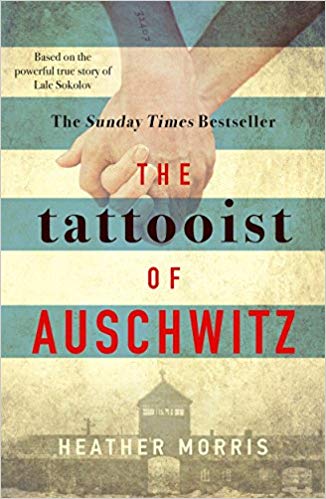

After reading this book “ The Tattooist of Auschwitz”, the first thought that came into my mind was that this novel based on the life of one man and his wife among others could be the fiction companion of Victor Frankl’s immortal work “ Man’s search for Meaning” written in similar circumstances in a concentration camp. But on deeper reflection, a different morally grey area came up. The main character in the book, the tattooist, originally a Jew from Slovakia Ludovit

Eisenberg, takes up the unenviable but coveted job of the tattooist, the guy who tattoos in the number by which every prisoner entering Auschwitz would henceforth be known. The job is a coveted one because it is connected to a section to the German administration that permitted several immunities and privileges. Ludovit ( Lale in the book) made full use of them for himself, his fellow prisoner Gita, who he would later marry and his friends by getting them access to food,

medicine, and clothing.

Many characters flit and out of the book, but one that gets limited attention is a girl called Cilka. Cilka is another girl along with Gita and her friends in the camp, but unlike all other prisoners, who have to shave their hair, Cilka is allowed to keep hers. Not too long after she enters the camp, she catches the eye of the camp commandant and is essentially forced to become her mistress. As the commandant’s mistress, she too has certain “privileges” and in fact once then Lale crosses the line and the boundary of his privileges and is pushed into a torture chamber, it is Cilka’s intervention with her lover that restores him his previous job and his privileges.

The moral question creeps on you slowly as it does on Lale. As the ” Tatowierer” – German for the Tattooist, he enjoyed certain freedom and liberties. The question and one which Lale lived with nearly all his life was this – was he just fighting to survive as all in the camp were in their way, or by embracing the job of tattooing numbers on peoples’ arms that would often decide their fate, obliterate their identities as people and even decide if someone would live or die. More than two years pass by before the Soviet Army liberates the camp and the anarchy and chaos descends. When the dust settles, Lale has found Gita and marries her, takes a Russian surname and sets up a prosperous business. That he would eventually fall foul of the Communist government and lose his business is another story but from the end of the war on, he and his wife live a generally comfortable life.

At the other end, the trials to try war criminals has begun. While Lale is building up his business and setting up home with his wife, Cilka is picked up as the Soviets overrun the camp and capture her. Putting her on trial as a Nazi collaborator, she is sentenced to ten years of prison in Siberia….. The question before Lale , the question before us is this …. Just who is a collaborator …. Someone who is abducted, reluctantly succumbs to repulsive advances night after night and pretends everything is fine as she settles in to work every morning or the privileged Tattoo who equally and even more telling, willingly took on a role that offered him a modicum of power, definitely a lot of immunity and privilege but was welcomed back into his homeland as a brave refugee as a brave and courageous man who had seen and endured it all…… What makes one person a collaborator and another a brave survivor? Gender, subjectivity, karma or simply the roll of the dice.

Shantanu Dutta, a former Air Force doctor, has been associated with the nonprofit sector for the last 25 years and more..

SIGN UP FOR COUNTERCURRENTS DAILY NEWS LETTER