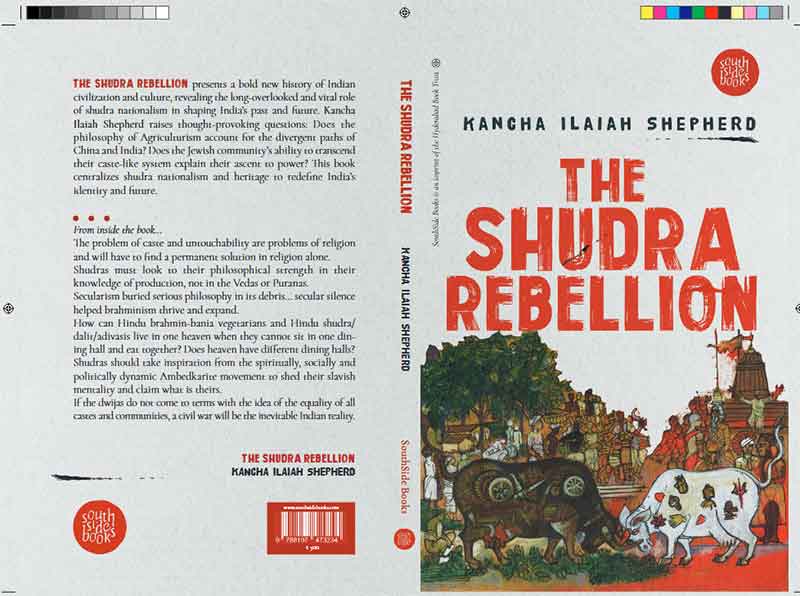

This is the final chapter of Kancha Ilaiah Shepherd’s, groundbreaking work ‘The Shudra Rebellion‘ that promises to reshape our understanding of Indian civilization and culture. In this compelling book, Ilaiah boldly unveils the often-overlooked role of shudra nationalism in both India’s past and its future. Ilaiah’s work pushes us to reexamine the very fabric of Indian identity through the lens of shudra heritage. This book is not just a historical account; it’s a call to awareness and action. Ilaiah’s insights resonate in today’s socio-political landscape, making it an essential read for anyone seeking to understand the complexities of caste, identity, and the future of India.

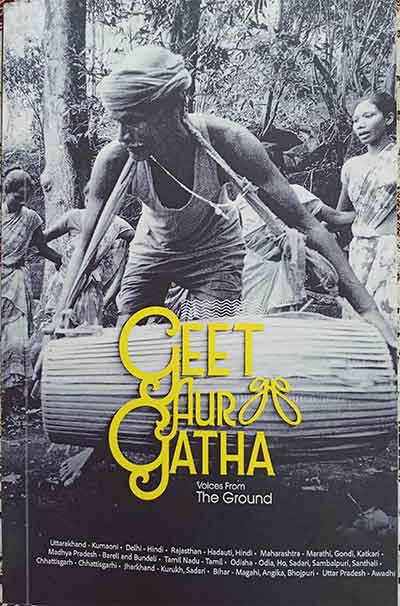

The history of the Shudras is far older and deeper than brahminic written history. It goes far beyond the Vedas, Ramayana, Mahabharata and Upanishads, and remains outside all these books, without getting mentioned in any significant way. However, shudra history survives and exists in the furrows of agrarian lands and in artisanal fossils and living tools. The living shudras are also a huge repository of their past and present history. India’s science exists in these unwritten furrows and in the deep wells of the wealth of labour. This nation’s future has to be built, taking lessons from these sources.

RECLAIMING SHUDRA IDENTITY WITH PRIDE

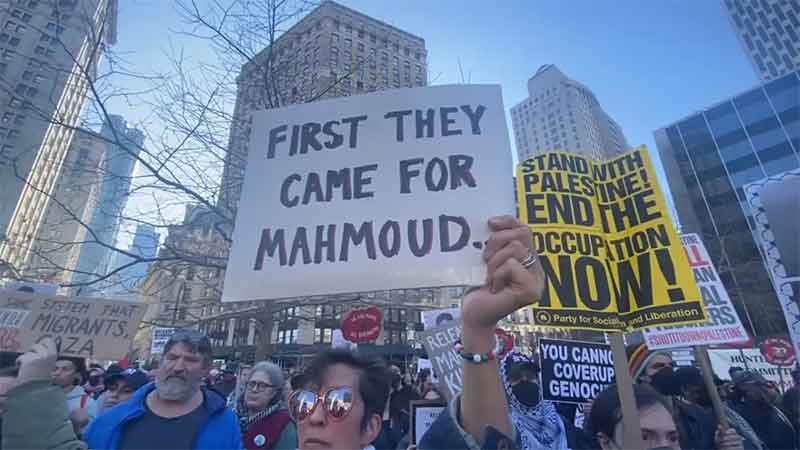

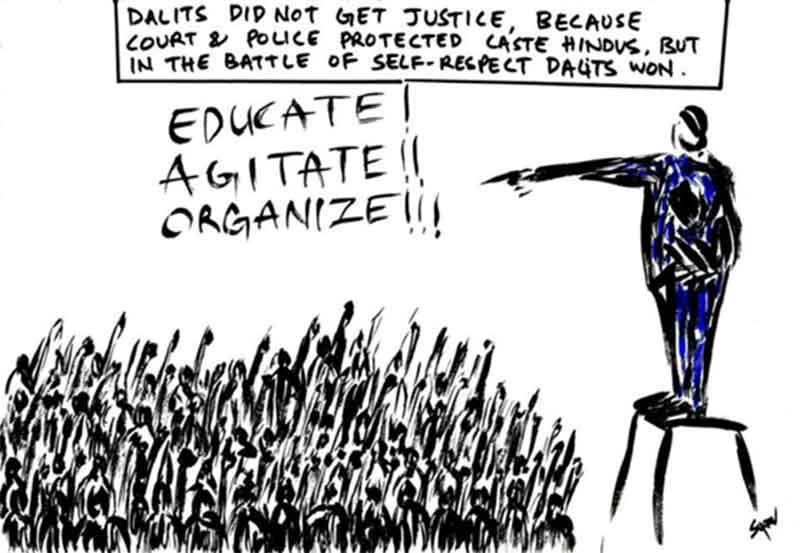

The shudras must deploy the identity ‘shudra’ as superior to the identity of the brahmin. Though shudra civil society is fragmented into myriad layers—each layer with its own name as caste or jati, their classical unified identity as shudra must become a political entity. Any identity acquires respectability only when its owners are proud of being identified with it. In modern times a woman is proud of being a woman, a dalit is proud of being a dalit. Similarly, a shudra has to be proud of being a shudra. This pride demoralizes the Other who earlier used that identity as undignified.

Secondly, the shudras must look to their philosophical strength in their knowledge of production, not in the Vedas or Puranas. They cannot look for their strength where it does not exist. They cannot look for their strength in the history of some shudra rulers. No shudra ruler in Indian history operated outside the framework of brahminism, particularly after Kautilya wrote his book Arthashastra and Manu wrote the Dharma Shastra. All shudra rulers were converted to kshatriya status and forced to obey the orders of Brahmin priests.

The day-to-day discourses of shudra food producers are replete with philosophical, economic and scientific thought. Unfortunately, this thought has not been recorded and textualized. Since most of their socio-economic and spiritual history is in the villages, young intellectuals of good calibre must engage in textualizing it.

Shudra civilization is spread out in many regions and states and is recorded in some regional languages and oral histories. Several scholars must undertake the painstaking work to study and write about shudra philosophy, science, and economics, in all regions and states mainly in English. Though it is not an easy task, given the denial of their history for millennia, it is possible to retrieve it.

UNEARTHING SHUDRA HISTORY THROUGH TOOLS OF PRODUCTION

There is a major task at hand for shudra voters, activists, leaders and rulers, whether at the state or central levels, to establish good museums of artefacts of production, social use, cultural use and architectural value that survived the historical neglect of the brahminic negative knowledge system. Indian agriculturist and artisanal forces constructed highly sophisticated tools like spades, buckets, pots, plough, ropes, construction materials like bricks, cots, hunting and fishing instruments as time, production, and survival demanded. By the time the shudras built the Harappan civilization, they constructed houses with burnt bricks and built their homes with crafted wood. At the time, the migrant Aryans had no knowledge of such civilizational technologies. Tools and technology development happened much before the Aryans arrived and constructed the ideology of brahminism. They did not help in the scientific process of life. The dwijas do not exist in these realms of knowledge even today. They consider that making technological instruments is an act of ritual pollution.

Millions of instruments went into oblivion without getting written about or their shapes and uses sketched. Pre-Independence times stored brahminic music or written material in museums, libraries and temples. Kings, whether shudra or dwija, gave importance only to divine idols and sculpture. Even the erotic life of brahminic society was preserved in the Khajuraho and Konark temples, but no king built an agrarian artisanal museum. No ruler had a contemporary sculpted plough placed in a temple. This only shows that agriculture, which is the mother of all cultures, had no value in any mode of civilizational history under pre-colonial, colonial or postcolonial rulers. So far, shudra rulers have not shown any concern for agrarian artefacts or understood the need to museumise them.

As a result, this ancient civilization did not preserve the fundamental source of its culture, science, technology and history. Anti-science brahminism made us slaves of the Euro-American knowledge systems. Hence India borrows science and social science knowledge from them even in post-colonial times.

The shudras must now strive to build many museums of agrarian and artisanal instruments, and write about their modes of use. For example, there is repeated mention of soma (in modern times, this drink is known as toddy, called kallu in Telugu) even in brahminic books like the Vedas. But nobody wrote about what kind of technology was used to tap the drink from trees. Toddy tappers use moku, mutthadu and guji to climb a tall toddy tree, even in modern times to harness the drink. In ancient times too, the tappers of soma must have used several instruments and techniques, but there is no record of these technological instruments.

A toddy (sura) tapper has to climb a tall tree that has no branches to tap the drink at the top and bring it down. Using these instruments and risking their lives, tappers do this hard labour with great scientific skill. Every day, the tapper climbs several trees and brings down the drink from the top of the trees. They use the moku to support their back, placing this around the tree stem, while their hands are pressed to the tree. The guji keeps the feet pressed to the tree. The mutthadu holds all kinds of sharp knives that are used to cut the trunk to get the drink from the tree.

Likewise, several shudra occupational groups use different technological instruments to perform their skilful tasks. Many such technologies are going out of existence and their history erased if they are not written about. Museums of such tools will be great historical resources of knowledge to remain for millennia.

THE DECLINE OF SHUDRA SCIENCE UNDER BRAHMINISM

Parasitism always sustains itself by constructing myth as philosophy. Whether they are philosophical ideas like Dwaita or Adwaita, Vaishnav or Shaiva, they operate outside the realm of production. They are different names for brahminism. Shudra thought has to operate outside this realm without fear or sentiment. Courage emerges out of conviction. Even in modern times, the shudras have not shown courage in the realm of constructing knowledge and ideas. Not that they do not have ideas, but the fear of the brahmin destroys that energy that could give a concrete written shape to their ideas. Not that they do not have spiritual ideas that sustain their socio-spiritual life in villages where brahmin mythical philosophy and recitation of mantras are not around them. The agrarian people survived for millennia without any connection with a brahmin. But brahminism spread to every nook and corner of village society and made the whole shudra population believers in mysticism. The injection of mythical philosophy now controls their consciousness.

Ever since their ancestors asked questions about agriculture like how a seed placed in the ground germinates and grows, how a bird flies while a man walks, where the wind that touches the human body or sweeps over their crops originates and where it ends, they discovered new things. Our shudra ancestors who were the initiators of seeding and growing crops from the earth and who interacted with birds and animals daily, must have concluded that an unknown power was operating behind all these movements of nature. This spiritual resolution was a higher philosophical one than the question that the brahminic dwaita or adwaita thinkers asked. When the answer was found, it made sense to them only concerning seed, plant and crop. The historical shudra spirituality was a mix of Science and God. Brahminism negated this scientific spirituality and advanced mythical spirituality killing the capacity to reason out the process of life. Once brahminism gripped shudraism, Indian agrarian and artisanal science began to stagnate.

DEVELOPING A SHUDRA INTELLECTUAL MOVEMENT

A well-trained intellectual force must emerge from among the shudras. Though compared to dalits, the shudras have more land and property, they have not yet produced an intellectual force that can focus on writing their history and philosophy. Since their wealth operates mostly around the agrarian economy, they still have the peasant understanding that reading and writing are not important.

Most agribusiness is in the hands of upper shudras. They have emerged as real estate financers around urban centres. They are also well-established in regional politics. The OBCs within shudra society have become conscious of the necessity of reservations and also education but they live only in non-philosophical realms. Low-end achievements in medical science and engineering are visible among them. But a broad historical and philosophical knowledge requires deeper involvement in philosophical, sociological, and spiritual discourses with the ability to read and write methodically in these schools of thought. Even rich shudras have no conscious intellectual force trained in Indian or foreign universities to handle these philosophical and social science issues. They have to get out of the grip of brahmins and their superstitions. Mere literacy and technical education do not reframe their mental abilities.

A strong will to have an identity for themselves, outside the boundaries of brahminism is a prerequisite. Brahminism now operates in the new construct, ‘We are all Hindus’. The shudras have no equal space in this Hinduism. Shudra thinkers and writers should operate in their production-centred philosophy and sociology as hegemonic, even in the domain called Hindu.

The ideas of hegemony are constructed consciously by thinkers to control the Other. Shudras were and are the historical Other for dwijas, though they do not realize this. Normally, the construction of philosophical knowledge not only comes from deeper study of the society that one lives in, but also comes from constant engagement with ideas. This requires leisure and resources. It is the rich shudras who need to spend part of their wealth in the philosophical sphere. Among the shudras, the marathas (Maharashtra), reddys and kammas of the Telugu states, patels (Gujarat), jats (Uttar Pradesh and Punjab) and others have to get into this identity discourse and invest their resources in training their youth in India and abroad.

Though the nairs of Kerala are shudras they want to be in the fold of the dwijas; they want to be called savarna and are not willing to oppose brahminism. They also work as anti-reservationists, just as the dwijas do. One of the strong historical reasons for this is that nairs had a deep blood relationship through the system of sambandam with the brahmins of Kerala. However, their agrarian and artisanal roots are still strong. In the 21st century when the RSS/BJP rule with the idea of turning India into a classical varna dharmic state called the Hindu Rashtra, it is for them to take a call towards serious study of their millennial roots and history as shudra agrarian people.

Shudra intellectuals must acquire sophisticated skills to build a written knowledge resource of the history of production. Global knowledge to create modern literary texts is equally important along with reading what is available in India.

SCRIPTING A LANGUAGE OF EQUALITY AND DIGNITY IN REWRITING SHUDRA HISTORY

Shudras must realize that they must fight for English medium education in government schools. Only when a large number of children who are still engaged with the agrarian environment, labour and nature are in school, is it possible for them to emerge as world-class intellectuals over some time. But all of them must get English medium school education in their village environment. The theory that English is a foreign language and very difficult to learn in Indian village schools is a lie. All children, irrespective of their caste, and class can learn English if a conducive school environment is provided to them anywhere. The village environment, which is surrounded by agrarian production, is better suited for dignity of labour centered English medium school education. Reading, writing, and formulating intellectual energy should begin at the school level. Shudra children were denied this learning for millennia. They must get it at least now.

The history of the shudras was ignored in writings in Sanskrit, Persian, and other national languages all these years. Now this history must be written in English to receive universal recognition and use value for global scholars. A history written in a rich global language will get global attention and the use of that knowledge will help the world, not just India. Shudra history, unlike brahminic history, has many global commonalities. Added to this, a new philosophy, if written in a rich language like English, displays depth and force. Shudra youth do not have to spend their energy to study Sanskrit, when dwijas themselves have shifted to English; they should not waste their time and energy to retrieve a dead language.

This history must be written in the collective combination of shudra/ dalit/adivasi intellectuals so that it unravels all forms of exploitation and oppression by dwijas who injected human untouchability among the dalits and kept adivasis outside modern civil society. Intra-productive community problems should be resolved outside the caste cultural framework. Man-woman equality in all communities should be a common concern. There is great need for dwija women to engage with this knowledge construction because this history has the potential to weaken patriarchal control over Indian society and the state.

A NEW FRAMEWORK FOR SHUDRA HISTORIOGRAPHY

Shudra history, if properly written by applying the Marxist method, could have given Indian Marxists a better direction to change this nation in a meaningful way. A creative Indian communist ideology rooted in the nation’s production relations could have prevented the growth of Hindutva nationalism. Shudra nationalism and brahmin nationalism are antagonistic in day-to-day operations. In a situation of all-round failure to write and preserve production knowledge in this country possessing the oldest civilization in the world, shudra thinkers must write this unwritten history in a new creative way.

My attempt to study Indian history through the shudra experience, starting with Why I am Not a Hindu (1996) and finally writing this book on shudra history tracing back to the Harappan civilization is a step forward. It is meant to help future historians, sociologists, and philosophers to do more concrete work on shudra civilization, culture and philosophy. The slogan `garv se kaho hum shudra hai` that reverberated in Uttar Pradesh in 2023 while opposing the anti-shudra and anti-women narrative of Ramacharitamanas of Tulsidas has to become an all-India narrative. I hope this book gives enough impetus to future generations to carry the shudra/dalit/adivasi legacy forward consciously.

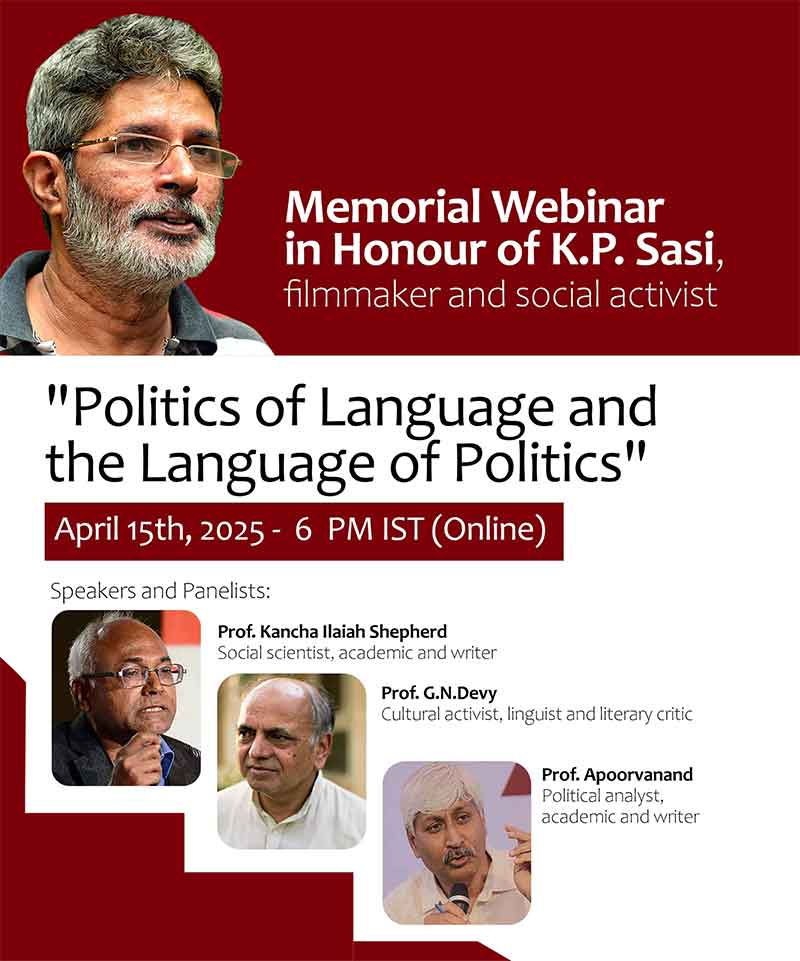

Kancha Ilaiah Shepherd is a political theorist, social activist and author.

You can order the book HERE