The La Niña, a natural cycle marked by cooler-than-average ocean water in the central Pacific Ocean, is back, U.S. federal forecasters announced Thursday. It is happening for the second straight year.

The La Niña (Spanish for “little girl”) climate pattern is one of the main drivers of weather around the world, especially during the late fall, winter and early spring.

It is the opposite of the more well-known El Niño pattern, which occurs when ocean temperatures are warmer than average.

Much of both southeast Asia and northern Australia are wetter in La Nina — and that is already apparent in Indonesia, Halpert said. Central Africa and southeast China tend to be drier.

Expect it to be cooler in western Canada, southern Alaska, Japan, the Korean peninsula, western Africa and southeastern Brazil.

“La Niña is anticipated to affect temperature and precipitation across the United States during the upcoming months,” forecasters from the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) Climate Prediction Center said Thursday.

“La Niña conditions have developed and are expected to continue with an 87% chance of La Niña in December 2021-February 2022,” the NOAA said in an advisory.

NOAA said this year’s La Niña probably will persist through the winter.

“Everything you want to see in having a La Niña we are seeing,” Michelle L’Heureux, a forecaster at the center, told Bloomberg News. “We are pretty confident La Niña is here.”

A typical La Niña winter in the U.S. brings rain and snow to the Northwest and unusually dry conditions to most of the southern tier of the U.S., according to the prediction center. The Southeast and mid-Atlantic also tend to see warmer-than-average temperatures during a La Niña winter.

Because of La Niña, California may see little relief from its drought, which will make its wildfire season even worse, Bloomberg said.

“Our scientists have been tracking the potential development of a La Niña since this summer, and it was a factor in the above-normal hurricane season forecast, which we have seen unfold,” said Mike Halpert, deputy director of NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center.

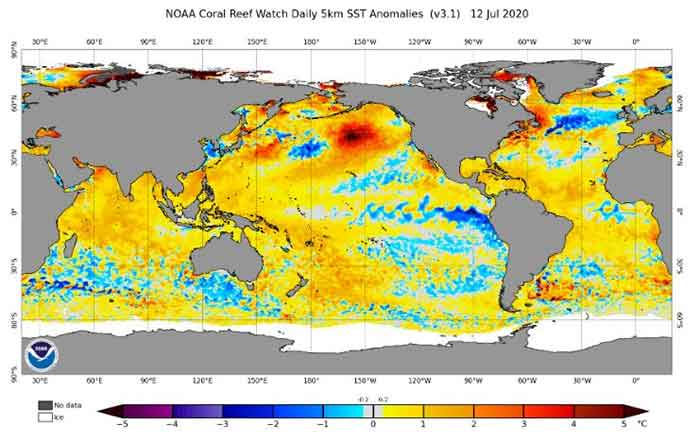

This is what a La Niña looks like: Cooler-than-average sea surface temperatures along the equator is indicative of La Niña in the tropical Pacific Ocean in September 2021.

Consecutive La Niñas are not uncommon and can be referred to as a “double dip.” In 2020, La Niña developed in August and dissipated in April 2021 as “ENSO-neutral” conditions returned.

The entire natural climate cycle of El Niño and La Niña is officially known by climate scientists as El Niño – Southern Oscillation (ENSO), a seesaw dance of warmer and cooler seawater in the central Pacific Ocean.

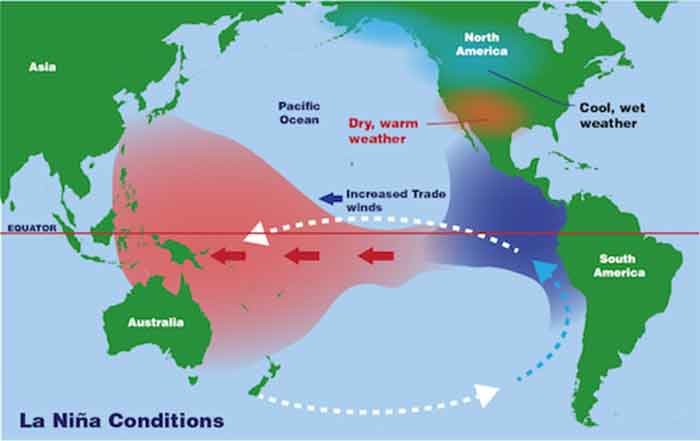

During La Niña events, trade winds are even stronger than usual, pushing more warm water toward Asia, NOAA said. Off the west coast of the Americas, upwelling increases, bringing cold, nutrient-rich water to the surface.

The weather system could intensify the worst effects of the drought that much of the region already finds itself in, including higher wildfire risks and water shortages through 2022.

La Niña is a climate pattern that usually delivers more dry days across the southern third of the U.S. Its drought-producing effects are especially pronounced in the south-west, but the phenomenon will also contribute to higher risks of hurricanes as the winds help the storms build.

The pattern has the potential to affect both precipitation and temperatures through early spring of next year. While the system was always associated with above average temperatures across the southern tier of the U.S., scientists have seen that pattern of warmer temperatures expand north. “Clearly climate change is a separate influence but it is modifying the impact we get with La Niña,” said Michelle L’Heureux.

To scientists, La Niña did not come as a surprise, since it occurred last year and tends to persist for as long as two years. It began forming in July this year, and NOAA scientists started to see the conditions develop over the past month. This week they issued an advisory noting a 90% likelihood that the system will affect winter weather across the US.

La Niña is characterized by colder-than-average sea surface levels in the Pacific Ocean near the equator. “[It] reorganizes tropical heat and tropical rainfall on such a large scale that it impacts the jetstream over the North Pacific Ocean and has downstream impacts over North America,” L’Heureux told the Guardian.

During La Niña years, winds push warm water west. This causes a churn that brings the frigid waters from the depths to the surface off the coast of South America. When the ocean’s temperature changes – even just a few degrees – the way it interacts with the atmosphere changes too and this can affect weather all around the world, as rain clouds form over warm patches of the ocean.

Different regions in the U.S. will experience different outcomes. Washington State, Oregon and possibly northern California could see wetter conditions than normal, possibly causing problems if the rain comes as a deluge.

“A lot of times when we talk about whether it was a wet year or dry year, you average the whole season,” said John Fasullo, a scientist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR). “But with climate change, you have greater amounts of rainfall being delivered in shorter bursts.”

In areas near fire footprints or regions that have been affected by drought, the topsoil is not able to absorb heavy rains, especially after plants, whose roots helped hold the soil in place, perish. “Short intense rainfall events can actually be a negative and damaging event,” he said, adding that climate change has produced a “multiplying effect”.

The weather system could also intensify the worst effects of the drought much of the U.S. west is already experiencing, including higher wildfire risks and water shortages through 2022.

“The warming of the climate has led to the drying of the southwest, so when you do have reduced rainfall the droughts get even worse and more intense,” said Fasullo, noting that a lack of precipitation is only one part of the problem.

Hotter temperatures and longer, larger, heatwaves bake even more moisture out of the environment. Warmth also works to deplete the snowpack – a vital water resource that feeds streams, rivers, and reservoirs.

Currently, 93% of the west is mired in drought conditions according to the U.S. Drought Monitor, with close to 60% of the region in extreme or exceptional drought. Scientists with the U.S. National Weather Service’s climate prediction center have said that much of the western region is so dry that it would require “sustained above-normal precipitation for several weeks for meaningful improvements.”

Still, La Niña is more of an indication of what to expect rather than a guarantee about what will happen in the coming months. “It can be overblown,” Fasullo said, “and each event has its own particular flavor in a given year.” Other factors influence rainfall patterns and there’s been lots of variation with this phenomenon in years past.

Park Williams, a climate scientist and professor at University of California, Los Angeles, said although La Niña could mean a higher likelihood the south-west will stay dry, it may not have as much of an impact on other areas. “The relationship between La Niña and drought across the Sierra Nevada and the upper Colorado River Basin has been extremely weak historically,” he said.

While it is still unclear just how dire the dearth of rainfall will be, Williams said there is no question climate change will continue to pose problems for the region. “As long as greenhouse gases continue to accumulate in the atmosphere,” he said, “the dice are loaded toward increasingly warmer temperatures, meaning less mountain snowpack, greater spring evaporation, and more intense summer heatwaves and wildfire activity.”

Just five months after the end of a La Nina that started in September 2020, the U.S. NOAA announced a new cooling of the Pacific is underway.

La Nina’s natural cooling of parts of the Pacific is the flip side of a warmer El Nino pattern and sets in motion changes to the world’s weather for months and sometimes years. But the changes vary from place to place and aren’t certainties, just tendencies.

La Ninas tend to cause more agricultural and drought damage to the U.S. than El Ninos and neutral conditions, according to a 1999 study. That study found La Ninas in general cause $2.2 billion to $6.5 billion in damage to the U.S. agriculture.

There is a 57% chance this will be a moderate La Nina and only 15% that it will be strong, said Mike Halpert, deputy director of NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center. He said it is unlikely to be as strong as last year’s because the second year of back-to-back La Ninas usually does not quite measure up to the first.

During last year’s La Nina, the Atlantic set a record with 30 named storms. This year, without La Nina, the season has still been busier than normal with 20 named storms and only one name left unused on the primary storm name list: Wanda.

La Ninas tend to make Atlantic seasons more active because one key ingredient in formation of storms is winds near the top of them. An El Nino triggers more crosswinds that decapitate storms, while a La Nina has fewer crosswinds, allowing storms to develop and grow.

Canada

The La Niña to impact Canada’s winter and the finale of the Atlantic hurricane season.

Last year’s La Niña lays the groundwork for this year’s to possibly act in a more traditional La Niña pattern.

The cold signal La Niña brings in from the central Pacific tends to induce an amplified Pacific jetstream, an important weather factor for Canada’s west coast. A changeable pattern and a northward shift in pacific storm paths likely to head towards B.C. Therefore, La Niña hints at a wet pattern for most of B.C.’s southern coast.

The amplified jetstream La Niña brings, also tends to focus the cold in the west and central areas of Canada. We may expect the focus of winter’s consistent cold temperatures in the west and Prairies, as cold arctic air funnels south through deep troughs.

A deep western trough is often counteracted by a deep eastern ridge, and we can expect a battle between the strength of the two over the Great Lakes, though only time will tell which will be the dominant winter weather driver.

If the eastern ridge fights back, Ontario, Quebec and Atlantic Canada could see prolonged fairer temperatures. Although, it only takes one round won by the cold arctic trough to funnel in the ingredients necessary for snowy, wet signals across the great lakes.

Ontario and Quebec will have to monitor multiple favourable storm paths. Colorado lows and lake-effect snowfall, driven by the contrast between cold air and relatively warmer water temperature of the Great Lakes, which may tick up the moisture signal above average.

Atlantic Canada should continue its watch for a couple more tropical storms to develop. Historically, La Niña phases are a factor that contributes to more active tropical storms in the Atlantic Ocean, by creating an environment with low shear and warmer Atlantic Ocean waters that drive storm development.

However, this driver tends to act more in the heart of hurricane season. We are now nearing November, our last tropical storm inning, with our main pitcher out and looking for energy deep in our bullpen.

Do not rule out a few more tropical systems developing, but also do not expect a superstar performance from La Niña this late in the game.

Combining all of this into a tropical storm season end and beginning of winter outlook, we can expect above-average rainfall on the west coast and great lakes, potentially in Atlantic Canada if favorable tropical storm paths develop, and a colder than average winter across the Prairies.