In an era marked by rising injustice, hate-driven ideologies, and ecological crises, the need for solidarity across religious lines has never been more critical. The Abrahamic faiths—Islam, Christianity, and Judaism—share a common call for cooperation in righteousness and against oppression. This paper explores a framework for interfaith solidarity rooted in Quranic teachings, particularly Q.5:2 and 8:73, and examines how these principles resonate with Biblical teachings and modern interfaith initiatives. By integrating theological insights with scientific research on the effectiveness of interfaith dialogue, this paper aims to present a comprehensive case for why and how people of different faiths can and should unite against oppression.

Theological Foundations: Interpreting Quranic and Biblical Texts

The Quranic verses 5:2 and 8:73 provide a theological foundation for interfaith cooperation against oppression. Q. 5:2, “Cooperate in righteousness and piety, but do not cooperate in sin and aggression,” establishes a clear ethical boundary for cooperation: it must be grounded in moral good (birr) and God-consciousness (taqwa). This principle is not confined to intra-faith relations but can be extended to include all who uphold justice and compassion, making it a basis for interfaith collaboration.

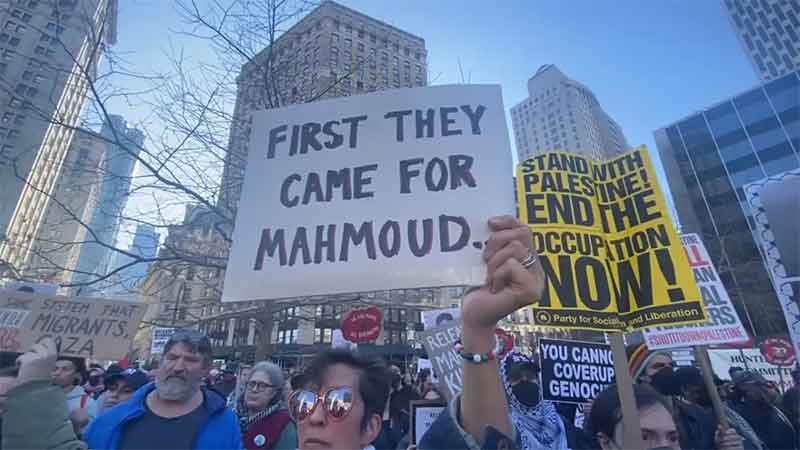

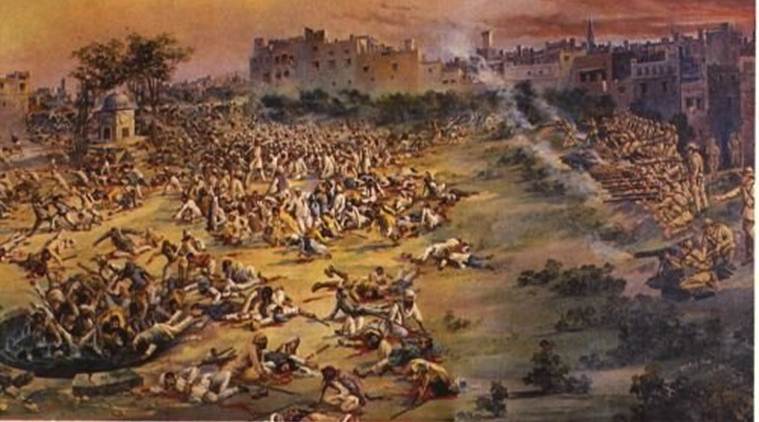

Q.8:73 adds a strategic dimension: “Those who disbelieve are allies of one another. If you do not [cooperate and ally with each other], there will be fitnah (persecution) on earth and great corruption.” In a modern context, “those who disbelieve” can be understood as forces of oppression and corruption, while “the believers” include all people of faith who strive for justice and peace, thus justifying interfaith cooperation against networked oppression.

Biblical teachings echo this sentiment. Galatians 6:2, “Carry each other’s burdens,” and Proverbs 11:14, “For lack of guidance a nation falls, but victory is won through many advisers,” highlight shared responsibility and the strength of unity, aligning with Quranic principles. Micah 6:8, “Act justly, love mercy, walk humbly,” and Romans 12:21, “Overcome evil with good,” further complement this, emphasizing collective resistance against exploitation. These parallels reveal a shared moral horizon that transcends religious differences, fostering a basis for Abrahamic cooperation.

Strategic Unity Against Global Corruption: Lessons from Quran 8:73

Quran 8:73 warns that disunity among the righteous enables fitnah (moral disorder) and fasad kabir (widespread corruption). While originally addressing intra-Muslim solidarity, its logic applies globally. In an interconnected world facing authoritarianism, climate collapse, and systemic inequality, fragmented moral voices risk enabling harm. The verse thus calls for strategic alliances among faith communities—Muslims, Christians, Jews, and others—to counter networked oppression. This aligns with Romans 12:21’s call to “overcome evil with good,” emphasizing collective resistance against exploitation.

Interfaith Resonance: Biblical Parallels

The Quranic mandate for cooperation finds resonance in Biblical teachings:

• Galatians 6:2 (“Carry each other’s burdens”) mirrors the Quranic emphasis on shared responsibility.

• Proverbs 11:14 (“Victory is won through many advisers”) underscores the strength of unity.

• Micah 6:8 (“Act justly, love mercy, walk humbly”) and Quran 49:13 (“O mankind, We created you to know one another”) both champion inclusive citizenship.

Such parallels reveal a shared moral horizon, enabling faith communities to transcend divisions through joint action.

Farid Esack’s Vision of Interfaith Solidarity

Farid Esack, a South African Muslim scholar, writer, and activist, is renowned for his progressive interpretations of Islam and tireless advocacy for social justice, human rights, and interfaith dialogue, with a particular emphasis on fostering interfaith solidarity against systemic oppression.

Farid Esack’s vision of interfaith solidarity is rooted in his understanding of the Quranic concept of “ummah,” or the global community of believers. For Esack, this concept extends beyond the Muslim community to encompass all people of faith who are committed to justice, compassion, and human dignity. He argues that the struggles faced by one faith community are, in fact, struggles faced by all, and that people of different faiths must come together to address issues like poverty, inequality, and violence.

Esack’s approach to interfaith solidarity is distinct from more superficial forms of interfaith dialogue, which often focus on platitudes and shared values. Instead, he emphasizes the importance of engaging with the particularities of each faith tradition, including their unique histories, practices, and theological perspectives. By doing so, Esack believes that people of different faiths can develop a deeper understanding of one another and build more meaningful relationships. This approach also allows for a more nuanced exploration of the ways in which different faith traditions intersect and overlap, particularly in their responses to social and economic injustices.

Through his work, Esack has sought to put his vision of interfaith solidarity into practice, partnering with faith leaders and organizations from around the world to address pressing social and economic issues. He has worked extensively on issues like HIV/AIDS, poverty, and human rights, using his platform to amplify the voices of marginalized communities and challenge systems of oppression. By emphasizing the importance of collective action and mutual support, Esack’s vision of interfaith solidarity offers a powerful framework for building a more just and compassionate world:

“The Quran, in my view, is not a document that merely demands obedience; it is a text that invites struggle—struggle with oneself, with society, and with the text itself in the pursuit of justice.” (Esack, p. 12) “Pluralism is not about diluting one’s faith to accommodate others; it is about recognizing that the divine truth is too vast to be confined to a single tradition, and justice demands we walk together.” (Esack, p. 146) “To read the Quran in the context of oppression is to hear its cry for the marginalized, to see its verses not as static rules but as a dynamic call to resist injustice alongside all who suffer.” (Esack, p. 82)

This vision of interconnectedness and interdependence is not new, and has been foreseen by seers and philosophers for decades. The pacifist scholar-activist Martin Luther King Jr. eloquently captured this idea when he said, “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere. We are intertwined in an inescapable web of interdependence, bound together like threads in a single tapestry of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects us all indirectly.” (King Jr., p. 2-3) These words, penned over six decades ago, remain profoundly relevant today, as we continue to grapple with the complexities of global interconnectivity and the pursuit of justice.

Practical Applications: Building Bridges and Countering Hate

1. Climate Justice Movements: Interfaith coalitions, such as the Islamic-Christian-Jewish environmental stewardship networks, operationalize birr and taqwa by addressing ecological crises as a collective moral duty.

2. Humanitarian Coalitions: Faith-based efforts to combat poverty and war draw on Abrahamic teachings of mercy, exemplified by the Al Amana Centre’s dialogue programs in Oman, which foster empathy across religious divides.

3. Countering Extremism: Initiatives like A Common Word leverage shared values to dismantle hate-driven ideologies, aligning with Quran 8:73’s call for coordinated moral resistance.

Toward Inclusive Citizenship and Collective Responsibility

The framework promotes societies where diversity is a strength. Quran 4:135 (“Stand firmly for justice”) and Proverbs 31:8-9 (“Speak for those who cannot”) demand advocacy for marginalized communities. By integrating Quranic and Biblical teachings, interfaith partnerships can shape policies rooted in compassion, such as interfaith community clean-ups or educational programs that bridge religious divides.

Contemporary examples of interfaith cooperation demonstrate how these theological principles can be applied to combat oppression. The “A Common Word Between Us and You” initiative, launched in 2007, brought together Muslim and Christian leaders around the shared principles of loving God and neighbour, demonstrating how theological commonalities can foster peace and understanding A Common Word. Similarly, the Al Amana Centre in Oman facilitates dialogue between different faith communities, promoting coexistence and mutual respect.

In the realm of social justice, interfaith coalitions have been instrumental in advocating for human rights, environmental stewardship, and poverty alleviation. For instance, the Interfaith Centre on Corporate Responsibility brings together religious investors to hold corporations accountable for their social and environmental impacts. These initiatives show how faith-based organizations can collaborate on secular issues, transcending religious boundaries to address systemic oppression, such as climate justice movements and humanitarian coalitions combating poverty and war.

Scientific Perspectives: Empirical Evidence from Social Sciences

Research in social sciences supports the efficacy of interfaith dialogue in reducing prejudice and fostering cooperation. A study by Barnas (2022) on interfaith youth programs, such as Interfaith Philadelphia’s Walking the Walk (WTW) Youth Initiative and Garden State Mobilizing Our Students for Action to Build Interfaith Community (MOSAIC), found that participants developed greater appreciation and tolerance for other faiths, with many engaging in community service projects that addressed religious intolerance (Barnas, 2022). The study interviewed seven alumni aged 20–29, showing they gained confidence from knowledge about other religions, participated in initiatives like co-founding racial justice organizations, and worked with Zones of Peace programs and community gardens to reduce violence and provide fresh food (Barnas, 2022). Recommendations included incorporating comparative religion courses in schools and promoting religious equality via shared projects (Barnas, 2022).

Additionally, studies on contact theory, as proposed by Allport, suggest that positive interactions between members of different groups can reduce intergroup bias (Allport, 1954). Interfaith dialogue provides a structured setting for such interactions, allowing participants to build relationships based on mutual respect and understanding (Allport, 1954). Further research by Hedges (2023) explores how interreligious dialogue can serve as a tool for conflict prevention and reconciliation, highlighting its role in peacebuilding (Hedges, 2023). These findings underscore the practical impact of interfaith cooperation in addressing oppression by fostering trust and collaboration across diverse communities.

World Council of Churches’ Decade to Overcome Violence (2001–2010), which brought together Christian denominations and other faith communities to address violence and promote peace (World Council of Churches, 2010). This initiative highlighted the power of collective action in confronting systemic oppression, aligning with the framework’s call for strategic unity.

A Call to Sacred Solidarity

The “Joint Operation in the Path of Righteousness” framework presents a compelling vision for interfaith collaboration, rooted in Quranic verses 5:2 and 8:73, and echoed in Biblical teachings. This initiative invites Abrahamic faiths to join forces as co-labourers for justice, amplifying their moral impact through unity without diluting their individual religious identities. By embracing this Quranic mandate, faith communities can model a future where shared humanity prevails over division, fostering global peace through collective action.

This framework offers a strategic and sacred approach to addressing pressing global issues, from climate change and social injustice to countering hate and oppression. Scientific research supports the effectiveness of interfaith cooperation in reducing intolerance and building peaceful societies. As the world moves forward, embracing this shared moral horizon can empower faith communities to create a world where diversity is a strength, and collective action overcomes oppression. By working together, people of different faiths can ensure a brighter future, built on the principles of justice, compassion, and unity.

Bibliography

Allport, G. W; The nature of prejudice, Reading, Massachusetts: Addison-Wesley, 1954

Barnas, T. J, The effectiveness of interfaith dialogue in countering religious intolerance: A phenomenological study of interfaith youth program alumni (Doctoral dissertation, New Jersey City University), 2022

Esack, Farid, Quran, liberation and pluralism: An Islamic perspective of interreligious solidarity against oppression. Oxford: Oneworld, 1997

King Jr, Martin Luther, Letter from Birmingham Jail, Harmondsworth: Penguin Random, 1964

World Council of Churches, Decade to Overcome Violence, 2001–2010: Final report, Geneva: WCC, 2011

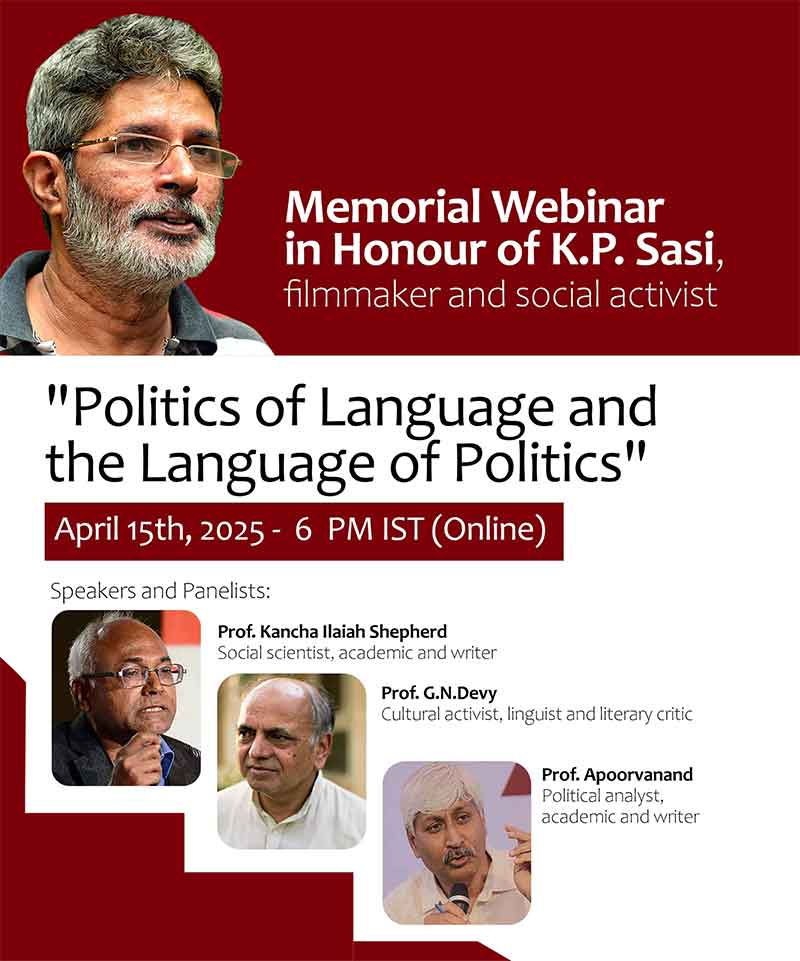

V.A. Mohamad Ashrof is an independent Indian scholar specializing in Islamic humanism. With a deep commitment to advancing Quranic hermeneutics that prioritize human well-being, peace, and progress, his work aims to foster a just society, encourage critical thinking, and promote inclusive discourse and peaceful coexistence. He is dedicated to creating pathways for meaningful social change and intellectual growth through his scholarship. He can be reached at [email protected]