Trade Unions in Kenya and globally in the 2020s are very different from those in the 1950s. First, the global situation has changed a lot in the last 50 years or so. Prashad (2023) highlights factors that have impacted on the reality for trade unions:

Much has changed since the 1960s and 1970s, largely due to the new technological developments – such as satellites, on-line databases, container shipping – global commodity chains supplanted the old Fordist forms of factory production, weakening both trade union movements and the necessary strategy of nationalisation.

These changes enabled capitalism to reduce the power of working class by shifting production from countries with high wages to countries with low wages. Thus the key weapon of workers — strikes — was rendered less powerful than it was when capitalism could not easily shift production to other countries. Capitalism used its control over states to introduce ever restrictive laws for trade unions. In addition, technological changes meant that many jobs done by workers were either eliminated or became less important. Developments in artificial intelligence (AI) are likely to have similar impact on workers in the future.

Such changes took place in Kenya too and unions also saw a reduction of their power. In addition, trade unionism in Kenya suffered from other factors that further reduced their power from the early days. Before independence, the colonialists saw the danger to themselves of the power of unions when strikes affected key industries and energised the national struggle for independence. They thus brought in laws to reduce power of workers and their unions. The main impact was the separation of workers’ action on the political arena which they used to support their economic demands. Such laws have been retained and strengthened by the comprador ruling class today.

Yet, capitalism has not managed to suppress trade unions or working class militancy. That cannot happen while capitalist exploitation of workers continues. All the suppression of trade unions and worker rights cannot resolve the basic class contractions created by capitalism itself. The super-exploitation under capitalism results in worker militancy which, for example explains the militancy of workers in several European countries today.

So where do we go from here?

We need to learn from the history of Kenya and from other countries such as India and Latin America.

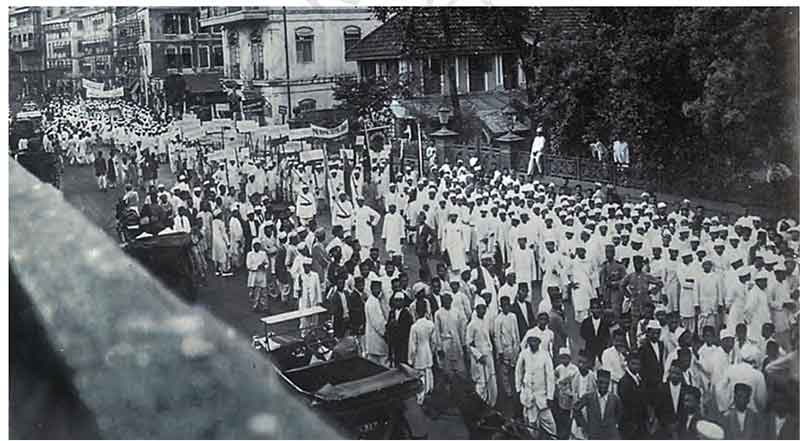

First, learning from the history of Kenya. Makhan Singh and EATUC linked their trade union work with politics as the only way to achieve their goals:

An important contribution that Makhan Singh made to the struggle for liberation in Kenya was to link the two aspects of a liberation struggle that imperialism sought to keep separate. These were economic and political aspects. Makhan Singh believed that in order to meet the economic demands of working people, it was essential to win political power first. It was only thus that foundations for an entirely different society could be laid.

That link between politics and trade union movement has been broken by capitalism and needs to be restored.

Makhan Singh highlighted another area for trade union work. Makhan Singh realised that for both the struggles — economic and political –- it was essential that people are politicised to understand the context of capitalism and imperialist rule which the country was under. Liberation could not come if only a few people in trade unions and politics were aware of the social and political contradictions in the society.

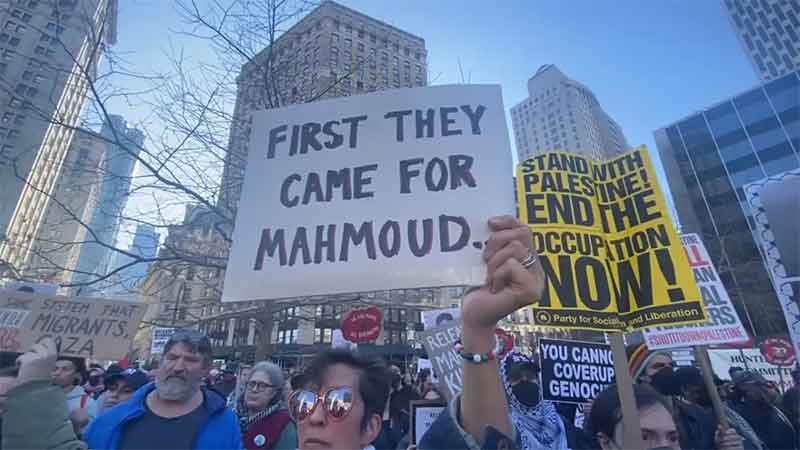

The emphasis for trade unions should be to go into working class communities and be part of worker’s live, not only in work places but in their homes too. International solidarity is also an important aspect for trade unionists. As capitalism spreads its influence globally, workers also need to support each other in different countries.

The lessons for trade unionists in UK are similar to the experience in Kenya. Doug Nicholls, the retiring general Secretary of the general Federation of Trade Unions GFTU) said:

The weakness in the movement has been that some think that our role is to manage capitalism a bit better than capitalists can.

Similarly, Gawain Little, the incoming general secretary of GFTU shows the context of trade union work:

We have to understand the economic system we are working within, the impact this has on workers’ daily lives and how it creates phenomena like the cost-of-living crisis. We have to understand the relationship between the industrial struggles we are engaged in and the political system within which those struggles are played out. Economics and politics are not two separate closed systems, they are integrally linked and we must be able to operate in both spheres at once, linking industrial campaigns to political power, exercised from the grassroots upwards.

However, the situation in Kenya is such that there is no viable national trade union movement that can take up workers’ and community struggles. At the same time, there is no political organisation that can take up the political and economic struggles of working class. A different strategy is needed to meet these conditions.

But a word of caution. Imperialism has twisted the meaning and content of the term ‘trade unions’ as a working class organisation. Thus the trade unions established by Tom Mboya and COTU are trade unions by name, but they do not represent the interest of working class. We need to be clear that trade unions are real weapons of the working class, not a window-dressing by imperialism. The very use of language has been distorted by capitalism, giving bourgeoise content to a weapon of class struggle.

Similarly, politics does not mean bourgeoise parliamentary politics. For workers and trade unions, politics is the ground on which the working class struggles for political and economic power.

Creating class consciousness among workers, finding ways for them to be active in the struggle through trade unions and its linked political movement in order to achieve socialism — such is the way forward for trade unions.

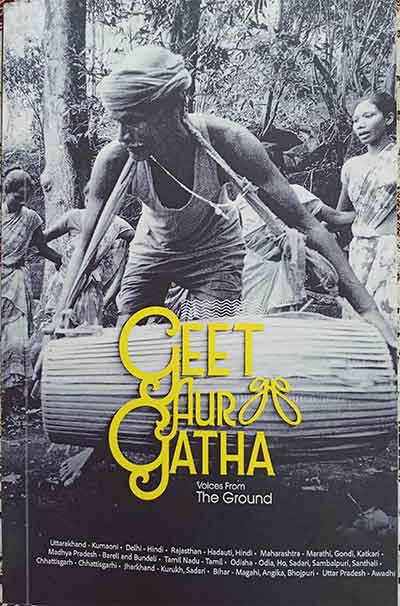

Shiraz Durrani is a Kenyan political exile living in London. He has worked at the University of Nairobi as well as various public libraries in Britain where he also lectured at the London Metropolitan University. Shiraz has written many articles and addressed conferences on aspects of Kenyan history and on politics of information in the context of colonialism and imperialism. His books include Kenya’s War of Independence: Mau Mau and its Legacy of Resistance to Colonialism and Imperialism, 1948-1990 (2018, Vita Books). He has also edited Makhan Singh – A Revolutionary Kenyan Trade Unionist (2017, Vita Books) and Pio Gama Pinto: Kenya’s Unsung Martyr,1927 – 1965 (2018, Vita Books). He is a co-editor of The Kenya Socialist. and edited Essays on Pan-Africanism (2022, Vita Books, Nairobi). His latest book (2023) is Two Paths Ahead: The Ideological Struggle between Capitalism and Socialism in Kenya, 1960-1990. Some of his articles are available at https://durranishiraz.academia.edu/research and books at: https://www.africanbookscollective.com/search-results?form.keywords=Shiraz+Durrani