Alpa Shah. 2024. The Incarcerations: Bhima Koregaon and the Search for Democracy in India. Gurugram, HarperCollins Publishers, India, pp. 561, Rs. 699.

When I picked the volume from a bookshop in Bangalore International Airport on my return from Hampi, a UNESCO-cited World Heritage site at the beginning of summer vacation, the general election campaigning was at its peak all over India. As the largest democracy in the world in terms of the election rituals conducted every five years, the protagonists of post-democracy in India exhibit a picture of the nation abroad- the ‘mother of democracy’. This image was further strengthened with the story of Narendra Modi- the rise of a man from the son of a tea vendor to the Chief Minister of Gujarat twice and the Prime Minister of India since 2014. The book under review questioned the tall claims about democracy and development in the context of the incarcerations of sixteen well-known social activists who stood for the rights of Adivasis, Dalits and Muslims. The biographies of the BK-16, the civil society activists who were put behind bars in the name of their alleged connections with the Bhima Koregaon incidents, showed the movements for democracy from below pulverized by the right-wing fascist regime.

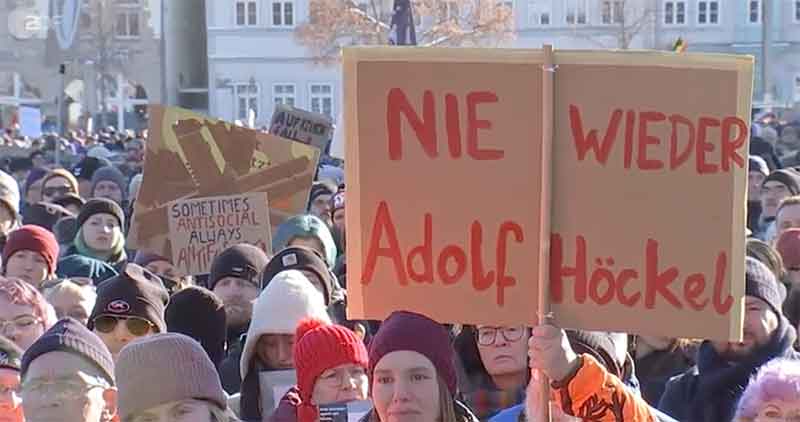

Neoliberalism, the ‘movement from above’ (Cox & Nielson 2014), denounced the institutions of democracy, and called for a militaristic state apparatus to repress the resistance ‘movements from below’. The quest for decentralization is a risky business though the people like indigenous forest dwellers struggle hard to safeguard their natural environment from the profit-thirsty multinational mining corporations. The daily battles of Dalits against caste oppressions, their struggles for land, and the Muslim resistance against the forceful exclusions of Hindutva majoritarianism intensified conflict between the state and the poor people in India. Their voices were democratically been amplified by the activists in the civil society though the ruling class perceived the movements as ‘anti-national’ and new connotations ‘Urban-Naxal’ and ‘Urban-Maoist’ de-spatialised the targets- therefore anyone who dared to speak against the regime would be dealt with the draconian law UAPA.

The book was set in the background of Bhima Koregaon incident that happened on the first of January 2018 and the subsequent arrest of sixteen human rights activists from different parts of India. The Dalits regarded the Victory Pillar in Bhima Koregaon as the symbol of their resurrection against the caste-ridden Peshwai Empire- where the Dalits experienced the worst form of caste oppression. The Hindu-Right forces were campaigning against Dalit commemoration as ‘anti-national’. The question- of why Dalits supported the British against their rulers has not been addressed. Since 1927, Dalits have been celebrating every first of January as Victory Day. In the first meeting, B.R. Ambedkar addressed the Mahar gathering and supported the idea of an annual commemoration to revive the valor of their forefathers. This has given new strength to Dalits in their contemporary fight against continued caste oppression in India. In the 2018 commemoration, the Hindutva supported people unleashed brutal violence against Dalits who gathered in Bhima Koregaon. In response to widespread protest from Dalit organizations, a ten-member citizens committee was formed to enquire into the issue. The deputy mayor of Pune was also a part of the committee. They have submitted a report to the police with more than two hundred photos and videos which substantiated the argument that the violence against Dalits was orchestrated and implemented by people and organizations with a Hindutva agenda. When the issue was pointed to two prominent figures who have close connections with the Sangh, everything took a U-turn.

The Author argues the arrest of BK-16 was the outcome of a conspiracy, a naked exertion to save the perpetrators at the expense of the people who stood for the rights of the destitute. The book begins with a prologue and a detailed introduction- dealing with the link between Corporates and the Hindutva movement, the rise of authoritarianism and social movements for democracy in India. The book is further divided into Nine Parts, narrating the stories of BK-16, begins with Sudha Bharadwaj who devoted her life to the rights of the Adivasis of Chhattisgarh state-‘a rich land of poor people’. By ‘de-classing’ herself to go much deeper into the life world of the indigenous people, Sudha was able to address the multi-faceted issues faced by the Adivasis in the region. From labour rights to a much wider fight for land, forest and environmental rights of indigenous people, Sudha unveiled the unholy nexus between the state and the Corporates and exposed some of the most horrific human rights abuses in the world. Also, Sudha supported the local activists to establish the ‘Save Chhattisgarh Movement’ an initiative to unite various people’s resistance movements, to learn from each other, and to support each other against displacement. It also allied with the anti-displacement movements of Odisha and Jharkhand, where Stan Swamy had formed a similar initiative called ‘People’s Movement against Displacement’. Moreover, Sudha Bharadwaj showed through various examples that a serious leftist movement could not be separated from grassroots movements of the deprived sections. Also, the movements could not be detached from the necessary legal battles-‘paper fight and the street fight’- using the Indian Constitution itself to safeguard the democratic rights of the poor people.

The second part of the book tells the story of Stan Swamy, a Jesuit Priest who dedicated his life to the poor of the poorest people in the state of Jharkhand. Stan addressed the issues of displacement, various laws about the protection of Adivasis land and forests, the impact of the Forest Rights Act, the use of Adivasis in counter-insurgency to kill other Adivasis, the ‘Hindutvasation’ of Adivasis space, and most importantly he worked hard to raise the issue of the under-trialed in various jails in the state. The majority of the under-trialed are Dalits and Adivasis, who could not afford even the trip from their villages to the jails in the town. Many of them did not know the specific charges framed against them and did not understand the language of the courts. To them, the state seems to be an alien institution joining with the rich to devastate their life. Stan observed that the majority of the incarcerated were the victims of ‘development-induced displacement’. Stan and his team prepared a detailed report on the under-trialed and published. Therefore Stan became ‘a thorn in the flesh of the state’. Bhima Koregaon case was used to ‘silence’ him!

Prof. Anand Teltumbde, a renowned public intellectual having a different approach to social movements, particularly regarding the right assertions of Dalits in India, was also a target of far-right forces in India. Through various works such as the ‘Republic of Caste’, he emphasized the importance of linking the issue of ‘caste’ and ‘class’ in the fight against neocolonial exploitation. As a critique of caste-based reservations, Teltumbde observed the reservations had created an elite class within the Dalits and fundamentally it was not beneficial to a vast majority of Dalits. Therefore raising Dalit consciousness beyond the pre-set reservation boundaries of the state is the need of the hour. His outlook on social movements was rooted in Ambedkar’s idea of the ‘annihilation of caste’. The third part of the book concludes with the observation that ‘Anand Teltumbde’s ideas represent a significant alternative and challenge to the right-wing appropriation of Ambedkar and thereby Dalits.’

Part four of the book begins with the historical importance of Bhima Koregaon in the context of the ongoing Dalit resistance against the Brahminical impositions. Subsequently get into the narration of Anita Sawale, a thirty-nine-year-old anti-caste activist, who was an eyewitness of the whole incident that happened in Bhima Koregaon on the first of January 2018. The chapter unraveled the politics of the perpetrators, the Sangh people, who had historically been disturbed by the victory of the Dalits over the Brahminical upper caste rule. The present Hindutva dispensation knows very much that such commemoration is indeed a vital threat to the political and cultural absorption of Dalits and Adivasis into the right-wing nationalist agenda; therefore Bhima Koregaon was a target of the Sangh. The fifth chapter examines the twist that happened in the whole narrative. When the reports on the 2018 riots turned against the people who were behind the curtain, an entirely new narrative was developed, with a new plot- ‘a chilling Maoist conspiracy to assassinate Prime Minister Modi’. This was pointing to the Elgar Parishad, a conclave of diverse Dalit groups, Muslim organisations, Adivasi groups and even some Maratha groups for spreading the message of fighting communal and neocolonial forces. Many of the group members participated in the Bhima Koregaon New Year’s Day celebrations of 2018, where the blue-flagged people were widely tortured by the right-wing supporters. Subsequently, the coordinated multi-city police raids and the arrest of sixteen civil society activists, particularly those who were opposing the right-wing political agenda, was also an attempt to raise the dust to escape from the Dalit atrocities committed by the Sangh supporters.

The book argues there was a conspiracy to trap the BK-16. The letter detected by the police from their computer systems was the ploy of a Trojan horse, a malware that can be used to plant files or edit texts from distant locations without knowing the user. When Stan Swamy, Sudha Bharadwaj, Anand Teltumbde and some other accused saw the alleged letters circulating in the media, they put out public objections on various forums; however, their protestations had no impact. The sixth chapter gives a detailed examination of the various aspects of the technical reports, and mismatches with the police version of evidence. Many news sites reported the critical role of Pegasus, a powerful spyware, made by the NSO Group, an Israeli cyber surveillance company. The close tie-up between the current ruling dispensation in India and Israel has also to be noted. Most commonly, the right-wing governments are too obsessed with national security- a safety mechanism for the unfettered capital accumulation under neoliberalism.

Part seven of the book was about Gautam Navlakha, a democratic rights activist and journalist who had been associated with EPW for more than three decades. He extensively worked on the issue of human rights violations in Kashmir. He was part of various fact-finding teams in the valley. The arrest of Gautam signaled a clear message to those who were advocating the rights of Muslims in India. The chapter further explains how the right-wing systematically de-grading the Muslims in India as second-class citizens, and asserted that the very process of ‘Self’ construction has been intensified under Modi Raj. The introduction of CAA, abrogation of Article 370, abolition of Article 35 (A) and the attempts to impose the Uniform Civil Code show the march of fascism, pulverizing the ethos of Indian democracy.

‘The process is the punishment’ is the title of part eight which talks about the draconian law UAPA. All the BK-16 were jailed under this law. The bracketing of the people as ‘Urban Naxals’ or ‘Urban Maoists’ is a new strategy so that the governments can easily quell the dissent voices. The prison experiences of Stan Swamy and Varavara Rao in the BK-16 case are a testimony to the inhuman nature of the UAPA law. The law was intended to fight against terrorism, however since Narendra Modi came into power in 2014, the law had been specifically used against the people who had persistently supported the movements from below against rising inequality, land grabbing, state atrocities, and protecting environmental, land and forest rights. The final part of the book ends with three simple sentences: ‘The seeds of democracy will be preserved within fascism. One day they will have the conditions to flourish. This is where the hope for our common future lies’ (P.498). Fascism is only a temporary political phenomenon. The ruling class embraces it as a safe framework for smoothening the process of capital accumulation. The life situation of the poor is getting worse day-by-day. The movements from below are expected to make qualitative changes in Indian democracy.

Reference

Cox, Laurence and Alf Gunvald Nilsen (2014): We Make our own History: Marxism and Social Movements in the Twilight of Neoliberalism, London: Pluto Press.

P.M. Joshy (Ph.D.) is an Assistant Professor in Political Science, Sree Narayana College Chempazhanthy, Affiliated to the University of Kerala, Thiruvananthapuram. He has authored a book with Prof. K.M. Seethi entitled State and Civil Society under Siege: Hindutva, Security and Militarism in India (Sage India, 2015).