The 2019 was the world’s second-hottest year on record. The World Meteorological Organization (WMO), U.S. space administration NASA and the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) announced the finding Wednesday. The Geneva-based WMO combined several datasets, including two from the NASA and the UK Met Office.

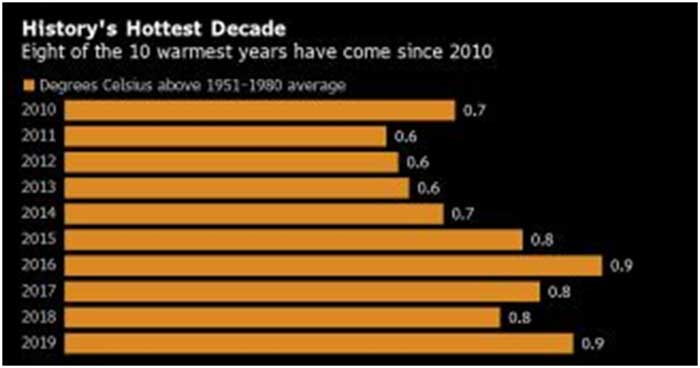

The decade beginning in 2010 was the hottest ever, and it’s the fourth in a row to set a new high. The five warmest years occurred since 2015. This year, 2020, is expected to be similar to 2019.

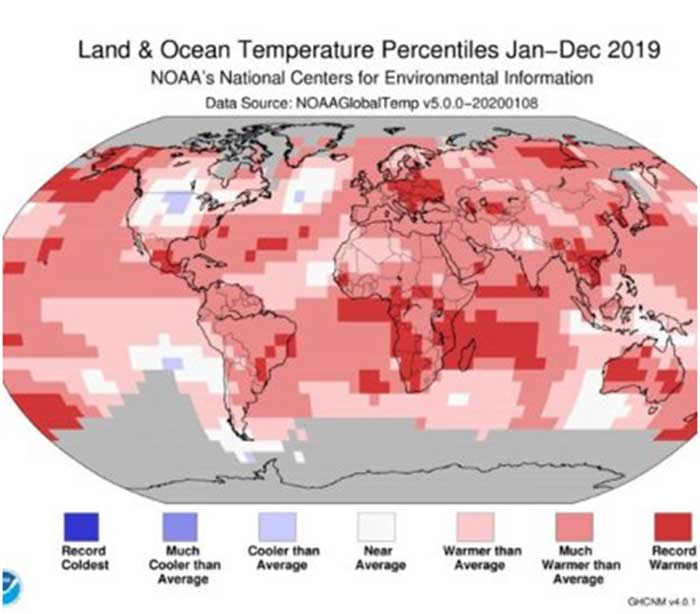

Under normal conditions, without warming, scientists would expect that 2.5% of the Earth would experience “very high” temperatures in a given year. In 2019, 52% of the Earth did. Almost 10% of the planet set local heat records for average annual temperature; no place broke a cold record, according to Berkeley Earth.

Other findings include:

- The U.S. saw 14 “billion-dollar disasters” last year, causing a total of $45 billion in direct losses. Most of that damage came from heavy rainfall tied to warming.

- Alaska saw its hottest year on record, with extreme drought and fires raging across the Arctic.

- Australia had its hottest, driest year ever, a precursor to the bushfires.

These showed that the average global temperature in 2019 was 1.1 degree Celsius above pre-industrial levels, creeping towards a globally agreed limit after which major changes to life on Earth are expected.

“Unfortunately, we expect to see much extreme weather throughout 2020 and the coming decades, fuelled by record levels of heat-trapping greenhouse gases in the atmosphere,” said WMO Secretary-General Petteri Taalas.

Scientists say climate change is likely to have contributed to severe weather in 2019 such as a heatwave in Europe and the hurricane that killed at least 50 people when it barreled through the Bahamas in September.

Governments agreed at the 2015 Paris Accord to cap fossil fuel emissions enough to limit global warming to 1.5 Celsius above pre-industrial levels, after which global warming is expected to be so severe that it will all but wipe out the world’s coral reefs and most Arctic sea ice.

However, the WMO has previously said that much greater temperature rises – of 3-5 Celsius – can be expected if nothing is done to stop the rise in harmful emissions, which hit a new record in 2018.

The U.S., the world’s top historic greenhouse gas (GHG) emitter and leading oil and gas producer, began the process of withdrawing from the Paris Agreement last year. U.S. President Donald Trump has cast doubt on mainstream climate science.

On a conference call with reporters on Wednesday, however, U.S. scientists said it was clear from the data that GHG emissions were warming the planet.

“We end up with an attribution of these trends to human activity pretty much at the 100 percent level … All of the trends are effectively anthropogenic (man-made) at this point,” said Gavin Schmidt, director of NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies.

The hottest year on record was 2016, when a recurring weather pattern called El Nino pushed the average surface temperature to 1.2 Celsius above pre-industrial levels, the WMO said.

“In the future we easily can expect warmer El Ninos than the previous ones,” said WMO scientist Omar Baddour. “We can raise a red flag now.”

Wildfires will be more common

Extreme events such as the wildfires in Australia are likely to become much more common as the warming trend continues, the WMO said.

Higher temperatures have been blamed for the severity of the wildfire season in Australia, which has killed 28 people and burned more than 15 million acres across the country.

Oceans: Hottest

It comes after scientists earlier this week said the world’s oceans were also the hottest on record last year, and had absorbed the equivalent to 3.6 billion Hiroshima atom bomb explosions over the past 25 years.

The team of climatologists reported on January 13 that the oceans were their warmest ever last year.

More than 90 per cent of excess heat is stored in the oceans, making them a key measure of warming.

Last year was only cooler than 2016, which was affected by the warming impact of a particularly strong El Nino climate cycle.

It also showed that average global temperatures during the past five years were also the highest ever recorded.

The world is currently on track for a warming of at least 3 degrees Celsius, despite climate change dominating the global political agenda.

For the first time, business leaders heading to the World Economic Forum in Davos next week identified climate-change related threats as the biggest global risks, a survey showed on January 15, 2020.

U.S. saw 14 billion-dollar -disasters in 2019

Major natural disasters, many related to rising global temperatures, cost $45 billion in direct losses in the U.S. alone.

The cause is well established: Fossil fuels contain high concentrations of carbon, so when we burn them for energy, they release carbon dioxide gas (CO2) into the atmosphere. That gas traps the sun’s heat, raising average temperatures across the globe.

“It doesn’t really matter which way you cut it,” Schmidt said in a press conference. “The fact is that the planet is warming.”

The NOAA tracks weather and climate events that result in over $1 billion in losses. The agency calls these “billion-dollar disasters.”

In 2019, the U.S. saw 14 of these events, at a total cost of $45 billion.

Floods were the most expensive, accounting for $20 billion of that total. The damage primarily came from three flooding events along the basins of the Missouri River, Mississippi River, and Arkansas River.

All three of those billion-dollar floods were triggered by heavy rainfall.

U.S. saw the second-wettest year

Across the U.S., 2019 was the second-wettest year on record.

“A warmer atmosphere is a thirstier atmosphere,” Deke Arndt, NOAA’s chief of global monitoring, said in the press conference.

That’s because warmer air can carry more moisture. In dry areas, that means warmer air sucks more moisture out of the soil, drying out vegetation and raising the risk of wildfires. In wetter areas like New England, it means that warm weather systems hold — and dump — more rain.

“We are definitely seeing trends in the instances of big rain,” Arndt said. “We’re seeing the largest events getting larger. We’re also seeing the larger events more responsible for a larger portion of the annual rainfall budget.”

Other billion-dollar disasters last year included Tropical Storm Imelda, Hurricane Dorian, and wildfires across California and Alaska.

Wildfires raged across Alaska in the state’s warmest year ever

The high US temperatures were most pronounced in Alaska, which saw its hottest year ever.

Amid the hot, dry conditions, unprecedented wildfires spread across the Arctic Circle in 2019. Alaska’s Department of Natural Resources had to extend the state’s fire season by a month as hundreds of blazes continued raging past the normal expiration date.

Some blazes even broke out within the Anchorage city limits. The city declared an “extreme drought” in August 2019 for the first time in the two-decade history of the US Drought Monitor.

In June alone, Arctic wildfires released 50 megatons of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere — the equivalent of Sweden’s total annual emissions. That’s more carbon than Arctic fires released during every June from 2010 to 2018 combined, according to the Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service (CAMS). The July wildfires released another 79 megatons of CO2.

The group said these were the longest-lived Arctic wildfires ever recorded.

Fires in Alaska and Siberia also deposited soot on the Greenland ice sheet, which darkened the surface and caused it to absorb more heat, contributing to its record melting over the summer.

The 2020s will probably be even warmer

NASA and NOAA scientists sometimes model what the climate would look like without human activity, using computer simulations to remove the effects of fossil fuels, agriculture, and forest clear-cutting.

“When we do that and we estimate what temperature patterns would be just because of those [natural forces], we end up with a massive discrepancy,” Schmidt said. “That tells us that the natural forcings are not capable of explaining the trends that we’ve seen since the 19th century.”

In the next decade, these climate trends are expected to get worse.

Even if all countries stick to the voluntary goals set in the 2015 Paris climate agreement, the world would still emit the equivalent of 52 to 58 gigatons of carbon dioxide per year by 2030. (This is measured as an “equivalent” in order to factor in other GHGes, like methane, which is 84 times more effective at trapping heat than carbon dioxide.)

So far, most countries are not on track anyway.

The data will feed the debate about how the world should respond to a shift in the climate. The $7 trillion investment house BlackRock Inc. this week vowed to sell its coal holdings. It’s becoming clear that there may be “this movement of global capital to actually do something on climate,” said Peter de Menocal, director of the Center for Climate and Life at Columbia University. “We may be turning that corner, and that is the real lever of change.”

SIGN UP FOR COUNTERCURRENTS DAILY NEWS LETTER