Abstract

Introduction

Remembered histories make up our inner lives, and that of our families and communities. Happy and joyful memories, dimly-remembered and unexplained events as children have a way of inhabiting our lives in unexpected ways. Hence history, and memory, is also about us and others living together. Communities whose histories are neither written nor spoken are considered forgotten. The Dalit communities in India are said to be a people who have lost their histories. How then do they live? Have they really lost their histories? This paper is an attempt to explore answers to that question.

To start with, we will break up the ideas under Memory and Identity under several heads: History, Collective Memory, Identity, Culture, State Response, and Individual Voice/Consciousness.

History is defined as an academic and objective representation of the past. The very fact that it is defined as academic means that it is produced by persons outside of the events being recorded. The accounts of war are seldom written by the common soldier. It may be written by a general or a war historian and will contain details of the battles, the resources deployed, the territories lost or gained, lives lost, and the outcome in political, economic, and social terms, from the point of view of the writer of the account. This history will hardly record what went through the mind of the soldier in the trenches or in the front line : the fear, the chaos, the raw courage or the lack of it felt by the foot soldier. Even less, will it record the experiences of the civilians on whose land and farms the battles are fought. Those experiences may be recorded for posterity in the form of stories, poems, songs or just reminiscences shared by people who survived the events. But who will tell the stories of those who died in the war, either as participants or as innocent bystanders? Will their lives and understandings suffer erasure?

Collective Memory is what steps in at this juncture. It may be defined as a socially shared representation of the past that plays and integral role in maintaining the identity of the group. Thus, it fulfills where History fails. It reveals how groups interpret history, and in a very real sense the formal written history, the formal record, is an antithesis of Collective memory. The irony is that this formal written History is considered objective, whereas collective memory is seen as subjective.

Let us now compare and contrast the two:

Where Collective memory reflects a single committed perspective, the formal historical account may be distanced from any particular perspective.

Collective memory may reflect the experiences of a group, or their cultural framework, whereas the formal history may lack this record.

Colletive memory is unselfconscious in its expression, and impatient with ambiguities about the motives and interpretation, whereas the historical account will have a critical reflective stance, and recognises some ambiguities.

It may be helpful to study some examples of how this plays out in our world. Films, especially popular films, often influence the collective imagination very powerfully and have served as a means to attain popularity and even political power in several states especially in South India. In recent years, Hindi films have been a focus of controversy especially where they depict Historical figures like the Mughals, other kings, their wives, and so on. To cite just one example out of many, a film, Jodha Akbar, was released in 2008 and soon became the focus of much controversy.[1] Akbar is considered a secular icon and his marriage to a Rajput princess, Jodha was considered by folkloric accounts to be an example of communal harmony. However, in the present day, according to the report carried by Reuters,

Whether Emperor Akbar, a Muslim, married Hindu Rajput princess Jodhaa some 450 years ago is debated by historians, but the alliance has fed folklore of an enduring love in a country scarred by a history of religious bloodbaths.

Jodhaa Akbar”, which stars former Miss World Aishwarya Rai Bachchan, plays out the royal courtship to the backdrop of palace intrigues and epic battles.

Some Rajput groups attacked movie halls and tore posters of the film, saying it was historically inaccurate, and that Jodhaa was in fact Akbar’s daughter-in-law.

For fear of violent protests, the film was not released in Rajasthan — an important Bollywood market and the place where many Rajputs hail from.

Protesters disrupted a screening at a mall in Gurgaon, while a mob attacked a cinema hall in Ahmedabad, forcing multiplexes to temporarily close, the Press Trust of India reported.

Here is an example of how collective memory and Historical accounts can diverge and have varying impacts on society including triggering violence and arson.

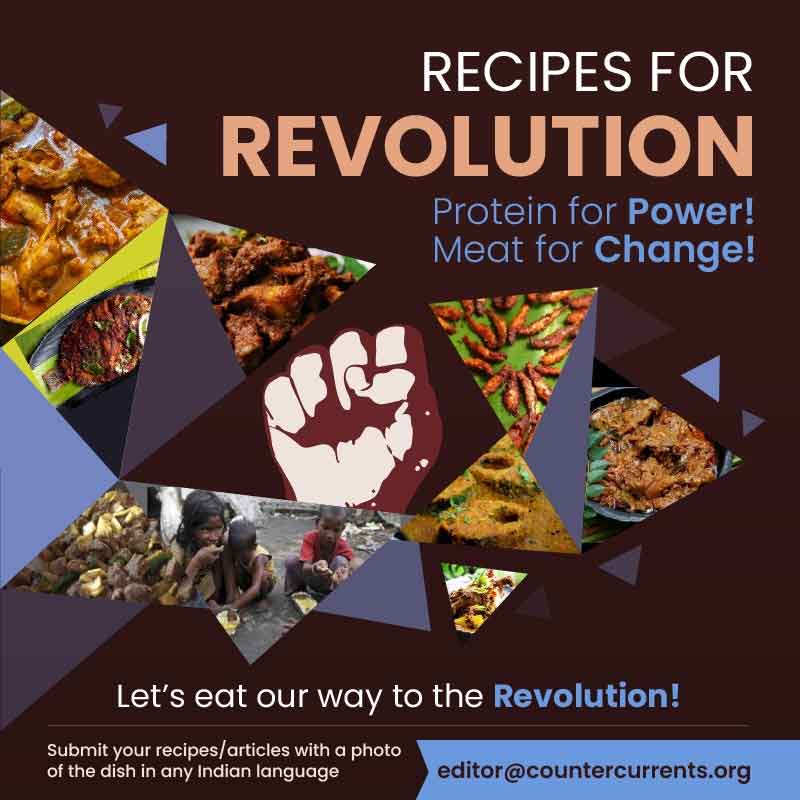

A more recent example is a Tamil film, Mamannan, by director Mari Selvaraj, which has been doing very well in the theatres. The film reflects a recent trend of films being made by Dalit directors and hence their depiction of Dalits is very different from the way in which mainstream films. While hitherto, audiences have seen them stereotyped as servile, untrustworthy, or as objects of hate or derision, Dalit directors are giving their depiction a make over which is closer to the reality: they are shown as full human beings with their own sense of agency.

Another example, closer home, is the textbooks controversy in Karnataka where the BJP government tried to rewrite the text books by removing references to Nehru, the first PM, and include biographies of controversial right-wing icons such as Savarkar and glorifying Nathuram Godse, the convicted assassin of Mahatma Gandhi, and vilifying Tippu Sultan. Needless to say, after the assembly elections, the newly elected government which defeated the BJP reversed the content and restored the earlier textbooks, which included references to Tippu Sultan as a freedom fighter who rebelled against the British.

Identity

The Issue of Identity could be very fraught in India, riven as it is with numerous layers of fragmentation in society, gender and class being only two layers. Caste, region, language, state, food habits, clothes, skin colour, appearance : there are any number of factors which can operate to create both a sense of community or a sense of alienation. In general, population of the less economically sound states, usually in the East, tend to migrate to the rest of the country to eke out fragile livelihoods in the cities of the South and North, and the fields and factories in Western India. Often these economic migrants, who in addition to being poor, could also belong to minorities like Adivasi, OBC, Dalit, or Muslim, thus making their lives in their place of work very risky and insecure. This is not only in the present day. Dr. BR Ambedkar, eminent constitutional lawyer, economist and thinker, writes in his introduction to an autobiographical account ‘Waiting for a Visa’[2], in which he relates various experiences of his life from childhood till he started working as a consultant to the Maharaja of Baroda, as well as including two telling instances of how untouchability took the life an innocent baby of a dalit man because the doctor refused to treat the newborn as she was “untouchable”, and another Dalit man who was harassed when he reported to duty in a government institution, so much so he had to leave the place and flee

Foreigners of course know of the existence of untouchability. But not being next door to it, so to say, they are unable to realise how oppressive it is in its actuality. It is difficult for them to understand how it is possible for a few untouchables to live on the edge of a village consisting of a large number of Hindus, go through the village daily to free it from the most disagreeable of its filth and to carry the errands of all the sundry, collect food at the doors of the Hindus, buy spices and oil at the shops of the Hindu Bania from a distance, regard the village in every way as their home, and yet never touch nor be touched by any one belonging to the village. The problem is how best to give an idea of the way the untouchables are treated by the caste Hindus. A general description or a record of cases of the treatment accorded to them are the two methods by which this purpose could be achieved. I have felt that the latter would be more effective than the former. In choosing these illustrations I have drawn partly upon my experience and partly upon the experience of others. I begin with events that have happened to me in my own life.

I have explored the issue of Identity from a gender and marginalised lens more fully in an article, “India, the Idea of Nation and the Subaltern Indian Woman”[3] I quote:

Writers such as Bankim Chandra wrote several novels which captured the popular imagination and his poems, especially “Vande Mataram”, a hymn in praise/worship of the Motherland, here depicted as a verdant fertile land, yielding much fruit, pure and glowing with light, adorned with fragrant flowers. This image of the land as a goddess became the order of the day. Depictions of the map of the country, with J&K as the crowned head of the goddess, the Southern Peninsula as the lower part of the body, adorned with the sari, Gujarat being the right arm, holding the palm out in benediction came quickly. From there, to depict Mother India – Bharat Mata riding on a Lion as the incarnation of the Divine Female, Durga or Shakti – was just a flourish of the artist’s paintbrush. As this image was part of the popular religious imagination of the politically powerful East of India, and as Calcutta was at the time an important political and economic capital, this image became the dominant “popular” visual representation of the aspiration of the people of India.

In the article, I go on to show how this is contrasted with the lived realities of the women from the marginalised sections, who tend to be very stressed and deprived of basic necessities of daily life like water, food, and even security of life and limb, living lives of deprivation and poverty for generations,and treated as less than human and untouchables, whereas the Idea of India as a nation is typified as the imagination of an uppercaste male, which casts the country as a woman who is “Sujalam, Suphalam, Malayaja Sheetalam” : verdant, fertile, cool, beautiful.

Culture

One of the most powerful drivers of identity is Culture. According to Wikipedia

“Over the centuries, there has been a significant fusion of cultures between Buddhists, Hindus, Muslims, Jains, Sikhs and various tribal populations in India. India is the birthplace of ….Buddhism, Jainism, Sikhism, and other religions. They are collectively known as Indian religions…

India is also the home of numerous folk and indigenous belief systems and faith practices. There have been Jews on Indian soil since the time of King Solomon (circa 900 BC). There are historical evidences to show that Thomas the apostle of Jesus travelled to India in 52 AD, and brought the faith of Jesus with him. He was martyred in Mylapore near present day Chennai in 72 AD. Hence Christianity is also areligion of great antiquity in India. India’s west coast had trade relations with the Arabs even from the time of Kind David, in 1100 AD, and continued down the centuries. When Islam spread among the Arabs, it found its way to Indian shores: [4]

Even before the life of Prophet Muhammad (Peace Be Upon Him) in the 600s, Arab traders were in contact with India. Merchants would regularly sail to the west coast of India to trade goods such as spices, gold, and African goods. Naturally, when the Arabs began to convert to Islam, they carried their new religion to the shores of India. The first mosque of India, the Cheraman Juma Masjid, was built in 629 (during the life of Prophet Muhammad) in Kerala, by the first Muslim from India, Cheraman Perumal Bhaskara Ravi Varma. Through continued trade between Arab Muslims and Indians, Islam continued to spread in coastal Indian cities and towns, both through immigration and conversion.

Thus the culture of India is a rich amalgam of faith, Belief, food, clothes, and since it is a vast subcontinent with every kind of terrain from the highest of mountains to the driest of deserts, a coastline of several thousand kilometres, and mountains and rivers, with forests which vary widely in the kind of trees, plants, animals, birds, fish and flora, and produce a bewildering array of plant-related foods, medicines, spices, and other useful products the diversity in the food, clothing, language, architecture, and cultural art forms are probably the most diverse in the world. It was home to over 1700 spoken languages, and at the present time, statistics show that there are approximately 122 major languages spoken in India. Moreover, there are more than 1500 other languages or dialects that also exist in India as the mother tongue of various populations. The literature both oral and written is so vast. The oral literature continues in many remote populations since most of these languages lack a script. There are 22 official languages in India, which do have scripts. In some cases the scripts of the locally dominant language is used to write, for instance Konkani, spoken all along the western coast, lacks its own script and is written in the Kannada, Roman and Devanagari script depending on the area which the users live, and is also found in several dialects.

Like Religion, language is an important cultural marker and is often a flash point in India. In South India for instance there is widespread opposition to the use of Hindi because of the large numbers of local languages in south India whose speakers naturally believe here. In the case of the indigenous populations, there are a large number of spoken dialects which richly reflect their cultural diversity and worldview. In an India which is carved up into linguistic states, there are many subcultures in each state with numerous languages. Hence the dominant language can also be seen and experienced as a socially hegemonic factor. In such a context, the numerically smaller communities with their own language, namely the adivasis and Dalits, find it difficult to hold their own. Also among them are the artisanal castes, now called the backward classes. All three categories now constitute the Bahujans[5] communities in India. The problem of access to education for these groups is much compounded by the language issue. Since most of them speak languages without scripts, and the formal government schools run in the medium of the dominant groups in the state, there are many challenges. This is over and above the traditional ban on education for the marginalised and oppressed groups, based on the ideology of caste and discrimination based on one’s caste identity. Ironically, in India the school system is one of the sites of the replication of caste in society, as we will see further into this paper.

Cultural Appropriation by Elite capture of performative arts

However, the Dalit-Bahujans continue to face the loss of and appropriation of their cultural productions and artefacts. One of the most blatant and flagrant such appropriations is of their music and dance forms. What is now considered the acme of Indian classical dance, the Bharatanatyam, was actually, as late as the 1950s, a dance form known as Sadir, which was performed by non-brahmin women in temples in South India, primarily Tamil Nadu, accompanied by the men on several traditional wind and percussion instruments. In fact there is a caste known as Isai Vellalar – Isai meaning Music, and Vellalar the name of a sudra caste. The temple dancers were dedicated to the temples as girls and devoted their lives to this art form. In the early years of Independence, and eminent social and political activist, Dr. Muthulakshmi Reddy, herself a daughter of a devadasi, initiated legislation to end the practice of the dedication of dancers to the temples in the Madras Presidency as early as the 1930s but faced a lot of opposition from both the public and the devadasis themselves. Ultimately the legislation was passed in the Tamil Nadu assembly in 1956.

Around the same time there was a move by another cultural activist, Rukminidevi Arundale[6], to promote the dance form, by performing it for an audience of upper-class /castes. She was herself from a progressive Brahmin family and was married to a white man, George Arundale, who was closely associated with Anne Besant and her Theosophical Society, which was active internationally and was very influential in India at the time. Annie Besant and another of her close associates, AO Hume were instrumental in starting the Indian National Congress and gave the call for “Home Rule”. Thus Rukminidevi had socio-cultural capital which she used to “redeem” Sadir from its “ill-reputed” roots which were linked with temple prostitution and “elevated” it to represent high art which depicted the relationship of the devotee to the Divine in Navarasas[7] or nine expressions/emotions. Along with them the entire presentation, including stagecraft, costumes, music, the relationship with the accompanists… everything passed into the hands of the elites, and a “classical” dance was born, right within living memory. The centre for dance called Kalaniketan, started in the 30s, moved to its present location in the 60s, and is a cultural complex with courses in dance, music, and also has a weaving centre which produces handloom sarees which are used by the students in their dance productions.

The traditional practitioners of the form are now completely isolated and alienated from the entire machinery of dance and cultural representation. In very recent years, one woman, Nritya Pillai, from the Isai Vellalar caste, has attempted to raise her voice against this appropriation and writes and speaks on the subject extensively.[8]

The Untouchables and Cultural Revolt

As seen above, the untouchables have traditionally been excluded from literacy and education in a cultural context which criminalises the education of those from the fourth varna, the Sudras and below them, the untouchables, now called the Dalits. It is for this reason that in recent years Dalits are asserting the need for the study of English by their children to counter the marginalisation that they face in society. Since they are thinly distributed across the country and also speak different languages and have varying traditionally mandated occupations, it is a matter of both common sense and pragmatism to study English which gives them the ability to interact with the world of education, professions, employment, trade, and business, arenas which were denied to them for centuries on account of their social exclusion from education and employment due to casteist mindsets of people in society.

However, the oppressed people did not all take it lying down. The earliest critiques of caste and Brahminism in modern times came from Jotirao Phule, from the backward Mali caste in Pune, who was among the first young men to get access to English education and was powerfully impacted by Thomas Paine’s “Rights of Man”. Phule and his equally illustrious wife, Savitribai, were the first to start formal schools for the girls of all communities in India, and as such are the pioneers in the emancipation of women in India, among many other path-breaking initiatives undertaken by them to improve the lot of the Bahujans, or Shudra-ati-shudras as he termed them

Jotirao Phule never wavered in his quest for truth and justice. The later generations took considerable time to understand and appreciate the profound significance of his unflinching espousal of the ‘rights of man’ which remained till the end of his life a major theme of his writings and a goal of his actions.’ Jotirao Phule also know as ‘Krantisurya’ was the first activist, writer, thinker, social reformer and revolutionary of non- Brahmin community of modern India. Phule was firm in his belief that the emancipation of the women, Shudras and ati-Sudras could be achieved only through the total annihilation of the Brahmanical culture system. Therefore in leading the low caste protest movement, he put himself outside the Brahmanical culture system and sought to create a counter-culture based on truth, justice and humanity,’ which he advocated in his work Sarvajanik Satya Dharma.[9]

On Phule’s life and work, Eminent Scholar of anti-Caste movements in India, Dr. Gail Omvedt, says[10]

Jyotirao Phule represented a very different set of interests and a very different outlook on India from all the upper caste elite thinkers of the so-called Indian Renaissance who have dominated the awareness of both Indian and foreign intellectuals. The elite expressed an ideology of what may be described as the “national revolution;” it was the nationalism of a class combining bourgeois and high caste traditions. Phule represented the ideology of the social revolution in its earliest form, with a peasant and anti-caste outlook.

….

Any culture rests upon a class society and the dominance of a particular class. In India, Hindu culture and the caste system rested upon Brahmanism; hence Phule linked his thought with a movement of opposition to the Brahman elite. “Non-Brahmanism”, therefore, represented not simply communalism or a result of British divide-and-rule policies; it represented the fi first expression of social revolution. (Omvedt 1971: 1969)

Jyotirao Phule represented a very different set of interests and a very different outlook on India from all the upper caste elite thinkers of the so-called Indian Renaissance who have dominated the awareness of both Indian and foreign intellectuals. The elite expressed an ideology of what may be described as the “national revolution;” it was the nationalism of a class combining bourgeois and high caste traditions. Phule represented the ideology of the social revolution in its earliest form, with a peasant and anti-caste outlook. ….Any culture rests upon a class society and the dominance of a particular class. In India, Hindu culture and the caste system rested upon Brahmanism; hence Phule linked his thought with a movement of opposition to the Brahman elite. “Non-Brahmanism”, therefore, represented not simply communalism or a result of British divide-and-rule policies; it represented the first expression of social revolution. (Omvedt 1971: 1969)

Dr. BR Ambedkar, the eminent jurist, economist and polymath, also the chief architect of the Indian Constitution was inspired by Phule’s life and work. His extensive research and writings on caste, economics and law continue to be influential both in scholarship and public policy right down into the present day. Ambedkar too was from an untouchable caste and despite being from a relatively affluent background due to his father’s employment in the British Army, was subject to much caste humiliation in school and in fact even well after he qualified as a lawyer and had two doctorates, one in economics and another in Law. He was also an eminent scholar of religion and towards the end of his life, after extensive study of religion, decided to convert to Buddhism. His research shows how Buddhism was itself a revolt against the social stratification of the citizens that was prevalent in Buddha’s time. The Buddha’s impact was such that the Sangha was the equal space where all were welcome and were treated with equal regard. Even women found their place in sanghas, something the traditional practices denied them. Thus on 14th October 1956 he converted in a public ceremony in Nagpur at a ground now known as Dheekshabhoomi, and then proceeded to oversee the conversion of about 500,000 of his followers to Buddhism immediately after. This was a clear and public revolt by the Dalits against the brahminical practice of untouchability and caste discrimination.

Sumeet Samos: A Case Study

Sumeet Samos, s young scholar and cultural activist from the Dom Community in Odisha, wrote an autobiographical account[11] of how language, culture and education played out in his life, while also exploring the historical and sociological roots of his community. His community speaks Dom, and his remote village was such that they didn’t even hear Odia, the language of his state, being spoken. In a review of his book[12], carried in Scroll.in, the online news portal, the reviewer says:

Most scholarship on Dalits has typically reduced the burden of caste to their abjection and poverty, or it has fetishised their historical suffering for an upper-caste readership. Samos is interested in turning away from this anthropological gaze, and refers to himself as a “participant observer”, interlacing moments in the contemporary political history of Odisha with episodes of his life.

Steeped in the history and cultural politics of the Desia land, Samos traces the consolidation of local Brahminical identities from the reign of the Suryavanshi dynasty of the 15th century, the migration of upper-caste Hindus from coastal Odisha in the twentieth century, and the generation of Komatis who arrived after the Srikakulam rebellion of the ’70s. Samos clarifies that a Desiaidentity is primarily linguistic; it is referred to as the motherland of several communities, but is never personified with the same nationalist figures like Bharat Mata.

But the local government primary school taught in the Odia medium and had lessons steeped in mainstream Odia culture, very alien to their own lives. As a child, his family was the only one which followed the Christian faith in their Dom settlement, which was right opposite the town’s cremation ground. As children, they were witness to the almost daily cremations of corpses. Since their people were traditionally mandated to work in the cremation grounds, they were the most despised among the various dalit communities. But his grandfather was an itinerant seller of bangles and also the composer of many songs. In the course of his travels someone gave him a Bible, which carried home and placed on the shelf where there were other objects of worship. It lay there forgotten till one day there was a fire which razed the settlement. Only their house was saved. His elders then interpreted this to mean that the Bible had some power to save lives, and then it was opened and his father, then a young man, began to read. He had studied up to high school and was literate in Odia. Thus he discovered the God of the Bible, and began to live by it.[13]

He found a small but regular job in a nearby town and was able to ensure that his two children could go to school. Sumeet’s mother was also employed as a village health worker and served the community around her in the area of health – conducting home based deliveries, issuing basic medicines, etc. This family’s lived example, and his parents’ leadership brought a small praying community together which slowly grew and began to attract more and more young people into itself. This was an organic faith which was not mediated by any missionary work or any intervention from outside – no sops, no clergy. They worshipped singing songs they composed in their own language. There was no pastor or priest, only Sumeet’s father taught them what he learned from reading the Word. His mother led the group in prayers, and continues to have an active mentoring role with generations of their community even now. There were no rice bags or school admissions involved!

Who tells such stories of the people who live forgotten in remote locations? But this story written in English by a young person whose father put him in an English medium school, the only rural dalit boy in the school – he faced endless teasing and torture by his fellow hostellers, but refused to complain either to his parents or the school authorities. He knew that if he was taken out from there he would lose his chance to go out into the world. He applied himself to his lessons and excelled not only in studies but in extra-curricular activities like elocution and debate, and soon made a mark at the district level, winning prizes in these contests. He tried to find ways to earn some money and bought English guides and books in the town nearby and tried his best to practice speaking and reading in English. Eventually he finished well in his 12th, and even won a place in a central engineering college in South India, but found that he couldn’t manage to survive with the lack of resources and social support.

He went back, studied a BA, moved to Delhi to find what he could do next. Someone known to him was in JNU and he heard about its fee structure and academics, and took the tough entrance and passed, completed his masters in Spanish language and then, for reasons of caste discrimination couldn’t get into the MPhil course of his choice. This was the time when JNU was in ferment due to a number of cases, the Rohith Vemula agitations, the ECC, and the JNU’s admin harassment of students for scholarships etc was at its peak.

It was around this time that he discovered that he could compose and sing rap songs. He began to rap in the protest meetings, and his compositions ranged from Dom to Hindi to English. They brought him instant fame, since the news media covered the agitations. He began to receive invitations from young people in campuses across the country. Staff from a French radio station invited him to join their promotional tours in France and soon his rapping went international too!

He wanted to go for higher studies but as a result of the punitive measures by the university against those who had agitated, his marks transcripts were badly delayed but ultimately they were released. He applied for and got a place in Oxford University for an MPhil course. The fees were completely out of his reach and he went for crowdfunding the 36 lakhs he required. He was able to reach his target funding support within a few days! He completed his course and returned to India, and soon was able to publish his remarkable memoirs while still in his 20s. He credits his parents, their faith and hard work, and the family’s faith in God for the extraordinary twists and turns his life took in the face of almost unimaginable odds. Their example has now opened the way for many of the young people in the Dom community to look for opportunities for education and employment, where earlier they only could think of daily wage work in nearby towns. Several have gone on to study in Universities, even prestigious ones like JNU. Many girls have taken up studies in nursing and started working in up-market hospitals in cities far afield like Bangalore.

State Response to the Caste system

The young Indian state attempted to birth a brave new world with the mottos of Liberty, Equality and Fraternity, as stated in the Preamble to the Indian Constitution, clearly the imprint of the Liberal values of its architect Dr. BR Ambedkar. While the Indian state has attempted to correct the wrongs of historical and traditional caste discrimination by providing reparations in the form of reservations in education, jobs and democratic representation, the implementation of these and other protective and progressive legislations have suffered by a complete lack of political will to implement them in letter and spirit.

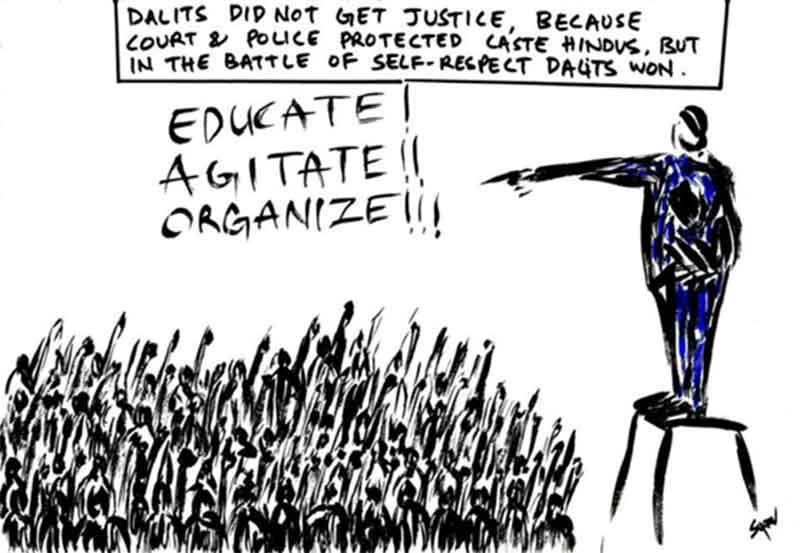

On the contrary, one continues to see disturbing social trends in which the bahujans are continued to be oppressed in increasing ways, even for such trivialities as men growing moustaches, wearing fashionable clothes like jeans and shades, riding motorbikes, etc. Dalits continue to live in segregated settlements, and are subjected to serious destructive attacks on their dwellings and posessions, and the poisoning of their water sources : major hate crimes which recur even in the present day, all over the country. Political mobilisation, education, jobs : nothing seems to make a dent in the stubborn persistence of caste hate in society. It is becoming increasingly common to see that young couples especially where the male is a dalit or bahujan, being killed for daring to cross caste boundaries to love and marry.

Any assertion by Dalits is put down with a firm hand, even by the state machinery. One of the most glaring examples is that of the 16 people who were arrested and some of them incarcerated without charge for several years after a public meeting, the Elgar Parishad, on the eve of an annual celebration at the site of the Bhima Koregaon monument, which was put up to commemorate the defeat of the oppressive Peshwa regime in Maharashtra by a very small contingent comprising of mercenaries mostly from bahujan communities. The year 2017 was the 200th anniversary of the Battle of Bhima Koregaon. More details on this are found in this recent update in the Mint.[14]

The lives of the Dalit women are in a category of their own. They are subject to all forms of violence, exclusion and deprivation but continue to display remarkable courage, resourcefulness and humanity in the face of these oppressive systems. For more on this topic, please read my article Feminism and Dalit women in India at

https://www.countercurrents.org/stephen161109.htm

Sumeet’s story while unique in many ways, is repeated in the lives of many young bahujans though the exact details may vary. Thus the struggle to transcend the disadvantages of birth and caste continues into the present day and will continue into the future as well, as long as political and religious ideologies continue to promote unfreedoms and consequently inequality for certain sections in society.

Cynthia Stephen is an Independent Social Policy Researcher

Paper presented at Dharmaram Vidya Kshetram’s Conference : Dialogue and Solidarity A Religio-Subaltern Perspective 24th – 27th November 2022

[1] https://www.reuters.com/article/idINIndia-32007720080218

[2] http://www.ambedkar.org/ambcd/53.%20Waiting%20For%20A%20Visa.htm

[3] https://www.countercurrents.org/cynthia150811.htm

[4] https://www.islamicity.org/11485/how-islam-spread-in-india/

[5] Bahujan is a Pali term frequently found in Buddhist texts, with a literal meaning of “the many”, or “the majority”. In a modern context, it refers to the combined population of the Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes, Other Backward Classes, Muslims, and minorities, who together constitute the demographic majority of India.

[6] https://kalakshetra.in/the-founder/

[7] The Navarasa, in the scriptures refer to the nine expressions that humans often show. These are love (shringaara), laughter (haasya), kind-heartedness or compassion (karuna), anger (roudra), courage (veera), fear (bhayaanaka), disgust (bheebhatsya), wonder or surprise (adbhutha) and peace or tranquility (shaantha).

[8] https://feminisminindia.com/2021/03/25/nrithya-pillai-interview-bharatanatyam-isai-vellalar/

[9] MAHATMA JYOTIRAO PHULE’S VIEWS ON UPLIFTMENT OF WOMEN AS REFLECTED IN SARVAJANIK SATYADHARMA

Shiladhar Yallappa Mugali and Priyadarshini Sharanappa Amadihal, available at https://www.jstor.org/stable/44147232

[10] Cited in https://www.researchgate.net/publication/354373961_Gail_Omvedt_1941-2021_A_Scholar_Activist_an_Activist_Scholar

[11] Sumeet Samos, Affairs of Caste, Panther’s Paw Publications, 2022

[13] This writer’s personal conversations with Sumeet Samos

[14]https://www.livemint.com/news/india/bhima-koregaon-elgaar-parishad-case-16-arrested-1-died-in-custody-some-got-bail-a-2023-update-11690537456618.html