While observing the 50th anniversary of the Chipko movement for saving forests many inspiring stories were related but we did not hear much about the highly inspiring Appiko movement of Karnataka and some other parts of South India.

As this writer has visited some of these villages let me try to fill in this gap here, even though some time has passed since my two visits to these villages.

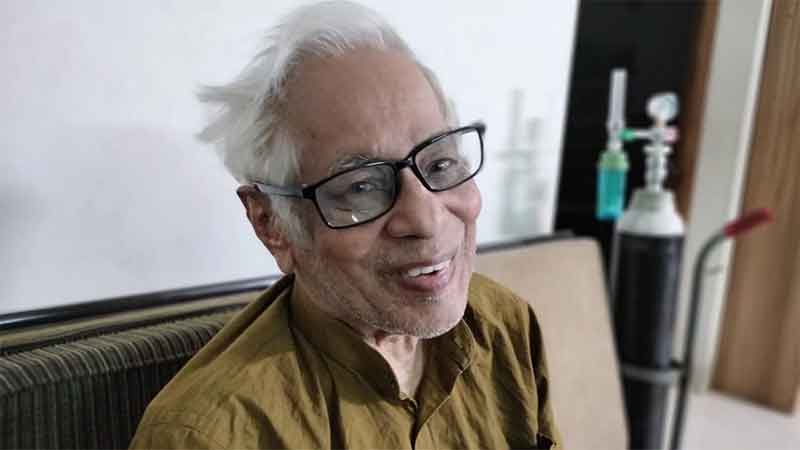

Although many persons, particularly villagers, contributed so much to this collective effort, the most central and pioneering contribution was no doubt made by Pandurang Hegde. I met him when he was still a student of the Delhi School of Social work. I had gone to the ashram established by Vimla and Sunderlal Bahuguna in Silyara village of Tehri Garhwal district of Uttarakhand to stay there for some days while researching a book on Chipko movement. It is here that I was fortunate to meet and befriend Pandurang, one of the finest activists and human beings I have met.

Although he had come to learn about Chipko movement as a student he was already on very comradely terms with senior activists. He soon passed out from the university as a gold medallist and took up a few jobs here and there to pay back his loans. However his heart was set in going back to his home district Uttar Kannada. Whatever he saw and learnt in the company of Himalayan Chipko activists he took very soon to these villages. As Sunderlal Ji said, the Himalayan bird flew over to the Western Ghats.

There are some parts in the world – although these are getting increasingly rarer- where the existence of forests near villages remains the major factor in providing people a high quality of life. Several such clusters of villages can still be seen in Western Ghat region of Uttar Kannada district of Karnataka. It is true that in recent decades the forests of this district have come under a tremendous strain due to a number of factors (including commercial exploitation for industrial-urban use and indiscriminate mining) but the destructive impact of deforestation seen elsewhere has also motivated people to get organized for the protection of remaining forests.

Thanks to Appiko– people’s movement for saving forests– which started in 1983, today we can visit several forests which would have vanished but for the timely action to save trees. It is a blessing to be able to stand in the middle of this greenery and to think that all this was protected by the people. Appiko and Chipko mean the same (hug the trees).

For me, just a walk in a village like Gubbigadde (people from where had been enthusiastic participants in the Appiko movement) gave a fair idea of the importance of forests in the life of people. I took only a 15 minutes walk and found that there are so many types of vegetable and medicinal plants just growing wild whose uses are very well recognized by the people and they describe in detail their virtues. I was initially full of questions but soon information on the use of various plants came in such torrents that I soon grew tired of taking notes. When I entered a house, I was informed how different types of wood had been used for the upper, middle and lower portions of the door. When I expressed admiration of a small basket, my village friends hastened to show me the many different types of baskets, all made from the material obtained from the nearby forests, which were available with a single household.

Then there were the numerous types of implements, for domestic use as well as for agricultural fields- ranging from the humble broom to the sturdy plough. Above all the forest provides the even more basic daily needs of fuel, fodder and water, I learnt. The forest’s gift of leaf manure has a special significance. This district is famous for its mixed gardens of arecanut, banana, black pepper, coconuts and cardamom which have been able to flourish largely because of the green manure and overall conducive environment provided by natural forests.

Due to these manifold contributions of forests it is not difficult to understand the pain which the people of Gubbigadde (literally meaning the village of sparrow field) and other villages felt when the forests near their villages were auctioned to meet the needs of plywood industry or for other industrial- urban requirements. These villages also have a tradition of opposing anti-people forestry practices going back to the days of the British rule. The people were anxious for some action to protect trees and they listened with rapt attention when Pandurang told them inspiring real life stories of how the people of several Himalayan villages, especially women, hugged trees to prevent them from being axed.

Around the same time Sunderlal Bahuguna, the venerable leader of Chipko movement from Himalayan region, also visited Karnataka. As the people here were full of questions about deforestation and how to check this, a local youth club invited him for a public meeting in Gubbigadde village. The presence of this veteran of several difficult struggles and the inspiring stories he told about the non-violent struggles to save forests inspired the people further to initiate action for protection of forests near their own villages. People of Salkani village had already written protest letters to forest officials. Now the people were waiting for some direct action.

The opportunity came soon enough in September 1983 when the Forest Department started felling trees in the Kalase Forest. Even though this forest was located far away from the village settlements, as soon as the news reached Salkani and Gubbigadde villages, efforts were started to mobilize people for reaching the tree-felling site.

On the morning of 8th September 1983 about 160 people started their march towards Kalase, Kudgrod forest. Braving rain and ignoring leaches that clung to their feet, crossing a river on a hanging rope bridge, the people rushed towards Kalase with the determination to prevent any further axing of trees. When they reached the forest, some of them rushed towards a tree which was being felled and embraced it. The axmen were stupefied. How could they axe a tree which was being embraced by human beings?

Surprisingly the forest workers were not all that opposed to the basic concerns of the people and agreed to stop the work till senior officials came. On 22nd September 1983 the District Forest Officer came with scientists and influential people. At first he said that the tree felling was scientific and will continue, but this reasoning broke down at the felling site when a scientist accompanying the official himself said that the allegations of excessive damage were correct. He said that the people should be complimented for having brought this to the notice of the authorities.

Husri village was the next major site of confrontation. In 1969 a natural forest of 900 acres had been clear felled here to raise a eucalyptus plantation. This had played havoc with the forest-dependent life of villagers, but fortunately one part of forest was still left for them. In 1983 the Forest Department sent axe men to fell nine trees here. The people decided to resist this. About 200 of them marched to the forest and embraced the trees. A tense situation was prevented from worsening when the official present was persuaded to take the view point of villagers to senior officials and the Minister of Forests.

It will be interesting to know what happened at these Appiko confrontations in remote forests in greater detail. Pandurang Hegde has given a detailed description of the Husri movement confrontation, “About 200-250 people have gathered in forest. People in groups are near trees to prevent felling. Axemen (labourers) are standing helplessly. The forest officer’s jeep is seen about 2 furlongs away. But no body goes there. The jeep stops near the road. The DFO with Range Officer and contractor walks towards the people. As he reaches near the gathered people, people give respect to the officer.

Returning their greetings he asks what are young people doing?

One man: Hugging trees to save them from axmen.

DFO: We also take care of trees. But there is a need for fuel wood. The trees cut here will be used as fuel wood in Sirsi town. If you stop felling then there will be fuel wood shortage in Sirsi and grave problems.

Villager: You can take dead and dry trees but not green ones. Another person: Once you cut down this forest there will be no trees left. What will you do once the total forest is gone? From where will you bring fuel wood?

Villager (An old man):

Yes? You plant teak and eucalyptus-moving his hand towards eucalyptus plantations. And is that you are going to plant? And will this be used for fire wood.

DFO (little puzzled):

That was done previously. But here we will plant trees which will yield firewood.

Villager (a middle aged man):

This is good. But where will we get green leaves for manure and wood for agricultural implements?

Another man: We cannot use eucalyptus and teak for green manure nor for manufacturing agricultural implements.

DFO (does not answer these questions).

You see there is urgent need for fuel wood. Allow us to cut trees otherwise problems will be created in town. Dead and dry trees as you suggested is good idea. But it takes time. So allow us at least a year’s time.

Villager:

If we allow you a year our only forest near the village will be cut down. Then? Where are we to go? Can you get us back these forests? The trees, which are useful for us? Forests are not just for villagers. There are people in other areas too. They also need fuel wood, timber. As you get grains from outside, we also need fuel wood, timber. As you get grains from outside, we also have to give forest products. Young man speaks: Sir, when we have enough then whatever is left we will give to others. If we are hungry can we give out food to others?

DFO (no answer, diverts the topic):

Look if you want to solve these problems why don’t you go and meet the minister?

The elderly person: Sir, as you came here in the midst of forest and saw the situation, we can make you understand our problem, what use is it to go to a minister in Bangalore? He is too busy to understand. And moreover he will not know any of our problems without visiting this place. We have already sent memorandum. Like you have come, minister should also come here to understand the situation.

DFO: The order to fell trees has been signed by the governor. I cannot do anything. I cannot order to stop cutting of trees.

Villager: We agree you cannot change the order. But if trees are felled we will not allow a single tree to be harmed by an axe man. We will hug the trees.

Another person: We want forests, which give us rain, manure, fuel wood for agricultural implements. We will not allow it to be used for fuel wood and timber. Forest is ours, we need it, it is for our survival. They produce soil, water and natural fertilizers.

As the forest officer tries to go away, a part of the crowd discusses about gheroring him for the whole day. However the organizers of the movement persuade them and make them understand that this is different from any political movement. Gherao is expressing anger. It does not lead us anywhere. Our goal is to change forest policy. So it is of no use harassing any individual.

The DFO goes away on jeep. The villagers hold a meeting and take a pledge to protect the forest at any cost, even at the cost of their lives.”

In the first phase the Appiko movement had spread within a short time to 8 areas – Mathghatta, Salkani, Balegadde, Husri, Nedgod, Kelgin Jaddi, Vanalli and Andagi.

In the last week of December 1983 the much awaited visit of the Forest Minister to Kalase and other affected areas came. People turned out in large numbers to present their view point to him, The Minister gave specific orders to stop the felling of several marked trees and said that in future only dead and dry trees will be cut from here.

In April 1984 some Appiko activists decided to go on a long foot march to take their message to a wider area. This march started from Sirsi town on 10th April 1984 and after covering about 650 kms. The marchers returned to Sirsi on 29th April 1984. Such foot marches enabled the movement’s message to spread to a wider area and also helped the activists to get a firmer grasp of the realities.

Within three years the movement had also spread to the districts of Shimoga and South Kanara districts. In some villages resources were mobilized initially be daily collection of handfuls of grains. The traditional theatre of Karnataka ‘Yakshagana’ was adopted to spread the movement’s message. The ‘appiko’ movement was not concerned only with confrontations. Following the ban on green felling after 1989 the movement gave more attention to regeneration of degraded land.

Pandurang Hegde and other Appiko activists started getting frantic calls from other areas to come to help in forest protection initiatives. This was different from earlier efforts as now they had to go to new areas. Here they did not have previous familiarity with the people with whom they were interacting. In some places local politicians tried to make use of the popularity of the new movement to serve their own narrow interests. All this sometimes created a difficult situation for Appiko activists from Uttar Kannada. They had to visit the site of tree-felling and then mobilize people to check this. In Coorg they learnt that the lawyer who contacted them was based in Bengalaru and came here only from time to time. So the work for them increased.

Undeterred by these difficulties Pandurang Hegde and Appiko activists plunged themselves into spreading the movement in many new areas. As they found the right contacts several reliable and committed local allies emerged who took on a lot of responsibilities. These included A.C.Subbaiah in Coorg and Shampa Daitota and Hari Rao Marlaje in South Canara.

Several early successes became possible because of the high levels of dedication and commitment shown by several emerging village leaders and activists such as Mahabaleshwar Hegde and Vijaya. They came forward not only to hug trees in very difficult conditions, but also contributed with their special skills in music and songs. Others participated in street plays and folk theatre (Yakshagana) presentations of the issue to take the message of the new movement far and wide. After her marriage Vijaya settled in Bengaluru and helped to spread the appiko message there. G.G.Hegde came forward to offer local support to Pandurang Hegde in such a way that he could devote all his time and energy to spread the new movement . In the success of the Belagadde movement, initial ground work had been done by two youths Ishanna and Mablu. There was excellent media coverage by the Kannada and English media and this helped people in several distant places of the region to initiate tree protection work in their own ways. They needed the help and support of Pandurang Hegde and other Appiko pioneers to take forward their new forest protection efforts.

The Appiko movement had one of the most successful beginnings among the various social and environmental movements in India as tree-felling could be checked at several places. This success peaked in 1990 when the State government imposed a total ban on the felling of green trees within natural forests. The order stated: “The ban on felling will continue in the evergreen forests of Western Ghats with the objective of maintaining the ecology and environment. Only dead trees will be permitted to be removed. Care should be taken to see that no damage is caused to other standing trees while removing dead trees from the forest.” The order confirmed that this ban does not apply to artificially raised plantation species such as eucalyptus, teak, acacia and Casuarina.

This was a truly amazing achievement for the Appiko movement as, when the movement started in 1983, the tree felling was being fully justified by the government as ‘scientific’ felling. Within just 7 years the Appiko movement had been able to mobilize even support of people and collect even evidence to convince the state government to take such a major step as announcing a ban on felling of green trees in the natural forests of a very wide area.

While those who participated in various Appiko struggles to protect forests certainly played the most important role in this achievement, an important role was also performed by several others- for example those who helped in the organization of foot marches or who helped in the dissemination of incipient movement’s message far and wide. The media also played a very important role, and while it may not be fair to single out any individual in the media, the name of the then consultant editor of the Deccan Herald Shri Ajit Bhattacharjee, one of the most eminent editors of India who always encouraged such causes can nevertheless be mentioned as someone who took a very keen interest in providing adequate space to the young movement’s activists. This also helped Pandurang Hegde find a space in Karnataka’s leading newspaper to highlight the aspirations and messages of nature protection and Appiko movement.

For Pandurang those were the busiest and rewarding years of his life as the young man mobilized all the energy of his youth to simultaneously work on many fronts. He tried to consolidate the struggles in the areas where the movement started, while at the same time traveling to several new places where he did not even have any previous contacts. At the same time he took up the academic and research work necessary for providing the rationale for the demands of the Appiko movement.

What is more, Pandurang realized at an early stage that struggles should be combined with constructive activities emphasizing many sided efforts to link protection of environment with protection of livelihoods. While indiscriminate tree felling sanctioned by the government had to be opposed, people also needed to be self-disciplined while obtaining various kinds of minor forest produces so that trees were not damaged.

Summarizing this philosophy of the movement, Pandurang wrote,

“Inspired by Chipko the Appiko movement evolved its own philosophy of conservation and regeneration of natural resources in the tropical western ghat region. The broad goal is to strive towards establishing a harmonious relationship between human beings and nature while protecting the tropical forests. The Appiko coined the slogan in Kannada as Ulisu, Belasu and Balasu. Ulisu in Kannada means, to save, Belasu is to regenerate the forests and Balasu means rational use of the tropical forests.

The coverage of existing natural forests in Western Ghats is very scarce. Good naturally grown forests remain only in the interior hill regions or inaccessible mountain ranges. But there are constant threats to these existing forests from numerous development schemes like dams and infrastructure projects like railways and power plants. These natural growth forests play a very important role in providing water and food security to millions of people in and around the Western Ghats. In order to protect the interests of the communities and forest dwellers. Appiko Movement aimed at protecting these remaining forests through grass roots action, creating awareness among the local communities and direct action. Many such grass root groups are keeping vigil to conserve the remaining tropical forests. Appiko has become synonymous with forest conservation as people take to direct action even in cities like Bangalore to protect trees from being felled.

In Belasu, growing the forest, emphasis is on natural regeneration of the indigenous species. And in planting following the philosophy of five F species. These are Fruit, Fodder, Fuel wood, (Natural) Fertilizer and Fiber. This activity of regeneration is to be done by the village communities involving forest dwellers and women. Additional emphasis is on growing the non-timber forest produce that helps in providing the livelihood to forest dwellers. Thus, forestation is an alternate to the existing logging activity, helping them with a source of income and employment.

The third objective of Balasu, is to evolve methods of using the forest and other natural resources rationally, without harming the resource base. To achieve this objective there is work with the communities to install fuel saving stoves, solar devices, and bio gas plants to propagate the alternative energy resources.

Appiko is actively involved in helping forest dwelling communities to carry out sustainable harvesting of non timber forest produce and value addition to increase their income. These opportunities provide the livelihood options for the forest dwelling communities in tropical forest region. These are economically viable and ecologically sound with least impact on the existing natural resources, especially the tropical forests.”

However the first area of priority for the Appiko Movement remained saving the natural tropical forests of Western Ghats. “The area is so sensitive that to remove the forest cover will lead to a laterization process, converting the land into Rocky Mountains. Thus a renewable resource becomes a non-renewable one. Once laterization sets in, it will take centuries for trees to grow on that land. Before we reach such an extreme point the Appiko Movement aims to save the remaining forests in the Western Ghats through organizing decentralized groups at the grassroots level to take direct action.”

The urgency of saving natural forests became all the more important as the government was concentrating more on creating industrial plantations. According to Pandurang,“Monoculture plantations are a problem as they do not produce useable fodder and lead to erosion of the soil. When farmers tried using acacia leafs for fertilizer they were struck with new diseases on their plantations, it was also found that worms from teak were affecting cattle. The availability of grazing for livestock suffered a decline as commercial species are planted at such high density they do not produce grass. Plantations also caused the invasion of the non-palatable weed, eupatorium which further inhibits grass growth. Fast growing also means a greater absorption of water. Hence whilst the natural forests help to keep the air cool, monoculture plantations lead to less rain and increased temperatures.”

Hence clearly there was a continuing need to check various distortions in the government’s policy, particularly as some international aid agencies also had a similar agenda of promoting mainly the industrially useful species of trees. In addition even after the legal tree-fellings were stopped by the government, some tree felling continued illegally and a lot of vigilance had to be exercised by rural communities to check this. Pandurang, too, got involved in several cases of helping rural communities in opposing and stopping illegal felling of trees.

However the opposition to the promotion of mainly industrially useful species of trees was more complex as international aid agencies had given a false pro-people orientation to this by attractive packaging of community forestry, although community’s participation was only marginal and the main emphasis remained on promotion of commercial species of trees and overall commercialization of forest policy. In the long run this would lead to increasing alienation of people from forests, although in the short run money provided by aid agencies could be used to hide this fact.

Keeping this in view, Pandurang was firm in his opposition to such aided projects which further increased the distortions of the existing official policies. As he later stated in an interview with the famous British writer Jeremy Seabrook (published in the New Internationalist in 2009)-

“In the early 1990s the British Overseas Development Agency (the ODA, later known as DFID) was invited by the Karnataka Government to implement a programme for reforestation of the Western Ghats. The ODA initially mixed acacia with teak and about 10 per cent of indigenous species. Pressure from the people forced them to set up an independent inquiry, which argued in favor of people’s forest management. The report said the ODA was continuing commercial forestry by another name. To our amazement, the ODA was convinced. The Government terminated the programme: the bureaucracy could see it meant the end of its illegal felling activities.

From this victory rose a more powerful threat. An arrangement was agreed with the Japanese government for a sum (of aid) 10 times the amount offered by the ODA. There was no participation and no planning. There was a reversion to monoculture. They planted mostly acacia for the pulp and paper industries. The Government has stated the outcome is a great success but it has not published any reports. The Japanese aid is in the form of a loan at three per cent interest. Many NGOs have been given money, which they have accepted.

Appiko, too, was offered funds but refused. Our role now is to remain as watchdogs over development. Many NGOs have been co-opted by money. They go to the villagers and seduce them with promises of earnings. In fact, if the villagers get five per cent, the NGO gets two per cent, the bureaucracy gets the rest.

We reject the industrialization of aid: turning aid into a kind of business, where returns are expected and cost-recovery is part of the conditions on which it is provided. It is increasingly mechanistic – target groups and beneficiaries; indicators that tell you nothing of how people’s lives are affected. You cannot blame the NGOs for going along with this. It is the contemporary context. NGOs provide charity to disaffected intellectuals of globalization- call them consultants and professionals and they are happy.”

This campaign proved to be successful in its first phase as following the objections of Pandurang and other activists of the Appiko movement, helped by friends like Nicholas Hildyard and Jeremy Seabrook in Britain, the DFID( Department for International Development) agreed to carry out a review of its Karnataka forestry project. This review committee was chaired by an eminent expert and senior official Dr. N.C.Saxena. In its final report, this review committee confirmed some of the most important objections raised by the Appiko movement. On the basis of this report, the DFID project was altered to meet people’s prioritiesa.

However this success of the Appiko movement proved to be short lived, as alternative funding for another similar project with the same distorted priorities became available from Japanese aid agencies. The Japanese aid authorities, moreover, were not at all responsive to any objections from people’s movements like Appiko. As the resources available with this project were much more than in the case of the previous ODA project, the authorities should have been more careful about the impact of the aid project. But they chose to simply ignore the objections of appiko and did not even respond to several of their communications.

As Pandurang recalled later, “Whatever the problems with their project, the ODA/DFID was at least willing to listen patiently and carefully to objections, and they agreed to ask for a review on the basis of these objections. But the Japanese aid authorities were very different – they simply ignored what was being said by us.”

So despite its many sided early successes, the Appiko movement also had to learn to live with some limitations of its efforts.

Bharat Dogra is Honorary Convener, Campaign to Save Earth Now. His recent books include Protecting Earth for Children, Planet in Peril, Earth without Borders and Man over Machine.