“Two or three years after Partition, the governments of India and Pakistan decided that just as there had been a cordial exchange of prisoners, there should now be a similar exchange of lunatics. That is to say, Muslim lunatics housed in Indian asylums should be repatriated to Pakistan and Sikh and Hindu lunatics, in turn, handed over to India.

It’s hard to be sure of the wisdom of the idea. But in line with the wishes of intellectuals, a high-level conference was held, and at last, a date for the transfer was scheduled.

…

One cannot speak for the other side, but here in Lahore, a lively debate began at the lunatic asylum when news of the transfer broke out. When one Muslim lunatic – for twelve years a regular reader of Zamindar – was asked, ‘Maulvi saab, what is this Pakistan?’ he replied after careful deliberation, ‘an area in India where razor blades are manufactured.’ This explanation seemed to satisfy his friend.

…

but Bishen Singh would not relent. When they tried forcibly to send him across, he dug his swollen heels in at a point in the middle of the border, in such a way that it seemed no force was powerful enough to uproot him.

Excessive force was not used as he was harmless. He was simply left standing there while the rest of the exchange was completed.

Before the sun rose, a piercing scream broke from the throat of a rigid Bishen Singh, standing at attention. Several officers came to see the man, who had been on his legs day and night for fifteen years, lying face down on the ground. There, behind barbed wires, was India. Here, behind barbed wires, was Pakistan. In the middle, on a nameless piece of earth, lay Toba Tek Singh.” (From the story Toba Tek Singh)

Few other stories would rival Manto in bringing out the futility, irony and the pain of the partition of the Indian subcontinent. So it is with all the stories of Saadat Hasan Manto – the fewest possible details conveying all the necessary messages in the starkest possible manner. His frugality with words, his deep understanding of the vulnerability of human nature, and the poignancy of his themes, undoubtedly make him “The undisputed master of the Indian short story” (Salman Rushdie). His apparently Spartan short stories, couldn’t have been intrinsically philosophically more ornate.

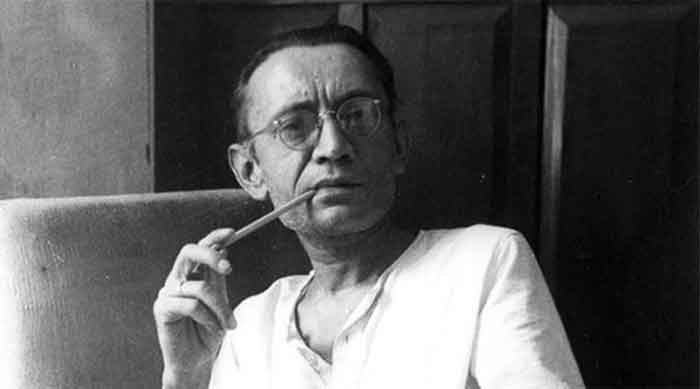

Saadat Hasan Manto (11 May 1912 – 18 January 1955) was born in Ludhiana, and was active in British India but decided to settle in Pakistan after the 1947 partition of India. Writing mainly in Urdu, he produced 22 collections of short stories, a novel, five series of radio plays, three collections of essays and two collections of personal sketches. He is acknowledged as one of the finest 20th century writers.

Manto was strongly opposed to the partition of India, which, to him, was an “overwhelming tragedy” and “maddeningly senseless”, as reflected in the opening quotes, that are taken from his story Toba Tek Singh (the opening story in the Selected Short Stories of Manto, translated from Urdu by Aatish Taseer, published by Penguin Books 2012). He never had any regards for stereotypical hierarchies or divisions in society. ”We’ve been hearing this for some time now — Save India from this, save it from that. The fact is that India needs to be saved from the people who say it should be saved” (Manto).

His life is as much remembered for the unforgettable stories it produced, as for the controversies that dogged him throughout. On his writing he often commented, “If you find my stories dirty, the society you are living in is dirty. With my stories, I only expose the truth”. Manto faced trial for obscenity in his writings, three times in British India before 1947 and three times in Pakistan after 1947.

But no one wants freedom of expression the way a writer does. Manto wrote in January 1952 (in between trials): “My mind was in a strange state. I couldn’t understand what I should do. Whether I should stop writing or carry on totally regardless of this scrutiny. Truth be told, it had left such a bad taste that I almost wished some place would be allotted to me where I could sit in one corner, away for some years from pens and ink wells; should thoughts arise in my mind, I would hang them at the gallows; and should an allotment not be possible, I could begin work as a black marketeer or start distilling illicit alcohol…”.

Manto’s translator, Taseer, writes in the introduction, “Given the extent to which Manto inhabits his material, there is something miraculous, as with Maupassant, whom Manto read and admired, that his range should have been so vast. He wrote about prostitution, religious superstition, adolescent anxiety, sex, the Partition of India and Bombay cinema in the 1930s and ’40s. They were the great themes of his time and though the stories are not forgiving, nor do they falsify the hard realities of India – there is something euphoric in the writing; it is easy to sense the writer’s joy in the newness and variety of life.”

For example, The Dog of Tithwal, the second story in this collection, dwells on the tragic fate of a dog who runs between two mountains on opposite sides of a valley, one of which is occupied by Pakistani soldiers, and the other by Indian soldiers, and both the armies claim the dog to be their own. In Ten Rupees, Manto depicts the carefreeness of a young prostitute, who loves travelling in cars with the breeze on her face like any young girl would. Blouse depicts the sexual arousal of a young boy working as a domestic help, by seeing young daughters of his master take measurements for stitching a blouse.

Ram Khilavan, once again delves deep into the havoc Partition played with the emotions and relations of people, who otherwise lived alongside each other happily. Taseer writes in his introduction, “In under ten pages of short sentences, each sprung like a cricket bat, he conveys what feels like an entire lifetime in Bombay. The thread of the story is a relationship between the narrator and his dhobi. When the narrator is poor and living in a ‘tiny room, destitute of even an electric light’, the dhobi, illiterate and warm-hearted, overlooks his unpaid bills. The narrator’s fortunes improve, he gets married, moves to a bigger place, the dhobi continues to come. One day the dhobi falls sick with alcohol poisoning and the narrator’s wife takes him in a car to the doctor, and so saves his life. The dhobi never forgets this kindness. Then Partition happens, the city is inflamed with Hindu-Muslim riots and the narrator decides to leave for Pakistan. On his last evening in Bombay, he goes to the dhobi to pick up his clothes.

The curfew hour is approaching and he finds himself surrounded by a murderous mob of drunken dhobis, of whom one is his. The dhobi, in a drunken haze, is about to attack the narrator when he recognizes him. The next day, the narrator’s last in Bombay, the dhobi brings the clothes as usual. He is overwhelmed with regret, but is never really able to express himself. A few hours later, the narrator leaves Bombay, never to return. The sense of loss and futility, told through this story of the little people one knew and has now to leave behind, is devastating. So much else is contained in the story’s compass: the nature of Partition violence; the kind of person who fell prey to it; how relationships in a city can change through such violence. The writer seems to be writing from deep within his material so that none of this is added externally, but is part of the fiction’s logic. The economy is not forced or done simply for the sake of economy; it feels necessary, an aspect of the story’s urgency.”

In the story Licence, Manto narrates how people fall victim to circumstances, and inspite of all efforts to stay honest and upright, societal norms can force people down the path of decadence. In the story, the protagonist Nesti (after her husband dies and leaves her with his horse and carriage, and Nesti tries to earn an honest living by driving it) says, ‘ “Sir, then take my horse and coach as well, but please tell me why women can’t drive coaches.

Women can grind mills and fill their stomachs. Women can carry rubble in baskets on their heads and make a living. Women can work in mines, sifting through pieces of coal to earn their daily bread. Why can’t I drive a coach? I know nothing else. The horse and carriage were my husband’s, why can’t I use them? How will I make ends meet? Milord, please have mercy. Why do you stop, me from hard, honest labour? What am I to do? Tell me?”

The officer replied: “Go to the bazaar and find yourself a spot. You’re sure to make more that way.” Hearing this, the real Nesti, the person within, was reduced to ashes. “Yes sir,” she answered softly and left.

She sold the horse and carriage for whatever she could get and went straight to Abu’s grave. For a moment, she stood next to it in silence. Her eyes were completely dry, like the blaze after a shower, robbing the earth of all its moisture. Her lips parted and she addressed the grave,

“Abu, your Nesti died today in the committee office.” With this, she went away. The next day she submitted her application. She was given a licence to sell her body.’

In the story For Freedom, the author speaks about his conviction that true revolution and protest cannot happen by suppressing the basic instincts of human beings. In Smell, the protagonist is enamoured by the smell of a working-class Marathi girl. “Randhir inhaled a strange smell coming from her body all night, it was at once foul and sweet-smelling, and he drank it in. From her armpits, her breasts, her hair, her back—from everywhere; it became part of every breath Randhir took. All night he thought, despite being so close to me, this Marathi girl would not feel nearly so close, were it not for this smell coming from her naked body. It had seeped into every groove of his mind, inhabiting all his old and new thoughts.

… In Randhir’s arms, lay a fair-skinned girl whose body was soft as dough mixed with milk and butter; from her sleeping body came the now tired scent of henna; to Randhir, it was as unpleasant as a man’s last breath, sour as a belch. Discoloured. Sad. Joyless.

Randhir looked at the girl who lay in his arms as one looks at curdled milk, with its lifeless white lumps afloat in pallid water. In the same way, this girl’s womanliness left him cold. His mind and body were still consumed by the smell that came naturally from the Marathi girl; the smell that was many times more subtle and pleasurable than that of henna; that he had not been afraid to inhale, that had entered him of its own accord and realized its true purpose.

Randhir made one last effort to touch this girl’s milky white body. But he felt no trembling. His brand-new wife, who was the daughter of a first class magistrate and had attained a BA, who was the heartthrob of so many boys in her college, did not quicken his pulse. In the deathly scent of henna, he searched for the smell that in those same days of rain, when in an open window the peepal’s leaves were washed and wet, he had inhaled from the dirty body of a Marathi girl.”

In the sheer vastness of his variety, the sharpness of his understanding, in the sting of his irony, and in the sympathy of his understanding, lies the inimitable Manto. Unfortunately however, Manto lies mostly forgotten, and only half-heartedly so, if remembered, in India. So Taseer writes, “India must now reclaim men like Manto. In Pakistan, Manto’s world, crowded with Hindus, Sikhs and Muslims, would feel very foreign. It is only in India, still plural, not symmetrically Hindu, that it continues to have relevance. His eye could only have been an Indian eye, sensitive to surprising detail, compulsively aware of Indian plurality, sympathetic to people trapped in their circumstances, here pointing to a particular Hindu festival, there imitating Bombay street dialect.

Writers rarely set out to be national writers. They need small, intimate worlds, full of details; the macro scale of countries, especially those as wide and various as India, cannot be their direct material. Cities, neighbourhoods, sometimes a single street, provide the gritty detail in which a larger architecture can become visible. For Manto, this city, as Dublin was for Joyce and Chicago for Bellow, was Bombay. He was not an Indian or a Pakistani writer as much as he was a Bombay writer, and more than India, the city of Bombay must reclaim Manto.”

He died on January 18, 1955 in Lahore at the age of forty-two. Manto is buried in Miani Saheb graveyard in Lahore. In 1954 he composed his own epitaph:

Here lies Saadat Hasan Manto. With him lie buried all the arts and mysteries of short story writing . . . Under tons of earth he lies, wondering who of the two is the greater short story writer: God or he.

However, on the insistence of his family it was replaced by an alternative epitaph on his grave, which was also authored by him, inspired by a couplet from Ghalib:

This is the grave of Saadat Hasan Manto, who still thinks his name was not the repeated word on the tablet of time.” (Wikipedia)

A contemporary and very close friend of Manto was Ismat Chugtai, a very acclaimed Urdu writer herself. But while Manto decided to settle in Pakistan after the Partition, Chugtai decided to remain in India. Ismat Chughtai (21 August 1915 – 24 October 1991) “wrote extensively on themes including female sexuality and femininity, middle-class gentility, and class conflict, often from a Marxist perspective. With a style characterised by literary realism, Chughtai established herself as a significant voice in the Urdu literature of the twentieth century, and in 1976 was awarded the Padma Shri by the Government of India.” (Wikipedia)

Chugtai’s writings were no less stirring than Manto’s and often left entire strata of the Muslim world in utter disarray. No wonder a collection of her short stories (translated from Urdu into English by M Asaduddin, Penguin Books, 2009) is titled “Lifting the veil”. Manto and Chugtai often faced trials for obscenity together. Asaduddin in his introduction writes, “But the story that Ismat Chughtai is best known for is ‘The Quilt’ (‘Lihaaf’), which jolted the Urdu reading public out of their complacency by daringly depicting female sexuality in a manner not attempted before in modern Indian literature. This treatment of homosexuality and lesbianism lends itself to fruitful feminist readings even as it provokes indignant reactions among the conservative public. But Chughtai is speaking of a very specific situation in this story, not making general statements on acceptability of sexual preferences. This is why the begum is also a figure of fear for the child narrator. The greatest strength of the story lies in its subtle combination of the facetious and the serious. Chughtai’s use of a naïve child narrator helps her to treat her subject with great freedom. The child uninhibitedly recounts events as she remembers them, not pressured by any social taboos. The dexterous use of the quilt as both object and metaphor creates the ambiguity and tension that arises between calm exteriors and treacherous undercurrents.”

Quoting from the story The Quilt in this collection: “There was that peculiar noise again. In the dark Begum Jaan’s quilt was once again swaying like an elephant. Allah! Ah! … I moaned in a feeble voice. The elephant inside the quilt heaved up and then sat down. I was mute. The elephant started to sway again. I was scared stiff. But I had resolved to switch on the light that night, come what may. The elephant started shaking once again, and it seemed as though it was trying to squat. There was the sound of someone smacking her lips, as though savouring a tasty pickle. Now I understood! Begum Jaan had not eaten anything the whole day. And Rabbu, the witch, was a notorious glutton. She must be polishing off some goodies. Flaring my nostrils I inhaled deeply. There was only the scent of attar, sandalwood and henna, nothing else.

Once again the quilt started swinging. I tried to lie still, but the quilt began to assume such grotesque shapes that I was shaken. It seemed as though a large frog was inflating itself noisily and was about to leap on to me.

‘Aa… Ammi. I whimpered. No one paid any heed. The quilt crept into my brain and began to grow larger. I stretched my leg nervously to the other side of the bed, groped for the switch and turned the light on. The elephant somersaulted inside the quilt which deflated immediately. During the somersault, a corner of the quilt rose by almost a foot …

Good God! I gasped and sank deeper into my bed.”

In the story In the name of those married women…, Chugtai recounts her experiences when she and Manto were tried for obscenity. She said how her entire writing career seemed burdened by this one story ‘Lihaaf’ (Quilt), though in the end when she met ‘Begum’, she had hugged her and said her story was instrumental in giving her the courage to divorce her previous husband and marry again, and she now has a son and is very happy. So Chugtai somehow feels that Lihaaf has served a greater purpose in life. In the end she writes, “… Faiz’s verse:

In the name of those married women

whose decked-up bodies

atrophied on loveless,

deceitful beds …

And I wondered, Where is the Ideal Indian Woman?

Sita, the embodiment of purity, whose lotus-like feet cooled the flames on which she had to walk.

Mira Bai, who put her arms around God himself.

Savitri, who snatched away her husband’s life from the Angel of Death.

And Razia Sultana, who spurned great emperors and joined her destiny with that of a Moorish slave.

Is she getting suffocated today under the lihaaf?

Or, is she playing Holi with her own blood in Faras Road?”

The story, My Friend, My Enemy, is again a personal recollection of her tumultuous friendship with Manto, now flowing, now ebbing, especially after Manto’s decision to migrate to Pakistan. She writes, “I learnt that a lawsuit had been filed against him and he had been thrown in jail. All sat idle and impassive. No one protested against it. In fact, the general feeling was, ‘Good that he has been thrown in jail. Now he’ll come to his senses!’ There was no conference, no meeting; no resolution was passed.

Then came the news that his brain was giving trouble and that his relatives had put him into an asylum. But one day there came a letter from Manto, a perfectly sensible one.

‘I’m absolutely fine. It’ll be great if you can call me to Bombay using the good offices of Mukherjee.’ After that, there was silence for a long period… I got scared of any news from Manto. Visitors from Pakistan did not carry any good news about him. He had become a confirmed alcoholic and borrowed money from everyone. Newspaper owners got him to write articles in their presence and then paid him. If anyone paid him in advance, he just blew up the money.

In his last letter to me, Manto had asked me to write an article on him. “I’ll write the article only after your death”, I had blurted out the inauspicious words involuntarily.

And now I’m writing after his death. Not only Manto but also a lot that had grown between us had died a long time ago. Now there’s just this heartache. I don’t know why I feel this ache. Is it because Manto is dead and I’m still alive? …

There is a voice in my heart that says that I have a hand in Manto’s premature death. The invisible bloodstains that smear my conscience can be seen only by my heart. The world that drove him to death is my world as well. It was his turn today. Tomorrow it will be mine. Then people will mourn my death. They will worry no end about my children.

They will collect money for a gathering to commemorate me and fail to turn up for the meeting for lack of time. Time will pass, the burden of sorrow will gradually lighten, and then they will forget everything.”

Vocation, has a very reflective tone, where a young woman, the protagonist of the story, reflects on really how noble other professions are compared to prostitution. She deeply contemplates, “For instance, it seemed to me that the sethani tempted her clients with her get-up for the sake of livelihood. I also do the same-making myself presentable I go to the court of my clients. The only difference was that my intellect was a squeezed-out sugar cane while the sethani was a pitcherful of nectar. I sold my brain and she her body! The value of my brain was equal to that of a second-hand tyre, that is, seventy rupees. And the sethani? She earned much more in one sensuous gesture than my father, a highly placed officer of the British government, did in his whole life. Both of us were sitting in the marketplace displaying our wares. Different wares, but the objective was the same. What was the worth of my squeezed-up brain before her stately physique? A mere paan-biri kiosk in front of a cricket club! I was sure to be beaten. The thought made me burn with jealousy. People feel pity for courtesans and endeavour to improve their lot — no, they should not completely disappear – but those living poorly should live better! Their shabby clothes be replaced by sparkling ones! Their dwellings on drains and sewers be transferred to Marine Drive! The clients should come, but not so many that they can’t take good care of! On the other hand, no one seems to care if our salary goes down year after year. Let the number of students, all troublemakers, increase twofold; the headmistress sucks you dry, the clerks in the office claw you and the committee members swallow you up—no one gives a damn! Lady teachers are moulding children’s minds just as courtesans are providing succour to ‘orphans’. Both are doing their duty-then why this discrimination?”

In the story Tiny’s Granny, (Translated by Ralph Russell), Chugtai deeply sympathises with the have-nots of this world, where Tiny’s Granny, the protagonist represents such unfortunate people of the world. “There was no sorrow in the world, no humiliation, no disgrace, which Fate had not brought to Granny. When her husband died and her bangles were broken, Granny had thought she had not many more days to live; … And when Tiny brought disgrace upon her and ran away, Granny had thought that this was the death blow.

From the day of her birth onwards, every conceivable illness had assailed her. Smallpox had left its marks upon her face. Every year at some festival she would contract severe diarrhoea.

Her fingers were worn to the bone by years of cleaning up other people’s filth, and she had scoured pots and pans until her hands were all pitted and marked. Some time every year she would fall down the stairs in the dark, take to bed for a day or two and then start dragging herself about again.

In her last birth Granny surely must have been a dog tick; that’s why she was so hard to kill. It seemed as though death always gave her a wide berth.

…

On Judgement Day, the trumpet sounded, and Granny woke with a start and got up coughing and clearing her throat, as though her ears had caught the sound of free food being doled out … Cursing and swearing at the angels, she dragged herself somehow or other doubled up as she was over the Bridge of Sirat and burst into the presence of God, the All Powerful and All Kind… And God, beholding the degradation of humanity, bowed His head in shame and wept tears, and those divine tears of blood fell upon Granny’s rough grave, and bright red poppies sprang up there and began to dance in the breeze.”

Both Manto’s and Chugtai’s stories are extremely honest, and powerful and reflect on human nature and its shortcomings in myriad hues of life and its circumstances. The stories leave one with questions about the sanity of institutions, societal norms, gender stereotypes and barricades, the expectations and possibilities in relationships, decisions of the powers-that-be, the overarching presence of goodness and love, and the infinite hope that dwells in smallest of gestures. Far from having any moralistic and judgemental undertones, the stories draw heavily from real life in all their often sad and dark desires and perceptions.

Manto and Chugtai are no more amongst us, but they wrap us in their yarn of words ever more vibrantly and forcefully, especially in these troubled times. Leading us, while letting us fall and stumble, often picking us up and nudging us, shoving us from bittersweet truths and ironies, sometimes darkening our vision, while at times blinding it with a burst of light, making us laugh and cry, and in the end helping us feel one with millions of others across times and spaces who are all sharing this amazing journey of life with us. As Tagore unforgettably wrote of short stories, even when the stories end, they never do.

Soumyanetra Munshi, Associate Professor, Economic Research Unit, Indian Statistical Institute Kolkata