Satyajit Ray’s film is a heady cocktail of dystopia and comic fantasy

Eleven years after Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne (‘The Adventures of Goopy and Bagha’) came its sequel, Hirak Rajar Deshe (‘The Kingdom of Diamonds’), in December, 1980. In the interregnum, Satyajit Ray had made eight full-length feature films, one television short and three documentaries, and the genres these offerings ranged over included period/historical film, crime thriller, contemporary social commentary and intimate family drama. The 1970s were probably a more restless and turbulent period than any other in post-independence India, punctuated as they were by massive rural and urban discontent, the Bangladesh War and the gigantic problem of refuges it brought in its wake, the Naxalite movement, Indira Gandhi’s Emergency and a severely repressive state machinery ruling many provinces of the Indian Union including Ray’s own West Bengal. Things had begun to quieten down somewhat by 1980, democracy appeared to have reasserted its hold over public life once again, and in Kolkata the Left Front, having been voted into power in 1977, was legislating wide-ranging land reforms and riding the crest of popular support. A second musical to pick up the threads from where Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne had left off seemed appropriate at that stage.

But Hirak Rajar Deshe is a different kind of musical to Goopy Gyne…, for it contains the distilled essence of some of the themes that animated the other Ray films of the 1970s: corruption, injustice, cynicism and the mislaying of the moral compass. In the process, it moves away from the charmed world of two simple-minded young men and their uproariously funny exploits to step into the dreary and grim world of a despotic king. Indeed, it comes closest to being what we can call a political film, for it makes several fairly unambiguous statements about how unbridled political power systematically undermines basic human freedoms, foists its own opportunistic narratives of life and choice upon communities, and corrupts lives and minds irretrievably. Satyajit Ray himself appeared to think of Jana Aranya (‘The Middleman’—1975/76) as the film making the most forthright political statements – presumably about all-encompassing corruption in mid-1970s India – but that only goes to show that a great artist is not necessarily the best judge of his own work. The statements that Hirak Rajar Deshe makes hit home with far greater directness than any conveyed by any other film of Ray’s, made before it or after. Some of these remain as valid today as they were then. Some, indeed, anticipate later developments with startling clarity, and this is one of the film’s great achievements.

Thus, the evil king decides to shut down all the schools in his kingdom, because “the more they (i.e., the students) study, the more they get to know, and the less they tend to obey”. The crusade against education is invested with snappy slogans designed to capture the popular imagination. The age-old Bengali aphorism which translates roughly into “Those who study hard// Are sure to ride in plush cars” transmogrifies, under the new order, into “Those who study hard// Are sure to starve and die”. (The Bengali epigrams used in the film are rhyming couplets, and when delivered in a sing-song voice, in the manner of the pundit in the king’s court, they sound both funny and pertinent.) The king also loves to hear this chant: “Don’t get upset if you are starving// For you’ll grow fat if you’re eating too much”. Another favourite quip, a reliable antidote against the sinister effect books can have on people, is: “There is no limit to how much there is to know// So it is pointless to try and know anything”. From here, the burning of books is but a short step, and the king’s stormtroopers make a triumphal bonfire of books and manuscripts in the courtyard of the schoolteacher’s house.

Science has also gifted the king a macabre instrument of coercion: the brain-washing machine, a terrifying contraption that wipes the human brain clean of all that it held before and supplants it with sanctimonious homilies embedded in the machine, so that the victim goes on parroting those chants –and them alone – endlessly. Thus the poor farmer, after he has been put through the machine, babbles, “It is never a good idea // To fall behind on taxes.// Even if we were to starve // We mustn’t be late with our payments”. The mantra for the miner – who slaves away in the king’s diamond mines for a pittance of a wage – goes: “He who toils inside the mines// Is thrice accursed, so bear this in mind”. Together, these images of the manipulation of the human mind serve as a powerful allegory of a totalitarian regime run amok — indeed of a fascist state.

They also set off eerie echoes from post-2014 India, when the clamour for closing down universities and throttling dissent rises more steeply each day. The Diamond king’s loathing of free thought finds a close parallel in the pronounced anti-intellectualism of India’s current rulers, also in their anxiety to rewrite text books wholesale. In a graphic sequence, when poor men’s hovels are torn down by the king’s militia because they might be an eyesore to the king’s foreign guests, it is impossible to miss the overtones of the big slum clean-up saga that played out in Gujarat prior to Donald Trump’s visit in February this year.

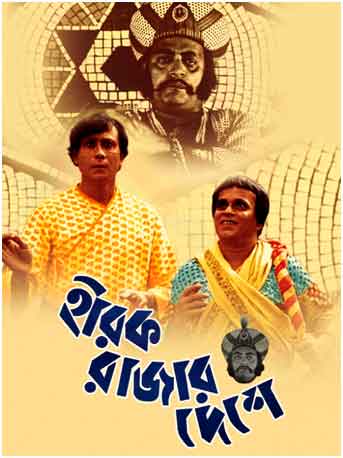

Just as the cynical regimentation of social life feeds into the king’s megalomania, so does the harvest of the diamond mines fatten his pelf. The film unerringly foregrounds these linkages between different kinds of exploitation, economic, emotional and intellectual. The moral degeneracy of the court is complete with the ministers behaving exactly like the king’s courtiers, nodding all the time like mannequins, and drooling over the king’s occasional gift of a precious stone. The film was conceived as a comic fantasy, and this allows Ray to stretch credulity to the limit, as when the king himself, brainwashed at his own diabolical machine, joins hands with the revolutionaries to topple his own gigantic statue, thus ushering in a new order. Here Ray abandons his political messaging and embraces make-believe once again. Even though Soumitra Chatterjee is nominally the film’s hero and does his usual competent job of it, it is Utpal Dutt as the evil king – a role combining the dictator’s brutality with the vulnerability of a pathologically insecure man – who produces the film’s stand-out performance. A full forty years after its release, Hirak Rajar Deshe has not dated yet.

Anjan Basu can be reached at [email protected]

SIGN UP FOR COUNTERCURRENTS DAILY NEWS LETTER