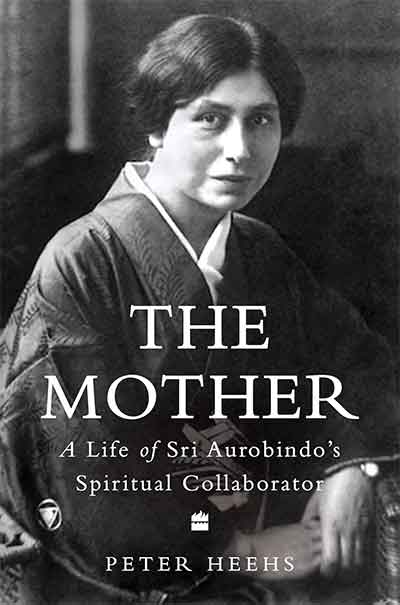

The Mother: A Life of Sri Aurobindo’s Spiritual Collaborator, Peter Heehs. Haryana: Harper Collins, 2025. Pp337.

Often we don’t know what we have come here to do. Ultimately it hardly matters whether we know it or not, so said the Mother in a conversation.

There is no evil, there’s only disequilibrium (quoted in p211)

As Sri Aurobindo saw it, the Mother embodied mainly four great aspects — Wisdom, Strength, Harmony, and Perfection, and to the four he attributed these divine names– Maheshwari, Mahakali, Mahalakshmi, and Mahasaraswati . And once in response to a question by one disciple whether he meant these as qualities of “the Mother,” he answered in the affirmative. He represented the Purusha (Soul, Spirit) element and she the qualities of the Shakti (Force, Power). From this we are to assume that the Mother was his spiritual collaborator. This might sound strange for those quite unfamiliar to the practice of the Tantric system. In their entire collaborative effort in Yoga and meditation Sri Aurobindo chose to remain behind withdrawn and silent while Mirra Alfassa aka the Mother, was active in front, setting up the Ashram first, interacting with a steady stream of disciples and visitors, and eventually organizing and creating a Trust to run the day to day affairs of the establishment . For a person who grew up in 19th century France, with a mixed lineage of Jewish and Egyptian culture, caught in the early years in the web of Occultism, Judaism and many other similar religio-mystical movements of those times, travelling widely, and finally settling down as a spiritual collaborator of Sri Aurobindo, Mirra Alfassa’s life journey does not lend itself to easy mapping. And anyway, what was actually left for a biographer to narrate? Sri Aurobindo himself has maintained that his life was not on the outside for people to see, and in a similar way most of Mirra Alfassa’s life was submerged in her inner psychic activity, and her meditations. One must be able to act without any preference, she has noted, free from all attractions and likings, basing oneself solely on the Truth that guides. (210). For her, Truth and the work of the Divine as she “psychically sensed” it were as real as objective realities were for the ordinary people, and she constantly strived to uphold both.

Born as Blanche Rachel Mirra Alfassa, to Maurice and Mathilde Alfassa, who traced their roots through the Ottoman Jewish, to Cairo, Alexandria and France, she later moved to Pondicherry and adopted India as her home.

At the outset Peter Heeh’s book, The Mother: A Life of Sri Aurobindo’s Spiritual Collaborator, could easily present itself as belonging to that genre of “Westerner-finds-spiritual-truth-in- Asia”—or just another search in secret India. Knowing the outrage his earlier book on Sri Aurobindo created among the Ashram circles, one would assume that this is just-another “such stuff.” I was a bit prejudiced when I picked up the earliest copy as it bounced out of the press and pored over it. Strangely enough it reads quite an easy- to-read account of a life lived to the full with more than enough background reading materials and references. The book has turned out to be well-researched biography of a complex personality who grew up in the midst of the fast changing art-world of nineteenth century France, deeply involved in the occult practices and meditations of obscure Cosmic teachers and gurus whose concerns were other-worldly, deeply obsessed with what happens to the physical existence after death, and the one who finally met with a genuine guru in the small French occupied territory of Pondicherry. The Mother’s journey from France to Pondicherry, from the happening centre of the art-world to the real world of a sadhak profoundly dedicated to the work of the divine, in tune with a radical mystic is quite well documented by the author of this biography.

The book is divided into two parts, the first one comprising seven chapters describing events between the years 1878 and 1926, and second part with four chapters dealing with 1927 and 1973. There is also a prologue that sets forth the writer’s arguments as to how and why the biography took its present shape and how Mirra became the Mother. “I write with the assumption that Mirra Alfassa was not born with a prevision that she would take to the spiritual life,” writes Hees. “Her sense of spiritual vocation emerged gradually over the course of five decades … Like the rest of us, she had no clear knowledge of what would happen next.”

This is in the manner of what the author classifies as the “alpha” mode of biography where the subject of the book at any given point in her life was quite in the dark about the future. The opposite of that would be the “omega” mode which as the author contents is what the usual hagiographical narrations would take. The reader of the second type of biography would already know more of what the future held for the subject much like the author of a murder mystery, and such a narration might not throw much light on what it was like for Mirra to become the Mother.

In her diaries of several years later the Mother has noted: Often we don’t know what we have come here to do. Ultimately it hardly matters whether we know it or not, so said the Mother in a conversation.

There are two types of readers who could reach for this book. The first could be some ardent devotees of Sri Aurobindo and the Mother who could be, to a certain extent, familiar with their work and writings. They could certainly end up disappointed if they manage to read through this biography, simply because they might not find here the mystery and enigma that they visualize behind the Mother’s life nor any of the charmed narratives offering explanations to those cryptic musings of the Mother. This is more of a plain narrative of occasions and situations, meetings and passings, growth and decay, laughter and love, where the Mirra whom they would not have visualized, grows up and travels, dreams and desires. The second kind of readers likely to migrate to this book would be those who have perhaps heard about the Mother of the Sri Aurobindo Ashram and would like to know about her life and work. They may not be disappointed because as I mentioned this is an easy- to- read a plain-narrative of her life, date-wise, year-wise, with details of who she met, who she dated and later married, the dress she wore, where she went what she ate etc. Hees has mentioned at many points that he was just a biographer and a historian who had access to all that Mirra has left behind, her memoirs, her dated diaries, her letters and her biographical details. Time and again he reminds the reader that he is not drawn to explain or critique her miraculous experiences and her mystical encounters nor is he trying to expound or illustrate her yogic association with her spiritual counterpart Sri Aurobindo , “a perfect synthesis of East and West.”

My task as an ‘alpha’writer, Hees writes, has been to collect, organize and arrange contingent facts in a continuous narrative (p154)

Then the question that would weigh heavy with us is what is the earthly use of a biography that sets forth plain details of day to day existence like a travel itinerary of a spiritual mind who had harbored a restless soul all along? This reminds one of writing at great length on Shakespeare’s Hamlet carefully picking up meticulous details of his breakfast, lunch and dinner menus. Or as the critic would have stated: writing a lengthy dissertation on how many children had Lady MacBeth? Or the details of the childhood of Shakespeare’s heroines.

The Mother, aka, Mirra Alfassa, was fortunate to have had the freedom to experience herself through her involvement in painting and being present at the most happening place in Europe when the great movements of Impressionism and several other important movements in painting were taking shape, and later during the first world war travelling to Japan even meeting up with Gurudev Tagore, and having had her fling through the occult terrains of Europe, and meeting up with mysterious clairvoyants like Theon and Madame Theon, getting involved in tantric and yogic practices, and later in the best part of her life meeting up with Sri Aurobindo and then dutifully following her calling. She was extremely careful in keeping the finer distinctions of Spirituality and Religion. Mirra as Hees mentions has had little trouble accepting Hindu expressions of guru worship that the Ashram gave rise to. (147) Religion as Mirra notes, is always a limitation of the spirit. People with developed minds absolutely have to leave their religions if they don’t want to be halted in their progress (quoted 217) She is extremely careful about maintaining her inner spiritual mission.” Spirituality means putting oneself entirely under the law of truth and bringing down that law of truth upon earth. That’s bound to bring a solution to all problems.”(Quoted in p221) In all these she was able to see eye to eye with Sri Aurobindo. He was extremely well read in European classical philosophy and was insightful about the finer nuances of Indian spirituality as outlined in Yogic metaphysics and Vedic mantras. She was much travelled and had exposure to practices like Occultism and those associated with Neo-Platonism. Her inner vision as explained much later through her conversations with her disciples held the essential idea of transformation of the entire material universe. She was wont to use Theosophical and Kabbalistic language which she had been exposed to in her youth and in all her travels east and west, even after fifty years.

The Mother’s prayer that was later inscribed on a plaque that was affixed to Sri Aurobindo’s samadhi: “To Thee who hast been the material envelope of our Master, to Thee our infinite gratitude. Before Thee who hast done so much for us …we bow down , and implore that we may never forget , even for a moment all we owe to Thee.”

The Ashram is the Mothers creation and would not have existed but for her, wrote Sri Aurobindo in 1935 (see p155) In 1954, Pierre Landy, a special envoy of the French government, wrote to the then French Ambassador in New Delhi, that “ in the case of Madame Alfasa, the internationally renowned spiritual guide is coupled with a formidable business woman.” (p 219) According to Hees, the Mother would not have considered this an insult. She combined in herself the yogi and the practical woman. She initiated the idea of an International University to propagate the life and teachings of Sri Aurobindo and also laid the fondations for the formation of Auroville, a township dedicated to promulgating the idea of human unity and transformation of all life. In all this she was upholding the visions and ideals of Sri Aurobindo. Her own inner experiences as she recorded and left through her many conversations with her disciples, elucidates what she called the Yoga of the World. She firmly held that Love and Truth alone existed and will be manifested. (see p 239)

According to the Mother, Auroville would be a Universal town where men and women of all nations are able to live in peace and progressive harmony , above all creeds, all politics, and all nationalities. Its aim was to realize human unity. (see 249)

Peter Heehs, as I am given to understand, was not formally schooled, and did not attend any university, but still he has produced a readable biographical document with the materials he has had access to. Although he claims to be domiciled in Pondicherry for several years his mental leanings appear to be clearly western, which of course, given his environment, are not to be demeaned in any way. His richly documented account of the Mother’s life is quite straightforward and unbiased. Sentences like: Mirra Alfassa was born in France because her mother was living in France when she was born (xiii) ; I am a historian and not a theologian. Theological arguments are based on scriptural pronouncements, historical arguments on documents. I feel comfortable around documents and am distrustful of scriptures… are enough to support his claim that he writes with his eye on ordinary readers. This is not to be condemned either. Hagiographical accounts on the Mother and Sri Aurobindo are far too many, and many authors get away simply because they are devotees and do not “require” to gather the testimony of history nor any documentary evidence nor do they need to do any research, but simply draw on belief and faith.

The Mother herself draws heavily on her western ecumenical language even after living for close to half a century in south India and interacting with several like-minded devotees of Sri Aurobindo. Her diary entries are notably filled with her prayers and meditations on the Lord. Even when she records that she once received a communication from Sakyamuni Buddha, she notes: “Learn to radiate and do not fear the storm: the wind carries us far from the shore but shows us the world. Would you be thrifty of tenderness? But the source of love is infinite…” (See p 117) However, despite being born and brought up in the west, she is extremely sensitive to and insightful of the nature of thinking as an Indian.

Quite early in life, she has written (which was published several years later under the title “Myself and My Creed”)

I belong to no nation, no civilization, no society, no race, but to the Divine.

I obey no master, no ruler, no law, no social convention, but the Divine… (see p 131)

Her spiritual knowledge was predominantly practical in its nature, and this probably helped her create and maintain the establishment of the Ashram and later the founding of Auroville, the Universal Township. (144) running the kitchen, the carpentry workshop, garage, gardens accounting office and so forth.

One must be able to act without any preference, free from all attractions and likings , basing oneself solely on the Truth that guides. This, as Hees puts it, is a tenet of many religious writings, “for example the Bhagavad Gita, but the Mother presented it as a matter of psychological observation and practice rather than a doctrine.” (p210)

The responses of political and cultural leaders like Jawaharlal Nehru, or KM Munshi to the Mother while they visited the Ashram are interesting. “…a tennis-playing lady of seventy-five, carrying a tenuous veil and saluting the Ashramites at the march march day after day was not exactly a symbol of spirituality to the normal Indian mind”. (K M Munshi quoted in p,215) Nehru wrote to Indira about the Mother: “The lady has grown quite old and looks fragile… she produced no great impression of spirituality on me.” (quoted p 221) One can remember that she might have appeared politically and academically a naiveté but her inner psychic experiences worked in tandem with one of the greatest rishis of the modern world. At one point Heehs notes that when once some participants of her yoga meeting raised questions on the various facets of yoga, of occult powers, meditation, divine and hostile beings on earth, death and spiritual life, the Mother replied to all these in simple straightforward language, avoiding the obscurity of the Cosmic teachings (that she was exposed to in her early life) and the technical yogic idiom of some of Sri Aurobindo’s works. (see p 165) It is also worth noting that at no time did she or Sri Aurobindo make any public declarations about their spiritual status. On the other hand, they did not object when people treated them as avatars. (p166)

When once she had some mysterious experiences which led her on to miraculous states of existence, she went and reported to Sri Aurobindo. He replied: “All this is very interesting, very well done. You will perform miracles that will make you famous throughout the world.” But he added, this “is not the success we want… One must know how to renounce immediate success in order to create the new world, the supramental world in all its completeness.” Sri Aurobindo and the Mother did not think the supramental transformation was meant only for them and a handful of disciples. It was a step on the way to a general transformation of life on earth.

In her own life Mira Alfassa was never completely alone. Her father was there with her when she was growing up as a support and eventually she married the successful portrait painter Henri Georges Morisset. She had been continuously living a happy life as an artist. However, looking back on her artistic life more than fifty years later she remarked: “I was a perfectly ordinary artist.” She never tried to compare herself with other painters in her circle in terms of technical ability. An increasing understanding of the workings of the consciousness was mattered to her. (see p 45) During the next phase of her life she was deeply involved with esoteric practices of Max Theon, who led her on to planes of experience like cosmic consciousness. What Max Theon gave her came from those written works published in the Revue Cosmique and Tradition Cosmique, and the oral teachings of practical occultism. Mirra absorbed all these and other traditions such as Neoplatonism, Gnosticism, Hermeticism and Kabbalah. These were later incorporated into her own metaphysical synthesis. Eventually she was legally divorced from Henri. That was the time when Paul Richard the intellectual entered her life. It was with Paul that she travelled to Pondicherry, which would become her domicile for the remaining part of her life. Paul had written that his life with Mirra was one of harmony on every level of work., thoughts and feelings. (p 91) It was he who helped the founding of the journal “Arya” in which Sri Aurobindo serialized all his major writings.

Mirra told Paul Richard before they got married that she had gone beyond sex and wanted nothing more to do with it. When Mirra and Sri Aurobindo began their practice of yoga together their relationship was free from sexual intimacy, but it was, in a different way, a union of masculine and feminine elements. (see p 145) During the last months of 1926, as Hees records, most people in the community began to refer to Aurobindo Ghose as Sri Aurobindo and to Mirra as the Mother. Virtually no one in the Ashram circles doubted that the Mother was Sri Aurobindo’s spiritual successor. As long as he was there, she had said, “nothing unfortunate could happen.” When he died, it was like “falling into a hole.” (p208)

The biographer has been diligent in narrating the Mother’s experiences and inner life as per the records and documents he had access to, however, he has been careful in maintaining a distance from the spiritual life of his subject. Time and again Hees has reminded the readers that his was a historian’s role and no more. Towards that end the biography of a spiritual soul who belonged to nowhere in particular and who was bound by no region, religion or dogma is interesting reading. As I mentioned earlier it would satisfy only those interested in basic facts and dates and that kind in a narrative. The earlier part of the book is filled with material facts which may not find any connection with the life of a mystic who was also a radical and practical thinker exploring the self at every point in her life. Before closing this brief assessment of the book, I would like to highlight the fact that Mirra’s primary interest was not “feminine thought” but the process of thought in general. (p42)

During one of her travels Mirra records the conversation with a priest who was travelling overseas “to China to convert the heathens” This was simply more than what she could handle. “Listen,” she said, “even before your religion was born—not even two thousand years ago—the Chinese had a very high philosophy and a path leading them to the Divine, and when they think of Westerners, they think of them as barbarians. Are you going there to convert people who know more about it than you?” (94-95)

Hees in this book distinguishes four overlapping movements in the spiritual development of the Mother: psychic, occult, cosmic and physical. From her childhood she had visions and inner experiences, culminating in what she called an identification with her psychic being. Later she learned how to move through occult planes and to view the saga of the world as a clash between occult beings and forces. After meeting Sri Aurobindo she reconceived this conflict as an evolution of cosmic beings and powers, leading ultimately to the emergence of what Sri Aurobindo called the supermind. The culmination of this movement, she said, would be the descent of the supermind into her physical body and into the ‘earth consciousness’. (263) According to Hees, no one except Sri Aurobindo and the Mother were aware of the action of what they called the supermind. To end on a positive note, as Hees sees it, “the structure and procedures the Mother implemented during her lifetime have endured. Five decades after her passing, the ashram remains a model of effective institutional functioning.” The ashram’s orderliness was particularly striking to Indians because, as Sri Aurobindo once remarked, “India is among the countries in which organized work is successfully done.” (p263)

Peter Heeh’s biography of the Mother is rich in terms of the facts and dates and carries details from documents available in English as well as French. It is eminently readable. Whether it would satisfy the ardent devotees or those readers in search of hidden mystical layers of meaning of a life lived to the full remains to be seen.

Disclaimer from one of Sri Aurobindo’s letters to his disciples: “The tendency to take what I lay down for one and apply it without discrimination to another is responsible for much misunderstanding. A general statement too, true in itself, cannot be applied to everyone alike or applied now and immediately without consideration of condition or circumstance or person or time…” from Sri Aurobindo, The Mother.

Dr.Murali Sivaramakrishnan, Professor and former Chair, Department of English, Pondicherry University