India is facing a ‘hunger and malnutrition emergency’. In this article, we discuss how the various schemes meant to address the nutrition requirements of the people have fared in Union Budget 2024-25.

India’s Grim Poverty Situation

The Economic Survey 2023–24 says that India’s “growth has been inclusive” and “human development indicators have improved”. It cites data from a Niti Aayog document released in early 2024 to claim that “24.82 crore people have escaped multidimensional poverty between 2013–14 and 2022–23.”[1]

In an earlier article of this budget series, we have discussed in considerable detail the problems with the new poverty index developed by Niti Aayog to artificially show that poverty in the country has considerably declined. We have also presented extensive data, both from official sources and other reputed studies / reports, to show that the poverty situation in the country is appalling — at least 60 to 70% of the country’s population does not earn what can be called a living wage and lives in destitution.[2]

Hunger and Malnutrition ‘Emergency’

Such terrible poverty levels have also resulted in a ‘hunger and malnutrition emergency’. In the same article mentioned above, we have given considerable data on this. Unfortunately, an insensitive and callous Modi government is denying these heart-wrenching facts, and has manufactured data to claim that the the nutritional status of the Indian population is improving![3]

Very recently, the Global Hunger Index (GHI) 2024 has been released. It says that the level of hunger in India is ‘serious’ and ranks India 105th among 127 countries for which the ranking was done (high income countries with neglible hunger levels are not ranked). GHI-2024 suggests that India’s undernourished population this year would effectively rank as the seventh most populous country in the world — with roughly the population of Brazil, a staggering 200 million people. The GHI is a report brought out annually by two European organisations that attempts to track and measure hunger globally as well as by country.[4]

Every year, on the release of the GHI report, the Modi Government has disputed its findings, claiming that the GHI is a flawed indicator and that it is a conspiracy to malign the country and derail the government’s ‘Viksit Bharat’ agenda. Probably no government in the world disputes the data and methodology of such reputed international organisations so much as India does. Commenting on the Modi Government’s denial of ‘bad news’, The Economist recently wrote: “Denial is the first, and often the only, response of India’s government to bad news.” It goes on to give some examples of how the Modi Government has responded to ‘bad news’: “Last year the Global Hunger Index, a measure of undernutrition, ranked India 111th out of 125 countries. The government said it had ‘serious methodological issues’. India ranks 176th of 180 countries on an environmental index. ‘Unscientific methods’. What about the World Bank’s human capital index, which measures health and education? ‘Major methodological weaknesses’. The World Press Freedom Index? ‘Methodology which is questionable’. The Freedom in the World Index, Democracy Index and indices? ‘Serious problems with the methodology’. Sometimes the government does not even like its own data. In 2019 it withheld the release of unflattering consumption numbers, promising fresh ones with ‘a refinement in the survey methodology’.”[5]

Budget 2024–25: Nutrition Schemes

Anyway, let us return to our 2024 Union Budget analysis and examine how the various schemes meant to address the nutrition requirements of the people have fared in this budget.

i) Food Subsidy

This is the most important programme in the country to tackle hunger and malnutrition. Under this, the government provides essential rations to the poor at subsidised rates through the public distribution system (PDS). This food subsidy programme is mandated under the National Food Security Act (NFSA), passed by the Parliament in 2013.

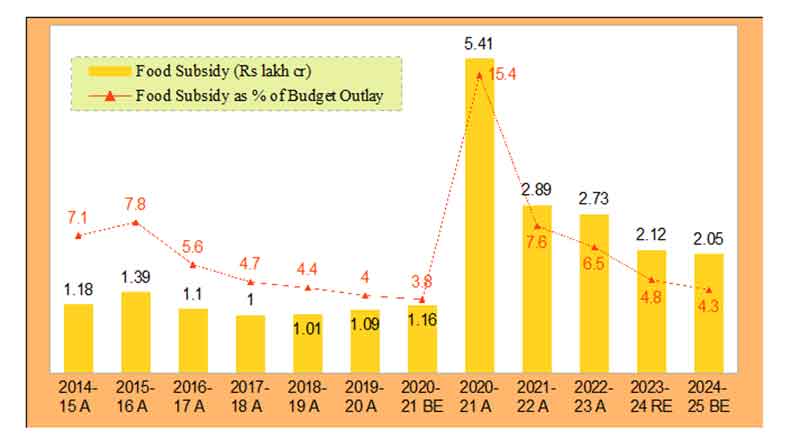

In a country with such mind-boggling levels of hunger and malnutrition, the NFSA provides very inadequate relief; nevertheless it is a bare minimum lifeline for the poor. But such is the coldheartedness of the Modi Government that it has been seeking to reduce its food subsidy spending ever since it came to power in 2014. During its first term, actually till before the pandemic struck in 2020 (that is, over the period 2014–15 A to 2020–21 BE), the food subsidy budget as a percentage of budget outlay continuously declined — the decline was so steep that allocation under this head in 2020–21 BE (Rs 1.16 lakh crore) was less than the allocation for 2014–15 (Rs 1.18 lakh crore) even in nominal terms. As a percentage of budget outlay, it had fallen by half (from 7.1% to 3.8%) (see Chart 1)! Instead of strengthening the PDS, the Modi Government was more interested in exporting foodgrains to earn foreign exchange, so much so that our country had become the world’s biggest rice exporter[6] — in a country that accounts for one-third of the severely food-insecure population in the world.[7]

Chart 1: Modi Years: Food Subsidy Budget, 2014 to 2024 (Rs lakh crore)

Then, during the first year of the pandemic (2020), due to the widespread distress caused by its callous handling of the pandemic, the government was forced to increase its food subsidy budget and provide free rations to the people. The budget papers reveal that the government’s food subsidy budget (2020–21 A) increased by more than 4 times to Rs 5.41 lakh crore, as compared to the budget estimate of Rs 1.16 lakh crore (Chart 1).

Since then, the government has been claiming that the economy has rebounded and we have emerged as the fastest growing economy among the G20 economies. It is also claiming a dramatic decline in poverty levels in the country. So, it has once again started reducing its food subsidy budget, even in nominal terms. The food subsidy this year is 62% less than the peak reached in 2020–21 A (Rs 2.05 crore). And as a percentage of budget outlay, the fall is even more — it is 73% less than in 2020–21 A (4.3% as compared to 15.4%); it is even less than the allocation made in 2014–15 (7.1%), by 40% (Chart 1).

The NFSA law says that up to 75% of the rural population and 50% of the urban population are to be provided rations under the Act based on the latest census. The 81 crore people in India who are presently being given rations under NFSA are as per the 2011 Census. Since then, population has increased. Had the 2021 census been conducted and NFSA coverage revised accordingly, an estimated 10 crore people would have been added to the food security net. In response to a PIL filed in the Supreme Court, the Court in 2022 ordered the Union government to re-determine the NFSA coverage in States and Union Territories using population projection figures and expand coverage. The Centre strongly objected, saying that coverage could only be expanded after the Census. In 2023, the Court ordered that ration cards be issued to the eight crore migrants/unorganised sector workers who do not possess ration cards under NFSA and are registered on the E-shram portal (National Database of Unorganised Sector workers). This number was provided to the court by the Union government. Since then, more than a year has passed; the Centre has used all kinds of tricks to delay the implementation of the Court’s orders. Again this year (in July 2024), a week before the presentation of the Union Budget, the court hauled up the Union and State governments for continued non-compliance with its orders, and gave them four weeks to comply. It was therefore expected that the food subsidy budget would see an increase so that additional allocation of food grains could be made as directed by the Supreme Court. Instead, the Centre has reduced the food subsidy budget this year — to Rs 2.05 lakh crore, from last year’s revised estimate of Rs 2.12 lakh crore.[8]

Why is the Centre so unwilling to expand NFSA coverage and provide essential rations to the poorest of the poor? That is because the Modi Government has been seeking to undermine the NFSA ever since it came to power in 2014–15. In its very first year in office, it set up the ‘High Level Committee (HLC) on Reorienting the Role and Restructuring of the Food Corporation of India’, headed by the BJP leader Shanta Kumar. The committee recommended that the government:

- reduce public sector grain stocks;

- replace public procurement of grains with cash transfers to farmers;

- defer implementation of the NFSA;

- drastically reduce the percentage of the population to be covered under the NFSA; and

- steeply hike the issue prices of foodgrain.[9]

This is the real reason behind the push made by PM Modi and FM Jaitley to implement the JAM trinity — Jan Dhan (bank accounts), Aadhaar and mobile telephony. They have now become near universal. In the medium term the government’s plan is to implement the Shanta Kumar Committee recommendations, gradually eliminate the PDS, identify the poor through Aadhaar, and provide direct cash transfers to the poor into their Jan Dhan accounts (these direct transfers can then be gradually wound down to further reduce the food subsidy bill, just like has happened for cooking gas). Defending the plan, the government’s then Chief Economic Advisor Arvind Subramanian stated that this will enable the government to reduce its subsidy bill, enable it to invest the savings into infrastructure (that is, transfer it to the private sector through the PPP route), and simultaneously, “liberate” prices.[10] It is in accordance with this plan that the Modi Government rammed the three farm bills through the Parliament at the peak of the Covid crisis, but the farmers fought resolutely and forced the government to withdraw the bills.

Promotion of Bio-Fuels

The Modi Government claims that it has ‘successfully’ lifted nearly 25 crore people out of poverty and therefore, “the incidence of poverty has reduced remarkably”.[11] Agricultural sector growth rate has also been satisfactory, and the country has a comfortable stock of foodgrains.[12] And so while reducing the distribution of foodgrains through the PDS, it is diverting foodgrains to production of bio-fuels! It is promoting the production of ethanol from rice, corn and sugar, and has set a target of increasing the percentage blending of ethanol with petrol to 20% by 2025. To help meet the target, the government is offering financial assistance to biofuel producers and faster environmental clearances. It is even supplying rice to ethanol producers at prices cheaper than what States pay for their public distribution networks![13]

In a country with the largest number of hungry people in the world, the government is not willing to expand its public distribution system and provide foodgrains to the poor at subsidised prices, but is willing to provide foodgrains to companies at subsidised rates for producing biofuels to power swanky cars carrying the rich on expressways, also built at subsidised rates.

ii) Nutrition Schemes Aimed at Pregnant Women and Children

The previous governments had put in place several relatively smaller nutrition schemes oriented towards pregnant women and children. While the funding for them was inadequate, at least they attempted to address the problem. We discuss the budget allocations for the 3 most important nutrition schemes below.

a) Anganwadi Services / Poshan 2.0

This is the most important program of the Government of India to provide health, education and supplementary nutrition to pregnant and lactating mothers and children below 6 years of age. This scheme is implemented by the Ministry of Women and Child Development. It is implemented through a countrywide network of Anganwadi workers (AWW) and Helpers (AWH) working from Anganwadi centres (AWC).

A Niti Aayog report of 2015 had pointed out that our Anganwadi centres were in a bad shape:

- 41% of the Anganwadis have inadequate space;

- 71% are not visited by doctors;

- 31% have no nutritional supplementation for malnourished children; and

- 52% have bad hygienic conditions.[14]

In his first budget speech of 2014, Finance Minister Arun Jaitley stated that “a national programme in Mission Mode is urgently required to halt the deteriorating malnutrition situation in India, as present interventions are not adequate.” He promised to put in place a “comprehensive strategy” within six months. The centrepiece of any such strategy obviously needed to be improving the conditions of Anganwadi centres and increasing the budget allocation for Anganwadi services. But it was only another Modi JUMLA. After 2014, the word ‘malnutrition’ disappeared from all subsequent budget speeches. Rather than improving the quality of our nutrition and care program for mothers and infants, the Modi Government cut the budgetary allocation for this scheme.

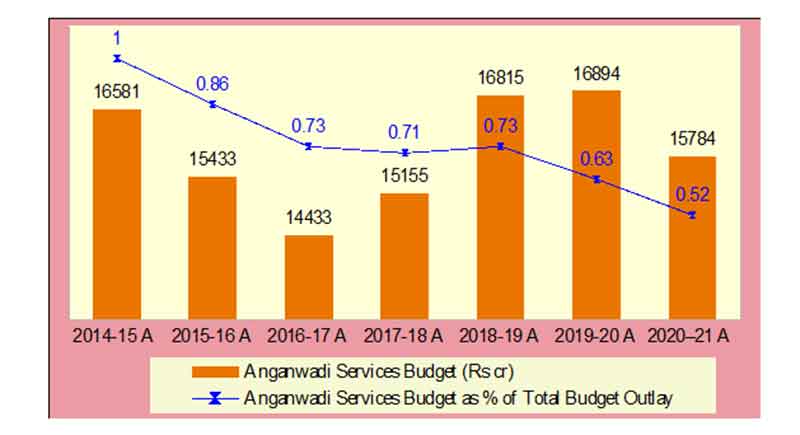

During the first seven Modi Budgets (2014–15 to 2020–21), the allocation for Anganwadi services fell even in nominal terms, from Rs 16,581 crore to Rs 15,784 crore. A better idea of the severity of the reduction can be had by calculating the budget allocation as a percentage of budget outlay — it has fallen by nearly 50% (from 1% to 0.52% — see Chart 2).

Chart 2: Modi Government Allocation for Anganwadi Services:

2014–15 to 2020–21 (Rs crore)

In 2021–22, the Modi Government resorted to its typical smoke-and-mirrors routine to fudge the allocation for this scheme by clubbing it with two other schemes — National Nutrition Mission and Scheme for Adolescent Girls. The new merged scheme was given the pompous name ‘Saksham Anganwadi & POSHAN 2.0’, known in short as Poshan 2.0.

The restructured mission consists of the following sub-schemes:

- Supplementary Nutrition Programme (SNP) for children (0–6 years), pregnant women and lactating mothers, and adolescent girls (14–18 years);

- Early Childhood Care and Education (ECCE) for children of 3–6 years;

- Anganwadi Infrastructure including modern, upgraded Saksham Anganwadi; and

- Poshan Abhiyaan.[15]

The Poshan 2.0 Mission has a five-year road map, wherein apart from several short term goals, it has an important target of upgrading all the 2 lakh AWCs as ‘Saksham Anganwadis’ and construct pucca AWCs in lieu of semi-pucca and rented AWCs in five years. According to a reply given in Parliament on 2 August 2024, the Minister of Women and Child Development stated that under the Mission Poshan 2.0 scheme, “40,000 AWCs per year are to be upgraded as Saksham Anganwadis for improved nutrition delivery and for early childhood care and education (ECCE). Saksham Anganwadis are to be provided with infrastructure better than the conventional Anganwadi Centres including internet/Wi-Fi connectivity through Bharat Net (wherever possible), LED screens, water purifier/installation of RO Machine, Poshan Vatika, ECCE books and learning material etc.” The minister stated in her reply that so far, the government has selected 92,108 AWCs for upgradation to Saksham AWCs across the country.[16]

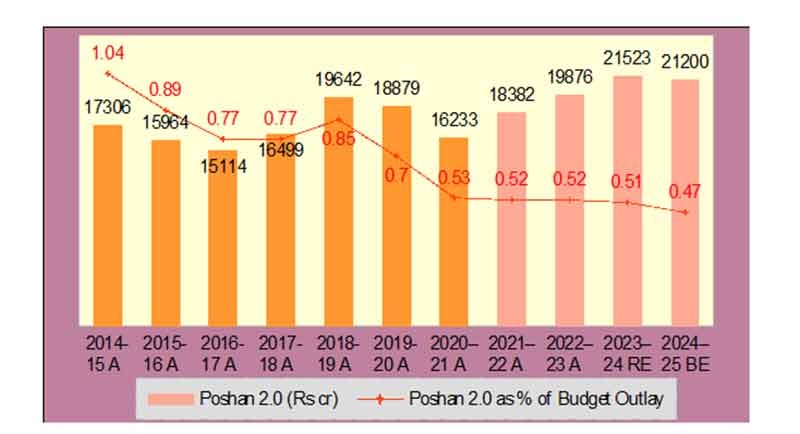

Improving the infrastructure of AWCs and developing them into Saksham AWCs requires an increase in budgetary outlay. But ever since the Poshan 2.0 Scheme was announced, the budget allocation has actually declined in real terms:

- The allocation for Poshan 2.0 has increased only marginally from Rs 18,382 crore to Rs 21,200 crore over the period 2021–22 A to 2024–25 BE. This works out to an increase of 4.9% per year (CAGR), which means it has declined in real terms.[17]

- If we compare the budget spending on the 3 constituent schemes of Poshan 2.0 in 2014–15 to the budget for Poshan 2.0 in 2024–25 BE, the increase is a paltry 2.1%. A back-of-the-envelope calculation reveals that in real terms, the allocation has fallen by a huge 44%.[18]

- The budget allocation for this scheme as a percentage of the total budget outlay has fallen by more than half in the eleven Modi budgets presented so far (see Chart 3).

Chart 3: Modi Government Allocation for Poshan 2.0

2014–15 to 2024–25 (Rs crore)

For the years 2014–15 to 2020–21, we have totalled the budget spending on all the 3 schemes that have been merged into Poshan 2.0: Anganwadi Services, National Nutrition Mission, and Scheme for Adolescent Girls.

The Poshan 2.0 Mission is to be implemented by Anganwadi workers (AWW) and helpers (AWH). The Modi Government keeps increasing their responsibilities, but only pays them a pittance — AWWs and AWHs receive a monthly wage from the Centre (the government calls it ‘honorarium’ so that it does not have to given them minimum wage) of Rs 4,500 and Rs 3,000 respectively, plus an incentive of Rs 500 / 250 per month (many States give them an additional honorarium). With such a low allocation for Poshan 2.0, this only means that their below poverty line wages are going to continue.

It reminds one of the fate of Modi’s promise to convert all Health Sub-Centres into Health and Wellness Centres. There are innumerable reports in the media about the condition of our Anganwadis — they continue to suffer from dilapidated buildings, lack of toilets, a significant number do not even have drinking water facilities.[19]

Supplementary Nutrition Program

Before 2021–22, there were two important Centrally sponsored schemes to combat malnutrition: (i) Supplementary Nutrition Programme (SNP) that provides hot cooked meals and take-home rations to children (under the age of 6) and pregnant and lactating mothers through the Anganwadis; (ii) National Nutrition Mission to “reduce the level of stunting, under-nutrition, anemia and low birth weight babies.”[20] Poshan 2.0 has merged both these schemes. The SNP is the largest component of Poshan 2.0.

However, the per head allocation for providing nutrition to children and women under this scheme is absurdly low. The cost norm for SNP was last revised in September 2017 by the Cabinet Committee on Economic Affairs (CCEA), to Rs 8 per day for children, Rs 9.5 for pregnant women, lactating mothers, and adolescent girls, and Rs 12 for severely malnourished children. There has been no subsequent revision in these norms. These are atrociously low norms — what can you give in Rs 10 today![21]

For SNP, funds are equally shared between the Centre and State governments. Even with the above low unit allocation for providing nutrition, it is estimated that in 2021–22, SNP required a total allocation (for both Centre and States) of Rs 42,033 crore to provide full coverage (that is, 100% of the target population). However, total approved budget (including both Union and State shares) was less than half (41%) of this, Rs 17,392 crore.[22]

Because of this low allocation for SNP, the quality of the services provided is very poor, and hence the total number of eligible people availing SNP services has fallen significantly. Between March 2016 and March 2021:

- the number of pregnant mothers and lactating women availing SNP services declined from 1.93 crore to 1.57 crore; and

- the number of children between the age 6 months to 6 years who availed of SNP services declined from 8.29 crore to 6.75 crore.[23]

This reduction in the most important nutrition scheme for our pregnant women and children, has taken place amidst a nutrition emergency. We repeat data from NFHS-5 of 2019–21 for emphasis:

- 36% of children in India under the age of five are stunted (indicating chronic or long-term malnutrition);

- 57% of women suffer from anaemia.[24]

The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World report by 5 UN organisations says that:

- between the trienniums 2014–16 and 2021–23, the proportion of people in India who experienced hunger and went for days without food (the report calls them severely food insecure) increased from 20.5 crore (15.6% of the population) to 31.2 crore (22.2% of the population), an increase of 50%.[25]

This only means that our ruling regime is totally insensitive towards the 5 crore children in the country who are malnourished, and the more than two crore pregnant women and lactating mothers, majority of whom are suffering from anaemia.

b) Pradhan Mantri Matru Vandana Yojana

This scheme was earlier known as the Indira Gandhi Matritva Sahyog Yojana (IGMSY). It was begun by the UPA-2 government in October 2010 on a pilot basis in 53 districts. The National Food Security Act (NFSA) passed by the Parliament just before the Lok Sabha elections in 2014 made it incumbent upon the incoming government to extend this scheme to all over the country. Under this, scheme, an allowance of Rs 6,000 is to be given to all pregnant women and lactating mothers (PWLM), to partially compensate them for wage-loss so that women can take adequate rest before and after delivery. This is especially important for women in the unorganised sector, who make up 90% of the country’s female workforce. Fear of losing wages often forces women in the informal sector to work through pregnancy and immediately thereafter, to the detriment of their own health and the health of their babies, who require at least 6 months of regular breastfeeding. This scheme also comes under the Ministry for Women and Child Development.

Despite this scheme being mandated by a Parliamentary law, the BJP refused to extend this scheme to all over the country for 3 years. Activists and academics mounted pressure on the government to implement the maternity entitlements, as they were much needed to tackle the huge maternal health crisis gripping the country: according to the WHO, in 2016, India accounted for 17% of all childbirth deaths in the world, with nearly 5 women dying every hour in India due to pregnancy and delivery related complications.[26]

Prime Minister Modi finally announced the implementation of these entitlements in his address to the nation on 31 December 2016. But as is his wont, he repackaged the programme and proudly presented it as a new scheme, the Pradhan Mantri Matru Vandana Yojana (PMMVY). The new scheme reduced the financial support given to PWLM during the first pregnancy to Rs 5,000, from Rs 6,000 stipulated in the NFSA.[27] It also limited the benefit to first live birth, again contradicting the NFSA which granted this financial support to all pregnant and lactating women. (In 2022, the scheme was revised and now offered an allowance of Rs 6,000 to a second child, if the infant is a girl. The aim is to discourage female foeticide.)

Following the PM’s announcement, the then FM Arun Jaitley announced an enhanced allocation for PMMVY in his 2017 budget.

It is a very insensitive government in power. It found a way to reduce the allocation for pregnant women, one of the most high-risk groups in society who need utmost care. The FM introduced conditionalities such as institutional delivery and full vaccination for women to be eligible for this financial assistance. These conditionalities actually end up excluding 60% of the country’s women, because they don’t deliver in hospitals, and/or are unable to vaccinate their children. But they are the ones who need these maternity benefits the most, as they include women from the poorest sections of the population, belong to Dalit and Adivasi communities, and live in the remotest areas of the country. They are unable to deliver in hospitals or vaccinate their children, because of the terrible state of government health services in the country.[28] Instead of focussing on improving facilities in government hospitals, and making hospitals more accessible for the poor (by improving ambulance facilities), the suit-boot sarkar’s FM/PM put the blame on the victims of our dismal public health system, and excluded them from receiving maternity benefits!

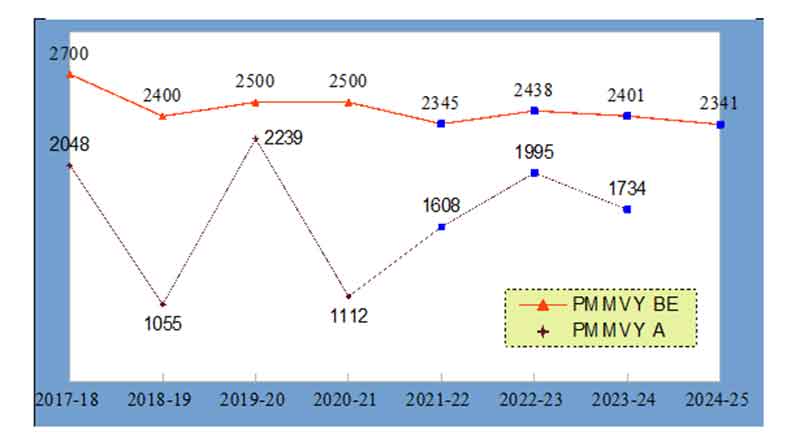

Because these conditionalities excluded a majority of women from this scheme, the FM saw no reason to allocated enough funds to cover all the eligible PWLM in the country. For the first year (2017–18), he allocated only Rs 2,700 crore (and spent only Rs 2,084 crore), whereas a budget outlay of Rs 3,870 crore was needed to provide the assistance of Rs 5,000 promised under PMMVY to all the estimated 129 lakh mothers who were eligible for receiving assistance under the scheme.[29] In 2018–19, the number of eligible women increased to 130.9 lakh and in 2019–20 to 132.7 lakh.[30] But as we can see from Chart 2, the FM reduced the budget allocation, and actual spending was even lesser. Consequently, according to an estimate by Accountability Initiative, only 35% of the eligible PWLM had been covered under the scheme as of 2 January 2020. The money is paid out in 3 instalments to each beneficiary; only 44% of the women had received all three instalments.[31]

To fudge the insufficient allocation being made under the scheme, in 2021–22, the FM merged PMMVY with six other women empowerment schemes under a new head ‘Samarthya’. In the subsequent years, the FM again reshuffled the umbrella schemes, to include some more schemes under Samarthya. But all these schemes have very tiny budgets; we estimate that around 93% of the total budget for Samarthya is spent on PMMVY. Based on this assumption, we have plotted the budget for PMMVY in Chart 4 (for those years for which this figure is not available). As we can see from the chart, in no year has the budget allocation crossed the 2017–18 BE allocation of Rs 2,700 crore. And except for the year 2019–20 A, actual spending has remained way below the budget estimate!

Chart 4: Allocation for PMMVY, 2017–18 to 2024–25 (Rs crore)

For 2023–24, the figure for PMMVY is revised estimates (actuals is not available).

We have assumed that the budget estimate and actual spending for PMMVY constitutes 93% of the total budget for ‘Samarthya’ for the years where separate budget for PMMVY is not available. These years are marked in square icons in blue.

This only means that an overwhelming number of PWLM continue to be denied their maternity entitlements under one excuse or the other. According to a press release of the Ministry of Women and Child Development (MWCD), as of 15 July 2022, a total of 257.6 lakh women had been given maternity benefits during the five-year period 2017–18 to 2021–22 and upto 15 July 2022 in the financial year 2022–23, or roughly 50 lakh women per year.[32] This figure is way below the total estimated number of pregnant women and lactating mothers in the country. A budget brief by Accountability Initiative estimated that total number of eligible PWLM in 2022 was 198 lakh — implying that only a quarter of them were receiving the promised financial assistance![33]

The payment to the beneficiaries is made in 3 instalments (since 2022-23, this has been reduced to 2). An RTI response by MWCD admits that in 2019-20 and 2020-21, in a majority of the States, less than 50% of the eligible citizens had received all the 3 instalments.[34]

The above mentioned budget brief by Accountability Initiative estimates that in FY 2022–23, the total budget allocation required to cover only the first live birth was Rs 8,204 crore. The budget allocation was less than a third, and money actually spent was less than a quarter, of this amount (see Chart 4).

A financial assistance of Rs 5,000 to pregnant women and lactating mothers is actually a very inadequate sum. The total budget outlay for this works out to only Rs 8,200 crore, which is a tiny sum for a country like India — which has the world’s third largest number of billionaires. Yet our PM and FM do not see it fit to allocate this small amount for our pregnant women and lactating mothers. What a shame!

c) Mid-day Meal Scheme

This is another important nutrition programme to combat the huge malnutrition levels among children in the country; an additional objective is to improve school enrolment and child attendance in schools. The scheme covers all government, local body, government-aided primary and upper primary schools, and the Education Guarantee Scheme/Alternate Inclusive Education centres (including Madarsas and Maqtabs) across the country. Allocation for this comes under the Ministry of Education. A footnote to the budget document of the Department of School Education and Literacy says that this scheme “is one of the foremost rights based Centrally Sponsored Schemes under the National Food Security Act, 2013 (NFSA).” This scheme has also been renamed after our PM. Earlier called the National Programme of Mid-Day Meals in Schools, it has now been rechristened ‘Pradhan Mantri Poshan Shakti Nirman’ or PM-Poshan.

But it is only hollow theatrics. The Modi Government is not willing to allocate a decent amount for providing one nutritious meal a day to our children, despite the fact that more than one-third of our children under five — about 4.7 crore souls — suffer from stunting. The budget papers show that the amount spent under this scheme last year (2023–24 RE) was less than the actual amount spent during Modi’s first year in power (2014–15). On paper, the allocation this year has been hiked by 25% over last year’s RE, but it is actually less than the amount spent in 2022–23. Even assuming that the full allocation this year is spent, it amounts to an average annual increase of only 1.71% over the actual spending in 2014–15, implying a reduction in real terms of 32% (Table 1).[35]

Table 1: Allocation for Mid-Day Meal Scheme, 2014–15 to 2024–25 (Rs crore)

| 2014–15 A (1) | 2022–23 A | 2023–24 RE | 2024–25 BE (2) | Increase, 2 over 1, % (CAGR) | |

| PM-Poshan (Mid-day Meal Scheme) | 10,523 | 12,681 | 10,000 | 12,467 | 1.71% |

iii) Total: Nutrition Schemes

Adding up the allocation for all the 3 important nutrition schemes discussed above — Saksham Anganwadi and Poshan 2.0, Samarthya and PM-Poshan (Mid-day Meals Scheme) — the total allocation is (21,200 + 2,341 + 12,467 =) Rs 36,008 crore. This is just 0.75% of the total Union Budget outlay!

Such is the commitment of the Modi Government to improving the nutritional status of our people, especially our women and children.

Notes

1. Economic Survey 2023–24, pp. 1, xii, 220.

2. Neeraj Jain, “Analysing Budget 2024–25 from People’s Perspective: Part 3: The Budget and Poverty”, 9 September 2024, https://countercurrents.org.

3. Ibid.

4. “Abject Failure: On India’s Global Hunger Index Ranking”, 17 October 2024, https://www.thehindu.com.

5. “India Cannot Fix its Problems if it Pretends They Do Not Exist”, 8 August 2024, https://www.economist.com.

6. Chris Lyddon, ‘Focus on India’, World Grain, January 12, 2017, http://www.world-grain.com.

7. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2024, https://www.fao.org.

8. “Expand Food Security Coverage to Benefit More Needy Persons, SC Tells Centre”, 24 August 2022, https://www.thehindu.com; Anjali Bhardwaj and Amrita Johri, “Food Subsidy: Union Budget Betrays Those Living with Hunger and Malnutrition”, 25 July 2024, https://thewire.in.

9. “Modi’s Farm Produce Act was Authored 30 Years Ago, in Washington D.C.”, RUPE, Mumbai, 17 January 2021, https://janataweekly.org.

10. For the full quote of Arvind Subramanian and more on this issue, see: “Constructing Theoretical Justifications to Suppress People’s Social Claims”, Aspects of India’s Economy, No. 62, January 2016, http://www.rupe-india.org.

11. Economic Survey, 2023-24, p. 33.

12. Ibid., p. 319.

13. India’s Ethanol Push: A Path to Energy Security, Press Release, Ministry of Petroleum and Natural Gas, 24 October 2024, https://pib.gov.in; “Modi Govt’s Ambitious Ethanol Plan Spurs Food Security Fears”, Bibhudatta Pradhan and Pratik Parija, 6 October 2021, https://theprint.in.

14. Sourindra Mohan Ghosh, Imrana Qadeer, “An Inadequate and Misdirected Health Budget”, 8 February 2017, https://thewire.in.

15. ‘Saksham Anganwadi and Poshan 2.0′ – an Integrated Nutrition Support Programme, Press Release, PIB, 2 August 2022, https://www.pib.gov.in.

16. Government of India Ministry of Women & Child Development, Lok Sabha Unstarred Question No: 2031, To be Answered on 02.08.2024: Saksham Anganwadi And Poshan 2.0, https://sansad.in

17. Our calculation, assuming average annual inflation of 6%.

18. CAGR. Our calculation, assuming average annual inflation of 6%.

19. “Toilets Don’t Work At 5600 Anganwadi Centres in Punjab, Haryana, Himachal Pradesh”, 31 March 2022, https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com; “Odisha’s 71% Anganwadis Don’t Have Access to Safe Drinking Water, 81% Lack Toilet Facility”, 10 April 2023, https://www.counterview.net; “Sub-par Food, Poor Infra — Anganwadis in Bad Shape”, 17 June 2024, https://www.newindianexpress.com.

20. From the footnote to the 2018–19 budget papers of the Ministry of Women and Child Development.

21. Avani Kapur et al., Budget Briefs: Mission Saksham Anganwadi and Poshan 2.0, GoI, 2023–24, https://accountabilityindia.in.

22. Avani Kapur, Ritwik Shukla, “India UnderSpends On Nutrition, New Nutrition Programme Yet To Be Implemented”, 31 January 2022, https://www.indiaspend.com.

23. Ibid.

24. Neeraj Jain, “Analysing Budget 2024–25 from People’s Perspective: Part 3: The Budget and Poverty”, op. cit.

25. Ibid.

26. “5 Women in India Die Every Hour During Childbirth: WHO”, 16 July 2016, https://indianexpress.com.

27. The government announced that the remaining cash incentive of up to Rs 1,000 would be given under a separate scheme called the Janani Suraksha Yojana so that on an “average” women get a total sum of Rs 6,000, as stipulated under the NFSA.

28. Maya Palit, “So Glad You Mentioned Pregnant Women, PM-ji. How About We Tell You What We Know About These Schemes?” January 4, 2017, http://theladiesfinger.com.

29. The number of beneficiaries (129 lakh) is an estimate made by Accountability Initiative (see: Budget Briefs: PMMVY–JSY–2020–21, https://accountabilityindia.in.) The calculation of Rs 3,870 crore has been done by us assuming a Centre–State cost sharing of 60:40.

30. Budget Briefs: PMMVY-JSY-2020–21, https://accountabilityindia.in.

31. Ibid.

32. Enrolments under PMMVY, Ministry of Women and Child Development, 29 July 2022, https://pib.gov.in.

33. Avani Kapur et al., Budget-Briefs: PMMVY–JSY–2023–24, https://accountabilityindia.in.

34. Ibid.

35. CAGR, calculated assuming an average annual inflation rate of 6%.

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

Neeraj Jain is a social–political activist with an activist group called Lokayat in Pune, and is also the Associate Editor of Janata Weekly, a weekly print magazine and blog published from Mumbai. He is the author of several books, including ‘Globalisation or Recolonisation?’ and ‘Education Under Globalisation: Burial of the Constitutional Dream’.