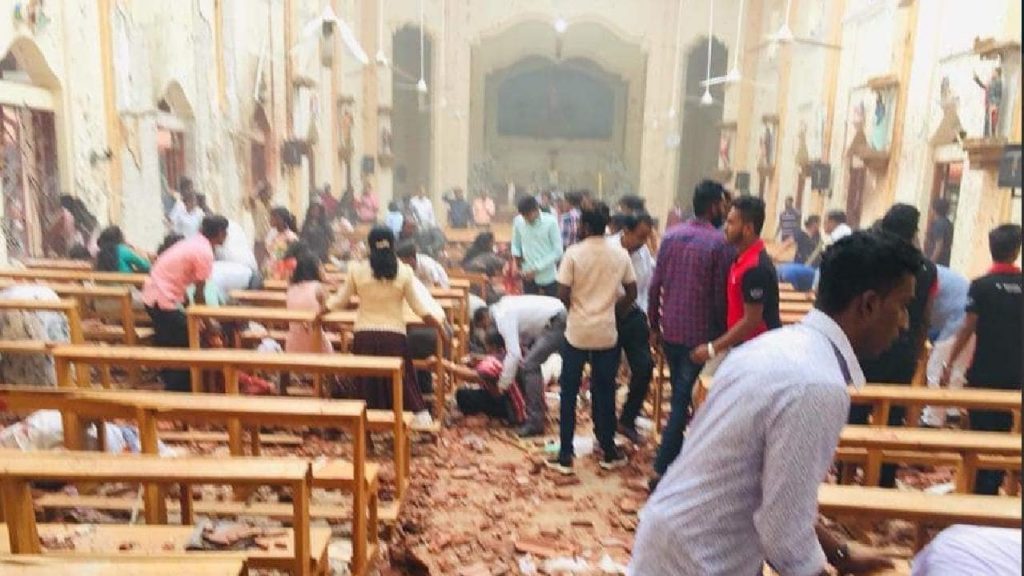

A series of coordinated bombings struck three churches and three hotels on Easter Sunday killing 207 people in the worst attacks in Sri Lanka since the end of the civil war 10 years ago.

At least 450 people were wounded in total of eight explosions. According to police several of the attacks were carried out by suicide bombers.

Most of the victims were killed in three churches where worshippers were attending Easter Sunday services.

Washington Post said: “the suicide bombings on the holiest day of the Christian calendar, when churches see their highest attendance of the year, were widely viewed as targeting Sri Lanka’s small Christian community, a minority that regularly faces discrimination.”

Fewer than 8 percent of the roughly 20 million people in Sri Lanka are Christian (the vast majority of them Roman Catholic). Seventy percent are Buddhist, according to the country’s 2012 census, 12.6 percent are Hindu and 9.7 percent are Muslim.

Violent attacks on this scale against churches are without precedent in Sri Lanka. The Christian minority, however, does face violence and discrimination, the Washington Post added and quoted human rights activist Ruki Fernando as saying:

“Church services across the country have faced some sort of disruption in each of the past 11 Sundays. Last year, the National Christian Evangelical Alliance of Sri Lanka reported 86 verifiable cases of discrimination, threats and violence against Christians. Before Sunday’s attacks, 26 such incidents had occurred this year, including the disruption of a Sunday service by Buddhist monks.”

Radical Buddhism opposes converts

To borrow Open Doors USA, those who convert to Christianity from a Buddhist or Hindu background suffer the strongest forms of persecution. They are subject to harassment, discrimination and marginalization by family and community. These believers are pressured to recant Christianity; conversion is regarded as betrayal. All ethnic Sinhalese (the majority in Sri Lanka) are expected to be Buddhist.

Similarly, within the minority Tamil population in the northeast, Sinhalese are expected to be Hindu. Non-traditional churches are frequently targeted by neighbors, often joined by Buddhist monks and local officials, who demand Christians close their church buildings regarded as illegal.

Open Doors USA report pointed out that on September 9, 2018, a group of about 100 people stopped the worship service of a church at Beliatta, Hambantota District. They damaged a window, two motorcycles parked outside, and removed religious symbols hanging on the front door. Some forcibly entered the premises and threatened to kill the pastor and his family and demanded they stop gathering people for worship activities and leave the village.

The majority of state schools do not teach Christianity as a subject, and so Christian schoolchildren are forced to study Buddhism or Hinduism. There have also been reports that children were forced to participate in Buddhist rituals.

According to the National Christian Evangelical Alliance of Sri Lanka (NCEASL), there has been a sharp increase of attacks on Christians, including violent attacks often carried out through mobs.

Attacks on Christian churches resumed in May 2009

Tisaranee Gunasekara, a Colombo-based political commentator based in Colombo, following the 2009 victory over the LTTE (Tamil Tigers), attacks on Christian churches resumed in May 2009. “Unlike during the previous occasions, this time only evangelical churches were targeted. Days after the war ended, security forces raided the office of the National Christian Evangelical Alliance of Sri Lanka in Colombo. Since the raid was not linked to any further action, it seems that its purpose was to terrorise. An attack on a church in the suburban town of Kelaniya was personally led by a government minister closely identified with the ruling family. As attacks on evangelical churches intensified, Cardinal Malcolm Ranjith issued a statement blaming the victimized evangelicals of trying to convert Buddhists and Catholics. He was moved to protest only when a statue of the Virgin Mary, built to commemorate the 150th anniversary of a Catholic church in the provincial town of Avissawella, was burnt in late January 2013.”

Minorities are essentially outsiders, irrespective of how long they have been here. Sinhala-Buddhists are the sole owners of the country; minorities are not co-owners but guests, here on sufferance without inalienable rights, notwithstanding what the Constitution might proclaim, argues Tisaranee Gunasekara.

“The ideological underpinning for this host and guest concept is provided by the Mahawamsa, the 6th-century chronicle written by a Buddhist monk. The Mahawamsa claims that the Buddha, on his deathbed, proclaimed Lanka the Buddhist Holy-Land: “In Lanka, O lord of gods, will my religion be established, therefore carefully protect…Lanka.”

“It is from these ancient myths of a chosen people and a sinless war that the modern Sinhala-Buddhist supremacists fashion their version of ‘the clash of civilisations.’ In this rendition, pioneered by Anagarika Dharmapala (whose anti-minority diatribes played a role in the 1915 riots) ‘Sinhala Buddhist’ Lanka is forever threatened by ‘Christian, Islamic and Hindu worlds’. Minorities are inherently suspect as they can be the agents of these inimical external forces. Since geographical displacement is not possible, the only solution is to confine minorities to their ‘rightful’ place politically. This should be done legislatively and peacefully, if possible, and violently, if necessary, the logic goes,” Gunasekara concludes.

The Muslim connection or Muslimphobia

But the Christian community isn’t alone in being targeted in Sri Lanka. The Muslim minority, too, is persecuted. In 2013, a Buddhist mob attacked a mosque in Colombo, injuring 12, according to Washington Post.

Amarnath Amarasingam, a senior research fellow at the Institute for Strategic Dialogue, was quoted by Washington Post as saying that rumors of radicalization of Muslims and of extremist groups tied to outside funding have been used as an excuse by some in the majority to attack Muslims.

Not surprisingly, a top police official reportedly alerted security officials in an advisory 10 days ago about a threat to churches from a radical Islamist group, National Thowheeth Jama’ath. “But it was unclear what safeguards, if any, were taken, or if in the end the group played any role in the violence. And on Sunday, reflecting frictions within the government, the prime minister pointedly said he had not been informed,” according to New York Times which published a picture of the advisory.

Sri Lankan Muslims: the new ‘others’

Writing under the title Sri Lankan Muslims: the new others, Tisaranee Gunasekara digs into the history and politics of Muslimphobia in Sri Lanka.

“Lankan Muslims are not demanding a separate state. There’s no armed Muslim militancy. The two communities have historically lived in peace, with a few exceptions such as the 1915 riots. The Muslim community sided with the Sinhala majority and the Lankan state during the long Eelam War, especially after the forced eviction of Muslims from the North by the LTTE. Nor are Muslims trying to convert Buddhists, a charge that is usually levelled against religious minorities,” Gunasekara said adding:

“So where did the fear and the hate come from? Was it born naturally or engineered artificially? It is easy to blame power-hungry politicians for sowing racial/religious hatred, but the truth is more complicated. There seem to be enough ordinary Sinhala-Buddhists out there who are on the lookout for enemies. Facts don’t interest them, slogans suffice. As a result there is always a ready-made audience for ethno-religious fear-mongering.”

Gunasekara believes that the reason there is focus on Muslims which he calls new Tamils, because the Tamils are too beaten down to amount to a serious threat?

Civilisational angst and the search for enemies

Gunasekara further elaborates:

“The first post-independence attempts at depicting Muslims as an existential threat to Sinhala-Buddhists began in the late 1990’s. It’s architect was Gangodawila Soma Thero, a Buddhist monk who was a hugely popular preacher. By this time, the riots of 1915 constituted a footnote in history rather than a living memory. If Muslimphobia existed in the collective psyche of the Sinhalese, it was too marginal to be a political factor.

“But Soma Thero succeeded in creating a wave of anti-Muslim hysteria, and rendering it acceptable to middle and upper echelons of Sinhala society. He convinced educated middle-class Sinhalese (many of them professionals) that Muslims were a greater threat to Sinhalese than even the LTTE. He preached about a Muslim plan to overtake Sinhalese demographically. Others joined in, especially the then secretary and current leader of the JHU (National Heritage Party then going by the name of Sinhala Urumaya) Champaka Ranawaka. Ranawaka who claimed that Muslims were trying to carve out a separate state in the Eastern Province called Nasiristan. That first round of anti-Muslim hysteria led to an outburst of anti-Muslim violence in the town of Mawanella in 2001.

“Soma Thero’s Muslim baiting came to an end abruptly when he was deemed the loser in a TV debate with M H M Ashraff, the leader of the Sri Lanka Muslims Congress. In the widely watched debate, Ashraff debunked the accusations against Muslims one by one; he also displayed his superior knowledge of Buddhist scriptures. Soon after this debacle, Soma Thero abandoned Muslimphobia and moved on, with seamless ease, to Christianophobia. His followers followed suit en masse and with hardly a question.

So Muslims were allowed to recede into the background and Christians became Sinhala-Buddhism’s new ‘enemy.’ They were accused of trying to turn Sri Lanka into a Christian country through mass conversions. Statistics were bandied, maps produced and a Western conspiracy was alleged. Churches were attacked and a draconian anti-conversion bill placed on the political agenda. When Soma Thero died suddenly during a trip to Russia, fundamentalist Christians were blamed for killing him. The outcry was such that the government was forced to appoint a commission to study the matter (the monk had travelled to St. Petersburg in December without any winter gear and died of exposure).

The first reported attack on Muslims

The first reported attack on Muslims, post-victory, took place in September 2011, when a mob demolished a small mosque in Anuradhapura. This was decried by the government. Other than a few incidents, there was no special targeting of Muslims during this period, not even by the BBS (Bodu Bala Sena – Buddhist Power Force) whose members have more recently been held responsible for instigating anti-Muslim violence. When the BBS held its first public convention in Colombo in 2012, none of its five demands were aimed at Muslims exclusively.

The depiction of Muslims as the new enemy commenced in February 2013. The BBS held a mass rally in the suburban town of Maharagama and unveiled a national campaign against the labelling of food as halal. Until then few Buddhists had been bothered about the labelling; overnight, it became a matter of utmost importance to Sinhala-Buddhism. Around the same time, Muslim shop owners in two provincial towns claimed that they were sent letters demanding their shops be closed.

The freedom accorded to the BBS and its fellow travellers indicated that they had the blessings of the Rajapaksa family. This connection became public when Gotabhaya Rajapaksa, the powerful younger brother of then-President Mahinda Rajapaksa, attended a BBS function. He praised the monks for engaging in a “nationally important task”, and insisted that they should not be feared or doubted by anyone.

Less than a month after this Rajapaksa endorsement, the suburban branch of Fashion Bug, a clothing chain owned by Muslims was burnt by a mob.

The Rajapaksas regarded anti-minority phobia as a way of gaining and maintaining Sinhala-Buddhist support in the context of a worsening economic crisis. But their ploy didn’t work. The Rajapaksas lost both the presidential and parliamentary elections of 2015, partly because a segment of the Sinhala-Buddhist electorate shifted to the opposition. The reasons for this crucial shift included economic hardships and anger at blatant corruption and nepotism. If the rise of the Rajapaksas indicated the political potency of Sinhala-Buddhist supremacism, their unexpected electoral fall highlighted the limits of that strategy.

In April 2012, a mob attacked a mosque in the heritage city of Dambulla. In 2013, as anti-Muslim hysteria was reaching its zenith.

The current political conjuncture is characterized by growing economic hardships, a government unwilling to stand up to extremists, and an opposition ready to use anti-minority hysteria to regain power. If these three conditions remain unchanged, the March 2018 anti-Muslim attacks in Kandy will be the beginning of a new cycle of violence and possibly counter-violence. In Sri Lanka, the past is once again set to defeat the future, concluded Tisaranee Gunasekara.

Abdus Sattar Ghazali is the Chief Editor of the Journal of America (www.journalofamerica.net) email: asghazali2011 (@) gmail.com