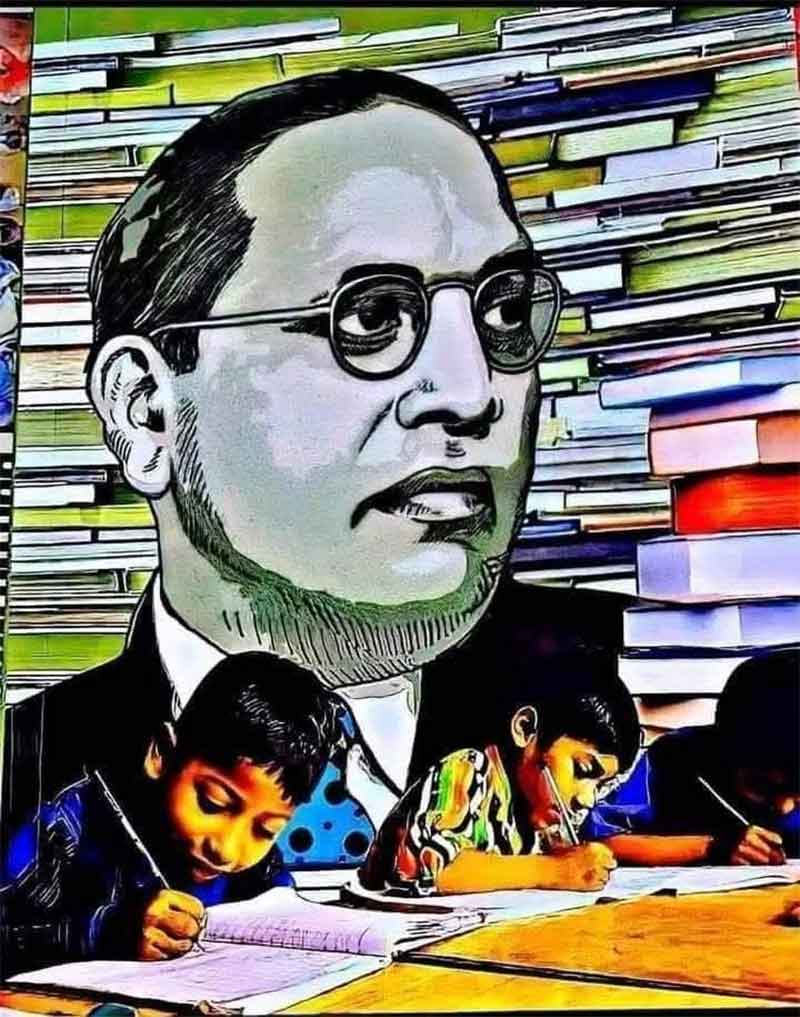

Imagining the shape of India’s Constitution if B.R. Ambedkar had a completely free hand is a speculative exercise, but it can be grounded in his writings, speeches, and actions—revealing a vision far more radical than the document adopted on January 26, 1950. Ambedkar’s worldview, as of April 07, 2025, is well-documented in works like *Annihilation of Caste* (1936), *States and Minorities* (1947), and his Constituent Assembly interventions. Unconstrained by Congress dominance, Gandhi’s influence, or the urgency of post-Partition India, he would likely have crafted a constitution emphasizing social revolution, economic egalitarianism, and a decisive break from caste and religious orthodoxy. Here is how it might have looked:

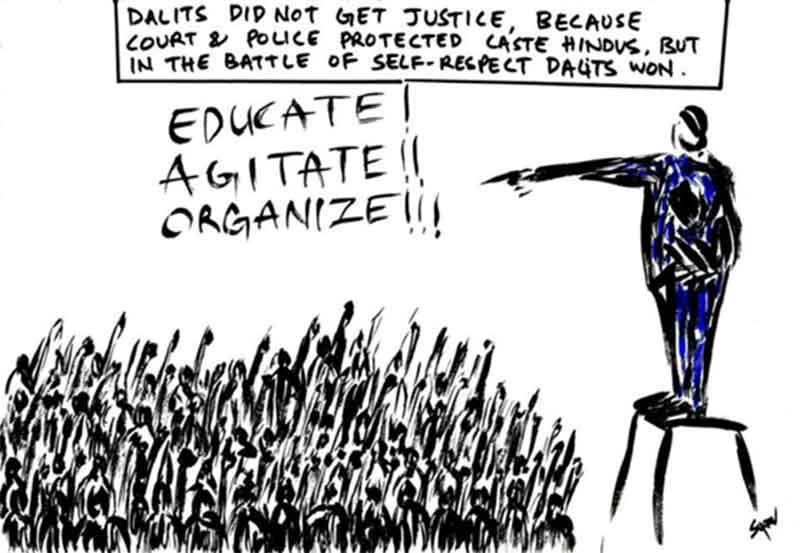

1. Radical Social Justice and Caste Abolition

Ambedkar’s core mission was eradicating caste. With a free hand:

– Explicit Caste Dissolution: Beyond Article 17 (abolishing untouchability), he might have mandated the dissolution of caste as a legal and social category, outlawing endogamy, and caste-based occupations. His 1936 call for “annihilation of caste” suggests laws penalizing caste identification in public life.

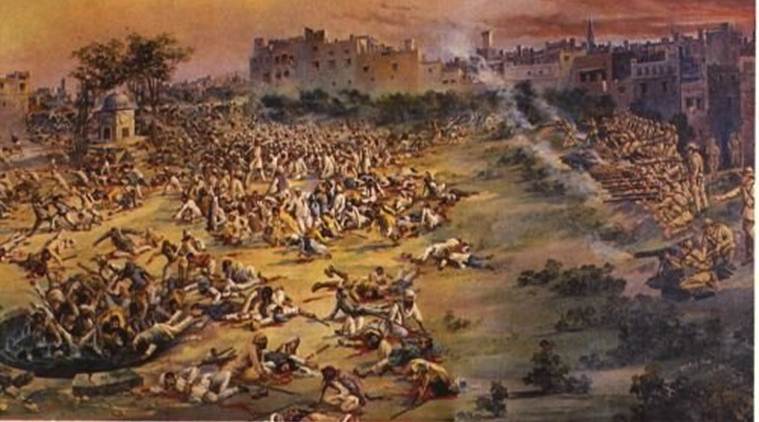

– Separate Electorates for Dalits: He initially favoured separate electorates for Scheduled Castes (SCs), as proposed in the 1932 Communal Award, to ensure political autonomy. Without the Poona Pact’s compromise (reservations within a joint electorate), he might have enshrined this, giving Dalits distinct representation free from upper-caste influence.

– Land Redistribution: In *States and Minorities*, he advocated redistributing land from upper-caste landlords to landless Dalits and peasants, addressing caste-based economic disparities. This could have been a fundamental right, not a mere Directive Principle.

2. Economic Socialism

Ambedkar’s socialism, influenced by Fabianism and his Columbia University training, would have transformed the Constitution’s economic framework:

– State Ownership: He proposed nationalizing key industries and agriculture in *States and Minorities*, arguing for a “state socialism” model. Articles might have mandated government control over land, banks, and major enterprises, enforceable in courts, unlike the diluted Directive Principles (e.g., Article 39).

– Wealth Caps: He might have capped private wealth and inheritance to prevent inequality, a step beyond the vague “equitable distribution” in Article 39(b)–(c).

– Worker Rights: Stronger labour protections—guaranteed wages, union rights, and state employment for the marginalized—could have been fundamental rights, reflecting his belief that economic democracy was prerequisite to political democracy.

3. Uniform Civil Code and Secularism

Ambedkar’s disdain for religious orthodoxy would have driven a bolder secular agenda:

– Mandatory Uniform Civil Code: He strongly supported a uniform civil code (Article 44 is only aspirational in the current Constitution). With full control, he might have abolished personal laws outright—Hindu, Muslim, or otherwise—imposing a secular code for marriage, divorce, and inheritance, prioritizing gender and individual equality over religious tradition.

– Separation of Religion and State: While the adopted Constitution is secular in practice, Ambedkar might have explicitly barred religious influence in governance, education, and public funding, aligning with his critique of Hinduism’s caste underpinnings and his later Buddhist conversion.

4. Decentralized yet Strong Governance

Ambedkar’s federal vision balanced unity with local empowerment, but his free hand would tilt differently:

– Strong Centre with Limits: He favoured a unitary bias to prevent India’s disintegration (a fear post-Partition), but might have avoided the current Constitution’s heavy centralization (e.g., Article 356, President’s Rule). Instead, he could have empowered states with fiscal autonomy while retaining Union supremacy in emergencies.

– Village Rejection: Unlike Gandhi’s panchayat ideal (Article 40), Ambedkar saw villages as “sink[s] of localism” and caste oppression (*Constituent Assembly Debates*, November 4, 1948). He might have excluded rural self-governance, favouring urban-centric administration to modernize society.

5. Enhanced Fundamental Rights

Ambedkar’s rights framework would have been more expansive:

– Right to Employment: Beyond equality (Article 14) and non-discrimination (Article 15), he might have included a justiciable right to work and education for all, especially the marginalized, as a check against economic exclusion.

– Minority Protections: In *States and Minorities*, he proposed safeguards for all minorities—religious, linguistic, and caste-based—including veto powers over discriminatory laws. This could have replaced the weaker Article 30 with enforceable quotas and autonomy.

– Gender Equality: His Hindu Code Bill passion suggests stronger constitutional guarantees for women’s property and marital rights, potentially embedding feminist principles across communities.

6. Judicial and Administrative Reforms

Ambedkar valued institutions but distrusted unchecked power:

– Independent Judiciary: He might have strengthened judicial autonomy beyond Article 50, insulating courts from executive influence with fixed funding and appointments free of political control.

– Administrative Accountability: He could have mandated anti-corruption bodies and citizen oversight of bureaucracy, reflecting his distrust of entrenched elites.

7. Buddhist Influence

Though he converted to Buddhism in 1956, post-Constitution, an unconstrained Ambedkar might have infused its egalitarian ethos earlier:

– Ethical Foundations: The Constitution’s preamble might have cited Buddhist principles—equality, compassion, rationality—over the adopted “secular, socialist” framing added in 1976.

– Education Focus: He saw education as liberation (a Buddhist tenet); compulsory, state-funded education could have been a fundamental right, not a 2002 amendment (Article 21A).

Constraints Avoided

Without Congress moderation, Gandhi’s ruralism, or Assembly debates (7,635 amendments whittled his draft), Ambedkar would have faced no pushback from conservative Hindus resisting personal law reforms, Muslims guarding sharia, or capitalists opposing socialism. The urgency of 1947–1950—Partition, integration of princely states—would not have forced pragmatic concessions like retaining colonial laws (e.g., Indian Penal Code).

Likely Shape

This hypothetical Constitution would have been shorter, sharper, and revolutionary:

– Length: Perhaps 150 articles (vs. 395), focusing on enforceable rights and duties, not procedural minutiae.

– Tone: Militantly egalitarian, with less deference to tradition or gradualism.

– Structure: A socialist, secular republic with a strong Union, no caste or religious privileges, and decentralized power rooted in urban modernity.

Feasibility and Critique

Such a document might have unified India’s downtrodden but alienated elites, risking implementation challenges or civil unrest. Scholars like Granville Austin note Ambedkar’s pragmatism in the real process—balancing ideals with consensus—suggesting he knew a radical draft would not survive 1940s India. His November 25, 1949, speech warned that constitutional machinery depends on societal will; his free-hand vision might have outpaced India’s readiness, delaying adoption or sparking resistance.

Conclusion

If Ambedkar had a free hand, India’s Constitution would have been a bold manifesto of social and economic justice—dismantling caste, enforcing socialism, and secularizing law with a modern, urban bent. It would reflect his dream of a casteless, classless society, but its ambition might have tested India’s fragile post-independence unity. The actual Constitution, tempered by collaboration, traded some of this vision for stability—a compromise Ambedkar accepted but never fully embraced.

SR Darapuri, National President, All India peoples Front

Courtesy: Grok 3