Amid the twin issues of Caste Census and Sub-categorization of reservation of SCs/STs and ‘creamy layer’ among SCs, it must be remembered that caste issues have always been tweaked and twisted by politicians for their windfall gains to fortify their political positions in the name of social justice.

Sub-Categorization of Reservation

Why sub- categorization within SCs on the first place? Is there any difference in discrimination and violence that they face being Dalits between the dominant Dalits and the other sub-castes from the same community. They have always been treated alike. It is only a matter of creating skirmishes and apprehensions within the sub-SCs. Flaunting promises of social justice and reshaping reservation policy sounds fascinating but have hardly served any purpose in development and mainstreaming of Dalits. Speaking of sub-categorization of the SCs the upward mobility might be different for different sub castes among Dalits but the stigma attached with concept of untouchability in society is same for all Dalits. More so the Supreme Court came up with the verdict/ruling without any proper research and data in hand and without the definition of ‘creamy layer’, which make it completely unjustified. Sub-categorization of reservation can be justified only if it ensures uplift of least deprived Dalit not merely have purpose to attain political goals.

Caste Census

Caste census is important because without enumeration the problems and issues of the historically discriminated caste groups cannot be resolved. The resource distribution and policy formulations for such communities may not fit in properly. Therefore, administrative purposes also the caste census is a must. However, the present political scenario is conducive for the caste census as the incumbent government and opposition have agreed for the caste census but what is required, they shall come with the inclusion of caste census as a part of regular decadal census. Criticising the caste census, social scientists such as Marc Galanter have argued that the census recording of social precedence is a device of colonial domination, designed to undermine as well as to disprove Indian nationhood. They contend that even assuming that caste data are relevant, enumeration of the population on the basis of caste is bound to be vitiated by vote-bank and reservation politics, leading to the inflation of population figures and the suppression or distortion of vital information on employment, education and economic status, among other things. (Frontline, Sep.02 2000)

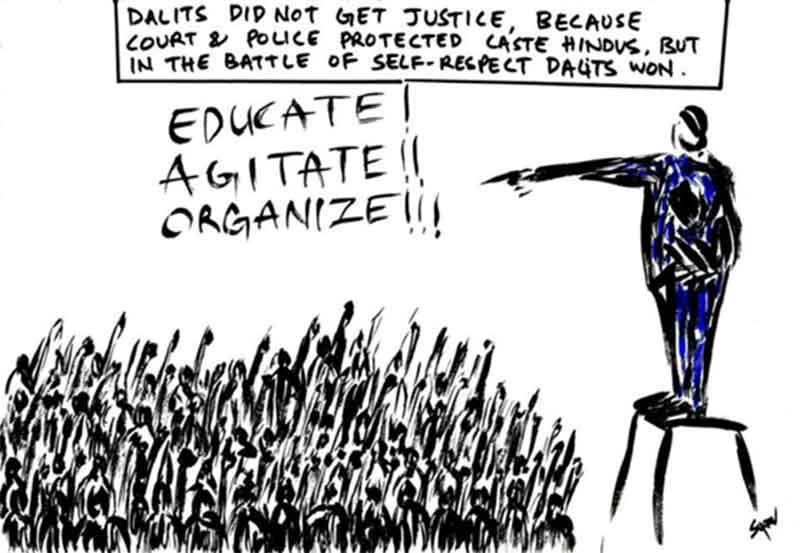

Violence against Dalits

Unlike trauma associated with holocausts and natural disasters the consistency of trauma associated with Dalits, have a much longer standing and have much comprehensive associations, complex heterogeneity. violence against Dalit is a fact, a reality ingrained in the very psyche of the people in India. In order to cure the prejudiced society from all-pervasive, diseased orientations and attitude, the state being the agent of social justice and custodian of fundamental rights has made efforts to uphold the ethos of constitution, ensuring liberty, equality and justice to Dalits incorporating the concepts like protective discrimination in certain spheres.

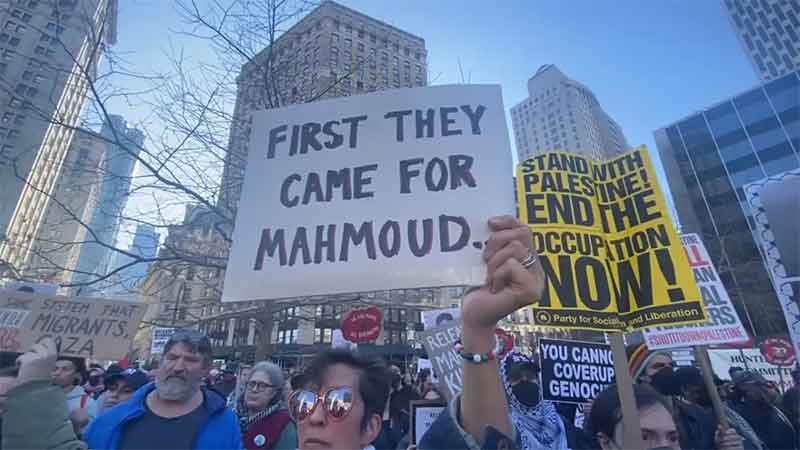

But the question remains, why even after nearly eight decades of independence we come across barbaric and lethal acts of violence by the dominant or the upper-castes as has been seen in the cases like Bathani Tola (1996), Laxmanpur Bathe (1997), Gohana (2005) Khairlanji (2006) and cases of special category like Jisha’s and Delta Meghwal’s rape and murder case, Saharanpur (May 2017) case of killing and arson, Hathras gang rape and murder case (2020),Lakhimpur Kheri (2021). Others everyday happenings are, Denial of Haircut in a barbershop; denial of entry in places of worship; killing Dalit boys for having love-affair with an upper-caste girl; forcing Dalit women to call herself a ‘witch’. Where, in most of the cases, the victims remain un-booked, roam acquitted and the hapless life of a helpless Dalit poor follows life threats throughout the remaining life. Sociological and political enquiries says that there are different kinds of discrimination and violence in rural and urban spaces.

Defaults in Rural Settings

Corruption is the process, of which exclusion is a significant result that can rattle an entire community and abstain them from raising their voices against injustice. Persistent exclusion helps to sustain existent social inequalities. Here it can be argued that corruption, exclusion and inequality are intricately related. Here I remember Craig Jeffrey (2001) who has convincingly justified that any such thing like ‘corruption and caste reproduction’ do exist in developing countries like India (a highly caste stratified society) and work is scarce on it. Through his anthropological study of caste, class and clientelism he has critically analyzed how corruption at grassroots that results in economic inequality helps in keeping the social inequality intact through three sorts of equations between the local state, local elite and the marginalized.

The state’s inaction has been seen as violence, in the form of death caused by poverty through hunger, malnutrition. Another fragile population is marginalized sections: Dalits, tribals, backward castes and women who often face violence and indignity in society and come across states inability to bring them justice. Such an attitude has been becoming more and more tolerant without asserting their demands. More so, this has been eroding legitimacy and enhancing trust-deficit among people towards governance.

The Invisible State Violence

Looking at the inaction of Indian state Akhil Gupta (2012) in his famous work,”Red Tape” has mentioned that, “What makes violence invisible? How does one describe violence in the absence of events like communal riots, or the displacement of people by dams and other spectacular development projects, or police or army brutality? What are the juridical and social conditions that make the violence like this taken off or granted in the routinized practices of state institutions such that it disappears from view and cannot be thematized as violence at all? I am concerned with what should be considered exceptional, a tragedy and a disgrace, the invisible forms of violence that results in the deaths of millions of the poor, especially women, girls, lower caste people, and indigenous people.” Such practices still existent in the countryside no matter how many welfare policies have been rolled out to benefit the poor. Who is the poor? The marginalized – Dalit, Adivasi, Women, Backward.

No Caste in Urbanized Space?

Savarnas says that “with urbanisation the caste discrimination has vanished. It has taken new adaptations and discrimination do exist in urban settings. Social Science Research has shown that there exist modern forms of discriminations in urban spaces. Ashwini Deshpande (2016), speaks about a neo-caste system that, “there is a wealth of evidence on the long-standing disparities in material outcomes by broad caste groups: education, occupation, consumption expenditure, wages, asset ownership etc. Many believe that these disparities are either largely rural or a hangover of discrimination in the past. Deshpande has further discussed that, “research has shown that employers, including MNCs, use the language of merit. However, managers are blind to the unequal playing field which produces “merit”. Their commitment to merit is voiced alongside convictions that merit is distributed by caste and region. This results in a process where qualities of individuals are replaced by stereotypes that at best, will make it harder for a highly qualified job applicant to gain recognition for his/her skills and accomplishments.

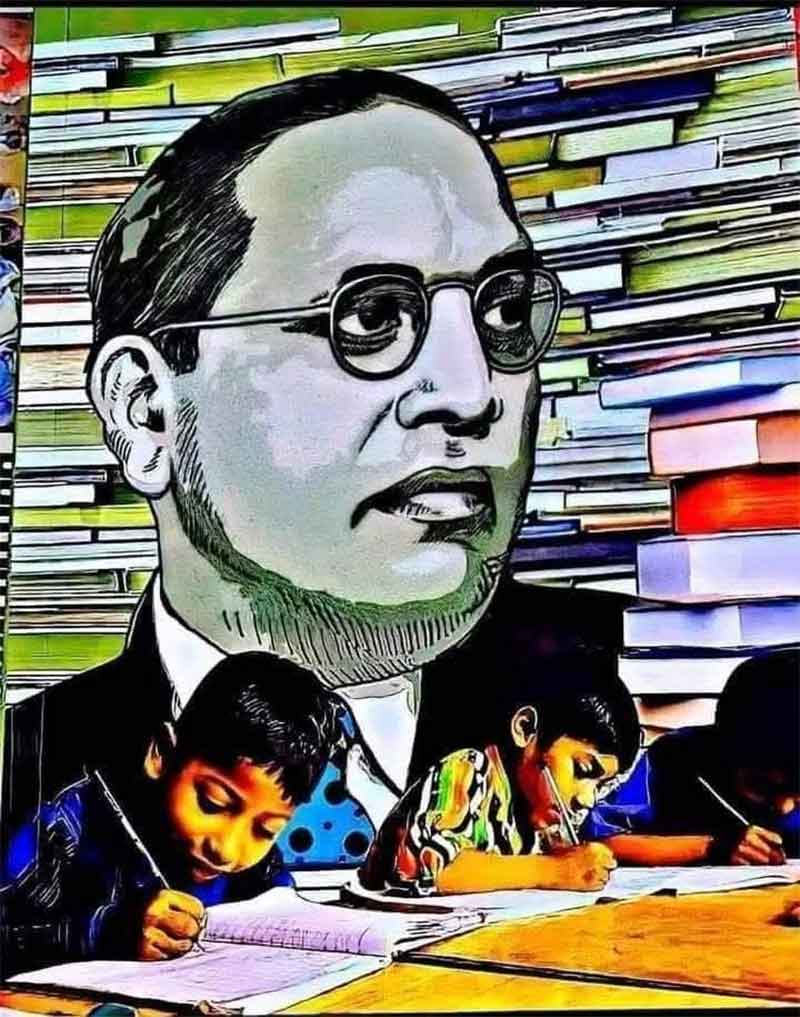

Whereas the government has always been busy in fulfilling their political motifs, what they propose every-time that gets glossed in public as social justice and welfarism, the ground reality is quite away from such trumpet and remain disadvantaged to the disadvantaged community. No matter what until the marginalised will realise the utility of the words of Manyawar Kanshi Ram, “Jiski jitni sankhya bhari, uski utni hissedari (The greater the number, the greater the share)”, to get into power, the situation will remain the same. As Dr BR Ambedkar said “Institutional change in India is not going to make any difference. The persons who are holding these institutions need to have attitudinal and behavioural changes in themselves”.

Dr. Renu Singh, Taught at Amity University, Lucknow, Ph.D in Political Science from Jamia Millia Islamia, New Delhi