste writers. To explain this phenomenon, Pankaj referred to Baba Saheb Ambedkar’s belief that the annihilation of caste is a prerequisite for establishing equality. In his view, literature can play a crucial role in fostering anti-caste consciousness.

However, the rampant casteism within these so-called progressive organizations “frustrated” him, leading him to part ways with them. On January 10, 2016, he invited Bahujan writers from 12 to 13 states to the first national conference of Jan Lekhak Sangh, held in New Delhi. Since its inception, Jan Lekhak Sangh has provided a platform for marginalized writers to express themselves. Today, the forum has spread widely, with active units in 18 states. “Through our forum, we challenge Manuwadi ideology. We work on the principles of freedom and equality, adopting a people-cantered approach. Our path follows the one shown by Baba Saheb Ambedkar. We strive to build a society based on equality,” Pankaj said.

When asked to elaborate on his differences with progressive writers, Pankaj explained that he had studied Marxist literature but later found Dr. B.R. Ambedkar’s writings to be far more appealing. Ambedkar’s works resonated with him because Indian society is fundamentally structured around caste-based inequality, and without dismantling this system, true emancipation is not possible. This is why Jan Lekhak Sangh follows the path outlined by Dr. Ambedkar.

In defining Bahujan literature, Pankaj described it as a “broad” term that encompasses the struggles of marginalized communities, including Dalits, Adivasis, and minorities. Bahujan literature emphasizes that the 85% of the population who are marginalized must recognize that without struggle, power cannot be attained. Without power, these communities remain in a position of servitude. Therefore, it is essential to strengthen Bahujan movements, enabling people to become aware of their rights and to take to the streets to fight for them. In short, Pankaj highlighted that Bahujan literature reflects the harsh realities of life. It is a literature that fights against starvation and inhumane practices. In contrast to Brahminical literature, which often describes the luxuries of life, Bahujan literature expresses the pain, suffering, and struggles of Dalits, Adivasis, minorities, and other marginalized groups.

Addressing the long-standing debate on whether non-Bahujans can authentically express the pain of Bahujans, Pankaj argued that only a hungry person can truly describe the pain of hunger. “Only Bahujans are justified in writing about their own suffering. Others, sitting in their ivory towers, create artificial accounts of pain,” he said. According to Pankaj, it is highly unlikely that upper-caste writers can accurately depict the true suffering of Bahujans because they carry within them Brahminical values that have been ingrained for thousands of years, making it nearly impossible for them to liberate themselves from these beliefs.

Reflecting on the history of Hindi literature, Pankaj noted that before the era of Premchand, literature largely focused on elite issues. He credited Premchand with shifting the focus to the struggles of the common people, using literature as a tool to raise awareness and promote social change. Similarly, Bahujan literature, he explained, aims to combat hunger and promote equality in society. The slogan of Jan Lekhak Sangh is to create “pro-people” literature, and the forum works tirelessly to challenge the dominance of the elite in society.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest CounterCurrents updates delivered straight to your inbox.

Over the past eight years, Mahendra Narayan Pankaj has worked tirelessly to build Bahujan unity through Jan Lekhak Sangh. The forum regularly holds meetings and inspires hope among Bahujan writers. Once a registered body with its central office in Madhepura, the forum now has its own website and has drafted and passed its constitution. Pankaj has been the main architect behind all of these milestones.

Dr. Abhay Kumar is an independent journalist. Email: [email protected]