(Wisdom-King Achala: The Unshakeable)

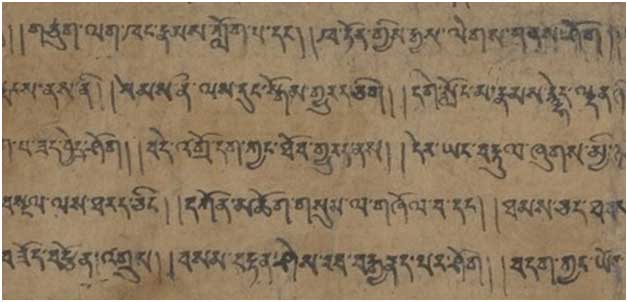

Presented here are some tales and some verses by Bhusukupa, mystic, poet, who lived in the eastern parts of the Indian subcontinent around a millennium ago. Lovers of Bangla literature remember him as the poet who wrote seven and a half poems of the Chawrjyapawd collection that contains verses that speak of the Tantric SahajaYana or the Easy Vehicle philosophies and are considered as the earliest examples of Bangla literature.

The manuscript containing the Chawrjyapawd verses was re-discovered by modernity from the Royal Durbar Library of Kathmandu by Haraprasad Shasti (1853-1931), who, on behalf of the Asiatic Society, had visited Nepal thrice – twice between 1897-98 and once in 1906-07 – to look for ‘Oriental’ manuscripts.

This manuscript, along with three other manuscripts containing SahajaYana verses, viz.

- the Sahajanmay Panjika as written by Sarahapa (8th-9th/ 10th-11th CE) and annotated in Sanskrit by Tantric Advay Vajra (10th-11th CE),

- the DNohakosh of Kanhopa as annotated in Sanskrit by Mekhala the Elder of the Two Headless Sisters (Mekhla and her sister Kankhala, who were Tantric disciples of Guru Krishnacharya, have together been deified in the hitherto extant Lokayat pantheon of the eastern subcontinent as Chhinnamasta – the Sever-Headed Goddess),

(Chhinnamasta Vajrayogini – the Sever-Headed Goddess)

and

iii. the Dakarnawb which means Wizards’ Ocean has been written by anonymous wizards and witches belonging to the fold of what then had spread across Bengal as Tantric Buddhism and survives till date as Vajrayana or the Thunder Vehicle, or as Tibetan Buddhism –

were published by the Bongiyo Shahityo Porishawd in 1916 as ‘Hajar Bawchhor Purano Bangala Bhasha-ey Bouddho Gaan o DNoha’, meaning, ‘Buddhist Songs and Dohas written in One Thousand Year Old Bangla Language’.

Together, these manuscripts also form a part of the Bstan ‘Gyur resources of Vajrayana Buddhism, though, unlike most other literary resources contained in the Bstan ‘Gyur, these exist not in their Tibetan translation but as they were written in original, in the language that claims common ancestry to Bangla, Ahomiya, Syllheti, Odiya, Angika, Magahi, Brajabuli and Bhojpuri.

Haraprasad had named this proto-language as the ‘Twilight’ language, because, as he writes in his introduction to the 1916 book, it is a ‘language of light and darkness’. The validity of this nomenclature by Haraprasad was challenged by Vidhushekhar Shastri and then by Mircea Eliade (1971), but one curious historical wisdom comes to light in this context. It is that the language used in the four books in the collection and other similar books such as the King, the Queen and the People DNoha collections and the Ka-kha-sya DNoha-s of Sarahapa, several Tantric Sahajayana, Chakrasamvarayana and Kalchakrayana books, especially those in the Bstan ‘Gyur collections as those written by the Siddhacharyas, were all written in a sort of coded or secret language where each word and/or phrase, or idiom, or any other expressive element contained therein have multiple folds of meanings. The Sahajiya songs sung by the Baul-Fakir mystic minstrels of Bengal still follow this technique of using multiple, and often endless layers and folds of meanings, all intertwined into a semantic wonderland of literature and philosophy, as does many mantras in many of the Tantras as present in the secretive Agams and the Nigams. The reason behind using such codes is, in all probability, to ensure non-destruction and/or cooption by the casteist Brahmins who were to have a re-rise in Bengal through the Sena dynasty, soon after the times when these songs were written.

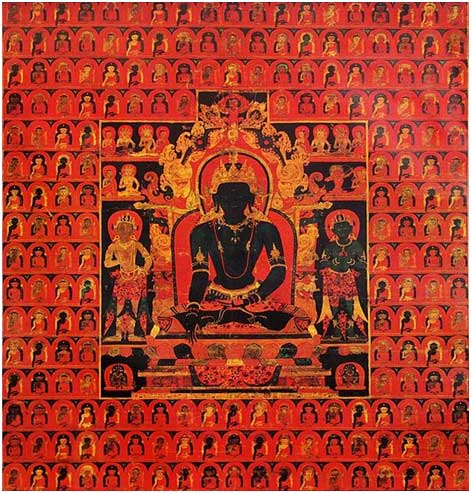

(Dhyani-Buddha and Guhya-Samaja or Secret-Society deity Akshobha – literally, The One Who Never Gets Angry as painted in late 13th CE, from whose name derives the Baul-Fakir term ‘Khyapa’. His mudra is bhumi-sparsha for the finger/s of his right hand always touches the ground)

That it was a secret or coded language was acknowledged by Eliade (1971). Post Eliade scholars such as Keith Dowman, Judith Simmers-Brown et al, at different times in the 1980s and 1990s when Buddhist studies were fledgling discourses in America, had conceded to the validity of the term ‘Twilight Language’. Some of their works adorn the public domain while the rest adorn the online portals of knowledge as references and footnotes.

Haraprasad Shasri had written an Introduction and short biographical notes on the poets for the 1916 publication. He had also created a glossary containing all the ‘Twilight’ language words of all the four manuscripts with their corresponding Bangla meanings. Moreover, Taraprasanna Bhattacharya had written explanatory Bangla notes on each of the Chawrjya poems based on the Sanskrit explanatory notes by Munidatta or Luipa, also known as Meenanath or Matsyendranath in mystic Nath traditions. Several modern-Bangla translations of the 47 and a half Chawrjya poems that appear in the Shahityo Porishawd publication exists, a few being also in present in the public domain.

Before learning about the life of Bhusukupa from the texts of Haraprasad, let us look into the radiant, misty euphoria that SahajaYana or the Easy Vehicle encompasses. For me, the best entry-point to the Easy Path is perhaps the penultimate line from Sarhapa’s Sahajanmay Panjika:

“…para-apaNa meiN bhatti karu sa’al nirantar Buddha…”

meaning,

“…build no illusions between self and the others, we’re all Buddha

– endless – …”

Drawing from the Madhyamaka philosophies of 1st-2nd CE Mahayana scholar Nagarjuna, the negation of all binaries to attain a state of absolute void or Shunya, was the quest that the Sahajayana school of Buddhism had envisioned through the materialist praxis of kaya-sadhana (the body praxis), through the ontology of deho-tawtto or the body-theory. Most of the Siddhacharyas venerated till date both in Vajrayana and the Nath Path had acknowledged this praxis of the Easy. The body-elements of SahajaYana are akin to those of the Lokayatic philosophers, and as such both such schools have been noted for their extreme materialist heterodoxy and atheism. For them, as a Bangla adage on this wisdom goes, ‘… ja nei bhanDey, ta nei bhanDey…’, implying, ‘…what is absent from the (body-) vessel is absent from the (universe-) vessel…’.

It was not just the imminent Brahminnical oppression spearheaded by the followers of Shankaracharya, his Guru Govindacharya and Govindacharya’s Guru GouRpa – who had interposed and replaced the ‘shunya’ or the Void from the Madhyamaka beliefs of Unitarian Voidism that had become popular among the Buddhist masses of the subcontinent in the millennium before the last one with ‘Vedanta’ or the Upanishads, thereby seeking to re-affirm the supremacy of the Brahminnical caste-order over the Buddhist casteless one – but also a specific philosophical urge, that had made the earliest Sahajiya bards such as Bhusukupa and Sarahapa use codes and crypts and thus leave multiple layers of interpretation open in their verses. Let us look at this urge of philosophy:

According to the body-praxis of the Easy Vehicle Tantrics, speech is of four types –

1) What we speak when awake,

2) What we speak in dreams,

3) What we speak in deep dreamless sleep, and

4) That which is beyond all speech – Paravaak

It was this fourth realm of speech that the Sahajiya Tantrics sought to explain and express through their songs. Thus, metaphors, allegories and multiple layers of connotations were necessary – making use of which the Tantric bards wrote their songs seeking to provide to the faithful seekers a blue-print of the path to Nirvana – to attainment of the Void by voyaging through humanly senses. Thus, crypts were necessary to explain what cannot be explained by ordinary speech or language – to tell of the Anuttar that lies beyond all linguistic mores and modes of expression.

The term Anuttar-Dharma has often been used in reference to the Sahajiya i.e., the Easy Path. One of the Chawrjya poets, viz., ChaTilpa, refers to himself as Anuttar Swamy. Anuttar means, that which has no answer. The challenge for the Sahajiya bards who had written the Chawrjya verses was to write of what is beyond all speech, of the wisdom of silence no question regarding which can be answered. How did they rise to this challenge?

As Kanhopa writes in Verse no. 40 of the Chawrjya poems,

jo maN-go-awr alajala/

agampothee iShTmala//

vaN kaiseyN sahaj bolwa ja-aw/

ka-aw-baak chi-aw jasu N sama-aw//

aley guru u-esi sees/

baak pathateet kahib kees//

jetoi boli tetabi Taal

guru bob se sees kaal//

vaNoi kahno jiN-raw-awN bi kaisa/

kaaley bob sambohi-aw jaisa//

Drawing from Twilight to Bangla the Glossary as appended with the 1916 publication read with the Bangla translations of the Sanskrit notes of Munidatta, this poem can in expressed in English like this:

‘Scriptures, chants, crypts

Books of Wisdom

Garland of God

it’s all magic!

it all flickers!

a thousand little lamps

the multitudes

their bodies, words, minds –

can’t hold this magic,

can’t hold real wisdom in these

The Wisdom can’t be spoken of,

be written about.

Human systems of communication

have not evolved enough

to express what Easy means in the truest sense

The guru who speaks of Ease

to the disciple –

is a false guru

for true Ease can’t be spoken of,

be written about.

Wizard of Thunder teaches Easy Wisdom

he can’t speak

he has no answers

his students have no questions

the students can’t hear

And Kanho speaks through this song –

the jewel of life shines on

the emerald of bliss shows the light

to the fourth realm – the one of Easy delight

Guru Thunder teaches the Easy ways

like folks who can’t speak talk to folks who can’t hear.’

On another day we shall embark upon a voyage in search of Kanhopa. For today, let us stay with Bhusukupa, with what Haraprasad has to say about him in his 1916 publication, what subsequent scholarship has to found out over the past one hundred years, and with what Bhusukupa had written that makes him stand as one of the earliest bards of Bangla, Syllheti, Ahomiya, Odiya, Angika, Bhojpuri, Brajabuli and Magahi literatures.

First, the following texts about Bhusukupa are translated from the ‘Mouthpiece’ or Mukho-bawndho as was written by Haraprasad in the 1916 publication of Bongiyo Shahityo Porishawd:

“In locker number 9990 of the manuscript-room of the Asiatic Society there lie three palm-leaf parchments. Together, those contain a biography of Shantideva. It is written in the old Newari script. From the nature of the letters it seems like it was written in the 14th century AD.

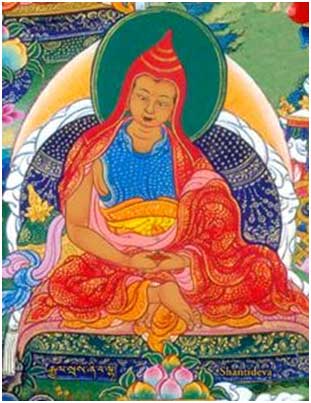

(Shantideva)

Shantideva was a prince. The name of the country where he belonged to cannot be read from the script. His father, the king, was ManjuVerma. Taranath had said that the kingdom was that of Saurashtra. Even Cecil Bendall (1856-1906) seems to be of the same opinion. However, I do not think this is correct. I shall explain latter why.

ManjuVerma wished to make Shanti his heir and successor to the royal throne. There used to be a ritual celebration to mark the entry of the prince into his inheritance to state power. On the day when such rites of passage were to be conducted in the imperial courtyard, the queen came out in protest. She told her son Shanti –

‘If you become the successor and then the king, with passage of time you shall drown in sin. I wish for your happiness, I want you to move forward in life; so I tell this to you, son, that you must leave these lofty vaults of power and dominance and venture out into the country where the Buddha is and where the Bodhisattvas are. There you shall find a wizard named ManjuVajra. Make him your Master. You shall find your path.’

Hearing this, Shanti rode a green horse and set out for the faraway lands of Buddha and the Bodhisatvas. He left the kingdom and rode on and on for days on end – without stopping even for food or sleep. And then one day, as he was riding through a deep forest, a beautiful girl came by. She held the reins of his green horse and told him to alight. Shanti obeyed. She gave him cool water to drink and delicious mutton to eat. Conversations ensued. She told Shanti that she was a disciple of ManjuVajraSamadhi. This news startled Shanti. He told her –

‘I have come to become a pupil to your Master!’

Hearing this, she took him to ManjuVajra. Shanti became his student. He learned from his Master for twelve years. He learned the wisdom of MonjuShree – the Bodhisattva of Zen. As those twelve years passed by, his Guru spoke thus to him:

‘Go to the Middle Country.’

Shanti went to the Middle Country and became the Rout/Raut of the King of Magadha. Rout/Raut means a General . The word ‘Raut’ is not in use now. The people from the Gawndhobonik caste of Bengal whose profession by birth was to trade in perfumes and spices used to have four ashramas or schools. One of those is that of the Raut. The traders belonging to the Raut-ashrama used to sell spices from their tents, mostly in barracks. Many big cities of the past used to have localities designated solely for the Rauts.

Shanti became a Raut and he changed his name to Achalasena/Achal Sen/Awchawl-Shen . He had carved a sword for himself made of wood from the sacred cedar tree. With time and by dint of sheer hard work and sweet behavior he became well-liked by the king. The other Rauts of the nobility thus grew jealous of him. One day, they came to know that the sword of Awchal-Shen had been crafted out of wood. They told of this to the king. Thus the king, one day, declared that he would examine the swords of all his generals.

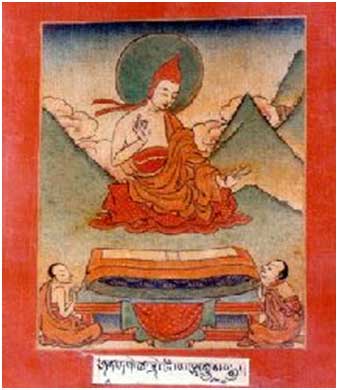

(Achal, painting from 12th CE)

The other generals obeyed but Achal, whose name means Immovable, stood true to his name and refused, saying that his sword holds such power that the king would be blinded if he dares to look at it. He insisted that the king cover one of his eyes before he sees the sword, for else he shall lose vision in both. Curious, the king covered one of his eyes as Achal took his wooden sword out. The king lost vision in the eye which he had kept uncovered. The king was happy. He spoke words of praise about Achal. But Achal had made his mind up. He was not to stay there as a Raut anymore. Time had come for him to leave. He dashed his wooden sword against a piece of rock, and, having thus shattered it to pieces, he went away from the kingdom of Magadha in the Middle Country and reached the famed university of Nalanda – an institute where much sacred wisdom was gathered and imparted. Thus began his life as a philosopher and a writer.

He built a tiny hut made of leaves stitched together at a nondescript corner of the sprawling university-town of Nalanda and began to stay there. He would listen to explanations of the Tripitaka canons as the learned scholars of Nalanda would come up with, and he would practice Yoga. He was known for being calm and ever at peace. He would remain silent and keep to himself. His manners were gentle and polite. Thus, in Nalanda, he came to be known as Shantideva – Mr. Peace. He was bestowed with yet another title from the Sangha at Nalanda – Bhusuku. This is an acronym derived from a sloka –

“bhunjanopi pravaswaroh suptopi kuTing gatopi tadeveti bhusukusamadhi-samapannatwat bhusukunamkhyating sanghehapi”

Meaning: His body would be bright when he would eat, it would be bright when he would sleep, and it would also be bright when he would sit inside his hut

Days passed by. True to his polite nature, he did not engage in many conversations as he went about his daily activities maintaining his calm demenour and gentle composure. But as it is with every institute of learning, a few the young students of Nalanda sought to play a few pranks on him. Some took his silence for ignorance and decided to try to make him speak at one of the many occasions and events that were organized throughout the year by the Sangha of Nalanda.

One such occasion was about to arrive. It was the eighth night of the moon’s fortnightly journey from blankness to full-moon radiance of the midsummer month of JoishThyo . There was a custom prevalent in Nalanda where sacred scriptures and treatises were read and explained in this summer night every year. There was a big inn – a Dharmashala – to the North East of the main monastery-building at Nalanda. Each year, the learned and the curious would gather there on that night, and the inn would be decked up for this occasion.

That year, as the scholars, the pupils and all the listeners had gathered and the readings, debates and discussions were set to ensue, some of the students began to make such clamour:

‘Shantideva, you must speak today! We want to listen to you’.

Shanti was not willing, but the students stood stubbornly insistent. They almost dragged him to the stage that was raised for the speakers. The students had thought that he will not be able to speak, and thus they shall get their chance to jeer at him in public.

Shantideva stood sombre and uttered:

‘kim arshang paThami artharshang ba.’

meaning,

Which readings are Arsh and which ones are Artharsh?

The learned and the wise who had gathered were struck speechless. They knew of the Arsh, but they had not heard of the Artharsh . Bewildered, they asked:

‘so what is the difference between these two?’

Shanti said:

‘Those who possess the wisdom of the Utmost Essence they are the sages – the Rishis – they are the Buddha and the Jina. What they say is Arsh – utterances of the sages. But here you may ask – ‘how can the canons and advices of Subhuti and the other disciples be Arsh?’ For that, Prince Maitreya has this to say:

‘yadarthavaddharmapadopsamhitam tridhatusamkleshnivarhaNam vachah

vabey vabechchantamnushamsadarshakam tadwat kramasham vipareetamanyatha’

Thus, what the learned learn from the Arsh books – the essences they draw from those – that is artharsh, whereas the works of disciples such as Subhuti et al constitute the Arsh – because the Buddha rests at the foundations of such works.

At this point the learned pundits that were listening spoke out:

‘We have heard much of Arsh. We wish to hear some Artharsh from you’

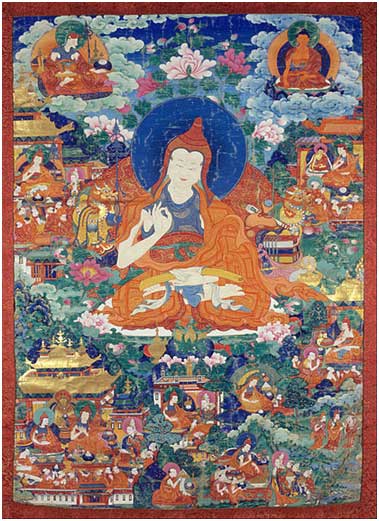

By that time of his stay at Nalanda, Shantideva had written three books – Bodhicharyavatar, Shiksha-Samuccaya and Sutra Samuccaya.

(Scroll From Shantideva’s Bodhicharyavatar)

Shanti stayed calm, composed and in tranquil Zen for a while. Then, he began reading from the Bodhicharyavatar. The language used and the manner in which he read it was soft, deep and gentle – his voice rang like strums of a harp – and the senses that the words conveyed were deep, sweet and pithy. Awed, the pundits began to listen in sheer silence; the pupils who had earlier almost dragged him to the stage were now filled with reverence. The reading went on through this rapt silence that prevailed. As Shanti was fathoming the depths of the theories of the Greater Vehicle Path, he uttered the following words with the same focused composure and sonorous profundity that marked his nature –

‘yada na bhavo nabhavo mateh santishThateh purah

tadanyagatyabhavena nirlamboh prasahamyati’

As he had set about explaining the meaning of this sloka, the gates of heaven opened up and bright light poured is as Manjushri, whose body was glowing bright in the aura of godliness, descended – riding on his airborne chariot, which, too, was made out of the colours of light. The god came down his chariot and embraced Shanti with love. He held Shanti by the arm and welcomed him onto his radiant, airborne vehicle. Together, they went to heaven.

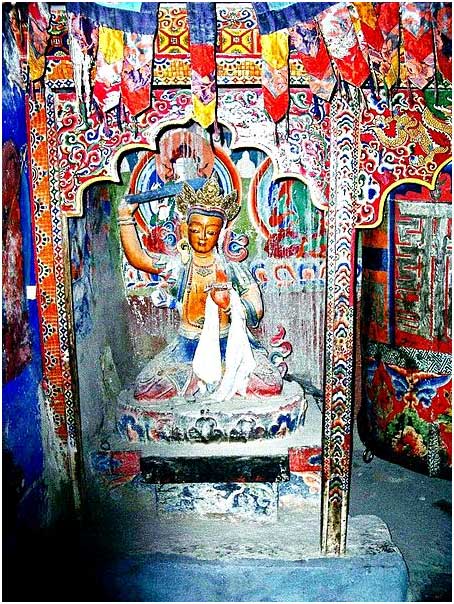

(Idol of deity Manjushri at Spiti Gompha, Himachal Pradesh, India)

The next day, the scholars of Nalanda went to the hut that Shanti had built. They found the manuscripts of Bodhicharyavatar, Shiksha-Samuccaya and Sutra Samuccaya and published the same on behalf of Nalanda. Two of these manuscripts have been found and have since been printed – but the one referred to as his Sutra Samuccaya remains yet to be rediscovered by modernity. The scriptures reveal that Shantideva and Bhusuku was the same person.

Like the lyrics of Sarahapa, some songs written by Bhusukupa have also been found in the manuscript of Charya-Charyo-Vinishchay. However, whether the Bhusuku who had written these songs was same as the one who had written those books is doubtful – because the books of Shantideva alias Bhusuku speak of the Mahayana Path whereas the Chawrjya-verses by Bhusukupa speak of the Easy Path.”

The first part of Shantideva’s life, especially her mother’s staunch refusal to his imperial future, bears similarities with the Nath tale of Gyan-Dakini or Wisdom-Witch Queen Moynamoti who had similarly prevented her son Govind Chandra from ascending the throne, on the advice of her Guru Jalandharipa. The Nath and Vajrayana traditions have many overlaps.

(Idol of deity Gyan-Dakini or Wisdom-Witch)

Haraprasad, in one part of his Introduction to the 1916 publication of the Chawrjyapawd, says that ‘The scriptures reveal that Shantideva and Bhusuku was the same person…’, whereas, in very next paragraph, he opines that Shantideva and Bhusukupa might have been different persons. Both possibilities lie open through different windows of historical chronology. Shantideva, the celebrated Mahayana scholar and the author of Bodhicharyavatar, Sikkha Samucchaya etc., whose life has been extensively researched upon by 17th century Tibetan monk Taranath, had hailed from the 7th-8th Centuries AD, whereas Bhusukupa belonged to the times when Sahajayana had developed as a philosophy, which implies that he was either a contemporary of Luipa aka Minanath (10th-11th CE) or he belonged to times after Luipa. This is because Luipa or Minanath is usually accredited as the founder of the Easy Vehicle school.

However, there exists another line of thought, as affirmed by Rahul Sankrityayan in his introduction to the 1957 publication of Sarahapa’s Dohakosh by Bihar Rashtrabhasha Parishad, that Sarahapa and not Luipa is the Adi Guru or the First Master of the Sahajayana monastic order. Sarahapa, according to most historical records, had hailed from the 7th-8th centuries AD. If that be the case, then the possibility of Shantideva and Bhusukupa as being the same persons cannot be ruled out. The constant reference to himself as Rautu, which implies a prince (rajputra) as well as someone belonging to either the pastoral Raut caste or the other caste bearing the same name whose the lineage-mandated profession is to sell perfumes and spices to the armies as made by Bhusuku in his poems that appear in the Chawrjya collection might also indicate that he is none other than Shantideva.

The second contention also bears plausibility through the annals of recorded Buddhist history of the Nalanda monastery, where Shantideva was disliked by other monks and scholars because of his laziness and reluctance to attend classes, so much so that it came to be said about Shanti is that he stays bright all day through his works that comprise of eating (bhunjanopi), sleeping (suptopi) and sitting inside his hut (kuting gatopi), and thus, in mockery towards his laze, the acronymical epithet Bhu-su-ku came to be bestowed upon him.

It might also have been so that Bhusuku was a title that flowed down the Guru-disciple lineages across a couple of centuries and thus Shantideva and the Bhusukupa might also have been different persons who bore the same acronymical title during their respective times. Without further ado on probabilities, let us veer back to Haraprasad’s text in his introduction to the Bangla book of 1916. He goes on saying:

“There exists yet another incomplete seven-page manuscript of verses on the Easy Path as written by Bhusukupa, numbered 4801, in the collection of the Asiatic Society. It contains canons on eating and on sleeping, on building huts – and is thus a set of rules to be followed by the Easy Path people. This Manuscript No. 4801 of the Asiatic Society consisting of the unfinished seven (palm-leaf) page/scroll scripture as written by Bhusukupa also contains rules on drinking alcohol and its assorted paraphernalia. It contains Bengali rhymes and the letters of the manuscript are very ancient.

One of the poems goes as follows:

Robi-kawla melawho, Shoshikawla barawho, beNi baaT bawhawnto

toRaha samasta samarasa jau na jaytey kagaN jagfawla khaye

(Haraprasad Shashtri, in his Mouthpiece, does not translate the poem into modern Bangla. However, taking help from the glossary of terms provided by him at the end of the book Hajar Bawtshor Puratawn Bangala Bhasha-ey Bouddho Gaan o DNoha (Buddhist Songs and Dohas written in a Thousand Year Old Bangla Language) of which this text is a Mouthpiece, a rough translation of it will be as follows:)

The art of the sun unites, the art of the moon rises,

the two

their union

their duality

make the roads flow by

and swell

Broken, they who love it all the same –

can’t go anywhere

– ravens eat the fruit of the world

Another one goes thus:

‘Ombu pasartu chandan barho awkkoheTh kamala kori shayana awkko

Surchapi shashi samarasa jaye Raut boley jaramarana bhawey

beyadanDa chaudda charjyaha surkaye cchaRi na jaayi

so dur yogi na janaha khoj guru ninda kori yoga’

Meaning, roughly:

Trade in water, perfumed sandals rise,

strange lotus in strange bed

The moon rides on music and loves it all the same

The sun and the moon love it all the same

Shanti,

the General,

the Prince,

perfume-trader of the camps,

Bhusuku Raut –

He speaks of the fear of life and death

The judgment of the Vedas

The hour of the Vedas

The rule of the Vedas

Fourteen verses and fourteen songs

The music never leaves the body

The body of music never leaves

I don’t leave it

It doesn’t leave me

Because I am my body and my body is me

It’s all far away, Yogi

The Yogi doesn’t know the Yoga –

the union that lies far away;

an endless search

You don’t know where it is

You haven’t found it yet

You besmirch the Master with your Yoga

(Once again, the glossary doesn’t contain the meanings of all the terms used here because the glossary is for the Chawrjya & DNoha Poems and the Wizard’s Ocean scripture, whereas this poem has been quoted in Bangla by Haraprasad Shastri only in the Mouthpiece to the entire book. The syntaxes, thus, often get tricky to comprehend. Ergo, much liberal translation in lieu of absolute honest transliteration. Readers may kindly excuse.)

Shantideva had also written a book of verses on the Thunder-Tantric Path of Buddhism that prevails in Tibet, as attested by the Bstan ‘Gyur section of the canonic literature of Tibetan Buddhism which contains, this book on Tantra by Shantideva – titled Shri-Gujhya-Samaj-Maha-Yoga-Tantra-Vali-Vidhi (literally: ‘the Secret Society Great Yoga of Tantric Rules of Rites, Rituals and Sacrifices’). This scripture mentions that Shantideva used to live in Jahor. We don’t know where Jahor is situated today.

However, that the Easy Path poet Raut Bhusuku whose songs find place in the Chawrjya collection had stayed in Bengal for long has been mentioned by the poet himself in a verse that begins with these verses:

‘baj naw paRee pNau-aa khaleyN bahiu/

aw-daw-yaw bangal desh luRiu//

aji bhusuku bangali voilee/

niyaw ghawriNee chanDalee leylee//

meaning,

You rowed the thunder-boat

along the canal of lotuses

and reached the country of Bengal – united

Today, Bhusuku, you become Bangali

You are wedded to the ChanDalee

Here United Bengal indicates the prevalence of advaita i.e. unitarianist Buddhism in Bengal. “Bhusuku, you become Bangali” implies that Bhusuku has taken to Unitarianism.

According to the Easy Vehicle (SahajYana), there are three paths –

1) that of the Avadhooti

2) that of the ChanDalee

3) that of the Dombee or the Bengalee

Now, in Vajrayana, the Avadhooti is one who holds the wisdom of Duality – Dwoito-Gyan/Dvaita Ynana, the ChanDalee is one who has both Dualistic (Dwoito/Dvaita) and Unitarian (Aw-dwoito/Advaita) wisdom as well as neither of those – both at the same time, whereas the Dombi or the Bangali is the holder of Unitarian Wisdom or Aw-dwoityo-Gyan/Advaita Jnana and is shorn of any form of Dualism in entirety. That Bengal was a place of Unitarian Wisdom or AdvaitaVaad in the 8th/9th/10th/11th Centuries AD and that Bhusuku had settled down in Bengal for at least for a while is evident from these verses.”

While interpreting this portion of the verse as quoted and explained by Haraprasad, a couple of caste-based and Tantric nuances ought to be kept in mind. In lay terms, ChanDalee means a lady from the ChanDal community – a historically repressed community, considered as an untouchable outcaste by the caste-system dominated Hindu orthodoxy, many members of which had sought refuge in Buddhism to get away from the casteist exploitation, Dombee implies a female member of the Dom community (the males being the Dombas) – another perceived untouchable and outcaste community, historically depressed, whose traditional job as assigned by the caste-based orthodoxy is to burn corpses in crematoriums and whose community-name indicates that the community was known to have been proficient drummers in ancient times and whose traditional deity is Dharma, represented at times by statues of King Yama of Vedic-Hindu mythology, at times by marks and anointments of vermillion on rocks and boulders, and at times as Dharmesh who resides in the Sari or Shaal (Shorea robusta) tree – all being indicators of subaltern pre-Aryan roots and Bangali implies a native resident of Bengal. In Tantric parlance, ChanDalee also implies inner body-heat – representative of, as Haraprasad says in the last paragraph as quoted above, Unitarianism in the Shunya-Tantric scheme of things.

Now, let us see what Haraprasad has to say about Bhusuku in yet another section of the 1916 publication – the one where he has attached short biographies of several Vajrayana bards who had written verses in the ‘Twilight’ language:

“Shantideva was a scholar and an author of Greater Vehicle texts such as ‘Bodhicharyavatar’. His biographer refers to him as Rautu which can mean, alternatively, perfume-trader, soldier, general, or shepherd, and also refers to him as Bhusuku. He had written his books sometimes between AD 648 and 816. Taranath says that he was born in Saurashtra. The name of his birthplace, however, cannot be read from the timeworn pages of his biography. However, it mentions that Shantideva stayed in the kingdom of Magadha, specifically at the Monastery of Nalanda, for long and that he had received his mystic instructions from Manjuvajra. From all these evidences, it seems like he had hailed from these eastern parts of the subcontinent.

Another Shantideva, who held the title Yogishawara, meaning, Yogi-God, had existed and had authored two books on Tantra – ‘Sri-Guhya-Samaj-Maha-Yoga-Tantravali-Vidhi’, meaning, Mister Secret Society Great Yoga Tantra Rules, and ‘Sahaj-Geeti’, meaning, Easy Songs. This Shantideva had a descendant named Mekley (Mekhla?) who had propagated a new path in Tantra and a book was written based on this new path. This book was called ‘Chitta-Chaitanya-Shaman-Upay’, meaning, Mind-Consciousness-Resistance/Death-Reaper-Way. According to information availed from the Bstan ‘Gyur scriptures his house was in ‘Jahor’.

Yet another Bhusuku was the author of Manuscript No. 4801 in possession of the Asiatic Society. This book contains instructions intended for Tantric Buddhist practitioners on ways and means of building a hut, and on sleeping, eating, drinking etc. This book contains some Bangla DNoha-verses as well.

It seems unlikely that our Rautu Bhusuku, poet of eight verses that appear in the Chawrjya collection, was the same person as the First Bhusuku or the Mahayana scholar Shantideva who seems to have belonged to times before the Bangla language had evolved even to its ancientmost proto form. Our Bhusuku belonged to later times – most certainly after that of Luipa – because Luipa was the initiator of the Siddhacharya sect that this Bhusukupa of the Charya songs belonged to. Both their times seem to be between AD 950 and 1050.

Tantric Shantideva had written a book called ‘Sahaj-Geeti’ of Easy Songs and the verses penned by the Bhusuku in the Chawrjyapawd collection were also about the Sahajiya or the Easy Path. Thus, these two might have been the same persons.

Now, was Bhusukupa, the poet of eight of the Chawrjya songs, the same person as the one who had written Manuscript No. 4801? They might have been, because the Chawrjya poems are in Bangla which is also the language of Manuscript 4801. However, in absence of further evidence, it would be incorrect to decide on this. That the Bhusukupa of the Chawrjya songs was Bengali is amply evident from some of the lines of his verses, especially the following:

‘aji Bhusuku BangaleeVailee

Ni-aw ghariNee ChaNDalee leylee’

(today, Bhusku, you become Bengali

you wed ChanDalee – the Untouchable Inner Heat)

His eight songs contain a total of three hundred and twenty three words other than the self-references. Of these, thirty seven are Sanskrit, sixty eight mutilated Sanskrit, one hundred and eighty six are in old Bangla and thirty two in prevalent Bangla.

Of the thirty seven Sanskrit words, ‘Samarasa’, ‘Sahajananda’ and ‘Virmananda’ are Buddhist terms, and most the remaining are still prevalent in Sanskrit. However, the word ‘uha’ is now used as ‘uhya’, meaning, unmentioned or hidden. Three other words – ‘khaw’, ‘kim’ or ‘king’ and ‘ma’ have fallen out of use.

The thirty two Bangla words are undoubtedly present in current usage of the language. The one hundred and eighty six words of ancient Bangla seems to have been in use during the times of Bhusukupa, when the language was new. Some of these ancient Bangla words are but alternative spellings of words still in use – examples of such being ‘ShaShahar’, meaning, moon, ‘Shahaj’, meaning, easy, ‘sasar’ that might mean the moon or might mean samsara, ‘ses’, meaning, end, etc. These might have been mistakes made by the scribe or it might be so that people in those days used to not make much ado about the ‘correct’ or ‘authentic’ spelling of words.

The genitive inflection is ‘r’ or ‘raw’ whereas the locative one is ‘ey’ or ‘eyN’ – both being complete Bangla usage. The locative-case exemplified through usages such as ‘hiaw-hNi’, meaning, in the heart, ‘tahiN’ (meaning – there) reflects a Magadhi style of usage. In the word ‘achchha-si’, meaning, to be, the ‘-si’ denotes second person singular number – a style of use that has also been found elsewhere in ancient Bangla literatures. The usage of the word ‘achchha-hu’, meaning, you be, through its ‘-hu’ reflects an use of imperative verb in ancient Bangla. The ‘-mi’ of ‘jan-mi’, meaning, ‘i know’, is an example of use of the first person – similar usages also being noted in other literary examples of the ancient Bangla language.

Because of all these reasons, we can clearly infer that the language used by Bhusuku was ancient Bangla”

One thing that becomes clear from the above text by Haraprasad is that there lies a distinct possibility of there being multiple Shantidevas and Bhusukupas among the several Buddhist monastic sects that had existed in Bengal during the Pala Empire (8th– 12th Century AD). There was also a certain Shantipa whose verse appears in the Chawrjya-geeti-kosh. However, this Shantipa was a different person. He was none other than Shanta-Rakkhit – a celebrated Vajrayana and Mahayana scholar from the 8th/9th century AD who was, as Haraprasad writes elsewhere in his biographical notes on the Twilit bards, ‘noted for his wisdom far and wide’, was also a gatekeeper of the monastic university at Nalanda, and is also often considered as a teacher to yet another great Mahayana-Vajrayana Bengali scholar from the 11th Century AD viz. Atish Dipankar.

(Shantarakkhit AD 725–788, painting from 19th CE)

As we can see, the names of many of these Vajrayana bards, including, but not limited to, the Eighty Four Siddhacharyas who are also venerated in the Nath Path of the mystic Himalayan Yogis, end with the syllable ‘pa’: eg: Bhusuku-pa, Saraha-pa, Dombi-pa, Shabr-pa, Dokra-pa, Kanho-pa, Lawa-pa, Mar-pa, Tilo-pa, Naro-pa, Milare-pa, Karma-pa etc. The ‘pa’ here draws from the Sanskrit term ‘Pawd-Acharya’, meaning, alternately, Poet-Scholar, or, Post-Holding-Scholar.

Quests for real faces hidden behind one thousand year old names are futile. Let us look at the magic instead, at the verses penned by Bhusukupa.

(Busuku, aka Bhusuku from the Sechen Archives)

- Verse No. 6 of the Chawrjya-Geeti-Kosh Collection

1.1. Verse in phonetic Roman Script

(Ra’aga PaTmanjari by Bhusukupa)

kahoiri ghini meli achchhahu kees/

beRil haak paRaw-aw choudees//

apoNa mangseyN horiNa boiree/

khawnaw naw chhaRaw-aw bhusuku awherii//

tin naw chhupawi horiNaa pinoi naw paaNee/

horiNa horiNir nilaw-aw Naw jaaNee//

horiNee bolaw-aw horiNaa suN hori-aa to/

ey bon chhaRee hohu vanto//

tawrawngaw-teyN horiNa-r khur naw deesaw

bhusuku vanoi mooRhha hiawhi Naw pawisawee//

1.2 Verse in Translation Based on Explanatory Notes by Munidatta/Meenanath/Luipa:

‘Hunters shout from all around the trap

The Deer of my mind hears them shout

He whimpers thus in fright:

“Whom do I take? Whom do I leave?

How do I live?”

The Deer – his flesh makes him the enemy

Bhusuku, Hunter – Guru’s wisdom be his arrows

Ever be he on the lurch

The Deer doesn’t eat grass

The Deer doesn’t drink water

The Deer doesn’t know where the Doe lives

But Hevajra, Lord of the Thunder –

Knows of Niratma, Woman of the Void Soul –

He knows where she is

The Doe, She is Her Void Soul

She loots the Cosmoplanet where they get drunk on matter,

on materials

and on subjects of subjugation

The Doe says to the Deer:

“hey listen, you,

leave the forest and reach my Void

you see, the body is a forest

Beyond which lies this forest of lotuses

there’s splendid happiness here

There are no lies here.”

The Deer hears the Doe

He must bolt with the Lightning now

And thus he makes his move

He runs through the forest sharp and fast

Until clouds and dust cover his hooves

Until the waves cover his hooves

And he isn’t here anymore:

For to the wilderness of lotuses has he run

To that wild happy forest has he run

Never shall he ever be seen again.’

Bhusuku – he croons:

‘the fools shall not get what this song says

either in their minds

or in their hearts

which are but the same

like everything is’

1.3 Verse in Roman IAST

kā.hair ghi.ni me.li ac.cha.hu kīs

be.ṭil hak paR.a cau.dīs

a.pa.ṇā māṅ.seṃ ha.ri.ṇā bai.rī

kha.ṇa.ha na chaR.a bhu.su.ku a.he.rī

ti.n na chu.pa.i ha.ri.ṇā pi.ba.i na pā.ṇī

ha.ri.ṇā ha.ri.ṇīr ni.la.a ṇa jā.ṇī

ha.ri.ṇī bol.a ha.ri.ṇā suṇ ha.ri. ā to

e van chā.Rī ho.hu vān.to

ta.raṅ.ga.teṃ ha.ri. ṇār khur na dīs.a

bhu.su.ku bha.ṇa.i mū.Rhā hi.a.hi ṇa pa.i.saī

1.4 Verse in Literal Translation

‘Whom do i leave? Whom do i take? How do i live?

The hunters are shouting from all sides!’

– (Thus spoke the Deer)

Own flesh makes the Deer enemy

Bhu.su.ku, the Hunter, leaves him not an instance

The Deer doesn’t touch grass, nor drinks water

The Deer doesn’t know where the Doe stays

The Doe speaks to the Deer – ‘Listen, Deer, you,

Leave the forest and go away’

The Deer runs fast – hooves fade to the waves

Bhu.su.ku says – ‘the fools shall not get this’

- Verse No. 21 of Chawrjya-Geeti-Kosh

2.1. Verse in phonetic Roman script

(Ra’aga BaraRhi by Bhusukupa)

Nisiaw andharee musa chaTara/

amia vakhayaw musa kawra-aw ahara//

mar rey joiaa musa pawaNa/

jeyN Naw tuTaw avaNa gavaNa//

bhava bindaraw musa khaNa-aw gatee/

chanchala musa kaliyaaN nashak thatee//

kal muSha uha Na vaNa/

gaw-aw-Ney uThhi chawrawaw awmaNa dhaNa//

taba sey muSHa unchala panchala/

sadguru bohey kariha so Nichchala//

jabeyN muSHaeyr achar tuTaw-aw/

bhusku vaNa-aw tabeyN bandhana fiTaw-aw//

2.2 Verse in Translation Based on Explanatory Notes by Munidatta/Meenanath/Luipa

‘The night is deep and dark

The rat scampers through

There’s wisdom in bodies

Thunder holds the joy of love

The rat licks honey

Honey be the nectar of realization

Moving through

the wheel of samsara

on and on –

never ceases

The jewel of mind never blooms

The mind is down

Evil winds blow

Halt the winds, Yogi

Kill the rat!

Your reckless movements

through the ever-turning wheel

shall then cease to be

Your body is the universe

The universe is your body

The rat is restless

The rat cuts through your body

The rat cuts through your universe

The rat cuts through the skies

The rat digs a hole for you

Yogi, know the restless rat

Yogi rey, kill the restless rat

Kill the rat!

Kill the rat!

Count its faults

and kill it!

before it sends you to hell down the hole!

You be the destroyer

Hold the stasis

And kill the rat

The rat is time

The rat has no colour

The rat has no race

When you hold your seat,

The rat destroys itself!

There’s a paddy field of autumn

in the sky

In that field, the mind,

is ever in zen

the rat reaches the Void sky

and scampers around in bliss

The rat wrecks the fields of zen

The rat eats the rice of autumn

The rat eats time

The rat is time

Time eats time

The rat destroys itself

Time destroys itself

Petrify the rat, Yogi,

Trap it with the wisdom-machine of SadGuru

Bhusuku says:

When the rat ceases to move,

Shackles of Samsara snap’

2.3 Verse in Roman IAST

ni.si.a an.dhā.rī mu.sā ca.ṭā.rā

a.mi.a bha.kha.a mu.sā ka.ra.a ā.hā.rā

mār re jo.i.ā mu.sā pa.va.ṇā

jeṃ ṇa tu.ṭa.a a.va.ṇā ga.va.ṇā

bha.va bin.dār.a mu.sā kha.ṇa.a gā.tī

cañ.ca.la mu.ṣā ka.li.āṃ nā.śak thā.tī

kāl mu.ṣā u.ha ṇa vāṇ

ga.a.ṇe u.ṭhi ca.ra.a a.maṇ dhāṇ

tab se mu.ṣā uñ.cal pāñ.cal

sad.gu.ru bo.he ka.ri.ha so ṇic.cal

jabeṃ mu.ṣā.er a.cār tu.ṭa.a

bhu.su.ku bha.ṇa.a ta.beṃ bān.dhan phi.ṭa.a

2.4 Verse in Literal Translation

Dark night, mouse moves

The mouse drinks ambrosia

Kill, O Yo.gī, the Rodently Breeze

That all coming and going break away

The mouse pierces the Universe, digs a hole

Know the Restless Mouse and be its Slayer

The mouse is Time the Destroyer – no colour can be felt

It rises in the skies to eat ā.maṇ-paddy – Mindless Zen

And yet, the Rat is Restless

In the Bo.dhi of Sad.gu.ru, make the Rat still

When the Rites of the Rat shatter,

Bhu.su.ku says, all ties shatter

………………………………….

2 ½ .Verse No. 23 (incomplete) of Chawrjya-Geeti-Kosh

2 ½ .1 Verse in phonetic Roman script

(Raga BaraRi by Bhusukupa)

jai tuhmvey vusuku aheyi jaibeyN mariha si panchajaNa/

nalNee-van paisantey hohisi ekumona//

jeevantey vela bihaNi mawelaw Naw-aw-Ni/

HoNu biNu mangsey vusuku padma-vana paisawhiNi//

mayajaal pasariu rey badheli maya-horiNee

sadguruboheyN bujhi rey kasu kahini//

2 1/2.2 Verse in Translation Based on Explanatory Notes by Munidatta/Meenanath/Luipa

‘Deer Hunter, if you want to go hunting,

Go kill those five deer

Who roam the forest –

Not the forest of lotuses, but the one before that

Dear Hunter, hunt those five down!

Hunt the senses down!

Kill the deer of reckoning!

Slay all that grow in mind!

Hunt consciousness!

Kill all stuff that’s here!

Bhusuku, Hunter

You are about to enter the forest of lotuses;

Focus,

Bring your mind together

Make it one

There’s great happiness in this forest

The day of wisdom dawns

The dark night dies out

(Hunter! Hunter! all of these happen in your lifetime!)

And now, as the day of wisdom dawns,

Hunter must enter the forest of lotuses

There’s great happiness in the forest

But first, Bhusuku the Hunter –

He must feast on the flesh of his hunt,

I must feast on the flesh of my hunt,

Bhusuku, Hunter,

enter not the forest of lotuses

without eating the flesh of your hunt

without gifting the flesh

of the dead

to the dead

The dark snake of shakti – she is to fade away

to happiness, utmost,

in the forest of lotuses

A doe named Maya –

She is the doe of heart

she spreads her net of magic

she enchants

You, too, have spread a net named Maya

Maya trapped in Maya –

You kill her Maya with yours

You kill her magic with yours

You slay the illusions

You aren’t enchanted anymore

Your vision is clear and blank

You have killed a doe named Maya

She is the doe of hearts bewitched

Sadguru – giver of great wisdom

His wisdom makes me get to know

Of tales such as this,

of whatever’s up with whom…’

2 1/2.3 Verse in Roman IAST

ja.i tuh.me bhu.su.ku a.he.i jā.i.beṃ mā.ri.ha si pañ.ca.ja.ṇā

na.la.ṇī.va.na pa.i.san.te ho.hi.si e.ku.ma.nā

jī.van.te bhe.lā bi.ha.ṇi ma.el ṇa.a.ṇi

haṇ bi.ṇu māṅ.se bhu.su.ku pad.ma.va.na pa.i.sa.hi.ṇi

mā.ā.jāl pa.sa.ri.u re bā.dhe.li mā ā.ha.ri.ṇī

sad.gu.ru.bo.heṃ bu.jhi re kā.su ka.hi.ni

2 1/2.4 Verse in Literal Translation

If you go hunting, Bhu.su.ku, kill Those Five

Focus as you enter the Lotus-Forest

The morning turns to life, the night dies

Bhu.su.ku wants meat; Bhu.su.ku won’t kill; he enters the Forest of Lotuses

He casts the Net of Mā.yā to catch the Doe of Mā.yā

The Wisdom of Sad.gu.ru makes me realise whose story this one is

{Three pages of the scripture being missing, four lines of the last song and the next two songs were not in the original manuscript as was found by Mmd. Haraprasad but was found in the Tibetan Buddhist Canon version of the text and its commentary. Subsequently, those were found & included by Probodh Chandra-Bagchi in Materials for a Critical Edition of the Old Bengali Charyapadas (A comparative study of the text and the Tibetan translation), Journal of the Department of Letters, Vol. XXX onwards, Calcutta University, 1938. The Open Knowledge Foundation Network, India Project has put translations of those in their online collection.}

……………………………………………………

- Verse No. 27 of Chawrjya-Geeti-Kosh

3.1 Verse in phonetic Roman script

(Ra’aga Kamod by Bhusukupa)

adharai var kamala bikasau/

batis yoini tasu anga uhlasiu//

chaliuaw ShaShahara magey avadhooi/

rawawNawhu Shahajey kahei//

chaliaw ShaShahar gau nivaNeyN/

kamalini kamala bahoi paNaleyN//

virmananda vilakshaNa sudh/

jo ethu bujhai so ethu budh//

vusuku vaNoi moi bujhhiaw meleyN/

sahajananda mahasuha leeleyN//

3.2: Verse in Translation Based on Explanatory Notes by Munidatta/Meenanath/Luipa

‘fourth night after full-moon

sunshine-thunder makes my lotus bloom

it bloomed at the half of night,

Thirty and Two Yoginis hoisted their bodies

in fulsome moonlight,

sweating Sweats of Delight

The jewel drives the moon;

The moon scales the peak

of Mount Thunder,

speaks of the Easy Path,

speaks of the jewel-crypt wisdoms,

and glides by to Nirvana

Soulless xylem flows through the stem

Soulless phloem flows through the stem

Thus the lotus be

Thus the body of the thunder be,

the thunder of the body be

Soulless be the goddess of nature

Soulless be Lady Lotus

Bodhichitta – Body of Thunder – be her man

They be flowing down the Strait of Love

the third state is pure –

Buddha knows it thus

King Yogi learns the path to reckoning

Bhusuku says –

Wisdom and the Ways unite

in me

and through this union

i feel

the joy of Easy Bliss –

that splendid, jubilant rapture’

3.3: Verse in Roman IAST

a.dha.rā.ti bhar ka.ma.la bi.ka.sa.u

ba.tis yo.i.ṇī ta.su aṅ.ga uh.la.si.u

cā.li.u.a ṣa.ṣa.ha.ra mā.ge a.va.dhū.i

ra.a.ṇa.hu ṣa.ha.je ka.he.i

cā.li.a ṣa.ṣa.ha.ra ga.u nī.vā.ṇeṃ

ka.ma.li.ni ka.ma.la ba.ha.i pa.ṇā.leṃ

vir.ma.nan.da vi.lak.ṣā.ṇ su.dh

jo e.thu bu.jha.i so e.thu budh

bhu.su.ku bha.ṇa.i ma.i bu.jhi.a me.leṃ

sa.ha.jā.nan.da ma.hā.su.ha lī.leṃ

3.4: Verse in Literal Translation

Lotus bloomed at midnight

Thirty and Two Yoginis danced their bodies up

The Moon driven along the Path of the A.va.dhū.tī

The Jewel speaks to the Easy

The Moon, driven, reaches Nir.vā.ṇā

The Lotus of Ka.ma.li.ni flows along the Canal

Vir.mā.nan.da, for certain, is Pure,

Those who realise thus are the Bud.dhas here

Bhu.su.ku says, i realise, through Union

Sa.ha.jā.nan.da – the Easy Bliss, in the Lī.la of Great Happiness

………………………………………………………

- Verse No. 30 of the Chawrjya-Geeti-Kosh

4.1 Verse in phonetic Roman script

(Ra’aga Malhari by Bhusukupa)

karuN meh nirantar fariaa/

bhavabhav dwangdwal daliaa//

uitta gaw-aw-N majhheyN advuaa/

pekhrey bhusuku sahaja sarooaa//

jasu sunantey tuTToi indiaal/

nihu rey ni-aw-mawN Naw dey ulas//

visaw-aw-vishuddhiN mai bujhh-jhhi-aw anandey/

gaw-aw-Naw-haw jin ujoli chandey//

ey toiloey eta viShara/

joi bhusuku feToi andhakara//

4.2 Verse in Translation Based on Explanatory Notes by Munidatta/Meenanath/Luipa

‘KaruNa Clouds bloom timeless

To end the fight between 0 and 1

Clouds rain mercy

On these brutal wars of otherness

Strange, in the aura-aurorae-soundwebbed sky,

Look, Bhusuku, true colours of ease arise!

The magic-web of senses –

hears this song

and tears itself apart;

Mind,

listless,

Giver of easy cheers –

goes to its sweet secret clime.

Bodhichitta goes to arcane lands

And makes everyone happy out there!

From pristine matter I learn, with joy,

How the moon shines the skies up

How easy joys wash all blindness away,

all delusion; –

This be the base of the three worlds

This be the fourth Path of Joy

This be the fond Moon of Love

Yogi Bhusuku rises

to tear darkness apart!’

4.3 Verse in Roman IAST

ka.ruṇ meh ni.ran.tar pha.ri.ā

bhā.vā.bhāv dwaṅ.dwal da.li.ā

uit.tā ga.aṇ mā.jheṃ ad.bhu.ā

pekh.re bhu.su.ku sa.ha.ja sa.rū.ā

jā.su sun.na.te tuṭ.ṭa.i in.di.āl

ni.hu re ni.a.maṇ ṇa de u.lās

bi.sa.a.bi.śud.dhiṃ ma.i bujh jhi.a ā.nan.de

ga.a.ṇa.ha jin u.jo.li cān.de

e tai.lo.e e.ta bi.ṣā.rā

jo.i bhu.su.ku hebh.bhai an.dha.kā.rā

4.4 Verse in Literal Translation

Clouds of Ka.ru.ṇā spread ceaseless

Slays the clashing Being and Not-Being

Risen, in the middle of the sky, strange

Behold, Bhu.su.ku, the own form of the Easy

Hearing that, the Net of Senses tear

Own mind in solitude, doesn’t cheer

Through the Purification of Subjects, i realised, in joy

Like the Moon shines in the Sky

This be the essence of the Three Worlds

Bhu.su.ku the Yogi tears darkness apart

……………………………………..

- Verse No. 41 of the Chawrjya-Geeti-Kosh

5.1 Verse in phonetic Roman script

(Ra’aga Kahngunjari by Bhusukupa)

ai-ey aNuawna ey jag rey vangtieyN so paRihai/

rajsap dekhi jo chamki-i sache king tang boRo khai//

akaR joiaa re ma kar hathaa lohna/

aisa sahabey jai jag bujhhShi tuTai baShNa tora//

maru-mareechi gandhabb-nairee dapatibimbu jaisa/

batabatteyN so diRh vaiaa apeyN pathar jaiSh//

bNadhisuaa jim keli karai khelai bahubih kheRa/

baluaateleyN sasarsingey akashey phulila//

rautu vanoi kaT bhusuku vanoi kaT saw-aw-la ais sahaw/

jai to mooRha achchhasi vantee puchchha tu sad-guru paw//

5.2 Verse in Translation Based on Explanatory Notes by Munidatta/Meenanath/Luipa

‘The wise know the world unborn

Kid Yogi, you see it born

you haven’t learned enough

You take the rope for King Cobra

Does it really bite you?

So don’t take the world as born

soil not your hands

your timeless wants shall break to bits

your endless burning shall cease to be

the world of the others shall pale away

So, don’t make your hands salty

Mirages in the desert –

Gandharv-Nagari – dreams –

— maya –

City of angels in the cloud

Pictures in the mirror

Water freezing to snow in atmosphere

Child of the childless playing in the shores,

playing her endless games,

swimming in the waves,

Sands that yield oil

The Rabbit in the Moon has horns

She rises with the moon

she rises to the peak of the moon

she makes the sky happy

and flowers bloom up in the sky

Bhusuku is a Shepherd

Bhusuku is a Cowboy

Bhusuku is a Prince

Bhusuku is a man of trade

Bhusuku is a man of war

Bhusuku is a man of peace

Strange Bhusuku speaks strange words:

“everything that exists – all matter,

all form – are like these!

such is their nature!

Ecstasy and surrender, the mind bewildered –

blinded by the pig’s poison

charmed by lights that fade,

by candles that cease to burn

If they cloud your mind, go to Sadguru

If delusions beguile, go to Sadguru

Sadguru holds the wisdom-torch”’

(alternate translation:)

They who possess the wisdom of Utmost Essence

will be knowing this

that the world is unborn

that it never was born

they will also be knowing this

that it’s a mistake to think that the world is true and honest

some people see a rope and mistake it for a King Cobra

But does the Cobra really bite them?

Truth rises when illusions fade

Strange it is, Kid Yogi!

But why soil your hands with salt and sand this?

It’s all an illusion

Beyond which lies the Shunya –

that unimaginable emptiness,

bereft of everything and nothing –

The truth of the world lies in this void

Know of this, Kid Yogi

And your desires shall fade

A mirage in the desert,

A city of angels,

A reflection in a mirror –

The world’s like these

The world’s a woman

She can’t have children

But she can make endless love

She can show endless magic

She knows endless tricks and games

She digs oil out of sand

She gives horns to rabbits

She blooms flowers in the sky

The Perfume Selling Prince says: ‘Strange it is!’

Philosopher Bhusuku says: ‘Strange it is!’

It’s all the same

It’s all nature

It’s all us and everything and nothing and the beyond!

Hey Fool,

Hey Doubter,

Hey Skeptic,

Go to the Sadguru to ease your mind,

to make your illusions dissolve in Emptiness

5.3 Verse in Roman IAST

ā.i.e a.ṇu.a.nā e jag re bhaṅ.ti.eṃ so pa.Ri.hā.i

rāj.sāp de.khi jo ca.ma.ki.i sā.che kiṅ taṅ bo.Ro khā.i

a.kaṭ jo.i.ā re mā kar hath loh.ṇā

ā.is sa.hā.be ja.i jag bujh.ṣi ṭu.ṭa.i vāṣ.ṇā to.rā

ma.ru.ma.rī.ci gan.dha(.bba) na.i.rī dā.pa.ti.bim.bu ja.i.sā

vā.tā.vat.teṃ so di.ḍh bha.i.ā a.peṃ pā.thar ja.iṣ

bāṃ.dhi.su.ā jim ke.li ka.ra.i ba.hu.bi.hā khe.Ra

bā.lu.ā.te.leṃ sa.sa.riṅ.ge ā.kā.śe phu.li.lā

rā.u.tu bha.na.i kaṭ bhu.su.ku bha.na.i kaṭ sa.a.lā a.i.sa sa.hā.v

ja.i to mū.ḍhā ac.cha.sī bhān.tī puc.cha tu sad gu.ru.pāv

5.4 Verse in Literal Translation

The world has been unborn since the beginning, it is manifest by mistake

One who mistakes the rope for a snake and startles – does ze really get bitten by a King Cobra?

Strange Yogi, O, make not your hands salty

If you realise the world in this being, your desires shall break away

Mirage in the Desert, City of Angels, Reflections in the Mirror

Water hardens to ice in the atmosphere

Child borne by childless woman – plays in such frolics O!

Like oil in the sand, like flowers in the sky made happy by the horns of the moon

The Prince says: Strange it is! The Perfume-Seller says: Strange it is! The Shepherd Says: Strange it is! The General Says: Strange it is! Bhu.su.ku says: Strange it is! – all beings have such Being

Fool, if you are still beguiled by errors, ask at the feet of Honest Guru!

………………………………………………………………..

- Verse No. 43 of the Chawrjya-Geeti-Kosh:

6.1 Verse in phonetic Roman script

(Raga Bangal by Bhusukupa)

sahaj mahataru fari-aw ey toilo-ey/

khasam sabhavey rey baNo muka ko-ey//

jim jaley paNiaa Taliaa veu naw ja-aw/

tim maN-raw-awNarey samarasey ga(g)an samaye//

jasu Nahi adhyaa tasu pareyla kahi/

aai anuanarey jam maraNa bhava nahi//

bhusuku vaNoi kaT rautu vaNoi kaT saw-aw-la eha sahav/

jai N aawayi rey N tNahi bhavabhav//

6.2 Verse in in Translation Based on Explanatory Notes by Munidatta/Meenanath/Luipa

‘The grand easy tree spreads

Across the three worlds

Thunder meets lotus

seed of ease is born!

And the seed of bliss is born!

Thus the tree

comes to be

It’s like the sky

The wise of the three worlds –

they come to know of its nature

they come to know of its bliss

they reach the ocean of freedom

Waves break

Water meets water

It’s all the same

jewel of mind keeps shining on

for Bodhichitta to shimmer in beauty

mind – at rest,

Wizards enter the sky

There’s no soul

There’s no self

There’re no others

Unborn, Deathless:

No moods to colour the mind,

No mind to colour the world,

No universe to be,

for King Yogi is free!

Shepherd Bhusuku

Cowboy Bhusuku

Warrior Bhusuku

Tradesman Bhusuku

Prince Bhusuku

Polite Bhusuku

Strange Bhusuku speaks

strange words

He says –

“such be the flow of life, death and beyond

such be its nature

Ahoy!

In this smooth, sober state

feeling the easy joys, the calm senses;

here,

there’s no being and unbeing

there’s no flow and there’s nothing to check the flow;

No Yogi arrives upon,

and no Yogi departs from –

this prison of cycles –

The Djinn-cage of life and samsara”’

6.3 Verse in Roman IAST

sa.ha.ja ma.hā.ta.ru pha.ri.a e tai.lo.e

kha.sa.ma sa.bhā.ve re bā.ṇat mu.kā ko.e

jim ja.le pā.ṇi.ā ṭa.li.ā bhe.u na jā.a

tim ma.ṇa ra.a.ṇā.re sa.ma.ra.se ga.a.ṇa sa.mā.a

jā.su ṇā.hi adh.yā tā.su pa.re.lā kā.hi

ā.i a.nu.a.nā.re jām ma.ra.ṇa bha.va nā.hi

bhu.su.ku bha.ṇa.i kaṭ rā.u.tu bha.ṇa.i kaṭ sa.e.lā e.ha sa.hāv

jā.i ṇa ā.va.yi re ṇa taṃ.hi bhā.vā.bhāv

6.4 Verse in Literal Translation

The Great Tree of Ease erupts in the Three Worlds

Being like the Void, who is free from the colours?

Like, when water falls on water, they become the same

Thus, the Jewel of the Mind enters the Sky in the Ra.sa of Sameness

They who have no sense of the Self – how do they feel the Other?

Unborn at the begininning – have no birth, death or being

Bhu.su.ku says: Strange it is! The Prince says: Strange it is! The Perfume-Seller says: Strange it is! The Shepherd Says: Strange it is! The General Says: Strange it is! – all have such Own Being

No arrival, no departure – there lies no Being and Unbeing

…………………………………………………………..

- Verse No. 49 of Chawrjya-Geeti-Kosh

7.1 Verse in phonetic Roman script

(Ra’aga Mallari by Bhusukupa)

vaaj Nav paRee pNauaa khaleyN bahiu/

adaw-aw bangaley klesh luRiyu//

aaji bhusuku bangalee vailee/

ni-aw ghariNee chanDalee leylee//

Dahi jo pancha paTaN ingdi bis-aa NawThha/

N janmi chiaw mor kahiN gai paiThha//

soN taw ru-aa mor kimpi N thakiu/

Ni-aw paribarey maha nehey thakiu//

choukoDi vanDar mor loiaa ses/

jeebantey maileyN nahi visheShh//

7.2 Verse in Translation Based on Explanatory Notes by Munidatta/Meenanath/Luipa

‘A making of love:

Boat of Thunder flows along

the Canal of Lotuses

I arrive on Undivided Bengal

United Bandits loot the Boat

Time for Bhusuku to roll in fatigue

Bhusuku is Bengali now

He rides the knowledge of unity

He weds ChanDalini, untouchable,

– the heat within –

They make love all day and all night

five shoulders burn

five seats burn

five planks burn

five fields burn

five foundations burn

Blue light burns

White light burns

Yellow light burns

Red light burns

Green light burns

All form burns

All feeling burns

All cognition burns

All volition burns

All consciousness burns

I have wasted all senses

I have wasted all matter

I shun all other ways

Don’t know where the mind enters

Don’t know where the jewel enters

There’s no gold

There’s no silver

There’s nothing on Planet Zero

There’s nothing on Planet Continuum

I live with my family

I live in great love

I reject all the others

I renounce all excesses

Forty million storerooms ravaged –

Bandit of Union robs them all –

Bengali of Union wastes them all –

Forty million rooms of reflection ransacked –

Forty million troves of judgment lie empty –

all treasures end in me

all treasures end with me

And now, there isn’t much to tell

between life and death

in my soul

And there isn’t much to tell

between the living and the dead

of my soul’

(alternate translation:)

You rowed the thunder-boat

along the canal of lotuses

and reached the country of Bengal – united

Today, Bhusuku, you become Bangali

You wed ChanDalee

The Garrison rested in Five Columns

You raze the Army down

You singe them with your Fire of Ecstasy Sublime!

Your material senses have thus been burnt

Your conscious has thus been charred

Now, I don’t know where my mind has reached

My Tree of Emptiness stands no more

It had lived in great joy in with its own family

It had looted my Forty Million Rooms of Treasure

Now, there isn’t much

between Life and Death

7.3 Verse in Roman IAST

vāj ṇāv pā.Rī paṃ.u.ā khā.leṃ vā.hi.u

a.da.a baṅ.gā.le de.ś lu.Ri.u

ā.ji bhu.su.ku baṅ.gā.lī va.i.lī

ni.a gha.ri.ṇī.re can.ḍā.lī le.lī

ḍa.hi jo pañ.ca pā.ṭaṇ iṅ.di vi.sa.ā ṇa.ṭhā

ṇa jā.na.mi ci.a mor ka.hiṃ ga.i pa.i.ṭhā

soṇ ta ru.ā mor kim.pi ṇa thā.ki.u

ṇi.a pa.ri.vā.re ma.hā ne.Re thā.ki.u

ca.u.ko.ḍi bhan.ḍār mor lo.i.ā ses

jī.van.te ma.i.leṃ nā.hi vi.śeṣ

7.4 Verse in Literal Translation

Thunder-Boat flows along Lotus-Canal – Man and Woman unite

In the Unitarian Country of Bengal – dacoits ransack

Today, Bhu.su.ku becomes Bengali

Own wife be Can.ḍā.lī – the Untouchable Heat Within

Five Seats burnt, Subjects of the Senses lain waste

Don’t know where the Jewel of my Mind enter

i have no gold or silver left

i stay within my family in Great Fondness

my Forty Million storerooms looted – they end with me

There isn’t much between the Living and the Dead

…………………………………………………….

Sources:

Several resources of wisdom were made use of to cull out stories on Bhusukupa and his verses. By and large, this can be considered as a composite work of translation, where a large section of the prose parts have been translated from the Bangla prose used by Haraprasad Shastri in the book Hajar Bawchhor Purano Bangala Bhasha-ey Bouddho Gaan o DNoha, Bongiyo Shahityo Porishawd, Bongiyo Shahityo Porishawd, 1916, whereas the verse parts from the Twilight Language verses as presented in modern Bangla script in the same book.

Several works of several scholars have come to use while pursuing on this journey in search of Bhuskupa. These include, inter alia, the works of the 16th-17th CE Lama Taranath especially his ‘Buddhism in India’, of Probodh Bagchi, especially his voluminous Materials for a Critical Edition of the Old Bengali Charyapadas (A comparative study of the text and the Tibetan translation) as published in several parts by the University of Calcutta between 1936 and 1940, of Taraprasanna Bhattacharya – a Sanskrit pundit employed by the Bongiyo Shahityo Porisahwd who had translated the Sanskrit annotations attached to the Chawrjyapawd verses into Bangla, of Vidhushekhar Shastri who, in 1927, had refuted Haraprasad’s contention on the independent existence of the Twilight Language, of Mircea Eliade, who, in 1971, had sought to affirm the stance of Vidhushekhar, despite acknowledging the secretive nature of the language, of Rahul Sankrityayan whose introduction to the 1957 publication of Sarahapa’s Dohakosh by Bihar Rashtrabhasha Parishad, had ‘stirred the pot’ in times of claims to literary inheritances of the Twilight Language, of the studies in Dakarnawb-Tantra undertaken by Nagendra Naryan Chaudhuri (1935) of several works by Dr. Shashibhushan Dasgupta including but not limited to Bouddho-dhawrmo o Chawrjya-Geeti (1964) and Obscure Religious Cults: As a Background of Bengali Literature (1946), of several works by academic luminaries such as Ed Dimcock, Giuseppe Tucci, Keith Dowman as well as those by contemporary scholars such as Roderick Bucknell and Marin Stuart Fox (1986) and Judith Simmer-Brown (2002) Miller, Vandome and McBrewste (2010) et al, who have all continued with research on the Twilight Language across the past few decades, of Geetika Kaw Kher (2014) to whose researches on Vajrayana iconography i owe the most cherished one among all the illustrations presented above, to Debaprasad Bandyopadhyay whose mind-bogging range in terms seeking the connections and linkages of Sahajiya deho-tattvic (meaning: related to the body-theory) philosophy to the Tantric Praxis of the Siddhacharyas and other bards who had written these earliest Twilight Language literatures.

Along with these names, several online portals, including, but not limited to, Banglapedia, the Buddhist Door, the Wisdom Library, the Chinese Buddhist Encyclopedia, the blog Luminous Emptiness run by Mark Carter, the illustrations uplinked at various times by the website www.himalayanart.org etc. have all provided me with the courage to swim in the endless ocean of Bhusukupa’s wisdom.

Atindriyo Chakraborty is a writer and poet

http://atindriyo.blogspot.in/

SIGN UP FOR COUNTERCURRENTS DAILY NEWS LETTER