Africa’s 1.3 billion people remain “extremely vulnerable” as the continent warms more, and at a faster rate, than the global average, warns the UN. Yet Africa’s 54 countries are responsible for less than 4% of global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions.

In State of the Climate in Africa 2020 (https://library.wmo.int/doc_num.php?explnum_id=10833), a new report from the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) and other agencies, released ahead of the UN climate conference in Scotland that starts October 31, reminds the grim fact.

More than 100 million extremely poor people in Africa are threatened by accelerating climate change that could also melt away the continent’s few glaciers within two decades, warned the UN report on Tuesday.

In the report, the UN highlighted Africa’s “disproportionate vulnerability” last year from food insecurity, poverty and population displacement.

“By 2030, it is estimated that up to 118 million extremely poor people will be exposed to drought, floods and extreme heat in Africa, if adequate response measures are not put in place,” said Josefa Leonel Correia Sacko, commissioner for rural economy and agriculture at the African Union Commission.

The extremely poor are those who live on less than $1.90 per day, according to the UN report coordinated by the WMO.

“In sub-Saharan Africa, climate change could further lower gross domestic product by up to three percent by 2050,” Sacko said in the foreword to the report.

“Not only are physical conditions getting worse, but also the number of people being affected is increasing,” she said.

Citing the Global Report on Food Crises of the World Food Programme, the WMO report said: In 2020, approximately 98 million people suffered from acute food insecurity and needed humanitarian assistance in Africa, which is an almost 40% increase from 2019.

The report said: In 2020, the number of severely food-insecure people in the Democratic Republic of the Congo continued to increase, with up to 21.8 million. In Nigeria, food insecurity levels reached the highest on record, with approximately 9.2 million in IPC Phase 3 or above.

WMO Secretary-General Petteri Taalas said that last year Africa saw temperatures continue to increase, “accelerating sea-level rise”, as well as extreme weather events like floods, landslides and droughts, all indicators of climate change.

The report said: Ethiopia and Somalia were the countries most affected by desert locusts and which experienced the highest associated crop and pasture losses. In 2020, Ethiopia lost an estimated 356 286 tons of cereal, affecting about 806 400 farming households, 197,163 hectares of cropland and 1.35 million hectares of pasture and browse.

It said: In the first six months of 2020, the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre recorded 14.6 million new displacements across 127 countries and territories; conflict and violence accounted for approximately 4.8 million and disasters 9.8 million. Approximately 12% of all new displacements worldwide occurred in the East and Horn of Africa region, with over 1.2 million new disaster-related displacements and almost 500,000 new conflict-related displacements.

Concerning extreme precipitation events, 146 mm of rain was recorded in 24 hours in Jijel, Algeria, on 21 December 2020, which contributed to a lot of damage to infrastructure.

In Morocco, dry conditions persisted from September 2019 to May/June 2020, and the rainy season was one of the four driest years since 1981.

Anomalies of monthly mean temperature reached +3.5 °C in Algeria and +4.0 °C in Morocco. In July, it was very hot in Morocco and Algeria, with temperatures reaching or even exceeding 48 °C in the majority of the southern regions of Algeria (the Sahara); 47.8 °C in Hassi Messaoud and Ouargla; and 48.5 °C in Adrar.

In Tunisia, 2020 was the third hottest year since 1950, after 2016 and 2014, with an average temperature of 20.2 °C and a positive anomaly of 0.9 °C.

In Morocco, tornadoes, which have been observed in recent years, continued to be reported, although with no known damage.

Tripoli, Libya, was affected by severe weather conditions on 27 October 2020.27 The winds ahead of the trough, which strengthened with height, favored organized convective storms including rotating and supercell storms which produced exceptionally large giant hailstones of about 20 cm in diameter.

Disappearing Glaciers

“The rapid shrinking of the last remaining glaciers in eastern Africa, which are expected to melt entirely in the near future, signals the threat of imminent and irreversible change to the Earth system,” Taalas said.

Last year, Africa’s land mass and waters warmed more rapidly than the world average, the report said.

The 30-year warming trend from 1991-2020 was above that of the 1961-1990 period in all of Africa’s regions and “significantly higher” than for the trend for 1931-1960.

The rate in sea level rise along the tropical coasts and the south Atlantic, as well as along the Indian Ocean, was higher than the world average.

Though too small to serve as significant water reserves, Africa’s glaciers have high tourism and scientific value and yet are retreating at a rate higher than the global average.

“If this continues, it will lead to total deglaciation by the 2040s,” the report said.

“Mount Kenya is expected to be deglaciated a decade sooner, which will make it one of the first entire mountain ranges to lose glaciers due to human-induced climate change.”

The other glaciers in Africa are on the Rwenzori Mountains in Uganda and Mount Kilimanjaro in Tanzania.

To avoid even higher costs of disaster relief, the WMO urged African countries to invest in “hydrometeorological infrastructure and early warning systems to prepare for escalating high-impact hazardous events.”

It backed broadening access to early warning systems and to information on food prices and weather, including with simple text or voice messages informing farmers when to plant, irrigate or fertilise.

“Rapid implementation of African adaptation strategies will spur economic development and generate more jobs in support of economic recovery from the Covid-19 pandemic,” the report said.

The report involved the WMO, the African Union Commission, the Economic Commission for Africa (ECA) through the Africa Climate Policy Centre (ACPC), international and regional scientific organisations and UN agencies.

The latest report on the state of Africa’s climate by the WMO and African Union agencies paints a dire picture of the continent’s ability to adapt to increasingly frequent weather disasters.

The report says last year was Africa’s third warmest on record, according to one set of data, 0.86 degrees Celsius above the average in the three decades leading to 2010. It has mostly warmed slower than high-latitude temperate zones, but the impact is still devastating.

The report came as African countries demanded a new system to track funding from wealthy nations that are failing to meet a $100-billion annual target to help the developing world tackle climate change.

The demand by Africa’s top climate negotiator Tanguy Gahouma, ahead of the COP26 climate summit, highlights tensions between the world’s 20 largest economies that produce more than three quarters of GHG emissions, and developing countries that are bearing the brunt of global warming.

Africa has long been feared to be severely impacted by climate change. Its croplands are already drought-prone, many of its major cities hug the coast, and widespread poverty makes it harder for people to adapt.

Apart from worsening drought on a continent heavily reliant on agriculture, there was extensive flooding in East and West Africa in 2020, the report noted, while a locust infestation of historic proportions, which began a year earlier, continued to wreak havoc.

The report estimated that sub-Saharan Africa would need to spend $30-$50 billion, or 2-3% of GDP, each year on adaptation to avert even worse consequences.

An estimated 1.2 million people were displaced by storms and floods in 2020, nearly two and half times as many people as fled their homes because of conflict in the same year.

Roughly 12% of all new population displacements on the planet happen in East Africa and the Horn of Africa region, about two-thirds of them because of drought, flood, or other climate and disaster-related reasons, the WMO said.

Massive displacement, hunger and increasing climate shocks such droughts and flooding are in the future, and yet the lack of climate data in parts of Africa “is having a major impact” on disaster warnings for millions of people, WMO Secretary-General Petteri Taalas said at Tuesday’s launch.

Already, the UN has warned that the Indian Ocean island nation of Madagascar is one where “famine-like conditions have been driven by climate change.” And it says parts of South Sudan are seeing the worst flooding in almost 60 years.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) has done household surveys in Ethiopia, Malawi, and Tanzania, as well as the Sahel nations of Mali and Niger. They reveal that, among other things, better access to climate and weather data is needed to help the primarily smallholder farmers of Africa practice “smart” agriculture. This access has the potential to significantly reduce the risk of food insecurity.

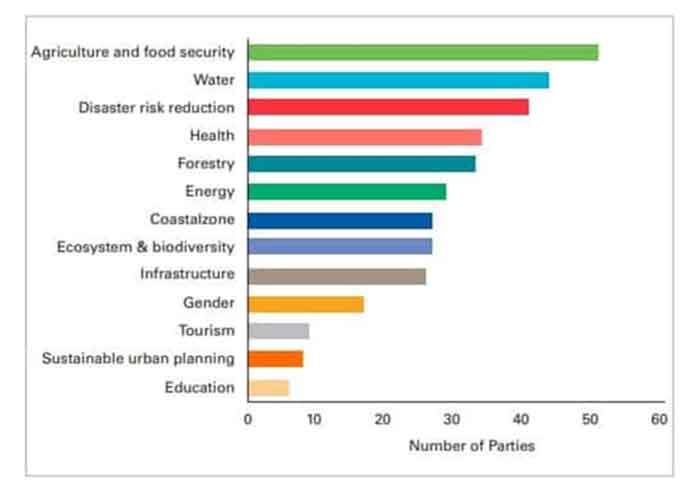

Priority areas for adaptation for the African Region. Source: WMO analysis of the NDCs of 53 countries in Africa.

Yet nearly all African nations – it is 92%, according to the WMO – lack the training and technology needed to deliver these services. Data on weather, climate patterns and water resources is limited, as is the expertise to provide them. Many of the systems used to communicate early warnings and other information are obsolete.

Despite the threats ahead to the African continent, the voices of Africans have been less represented than richer regions at global climate meetings and among the authors of the crucial Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change scientific assessments. African participation in IPCC reports has been “extremely low,” according to Future Climate for Africa, a multi-country research program.

The costs ahead are huge. “Overall, Africa will need investments of over $3 trillion in mitigation and adaptation by 2030 to implement its (national climate plans), requiring significant, accessible and predictable inflows of conditional finance,” the WMO’s Taalas said.

“The cost of adapting to climate change in Africa will rise to $50 billion per year by 2050, even assuming the international efforts to keep global warming below 2 degrees Celsius.”

Key Messages of the Report

- The warming trend for 1991–2020 was higher than for the 1961–1990 period in all African subregions and significantly higher than the trend for 1931–1960.

- Annual average temperatures in 2020 across the continent were above the 1981–2010 average in most areas. The largest temperature anomalies were recorded in the north-west of the continent, in western equatorial areas and in parts of the Greater Horn of Africa.

- The rates of sea-level rise along the tropical and South Atlantic coasts and Indian Ocean coast are higher than the global mean rate, at approximately 3.6 mm/yr and 4.1 mm/yr, respectively. Sea levels along the Mediterranean coasts are rising at a rate that is approximately 2.9 mm/yr lower than the global mean.

- The current retreat rates of the African mountain glaciers are higher than the global mean and if this continues will lead to total deglaciation by the 2040s. Mount Kenya is expected to be deglaciated a decade sooner, which will make it one of the first entire mountain ranges to lose glaciers due to anthropogenic climate change.

- Higher-than-normal precipitation predominated in the Sahel, the Rift Valley, the central Nile catchment and north-eastern Africa, the Kalahari basin and the lower course of the Congo River. Dry conditions prevailed along the south-eastern part of the continent, in Madagascar, in the northern coast of the Gulf of Guinea and in north-western Africa.

- The compounded effects of protracted conflicts, political instability, climate variability, pest outbreaks and economic crises, exacerbated by the impacts of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic, were the key drivers of a significant increase in food insecurity.

- Food insecurity increases by 5–20 percentage points with each flood or drought in sub-Saharan Africa. Associated deterioration in health and in children’s school attendance can worsen longer-term income and gender inequalities. In 2020, there was an almost 40% increase in population affected by food insecurity compared with the previous year.

- An estimated 12% of all new population displacements worldwide occurred in the East and Horn of Africa region, with over 1.2 million new disaster-related displacements and almost 500 000 new conflict-related displacements. Floods and storms contributed the most to internal disaster-related displacement, followed by droughts.

- In sub-Saharan Africa, adaptation costs are estimated at US$ 30–50 billion (2–3% of regional gross domestic product (GDP)) each year over the next decade, to avoid even higher costs of additional disaster relief. Climate-resilient development in Africa requires investments in hydrometeorological infrastructure and early warning systems to prepare for escalating high-impact hazardous events.

- Household surveys by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in Ethiopia, Malawi, Mali, the Niger and the United Republic of Tanzania found, among other factors, that broadening access to early warning systems and to information on food prices and weather (even with simple text or voice messages to inform farmers on when to plant, irrigate or fertilize, enabling climate-smart agriculture) has the potential to reduce the chance of food insecurity by 30 percentage points.

- Rapid implementation of African adaptation strategies will spur economic development and generate more jobs in support of economic recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic. Pursuing the common priorities identified by the African Union Green Recovery Action Plan would facilitate the achievement of the continent’s sustainable and green recovery from the pandemic while also enabling effective climate action.

Africa Calls for Climate Finance Tracker

African countries want a new system to track funding from wealthy nations that are failing to meet a $100-billion annual target to help the developing world tackle climate change, Africa’s lead climate negotiator said.

The demand highlights tensions ahead of the COP26 climate summit between the world’s 20 largest economies, which are behind 80% of GHG emissions, and developing countries that are bearing the brunt of the effects of global warming.

“If we prove that someone is responsible for something, it is his responsibility to pay for that,” said Tanguy Gahouma, chair of the African Group of Negotiators at COP26, the UN climate summit in Glasgow, Scotland, which starts on Oct. 31.

In 2009, developed countries agreed to raise $100 billion per year by 2020 to help the developing world deal with the fallout from a warming planet.

The latest available estimates from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) show this funding hit $79.6 billion in 2019, just 2% more than in 2018.

The OECD data shows Asian countries on average received 43% of the climate finance in 2016-19, while Africa received 26%. Gahouma said a more detailed shared system was needed that would keep tabs on each country’s contribution and where it went on the ground.

“They say they achieved maybe 70% of the target, but we cannot see that,” Gahouma said.

“We need to have a clear roadmap how they will put on the table the $100 billion per year, how we can track (it),” he said in an interview on Thursday. “We do not have time to lose and Africa is one of the most vulnerable regions of the world.”

Even as wealthy nations miss the $100 billion target, African countries plan to push for this funding to be scaled up more than tenfold by 2030.

“The $100 billion was a political commitment. It was not based on the real needs of developing countries to tackle climate change,” Gahouma said.

World leaders and their representatives have just a few days at the summit in Glasgow to try to broker deals to cut emissions faster and finance measures to adapt to climate pressures.

African countries face an extra challenge at the talks because administrative hurdles to entering Britain and to travelling during the coronavirus pandemic mean smaller than usual delegations can attend, Gahouma said.

“Limited delegations, with a very huge amount of work and limited time. This will be very challenging,” Gahouma said.