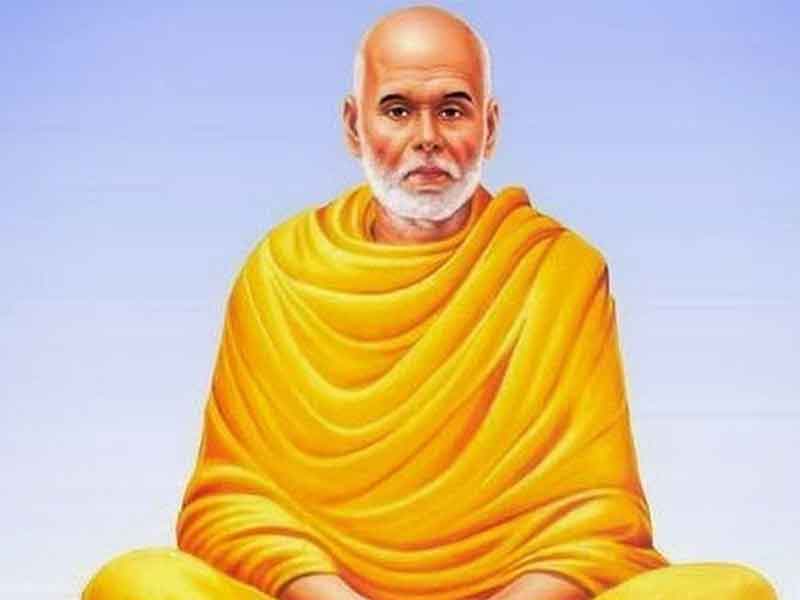

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the princely state of Travancore in Kerala, South India, was a society languishing in the throes of a deeply entrenched and brutal caste system. The social fabric was so pathologically fragmented by oppressive customs of untouchability, unapproachability, and un-seeability that Swami Vivekananda, upon witnessing it, famously described the region as a “lunatic asylum.” It was into this crucible of profound human degradation and structural violence that Sree Narayana Guru (1856-1928) emerged, not merely as a sage or a religious figure, but as the principal architect of a sweeping socio-spiritual renaissance. His life and teachings constituted a radical departure from the ossified religious traditions of his time. This paper argues that Sree Narayana Guru’s philosophy was not simply a reformation of Hinduism but a revolutionary humanistic project aimed at achieving universal prosperity. He achieved this by forging a powerful synthesis of Advaita Vedanta’s metaphysical non-duality, pragmatic social action, and a rational, inclusive approach to spirituality, thereby creating a timeless blueprint for holistic human development that transcends sectarian divides. By examining the historical context of his mission, the philosophical depth of his teachings, the practical genius of his institutional frameworks like the Sivagiri Pilgrimage and the Aluva Interreligious Conference, and the enduring relevance of his message, we can appreciate his vision as a comprehensive pathway toward a just, enlightened, and prosperous global community.

The Crucible of Reform – Kerala’s Socio-Religious Milieu

To comprehend the revolutionary import of Sree Narayana Guru’s message, one must first understand the darkness he sought to dispel. The caste system in pre-modern Kerala was arguably the most rigid and dehumanizing in all of India. Society was bifurcated into the savarnas (caste Hindus) and the avarnas (those outside the caste hierarchy), who constituted the majority of the population. The avarnas, including communities like the Ezhavas (the Guru’s own community), Pulayas, and Parayas, were subjected to a litany of prohibitions designed to enforce their subjugation. They were denied access to public roads, wells, markets, and government schools. Their right to education was non-existent, and they were forbidden from entering temples consecrated by the Brahmanical order.

The historian Robin Jeffrey, in his seminal work The Decline of Nayar Dominance, meticulously documents the socio-political landscape of Travancore, where caste purity laws dictated every facet of life. The concept of theendal (pollution by distance) was enforced with mathematical cruelty; an Ezhava was expected to maintain a distance of thirty-six feet from a Nambudiri Brahmin, while a Pulaya had to keep ninety-six feet away. (Jeffrey, p. 23) The penalties for transgression were often violent. This system was not merely a social hierarchy; it was a form of spiritual and psychological warfare that stripped individuals of their basic dignity and personhood. The avarnas were denied not only material resources but also the very right to a dignified human identity.

It was against this backdrop of systemic oppression that Sree Narayana Guru began his silent revolution. His first major public act, the consecration of a Shiva idol at Aruvippuram in 1888, was a seismic event. When questioned by orthodox Brahmins about his authority to perform a consecration—a right reserved for them—his calm and profound reply, “I have consecrated not a Brahmin Shiva, but an Ezhava Shiva,” shattered centuries of religious monopoly. This act was a declaration of spiritual independence. It asserted that the divine was not the exclusive property of any caste and that every human being possessed the inherent right to access it. As sociologist M.S.A. Rao notes, this single act “symbolized the new legitimation for the cultural and religious rights of the lower castes” and marked the beginning of a powerful social movement aimed at self-respect and emancipation. (Rao, p. 112) The Aruvippuram consecration was not just a ritual; it was a philosophical statement that laid the groundwork for his entire life’s mission: to reclaim human dignity from the clutches of religious dogma.

The Philosophical Bedrock – Advaita Vedanta Reimagined as Social Praxis

At the core of Sree Narayana Guru’s revolutionary thought lies his radical reinterpretation of Advaita Vedanta, the non-dualistic philosophy most famously systematized by Adi Shankaracharya. Traditional Advaita posits the ultimate reality as Brahman—a singular, attributeless, and all-pervading consciousness—and asserts that the individual self, or Atman, is identical to this Brahman. However, in popular practice and even within scholastic circles, Shankara’s Advaita was often interpreted as world-negating (the world is an illusion), encouraging a retreat from worldly affairs in pursuit of individual liberation (moksha).

Sree Narayana Guru, a master of Sanskrit and Tamil scriptures, took this profound metaphysical principle of oneness and turned it outward, transforming it into a potent tool for social transformation. He reasoned with unassailable logic: if the ultimate reality is one, and all beings are manifestations of that same indivisible consciousness, then how can distinctions of caste, creed, or race be anything but a product of ignorance (avidya)? For the Guru, Advaita was not an abstract doctrine for hermits but a living, breathing truth that demanded social application. His disciple and foremost philosophical interpreter, Nataraja Guru, articulated this shift by stating that the Guru’s work was to bring the “Absolute value of the Vedanta from its sterile high regions of abstraction into the workaday world of life.” (Nataraja Guru, p. 198)

This “Practical Advaita” finds its most sublime expression in the Guru’s magnum opus, Atmopadesa Satakam (One Hundred Verses of Self-Instruction). In this work, he dismantles the foundations of social hierarchy using the logic of non-duality. Verse 44 reads:

“The ‘other person’ is the bearer of my own form. Thinking thus, one should do for him what is for one’s own good.”

This verse is a profound ethical injunction derived directly from Advaitic metaphysics. It dissolves the self-other dichotomy and establishes compassion (karuna) not as a mere sentiment but as a rational consequence of understanding reality. If the “other” is an extension of oneself, then harming or degrading another is an act of self-harm. Conversely, working for the upliftment of others is the highest form of self-interest. In another verse, he directly confronts casteism:

“One in kind, one in faith, one in God is man; Of one womb, of one form, difference there is none.” (Atmopadesa Satakam, v. 45)

Here, the Guru establishes the biological and spiritual unity of humankind as an undeniable fact, rendering the man-made divisions of caste philosophically absurd and morally untenable. His philosophy, as scholar S. Omana observes, was a “humanistic Advaita” that sought “the liberation of man in this world and in this life,” emphasizing social harmony and ethical conduct as inseparable from spiritual realization (Omana, p. 154). By democratizing the highest wisdom of the Upanishads and making it a charter for social equality, Sree Narayana Guru transformed a philosophy of transcendence into a powerful engine of immanent justice.

“One Caste, One Religion, One God” – Deconstructing a Revolutionary Edict

The Guru’s most famous aphorism, “Oru Jati, Oru Matham, Oru Daivam Manushyanu” (One Caste, One Religion, One God for Humankind), became the clarion call of the Kerala renaissance. Far from being a simplistic slogan, it is a deeply layered philosophical statement that requires careful deconstruction.

One Caste: This was a direct and frontal assault on the caste system and the myriad sub-caste divisions that had atomized society. The “one caste” he proclaimed was the caste of humanity. He was not calling for the creation of a new, single caste but for the complete annihilation of caste as a social identifier. This principle advocated for the primacy of a shared human identity over all inherited or imposed labels. It was a call for social integration, promoting inter-dining and inter-marriage, practices that were considered grave sins at the time. He later refined this idea, reportedly telling his disciple Sahodaran K. Ayyappan that the time had come to declare, “No Caste, No Religion, No God for man,” a statement pushing his followers towards a purely rational, secular humanism. This evolution demonstrates his dynamic and context-sensitive approach to reform.

One Religion: This is perhaps the most misunderstood aspect of his teaching. The Guru was not advocating for a syncretic world religion or the abolition of existing faiths. Rather, the “one religion” was the universal religion of goodness, or the ethical core that underpins all faiths. His definitive statement, quoted in the initial text, “Whatever be the religion of a man, it is enough if he becomes good,” encapsulates this idea perfectly. He shifted the focus of religion from external conformity—rituals, doctrines, and institutional affiliations—to internal transformation. The goal of any true religion, in his view, is to make an individual a better human being: more compassionate, more just, and wiser. As T. Bhaskaran highlights, the Guru saw religion as a means to an end, not an end in itself. The ultimate aim was “the moral and spiritual elevation of the individual and society,” and any religion that failed to achieve this was, in his view, failing its purpose. (Bhaskaran, p. 91)

One God: The “one God” of Sree Narayana Guru is not the jealous, exclusive deity of certain monotheistic traditions. It is the Advaitic Absolute—the singular, non-dual Reality (Brahman) that is the source, substance, and substratum of all existence. This God is not a being who resides in a distant heaven but is the very consciousness that animates every living thing. It is the unifying truth that can be realized through different paths, whether through devotion (bhakti), knowledge (jnana), or action (karma). By defining God in this inclusive, immanent way, the Guru provided a theological basis for religious pluralism. If all religions are ultimately attempts to apprehend the same infinite Reality, then their quarrels are born of a limited perspective, like the blind men each touching a different part of the elephant and claiming to know the whole animal.

The Sivagiri Pilgrimage – A Blueprint for Integral Humanism

The Guru’s genius lay not only in articulating profound philosophy but also in creating practical frameworks for its realization. The Sivagiri Pilgrimage, conceived by him in 1928, stands as a testament to his vision of “integral humanism”—a holistic approach to development that weds spiritual discipline with socio-economic progress. When his disciples, Vallabhasseri Govindan Vaidyan and T.K. Kittan Writer, proposed a traditional pilgrimage, the Guru redefined its purpose entirely. He envisioned it not as a ritualistic journey for earning spiritual merit, but as a dynamic educational seminar for the masses. He prescribed eight specific goals for the pilgrims to focus on, a framework that can be seen as a modern, socially-oriented version of the Buddha’s Eightfold Path.

1. Education: This was the cornerstone of his reform. For the Guru, education was synonymous with enlightenment. It was the primary tool for eradicating superstition, challenging oppressive dogmas, and fostering critical thinking. He believed that knowledge empowers individuals to reclaim their agency and build a self-reliant community.

2. Cleanliness: This principle extended far beyond mere physical hygiene. It encompassed a tripartite purity: physical cleanliness for public health, mental cleanliness (clarity of thought and freedom from prejudice), and moral cleanliness (ethical conduct in personal and public life). This holistic concept of purity stood in stark contrast to the Brahminical notion of ritual purity based on caste.

3. Devotion to God: In the Guru’s framework, devotion was not about ostentatious rituals or blind faith. It was a path of disciplined self-contemplation, a means of turning inward to recognize the divine spark within oneself. It was about cultivating humility, self-control, and a constant awareness of the ultimate unity of all life.

4. Organization: The Guru understood that individual transformation, while essential, was insufficient to dismantle deeply entrenched structures of oppression. He famously advised, “Organize and be strong; educate and be free.” This pillar emphasized the necessity of collective action, social cohesion, and building strong community institutions to advocate for social, economic, and political rights.

5. Agriculture: This, along with the next three pillars, formed the economic foundation of his vision. He recognized that for a largely agrarian society, economic independence began with the land. He promoted scientific farming methods and stressed the dignity of labour, viewing agriculture as a means of achieving food security and self-reliance.

6. Trade: The Guru encouraged the community to engage in commerce and business, but with a strong ethical foundation. He advocated for fair trade practices, honesty, and creating sustainable economic networks that would benefit the entire community, not just a few individuals.

7. Handicrafts: This pillar aimed to preserve and promote traditional skills and artisanal labour. In an era of increasing industrialization, he saw the value in skilled craftsmanship as a source of livelihood, cultural pride, and economic resilience.

8. Technical Training: Far from being a traditionalist who rejected modernity, the Guru was a pragmatist who urged his followers to embrace science and technology. This pillar underscored the importance of acquiring modern technical skills to adapt to a changing world and to create new opportunities for economic advancement.

The Sivagiri Pilgrimage, with these eight objectives, is a masterclass in social engineering. It transformed a religious practice into a powerful vehicle for mass education and empowerment, demonstrating that true spirituality must be concerned with the total well-being—material, intellectual, and moral—of humanity.

Institutionalizing Pluralism – The Aluva Interreligious Conference

Sree Narayana Guru’s commitment to interfaith harmony found its most concrete expression in the All-Religions Conference he convened at the Aluva Advaita Ashram in 1924. This event was a pioneering effort in the history of global interfaith dialogue, predating many similar initiatives in the West. Its purpose was revolutionary, as declared on the banner at the entrance: “Not for arguing and winning, but for knowing and informing.”

This motto itself is a profound lesson in epistemology and dialogue. It signalled a radical shift away from the polemical, competitive, and often violent history of religious interactions. The Guru was not interested in proving one religion superior to another. Instead, he created a space for “epistemological humility,” where representatives from Hinduism, Christianity, Islam, Buddhism, and other traditions could present the core tenets of their faiths without fear of judgment or debate. The goal was mutual understanding. As Swami Muni Narayana Prasad explains, the Guru believed that “when the essential principles of all religions are understood with a clear mind, it becomes evident that there is no fundamental ground for conflict.” (Muni Narayana Prasad, p. 115)

The Aluva conference institutionalized the Guru’s core belief that truth is not the exclusive monopoly of any single tradition. He famously stated, “Know the truth of all religions and make it known to others; this is the way to peace.” (Kusuman, p. 103) This was not a call for a facile eclecticism but for a deep and impartial study of world religions. He even envisioned a university where different faiths could be studied side-by-side with the same scholarly rigor and respect accorded to the sciences. The conference was a practical demonstration of how religious diversity, when approached with an open mind, could be a source of collective wisdom rather than a cause for perpetual conflict. It remains a powerful model for constructive dialogue in our increasingly polarized world.

Legacy and Contemporary Relevance – A Vision for the 21st Century

In an era marked by rising religious fundamentalism, resurgent ethno-nationalism, and widening economic inequality, Sree Narayana Guru’s humanistic vision is more relevant than ever. His teachings offer a potent antidote to the very poisons that afflict contemporary global society.

First, his emphasis on reason and critical inquiry (viveka) as essential components of faith provides a powerful counter-narrative to blind dogmatism. He encouraged followers to question, to analyse, and to discern the truth for themselves, liberating spirituality from the cages of orthodoxy and literalism.

Second, his model of integral development, as exemplified by the Sivagiri principles, offers a sustainable and holistic alternative to purely materialistic models of progress. He understood that genuine prosperity cannot be measured by GDP alone; it requires educational enlightenment, social justice, ethical governance, and spiritual well-being. This integrated approach is a vital lesson for a world grappling with the social and environmental consequences of unbalanced development.

Third, his unwavering commitment to social equality and the annihilation of caste remains a clarion call for justice in India and beyond. His declaration, “We do not belong to any particular caste or religion,” is a radical affirmation of a universal human identity that must precede all other affiliations. It challenges us to dismantle the myriad structures of prejudice—based on race, gender, sexuality, or nationality—that continue to divide humanity.

Finally, his blueprint for interfaith dialogue based on “knowing and informing” provides a pathway out of the cycle of religious violence. He demonstrated that it is possible to hold deep personal convictions while engaging with others in a spirit of mutual respect and open-ended learning.

Toward a Universal Religious Ethic

Sree Narayana Guru’s life and work represent a profound paradigm shift in the understanding of religion and its role in human society. He masterfully chiseled away the non-essential, ritualistic, and divisive crusts of religion to reveal its luminous, universal core: the elevation of the human spirit toward goodness, wisdom, and unity. His teachings call us to move beyond a religion of identity to a religion of ethics; from a spirituality of exclusion to one of universal brotherhood.

He did not merely preach; he built institutions, crafted philosophies, and lived a life that demonstrated his core message: humanity precedes religion. The ultimate purpose of any spiritual path, he showed, is not to create loyal followers for a particular creed but to nurture compassionate, rational, and liberated human beings. By grounding the sublime metaphysics of Advaita in the soil of social reality, he created a powerful ethic for living that is both spiritually profound and pragmatically effective. In a world fractured by conflict and ideology, the Guru’s vision of “One Caste, One Religion, One God” is not a utopian dream but an urgent and practical necessity. By embracing his inclusive, humanistic, and rational spirit, we can begin to build bridges where others have built walls, and walk together toward a future of universal prosperity, justice, and enlightenment.

Bibliography

Bhaskaran, T. Sree Narayana Guru: A Life of Self-Realisation. Thiruvananthapuram: Kerala Bhasha Institute, 2002

Jeffrey, Robin. The Decline of Nayar Dominance: Society and Politics in Travancore, 1847-1908. New Delhi: Vikas Publishing House, 1976

Kusuman, K.K. Sree Narayana Guru: The Social Philosopher. Thiruvananthapuram: Kerala Historical Society, 1987

Muni Narayana Prasad. The Philosophy of Narayana Guru. New Delhi: D.K. Printworld, 2009

Nataraja Guru. The Word of the Guru: An Outline of the Life and Teachings of Sree Narayana Guru. New Delhi: D.K. Printworld, 2003

Omana, S. The Philosophy of Sree Narayana Guru. Varkala: Narayana Gurukula Foundation, 1984

Rao, M.S.A. Social Movements and Social Transformation: A Study of Two Backward Classes Movements in India. New Delhi: Macmillan, 1979

Sree Narayana Guru. Atmopadesa Satakam (One Hundred Verses of Self-Instruction). Translated by Swami Muni Narayana Prasad. Kollam: Narayana Gurukula, 2007

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest CounterCurrents updates delivered straight to your inbox.

V.A. Mohamad Ashrof is an independent Indian scholar specializing in Islamic humanism. With a deep commitment to advancing Quranic hermeneutics that prioritize human well-being, peace, and progress, his work aims to foster a just society, encourage critical thinking, and promote inclusive discourse and peaceful coexistence. He is dedicated to creating pathways for meaningful social change and intellectual growth through his scholarship. He can be reached at [email protected]