The international legal principle of non-refoulement and India’s obligation under this has come under intense media discussions following India deported on October 4 seven Rohingya immigrants back to their country of origin i.e. Myanmar where they fear persecution. India is also contemplating en mass deportation of around 40,000 Rohingya immigrants living in different parts of the country.

Though the Rohingya have been persistently persecuted in Myanmar for decades, the situation has greatly worsened in the last couple of years especially since 2012 when violent attacks against them perpetrated by the Myanmar army and Buddhist nationalists intensified following the report of the rape and murder of a Buddhist woman by Rohingya. The violent attacks against the Rohingya reached a new height last year after Rohingya militants attacked Myanmar security posts.

Presently the Rohingya are the most persecuted minorities in the world and their dreadful sufferings have been well documented by the UN and other human rights agencies. While a three-member UN Fact Finding Mission on Myanmar has reported mass killings, arson, rape, torture and worst kind of degrading treatment, the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights has described the situation in Myanmar as “a textbook example of ethnic cleansing”.

Fleeing persecution the Rohingya have taken refuge in places wherever they could go/reach easily and safely. While 700,000 of them have managed to reach Bangaldesh, an estimated 40,000 have taken shelter in various parts of India living in overcrowded, unhygienic and, diabolical conditions, in makeshift homes, with little access to potable water and proper food. In India around 15,000 of them are registered with the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) which is the principal UN agency dealing with the refugees but rest of them are without valid documents.

The principle of non-refoulement, embodied primarily in article 33 of the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, is the cornerstone of the international refugee protection. It seeks to prohibit a state from the return, expulsion or deportation of an alien, refugee or asylum seeker to territories whether his/her state of origin or another state where there is a risk that his or her life or freedom would be threatened on account of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group, or political opinion.

The principle non-refoulement also appears in varying forms and degree in a number of other instruments adopted later. Like Article 3 of the Convention Against Torture, 1984 prohibits a State to return a person to another State where there are substantial grounds for believing that he would be in danger of being subjected to torture.

Though the 1966 International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights does not directly and explicitly mention non-refoulement obligation of states but Article 7 provides that ‘[n]o one shall be subjected to torture or to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment’ and this provision has been interpreted by the Human Rights Committee in its General Comment No. 20 (1992), to include a non-refoulement component. It reiterates that States parties must not expose individuals to the danger of torture or cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment upon return to another country by way of their extradition, expulsion or refoulement.

It is true a non-signatory state like India is not per se bound by the principle of non-refoulement as articulated in article 33 of the Refugee Convention. But it can’t abdicate its responsibility under customary international law. Since the principle of non-refoulement has attained the status of a norm of customary international law all states are bound by it whether or not they are party to the Refugee Convention. Not only that the principle of non-refoulement is also ripe for recognition as a norm of jus cogens, from which no derogation is permitted under international law.

The second paragraph of Article 33 of the Refugee Convention, however, allows a state to derogate from the principle where there are reasonable grounds to believe that the refugee in question may be regarded as a danger to the security of the host country. Notwithstanding the security exception to non-refoulement it is subject to due process of law and can’t be invoked arbitrarily. It should also be underlined that the ideas of ‘security of a state’ and ‘refugee protection’ are not mutually exclusive; rather, they are complementary and mutually reinforcing.

India while defending its decision to deport Rohingya has put forward three pronged arguments. Firstly, it states that it is not bound by the non-refoulement obligation as it is not a signatory to the Refugee Convention and, though it has signed 1984 Torture Convention but has not yet ratified. Secondly, it has been argued that no-deportation of the Rohingyas would encourage influx of illegal migrants and thereby deprive Indian citizens of their fundamental and basic human rights. Thirdly, India has raised the issue of national security exception to non-refoulement.

All the three arguments put forward by the government is very weak, contradictory and suffer from legal infirmities. It is true that India is not party to Refugee Convention but that doesn’t completely absolve India from its non-refoulement obligation. India is a signatory to many human rights conventions containing the non-refoulement obligation albeit impliedly. For instance the General Comment 31 of the International Convention on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) the Human Rights Committee has stated that the obligation to respect and ensure the ICCPR rights “entails an obligation not to extradite, deport, expel or otherwise remove a person from their territory, where there are substantial grounds for believing that there is a real risk of irreparable harm.”

Similar observations have been made by the Committee on the Rights of the Child in its General Comment 6 to the Convention on the Rights of the Child. It states that “States shall not return a child to a country where there are substantial grounds for believing that there is a real risk of irreparable harm to the child.”

Besides these conventional obligations India is also bound by customary international law not to forcibly return any refugee to a place where they face a serious risk of persecution or threats to their life or freedom. Our courts have also interpreted the principle of non-refoulement as inhering in Article 21 of the Constitution of India and the state is bound to protect the life and liberty of every human being, citizen or otherwise. The judiciary on many occasions in the past has ruled against the forced expulsion especially when they feared persecution on their return.

Undoubtedly security is a legitimate interest of every State and is free to take any measure which it deems fit to protect itself and its population. But it would be unfair to deport all 40,000 Rohingya in India on a mere suspicion that some of them might get radicalised and hence may pose a threat to security. Our security agencies have so far not arrested even a single Rohingya on the charge of their connection with terror groups in Pakistan and elsewhere as often claimed by these them.

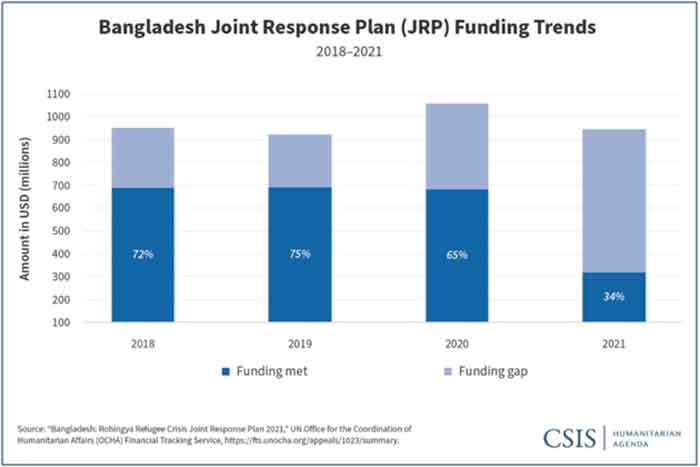

The economic and resource constraints are also often used against the continuance of Rohingya in India. It is stated that we are already hard pressed and hence can’t handle the large influx of illegal immigrants. The pumping in more resources to cater to the need of Rohingya would deprive our own citizens their genuine needs and would cause social tensions in the country. Indian fear in this regard is unfounded. If our poor neighbour Bangladesh can host more than 700,000 lakhs of the Rohingya, India can’t manage 40,000 of them? There are numerous instances when poorer countries have often shared even a much larger burden.

It should be also noted that the Rohingya in India are not being provided any assistance from the government agencies and are excluded from public relief programmes like food, healthcare etc. Some international agencies such as UNHCR are trying to help them out but they suffer from resource crunch and their presence is also limited. Rohingya live in squalid conditions and are engaged in menial jobs to eke out a living. It is intriguing that we are already hosting 3 lakh refugees from 28 countries and we further propose to welcome all Hindu, Jain, Sikh, Parsi, Buddhist and Christian refugees from neighbouring Muslim countries but we want the Rohingya deported. Why?

We should realise that the Rohingya are the victim of persecution and genocide and treating them as a cause of insecurity would be great injustice to them. We must hence strike a balance between our legitimate security concerns and our international human rights obligations. We should rise above the political considerations and in line with our long and rich traditions must extend benefit of non-refoulement obligation to the Rohingya.

The writer is a Professor of Political Science at Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh (INDIA).