Hugh Fitzgerald is a frequent contributor to Jihad Watch, a website focused on Islamic extremism, where he has served as Vice President on the board since 2004, according to the site’s own listings. However, questions persist about discrepancies in documentation: The David Horowitz Freedom Center’s 990 tax return neither lists him as Vice President nor acknowledges any salary payments to him, as highlighted by Sheila Musaji in her article “Hugh Fitzgerald’s ‘Supermarket Tabloid’ Islamophobia is Showing” in The American Muslim. (1)

Fitzgerald’s writings have drawn criticism for their inflammatory claims about Islam, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic. He argued that Islam discourages adherents from modifying behaviour to reduce viral transmission, suggesting Muslims might view the virus as divine punishment, thereby undermining compliance with public health guidelines. These assertions, reported by the Anti-Defamation League (ADL) in “Islamophobes React to Coronavirus Pandemic with Anti-Muslim Bigotry,” align with far-right narratives and have been widely condemned as Islamophobic. (2)

Speculation about Fitzgerald’s identity includes theories that he is a pseudonym for Robert Spencer, a leading figure in the counter-jihad movement, as explored in the article “Who is Hugh Fitzgerald?” (3) His work has also been linked to extremist ideologies, notably through Anders Behring Breivik, the Norwegian far-right terrorist, who cited Fitzgerald’s writings 18 times in his manifesto “2083: A European Declaration of Independence.” Breivik, notorious for his pro-Nazi, pro-Zionist, and pro-Hindutva stances, misappropriated Fitzgerald’s arguments to frame taqiyya (a concept rooted in Shia theology) as a Sunni tactic of “deception” central to the “Islamization of Europe.” (4)

Breivik’s manifesto quotes Fitzgerald’s claim that “a whole class of people has gotten rich from Arab money and bribes; lawyers, public relations men, and diplomats, journalists, university teachers, and assorted officials” (5)—a trope echoing classic anti-Semitic conspiracy theories redirected at Muslims. Fitzgerald’s rhetoric extends to advocating societal exclusion of Muslims:

“…not only should migration be stopped, but life can be made more difficult… we, as private citizens, do not have to hire Moslems, we do not have to buy their goods… Even the innocent ones, merely by being here, swell Moslem political power.” (6)

Recently, Fitzgerald proposed Ayaan Hirsi Ali as U.S. Ambassador to the UN, praising her ability to confront Muslim representatives with “Quranic verses”:

“At the UN, she would be the Muslim ambassadors’ nightmare. Imagine her quoting from the Qur’an in the General Assembly, noting the verse proclaiming that Muslims are “the best of peoples” (3:110) and non-Muslims are “the most vile of created beings” (98:6). Or think of her quoting the verses instructing Muslims to “strike at the necks” of the unbelievers (47:4) and several dozen other Quranic passages of similar homicidal import.” (7)

Contextualizing Quranic Teachings

Such cherry-picked citations ignore Islam’s ethical core, which emphasizes universal dignity, justice, and compassion. Q.98:6 describes certain individuals as “the vilest of created beings.” This phrase specifically targets those who reject divine truth despite clear evidence, rather than condemning all non-Muslims. The critique is aimed at moral obstinacy, not mere disbelief. Classical scholars like Al-Tabari and Ibn Kathir emphasize that this verse is directed at individuals who actively oppose truth and justice, rather than entire faith communities. The Quran makes distinctions between disbelief and moral corruption, acknowledging righteous non-Muslims and defending places of worship across faiths, as seen in verses 3:113-115, 5:82, and 22:40. This highlights the importance of understanding context in interpreting Quranic verses.

The Quran’s verse 3:110 designates Muslims as “the best of peoples” not through inherent superiority, but as a community tasked with enjoining justice—a mission open to all humanity. The Quran explicitly prioritizes peace (2:190; 8:61), forbids compulsion in religion (2:256), and elevates the sanctity of life (5:32).

Quran 47:4 discusses rules of engagement during defensive warfare, instructing Muslims to “strike at the necks” of disbelievers in battle. However, this command is part of a broader passage that outlines the conduct of warfare, emphasizing the importance of subduing enemies, binding them firmly, and then releasing them through ransom or grace once the war has ended. This verse is specifically related to battlefield ethics, applying only to combatants and not civilians or non-combatants. The Quran prohibits aggression and advocates for peace if the enemy seeks it, as seen in verses 2:190 and 8:61. Historical precedent, such as the Prophet Muhammad’s prohibition on harming non-combatants, and Islamic law (fiqh) also regulate warfare, emphasizing proportionality and minimizing harm. Modern scholars like Dr. Jonathan Brown contextualizes such verses within 7th-century Arabian tribal conflicts, highlighting the importance of understanding their historical context.

The Quran promotes coexistence, instructing Muslims to deal kindly and fairly with those who have not fought them (60:8).

When interpreting these verses, holistic interpretation, Maqasid al-Shariah (higher objectives), and progressive revelation are essential principles. These principles prioritize peace, preservation of life, faith, intellect, lineage, and property, and emphasize forgiveness and asylum for non-combatants.

Ultimately, the Quran’s teachings, when read in context, reject blanket hostility toward non-Muslims and instead provide guidelines for self-defence in extreme circumstances. This understanding is rooted in the Quran’s universal values of justice, mercy, and human dignity, as stated in 17:70, “We have honoured the children of Adam” – a dignity extended to all humanity, regardless of faith.

Key principles refuting Fitzgerald’s narrative include:

• Universal Human Dignity: “We have honoured the children of Adam” (17:70).

• Justice Beyond Tribalism: “Stand firm in justice, even against yourselves or your kin” (4:135).

• Interfaith Respect: “Do not insult those they invoke besides God” (6:108).

• Mercy as Covenant: “Show mercy to those on Earth, and the One above the heavens will show mercy to you” (Tirmidhi 1924).

Islam’s legacy is one of pluralism (30:22) and dialogue (16:125). Reducing it to decontextualized verses ignores its call for ethical reflection (tadabbur) and its vision of a just world. Muslim scholars and leaders actively counter extremism through interfaith partnerships and human rights advocacy, embodying Quranic ideals of coexistence.

Ayaan Hirsi Ali has drawn both acclaim and condemnation for her characterization of Islam as “a destructive, nihilistic cult of death,” a stance critics argue conflates extremism with the faith’s 1.9 billion adherents. Organizations such as the Southern Poverty Law Center have denounced her “anti-Muslim rhetoric” as “remarkably toxic,” while scholars and interfaith advocates warn that her framing risks exacerbating Islamophobia rather than fostering dialogue.

While Hirsi Ali’s critiques stem from her lived trauma under authoritarian regimes, her blanket condemnations of Islamic theology stand in stark contrast to the nuanced work of Muslim reformers and counter-extremism experts who distinguish between faith and violence. Nominating her to a diplomatic position tasked with bridging global divides would signal a confrontational approach to Muslim-majority nations at a time when multilateral cooperation is critical. Ultimately, Hirsi Ali’s potential nomination demands careful scrutiny: Would her platform advance human rights and religious freedom, or deepen polarization? The answer hinges on balancing principled criticism of extremism with the diplomatic imperative to build inclusive alliances—a challenge central to combating Islamophobia without alienating Muslim communities worldwide.

Bibliography

1. Sheila Musaji, Hugh Fitzgerald’s ‘Supermarket Tabloid’ Islamophobia is Showing, The American Muslim February 19, 2008

2. https://www.adl.org/resources/article/islamophobes-react-coronavirus-pandemic-anti-muslim-bigotry

3. Anders Behring Breivik, “2083: A European Declaration of Independence” https://www.rai.it/dl/docs/13115255886322083-A-European-Declaration-of-Independence.pdf

4. Sindre Bangstad, Anders Breivik and the Rise of Islamophobia, London, Zed Books, 2014, p.233

5. Unni Turrettini, The Mystery of the Lone Wolf Killer: Anders Behring Breivik and the Threat of Terror in Plain Sight, Pegasus Books, 2015, p.76)

6. https://www.islamophobiawatch.co.uk/watching-jihad-watch/

7. Hugh Fitzgerald, Who Should Be Our Ambassador to the UN? Jihad Watch, April 3, 2025

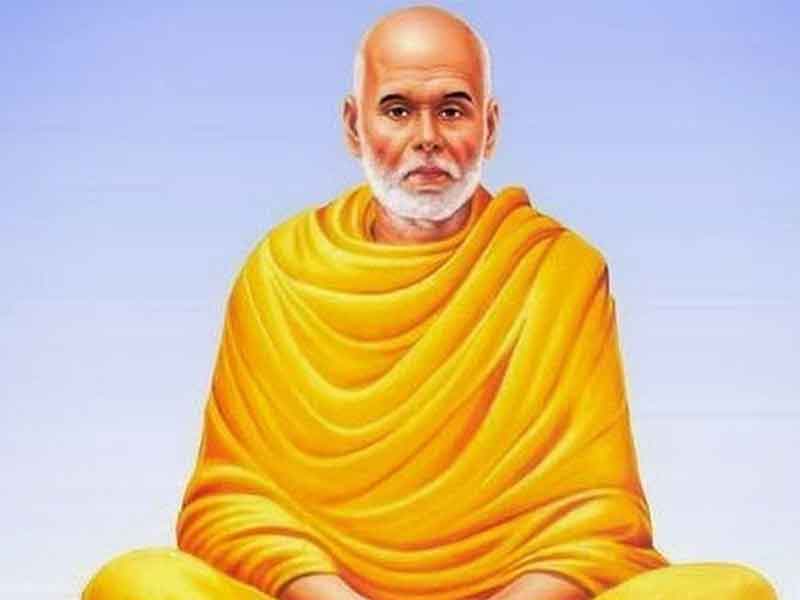

V.A. Mohamad Ashrof is an independent Indian scholar specializing in Islamic humanism. With a deep commitment to advancing Quranic hermeneutics that prioritize human well-being, peace, and progress, his work aims to foster a just society, encourage critical thinking, and promote inclusive discourse and peaceful coexistence. He is dedicated to creating pathways for meaningful social change and intellectual growth through his scholarship. He can be reached at [email protected]