by Dr Shirin Akhter & Sachin N.

The University Grants Commission’s (UGC) Draft Guidelines and Draft Regulations on Minimum Qualifications, Recruitment, and Promotions (2025) are hurriedly being pushed as necessary compliance with short deadlines and smaller discussion windows. Any policy push, when rushed, gives a feeling of imposition and hidden implications. It is hence important to critically examine the impact of these guidelines on public-funded education, academic autonomy, faculty welfare, and their overall ideological imperative.

The New Education Policy 2020 has adopted Four Year Under Graduation (FYUG) and the first batch of these students will graduate only in 2026. Drafting higher education and research regulations without monitoring the implementation aspects and learning outcomes of the students under NEP FYUG looks academically unsound. This has already raised the concerns of the two crucial stakeholders, viz., teachers and students. Teachers are also agitated by the fact that these drafts have not been accompanied by the due UGC pay revision process as in the past.

Centralisation and the Erosion of Federalism

At the heart of these regulations lies a calculated attempt to dismantle the rights and powers of the elected governments in the states and replace them with the centre government-controlled gubernatorial architecture. The inclusion of a UGC nominee in the search committee for the Vice Chancellors comes off as a centralising move that interferes and curtails academic autonomy. Further, the guidelines empower Governors—who serve as Chancellors—to play a decisive role in the appointment of Vice-Chancellors, overriding the authority of state governments and search committees. This move has been widely opposed by opposition-ruled southern states, which recognise it as a blatant attempt by the BJP-led central government to control university administration and impose ideological hegemony. Even NDA allies have raised concerns over the centralisation of power in these Drafts.

The UGC, as per the 1956 Act, was envisaged as essentially a grants body supporting academic research and innovation in higher education that was also to set minimum standards for higher education institutions. Over the last decade, UGC’s role in disbursing educational grants to HEIs has been weakened by the adoption of loan-based funding (through HEFA) that is ruled by a market imperative, unlike the welfare motive of grants. At the same time, it has become more intrusive into the governance structures beyond its mandated domain with politically motivated interventions. UGC’s regulatory teeth are weaponised through the kind of policy overreach evident in the Drafts in question to undermine the concurrent nature of education in government policy.

The 42nd Constitutional Amendment in 1977 moved higher education from the State List to the Concurrent List, not the Union List. The central government has the authority only to coordinate and determine standards in institutions of higher education and research. The UGC regulations issued under the UGC Act, 1956, instead of complying with this constitutional mandate, attempt to usurp the powers of the states and impose a central control. This is the crisis of federalism in Indian education policymaking, hinting at the larger crisis of constitutional federalism in India.

As per Item 32 of the State List, the establishment and regulation of universities fall under the jurisdiction of the states. The universities in different states function according to the laws adopted by the respective state legislatures. They account for more than 40% of the total universities in India, while the central universities are only 5% of the total. The respective state governments bear approximately 80% of the financial burden of running the state universities. By claiming that UGC regulations supersede state laws, the central government is violating the constitutional division of powers, reducing universities to mere extensions of its authority. This move lacks constitutional probity and marks a fundamental shift towards an authoritarian education system, where universities function as compliant arms rather than as independent centres of learning and debate.

Coporatisation of Faculty: Overwork, Casualisation and Precarity

The new guidelines introduce structural changes that further degrade faculty working conditions and push academics into precarious, exploitative arrangements. The cadre ratio model (one Professor for every two Associate Professors and four Assistant Professors) ensures that permanent, senior faculty positions remain scarce, forcing younger academics into contractual employment. The mandatory eight-hour campus requirement treats faculty as factory workers, disregarding the realities of research, mentorship, and intellectual labour. Moreover, study leave—essential for academic growth—is now restricted to Assistant Professors, undermining opportunities for mid-career scholars to pursue research.

Under Clause 3.2, an academic irrationality that allows dilution of core competency and rigor in the chosen discipline of an academician is promoted. Here, the eligibility criteria for entry-level teaching positions have been changed to favourably accommodate NET/PhDs who don’t have the same academic domain in their earlier academic levels to be eligible for assistant professorship solely based on the subjects in which they obtain NET or PhD qualifications in the name of faux interdisciplinarity. Additionally, the evaluation criteria for recruitment and promotion under clause 3.8 of the Draft impose arbitrary and exclusionary conditions that reflect a corporate-style restructuring of faculty assessment. The requirement that faculty engage in consultancy, digital content creation, or startup development shifts the focus away from rigorous classroom pedagogy towards revenue generation. This approach disproportionately disadvantages scholars in the humanities and social sciences, whose research cannot be easily monetised through corporate sponsorship or technological innovation. One has to view the added criteria as paving the way for large-scale lateral entry of professors of practice (Clause 9) in jobs, i.e., to hire people outside academia through diluted recruitment norms and “notable contributions”, by which the provisions of social justice through job reservation will be compromised.

The most glaring problem is the replacement of traditional markers of academic excellence with neoliberal productivity metrics: ‘Research or Teaching Lab Development’ privileges STEM disciplines and discriminates against humanities and social science scholars; ‘Consultancy / Sponsored Research’ forces faculty to align their work with corporate and state interests, rather than independent inquiry; ‘Startup Development’ turns academics into entrepreneurs, undermining the fundamental role of universities as spaces for critical thinking. These criteria do not measure academic calibre; they merely reward those who can commodify their work, establish a hire and fire policy of insecurity, ensuring the dominance of market-driven priorities in higher education. This dilution of standards on the one hand and the embrace of corporate yardsticks on the other in recruitment and career advancement substantially devalue the existing classroom-teaching and research-centric approach while rewarding ideological allegiance and corporate governance in academics.

Marketisation and the Death of Public Knowledge

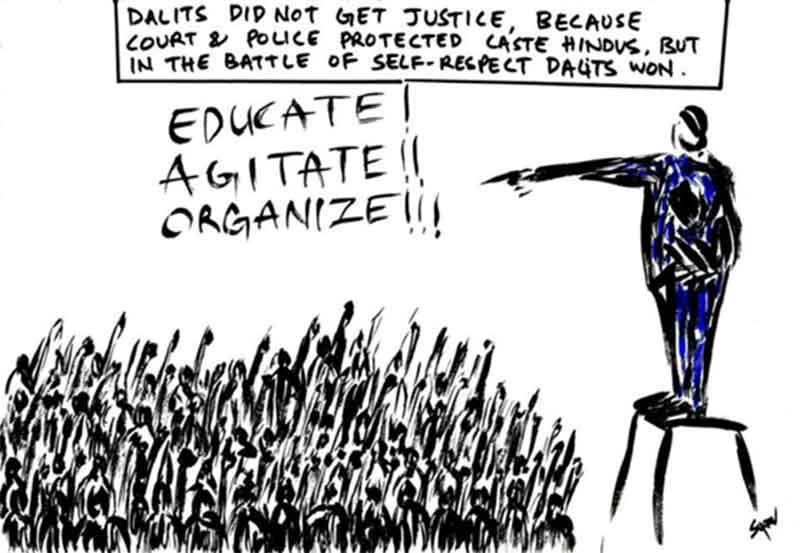

The UGC’s policies align with a broader neoliberal restructuring of higher education, where universities are transformed from public institutions into market-driven enterprises. The National Credit Framework (NCrF) prioritises skill-based, vocational training over critical, interdisciplinary education, reducing universities to job-training centres for the private sector. Research is no longer valued for its intellectual or social contributions; instead, faculty performance is judged based on patents, corporate-funded projects, and industry partnerships. Rising tuition fees and self-financing models further restrict access, disproportionately affecting Dalit, Bahujan, Adivasi (DBA) students and other marginalised groups. Higher education, once a vehicle for social mobility and knowledge production, is being reduced to a privilege reserved for an elite few.

The inclusion of ‘Digital Content Creation for MOOCs’ as a key performance metric under Clause 3.8 reflects this neoliberal capture of academia. MOOCs are not an educational innovation but a cost-cutting mechanism that allows universities to replace full-time faculty with prerecorded lectures. Faculty are expected to spend uncompensated labor creating content that will be exploited indefinitely by the university, mirroring the gig economy model that has already devastated employment in other sectors.

Authoritarianism and the Policing of Thought

For the first time, individuals outside the academia, i.e., from bureaucracy, corporate business, military forces, etc., may become VCs as per this draft (Clause 10.1). This may further institutionalize corporatism and censorship, as acceptance of divergent thoughts and opinions is often missing in these sectors, unlike the academia. Perhaps the most insidious aspect of the UGC’s guidelines is their explicit attempt to criminalise dissent and enforce ideological conformity. The newly introduced Code of Professional Ethics requires faculty to adhere to undefined “national ideals” and maintain “appropriate behaviour,” creating a bureaucratic mechanism to silence critical academics. In an environment where universities have already been branded “anti-national” for resisting state narratives, these regulations provide legal cover for the systematic persecution of dissenting scholars.

This ideological capture is also reinforced through the implicit insistence on an ‘Indian Knowledge System’ as a promoted benchmark for academic excellence. While research into traditional knowledge can be valuable, its umbrella deployment and phrasing invisibilises the diversity and pluralism in the systems of intellectual enquiry inherent to this land and its people and opens the door for further Hindutva infiltration in academic syllabi and institutional structures. The result is a homogenised, depoliticised education system where intellectual inquiry is replaced by ideological subservience to a political Hindutva in power.

The Struggle for Intellectual and Democratic Freedom

These policies represent an existential threat to intellectual freedom, social justice, academic pluralism, and the right to education. Teachers’ unions, student organisations, and state governments are actively opposing this corporate-Hindutva takeover of universities. Legal challenges could be mounted against the UGC’s unconstitutional overreach, asserting the authority of state governments in educational governance. Mass mobilisation is essential, bringing together faculty, students, and civil society in collective protest against the authoritarian measures to reverse the policy onslaught.

Education and the institutions imparting it are people’s window to the world. If these policies are implemented, Indian universities will no longer be spaces of critical thought but instruments of bureaucratic control, market exploitation, and ideological repression. The destruction of academic excellence, the suppression of independent thought, and the transformation of universities into ideological machines represent not just an education crisis but a democratic crisis. We must reject the corporatisation and ideological capture of education and reclaim higher learning as a radical, transformative, and socially relevant force. The future of an enlightened public, social justice, and intellectual freedom depends on it – all the reasons to resist and reject the Drafts and insist on a principled policy true to the ideals of the constitution.

Dr. Shirin Akhter is Associate Professor, Department of Economics, Zakir Husain Delhi College, University of Delhi.

Sachin N. is Associate Professor, Department of English, Dyal Singh College, University of Delhi.