Twenty four years ago, on 22 October 1993, Bijbehara, my hometown, was struck by a vicious massacre that killed scores of peaceful protestors who were demanding revocation of a military siege of famous shrine, Dargah Hazratbal. According to the state government’s own magisterial enquiry report, “a procession of 2,000 to 3,000 people” that was “entirely peaceful and unarmed” was attacked by the paramilitary Border Security Force (BSF). The report establishes “beyond any shadow of doubt that firing upon the procession was absolutely unprovoked” and found that the paramilitary force “committed offence out of vengeance and their barbarous act … [was] deliberate and well-planned”.

Twenty four years ago, on 22 October 1993, Bijbehara, my hometown, was struck by a vicious massacre that killed scores of peaceful protestors who were demanding revocation of a military siege of famous shrine, Dargah Hazratbal. According to the state government’s own magisterial enquiry report, “a procession of 2,000 to 3,000 people” that was “entirely peaceful and unarmed” was attacked by the paramilitary Border Security Force (BSF). The report establishes “beyond any shadow of doubt that firing upon the procession was absolutely unprovoked” and found that the paramilitary force “committed offence out of vengeance and their barbarous act … [was] deliberate and well-planned”.

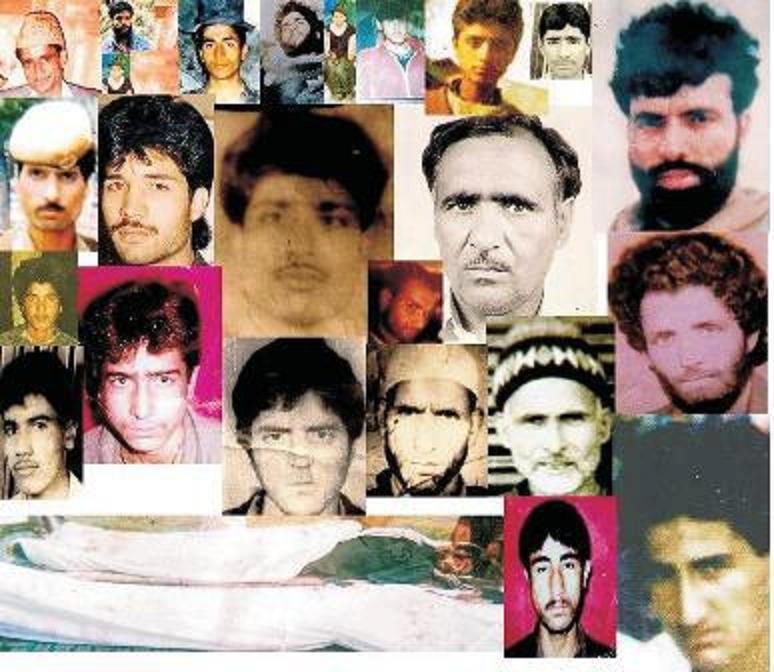

The brutality of the official insensitivity can be gauged from the fact that despite two and a half decades since the massacre, the actual number of the slain is unknown and remains disputed. The official enquiry claimed the BSF killed 31 civilians and injured 73 persons, but unofficial accounts variously talk of 50 or even more deaths. An Amnesty International report put the civilian death toll at over 70. More than 200 were injured, some of them seriously, and many with serious life-altering injuries. The enquiry report “recommended the immediate dismissal” of the murderous personnel and “initiation of criminal proceedings” to “ensure that justice is done and maximum possible punishment under the law of the land is awarded to such malignant and sick minded individuals”. Like scores of other massacres in Kashmir, justice eludes both — the victims and the perpetrators — of this massacre.

A week before the massacre, the Kashmir valley was plunged into deep crisis due to what is known as the Hazratbal siege. On 14 October, the Indian armed forces laid a siege to the sacred Hazratbal shrine, a white marbled dome structure with imposing minarets, on the banks of the famous Dal Lake. The shrine holds a lock of Prophet Muhammad (SAW), known as moe-e-muqaddas, making it the most revered monument in the province. It attracts millions of devotees annually, mainly on special occasions of the Islamic calendar, when people from everywhere come for a glimpse of the holy lock that is revealed from atop all the four minarets to afford a glance to the devotees thronging in all directions. Because of the siege, whole Kashmir was put under a total lockdown through curfews and spontaneous strikes, and resultant public demonstrations to press for lifting the military embargo.

The Bijbehara massacre remains one of the cruellest state-enacted murders. The official enquiry report establishes that it was thoroughly planned with active inputs from senior operational authorities. Out of the 22 martyrs from the town who are buried in the local martyr’s graveyard, previously a public park, 16 were teenagers, all of them students. Afroz Ahmed Zarger was the youngest of all — he was barely 12 years old and studying in the 5th class when the bullets snatched him. He wanted to become a doctor and was known to be a hard-working student. Most of the slain students had big dreams for their life. More than a dozen of them wanted to become medical doctors. Javed Ahmed Waza, 18, Shabir Ahmad Sheikh, 17, and Shabir Ahmad Shah, 18, all wanted to become medical doctors. So did Mukhtar Ahmed Ganaie, 18; Muhammad Iqbal Ganaie, 17; Altaf Hussain Sheikh, 15; Riyaz Ahmed Gatoo, 15; Abdul Rashid Vaid, 17; Mushtaq Ahmed Ganaie, 18; Muhammad Shafi Wagay, 18; and Muhammad Ashraf Zargar, 14. I fondly remember Arshid Hussain Tak, 17, whom I had known for a long time. He also wanted to be a doctor. Several months before the massacre, Arshid had carved his name on one of the concrete fence walls of the then public park that was converted to the martyr’s graveyard following the massacre. Arshid got a place within the grounds of his favourite park, albeit a berth for eternal rest. Several years later, his father, also a doctor, was killed in cold blood by the government sponsored militia gunmen.

A unique thing about the massacre, though by no means any reason for consolation, is that one of those murdered was a Hindu. Kamal Ji Koul was 17 years old and a student of 7th class. Like the rest of the townsfolk, he was part of the protest demonstration. I vividly remember my visit to his family in the old town and the pain and the disbelief of his parents was heart wrenching. According to local reports, his mother was left so heartbroken that she died within a couple of years after her son’s death — a phenomenon repeated in several such instances wherein mothers are unable to cope with the loss and perish soon after. Although the Kashmiri women have shown unprecedented resilience, they have been the worst sufferers of the brutality that remains under the control and direction of men of diverse ideologies and operating architectures.

Post script:

The official motives for the Hazratbal siege were thoroughly justifiable — the military wanted to flush out the armed militants who had made the shrine as their permanent base. However, the ensuing brutality to control the public sentiment turned the situation in favour of the holed up militants. Otherwise, most of the public viewed the militant presence inside the shrine as sacrilegious, as they had not only turned the complex into their operational base, but also a torture centre and an extortion hub. We could draw an analogy with Islamabad’s Lal Masjid before the Musharraf government ordered a full scale military crackdown. At the time, I remember there was growing public outrage against the militant activities inside the shrine, but it was often discussed in private for fear of militant reprisals, who were by no means any less violent.

Thankfully, after 32 days, the siege ended with the surrender of 65 holed up militants, mainly from the Jammu and Kashmir Liberation Front. They were given a safe passage amid rumours that millions of rupees also changed hands.

Sadly, the families of the victims — both slain and the injured — got nothing but a lifetime of lament.

Murtaza Shibli is a writer and consultant on Muslim issues in Europe and South Asia. He is also the editor of ‘7/7: Muslim Perspectives’, a book that explores the British Muslim reaction to the London bombings. Twitter: murtaza_shibli