COP 25: Hiring a thief to guard one’s home

The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) concluded its 25th Conference of Parties (COP 25) meeting in Madrid on 14 November 2019, where it discussed how to tackle the growing climate crisis. After nearly a fortnight’s deliberations by representatives of nearly 200 nations, COP 25 closed without a satisfactory conclusion, which made the United Nations General Secretary, Antonio Gutteras term COP 25 as a “lost opportunity.” Others have dubbed it as Flop 25 as it added no strength to the already weak 2015 Paris Agreement.

The governments of about 200 countries spent most of the COP 25 time haggling over two issues that are for most part peripheral to reducing emissions. The first was carbon market mechanisms by which countries can trade in carbon credits. A similar mechanism that was in place under the Kyoto Protocol, the precursor climate agreement to the Paris Agreement, had not helped in reducing emissions. The second was financial assistance to nations more vulnerable to climate change impacts, where the developed countries balked from taking legal liability for their historic emissions that are responsible for the impacts. On both issues there was no agreement and they were put off for discussion to COP 26, an important meeting to happen in 2020 where additional measures that are needed to bend the greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions curve further will be discussed. This is necessary for global warming to remain within the 1.5-2oC ‘red line’ by 2100, instead of the 3-4oC that it is forecast to reach with the current mitigation measures in place.

COP 25 very visibly ignored what science is telling the world regarding what may happen in future if we continued along the current course in favour of economic growth. COP 25’s undue emphasis on carbon trading and loss and damage financing makes it appear that commerce is the central driver that can stop global warming, and not science. This is akin to hiring a thief to guard one’s home. Commerce, particularly in the era of globalization, has played a major role in expanding global consumption of fossil fuels.

For there to be a fighting chance of halting global warming, the discourse must be changed to again make science central to the problem of tackling climate change.

Observed climate change impacts

The World Meteorological Organization (WMO) recently released a document titled, WMO Provisional Statement on the State of the Global Climate in 2019 (WMO2019), which gives us the latest picture of state of the global climate. The main findings are summarized below:

Atmospheric GHG concentrations rise unabated: Global atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gases reached record levels in 2018 with carbon dioxide (CO2) reaching 407.8±0.1 parts per million, or 147% of pre-industrial levels.

Temperature rise: Global mean temperature for January to October 2019 was 1.1±0.1°C above pre-industrial levels. Since the 1980s, each successive decade has been warmer than any preceding decade since 1850.

Ice melt: The daily Arctic ice extent minimum in September 2019 was the second lowest in the satellite record. In 2019, Antarctica saw record low ice in some months.

Sea rise: Between 1900-2010, the global mean sea level rose by 0.19 m, about half of which happened in just the last 27 years. The average sea level now rises at 3.25 mm/year.

Extreme weather events: Europe experienced record temperatures in 2019 summer. Vérargues in Southern France set a national record by hitting 46oC on 28 June 2019. The United States Midwest experienced a cold spell through most of 2019, with Mount Carrol in Illinois state recording a temperature of -38.9oC on 31 January 2019. Rainfall in India in 2019 was 10% above the 1961-2010 average, with about 1,000 lives lost in flood episodes.

Storms and floods: Between January and June 2019, 7 million people were displaced by hydro-meteorological events, including cyclones Idai in southeast Africa, Fani in South Asia, Dorian in the Caribbean, and flooding in Iran, Philippines and Ethiopia. Two million people were evacuated in Bangladesh to avoid Cyclone Bulbul that hit Bangladesh and eastern India in November 2019.

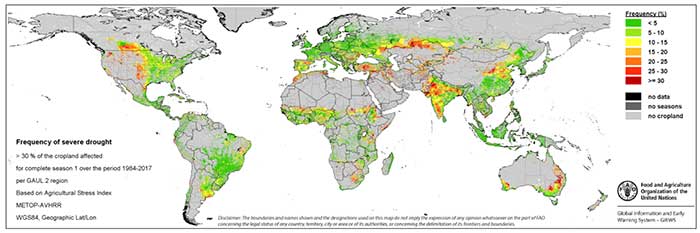

Drought: The Mekong Basin, the Laos-China border and parts of Australia experienced drought in 2019. Drought conditions also prevailed in the Horn of Africa and in Central America in the first half of 2019, leading to shipping restrictions in the Panama Canal.

Frequency of severe drought in cereal areas, 1984-2017 computed using remote sensing data (Source: FAO)

Health effects: In France, 1,462 excess deaths that occurred this summer are attributed to heat waves. About 3 million temperature rise-related dengue cases, including around 1,250 deaths, were reported from the Americas in 2019.

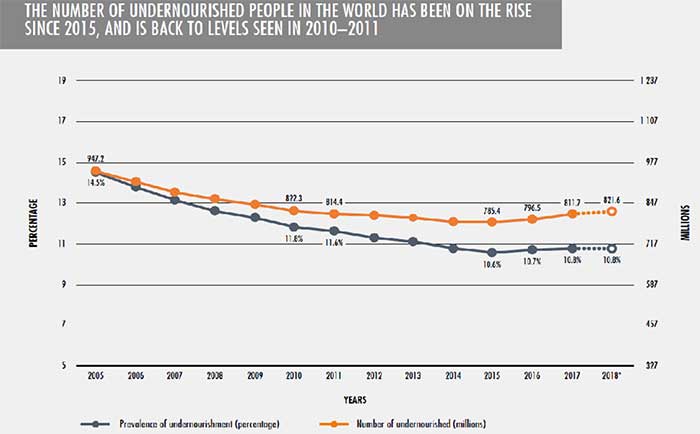

Food security: Between 2006-16, developing countries lost about 26% of their agricultural produce to climate-related disasters, in which floods caused two thirds of the crop losses, and droughts caused 90% of the loss of livestock. After a decade of decline, hunger is rising again – over 820 million people in the world suffered from hunger in 2018. The situation is most acute in sub-Saharan Africa. Drought has increased food insecurity in many African countries—Ethiopia, Somalia, Namibia, Kenya, Uganda. Floods have done the same thing in Malawi, Mozambique, and Zimbabwe.

Under-nourishment on the rise since 2015 (Source: WMO)

Vulnerability of displaced populations: Kutupalong in Bangladesh, where nearly one million Rohingya refugees from Myanmar were resettled, was hit by floods, landslides and wind storms in 2019. An intense drought in 2018 followed by flash floods in Afghanistan in April 2019 displaced over 30,000 persons in Herat.

Demand side management aided growth of fossil fuels

Fossil fuels are central to development as well as to the climate crisis. They dominate the energy scene, accounting for 81% of global energy use. Seventy six percent of GHG emissions and 90% of CO2 emissions are due to the use of fossil fuels. The Emissions Gap Report 2019 (EGR2019) states that to remain within a temperature rise of 1.5oC, GHG emissions that were 55.3 GtCO2 (with LUC) in 2018 must drop to 25 GtCO2 by 2030 at a steep negative growth rate of 7.6% per annum.

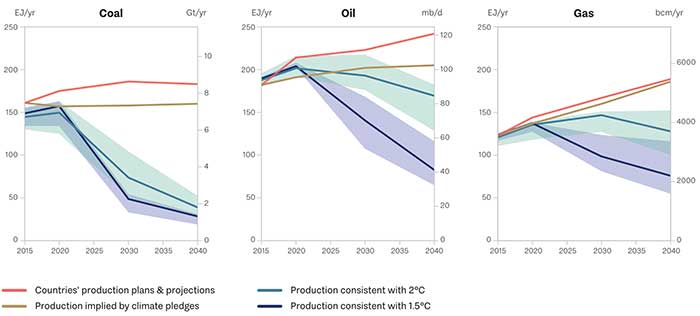

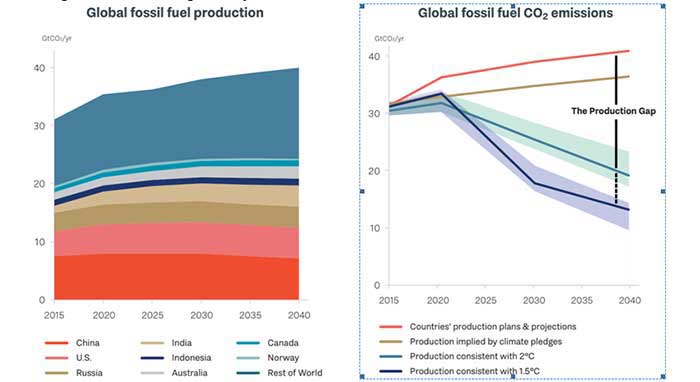

The 2019 Production Gap Report (PGR19), published by UNEP and five other organizations analyses the discrepancy between countries’ planned fossil fuel production and global production levels consistent with limiting warming to 1.5-2°C.

Much of the current global thinking regarding fossil fuel reduction has been on demand side management by increasing energy efficiency, making renewable energy cheaper than fossil fuel energy, and through market mechanisms. The former two processes kicked in the Jevons Paradox, and as they made more energy available, consumption increased, e.g., as renewable energy became increasingly available at cheaper rates, it complimented fossil fuels rather than replace it.

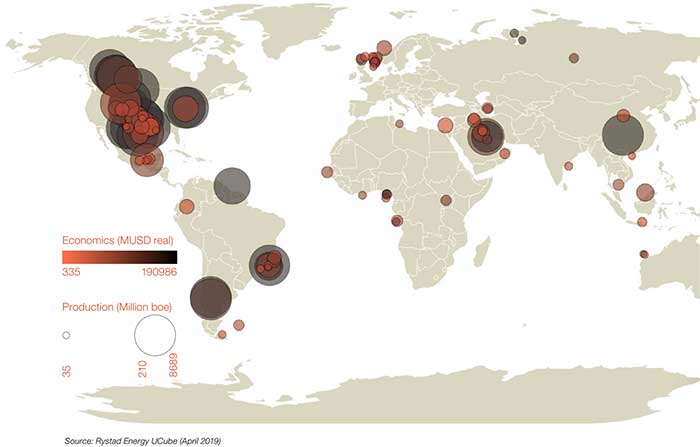

Consequently, the fossil fuel industry is poised to make an investment of US$ 1.4 trillion in new oil and gas fields between 2020-2024; and this excludes pipelines, export terminals and other infrastructure.

Top 100 New Oil and Gas Projects (Shale and Conventional), by Projected Production, 2019-2025

Coal production in 2030 is projected to be 280% more than what it should be to be consistent with a 1.5°C pathway. Corresponding figures for oil and gas are 59% and 70%, respectively in excess of what they should be to be in line with a 1.5oC temperature rise.

Expected coal, oil and gas production (EJ/yr) 2015-2040 (Source: PGR19)

By 2030, fossil fuel use is expected to cause emissions that will be 39 GtCO2 (120%) in excess of what they should be to keep within a 1.5oC pathway.

Emissions from fossil fuel production and production gap to remain within a 1.5-2oC pathway (Source: PGR19)

Every major petroleum company, including BP, Shell, Total, Equinor, has sanctioned new oil and gas projects that are not Paris Agreement compliant. Just 25 petroleum companies are responsible for 50% of the production from new investments made in the next 5 years.

Economic clout gives these companies enormous influence on governments. It is small wonder then that COP 25 negotiators, influenced by petroleum companies, choose to haggle over the mechanics of demand side management that have a proven track record of failing. The COP 25 negotiations are summed up neatly by Francis Stuart from the Scottish Trade Union Congress who said that “They are much more interested in trading emissions and making money from it than actually reducing them.”

Supply side management

Had COP 25 seriously considered what science is telling us about climate change impacts as, for example, it did in the WMO2019 report and the Emissions Gap Report 2019[2] (EGR2019), and listened to people’s voices, the meeting may have been more productive.

Science has provided strong evidence that the impacts of climate change are now clearly visible, that current effort to halt it is weak and therefore warming by 2100 will be in the range of 3-4oC. A statement titled “World Scientists’ Warning of a Climate Emergency” signed by 11,262 scientists from all over the world, reminds us of the deep environmental crisis we are in today and urges us to “leave remaining stocks of fossil fuels in the ground,” i.e., a supply side management measure.

Over 5 lakh activists marched through the streets of Madrid in the 2nd week of December 2019 shouting similar slogans. From within the babble of their voices came important messages such as “Keep the climate, change the economy,” and “There is no Planet B.” These slogans are asking for supply side management measures that ask for forsaking profits in favour of protecting the climate by keep the remaining fossil fuels reserves in the ground and consequently crimping fossil fuel availability. Several climate scientists also gathered in Madrid to communicate their findings and to warn the world that we must act decisively and urgently to curb fossil fuel use. Yet, COP 25 preferred to procrastinate, and help petroleum companies rather than listen to science and people’s voice.

Uniform emissions reduction rate for all nations is not climate justice

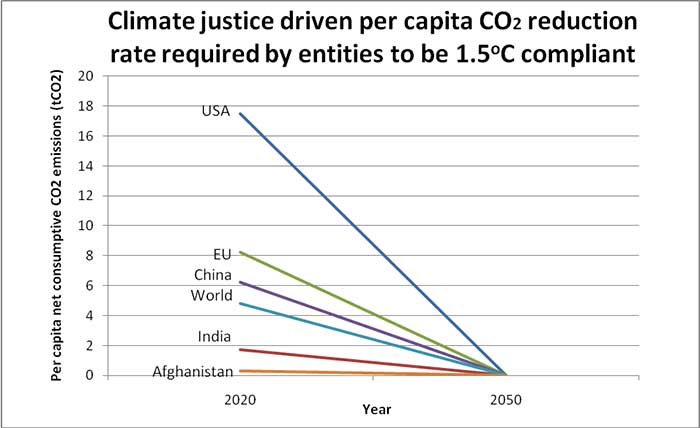

To contain warming to less than 1.5oC, the EGR2019 states that global emissions must reduce by 7.6% per annum for the next decade. Would it serve the principle of climate justice if this emissions reduction rate were applied uniformly to all countries? Should Afghanistan with a per capita emission of 0.31 tCO2 per annum reduce at the same rate as the USA that has a per capita CO2 emission of 17.5 tCO2?

The North nations accelerated their GHG use between the 18th and 20th Centuries, giving them a head start to “develop” their countries. South nations started accelerating their GHG emissions only in the last 3 decades, leaving their development handicapped. The per capita historic emissions of North and South nations are 1,200 and 85 t/person[3], respectively. With no viable alternative energy source that is a replacement to fossil fuels in sight, asking South nations to cut their emissions by 7.6% per annum by reducing their fossil fuel dependence by roughly the same amount tantamount to sentencing them to remaining permanently under-developed in comparison to North nations.

Moreover, South nations are more vulnerable to climate change, e.g., South Asia is one of the two most vulnerable regions to climate impacts, particularly its vulnerable populations such as indigenous people, fisher folk, etc. India will be subject to internal stresses such as extreme weather events, sea rise, floods, droughts, decreasing food and water security, and internal migration. It will also be subject to external stresses as almost all of the Maldives and a quarter of Bangladesh will be under the sea by 2100. Nepal and Bhutan will reel under frequent glacial lake outburst floods and consequent devastating flooding. Pakistan and Afghanistan will become severely water stressed countries as their rivers are highly dependent on glacial melt, and as glaciers melt, their rivers will run dry.

One way to increase the resilience of South Asian populations to climate impacts is through economic development. The choice of fuel to do this requires debate. The efficacy of using renewable energy for raising development standards of the most vulnerable populations in South Asia is yet to be established. Yet, if fossil fuels were used to do this, how much of them are required? And would this quantity of fossil fuels add significantly to warming?

A way out of this conundrum is to apply the principle of Common but Differentiated Responsibility, formalized in the 1992 Earth Summit. This adds climate justice to the emissions reduction recommendation of EGR2019 as it allows South nations to have lower emission reduction rates than North nations. South nations can then use the more readily available fossil fuel energy to increase the climate resilience for their vulnerable populations.

How should the remaining 1.5oC compliant emissions be divided between North and South nations? If equal per capita emissions are given to all persons in the world for the next 10 years, each person gets 20.75 tCO2. An average American with current per capita emission of 17.5 tCO2 would use up 85% of this amount in 2021 and would have next to nothing left in the subsequent 9 years, i.e., the emission reduction would be drastic. Whereas, an average Indian would use only 1.8 tCO2 in 2021, and would have almost 19 tCO2 for the remaining 9 years, i.e., there is even room for a little growth in per capita emission rates.

There are other ways of doing this division. If historic emissions are used as the basis of equity, emissions reduction rate will be so steep for North nations that their curve will fall off the chart, but it will be much gentler for South nations. If South nations were generous to North nations and agree that each person from a North nation is permitted 1.5-2 times their per capita emissions, the emission reduction rate would be less steep for North nations though greater than 7.6%, and that of South nations would be less than 7.6%.

That climate justice must be made central to the emissions reduction discourse has been stated by others earlier. For example, Our Future Uncompromised, a website that discusses sustainable development, computes 1.5oC compliant emissions reduction at -38% pa for very highly developed countries (US is -55% pa), -24% pa for EU, -22% pa for China, and -6% for medium developed countries such as India.

Whatever be the emission reduction rates, the graph of any method that incorporates climate justice with emission reduction will look something like figure below. The slopes of North and South nation curves will change with the assumptions made, but the slopes of North and South nations will be respectively above and below the EGR2019 mean of 7.6% pa emissions reduction for the world as a whole.

Source: Author’s contribution

Given past experience, it is highly unlikely that there would be agreement between North and South nations on emission reduction rates. They will hotly debate methodologies and outcomes of various computations till the cows come home, and probably never come to an agreement, as they will place national interest before global interest. And even if an agreement were hammered out, how would it be implemented, and monitored for compliance? Our Future Uncompromised suggests that emission reduction percentages must have legal sanction. While that is required, climate agreements have moved in the opposite direction. The Kyoto protocol was binding while the Paris Agreement is non-binding on the parties that signed them.

Only the world’s people can untie these intractable Gordian knots. It is in their interest to curb emissions, hence it is they who can force a shift from demand side to supply side management to curb emissions, ensure climate justice and see that a climate agreement has legal sanctions. If this is not done, it bodes destruction for the environment and human society as we know them. Early results from the latest climate models predict that warming by 2100 may exceed 7oC.

We have a full blown climate crisis. Emissions reduction pathways and climate justice issues must now be debated by public and be made central issues in the all important 2020 COP 26 agenda, when the progress of Paris Agreement will be assessed, and attempts to raise ambition levels to restrict warming to 1.5oC will be made. These issues are far too important to be left for governments to decide.

Published in: Firstpost, 22 Dec 2019, https://www.firstpost.com/tech/science/cop25-gets-it-upside-down-climate-crisis-calls-for-justice-management-of-the-supply-side-7812111.html

Sagar Dhara is an environmental engineer with a specialization in risk analysis. He was earlier a consultant to UNEP, Director, Envirotech Consultants and a faculty at BITS Pillani

[2]see Climate crisis: Is there a Savitri to Save the World from Climate Catastrophe? in Firstpost for an analysis of the growing emissions gap

[3]Per capita historic emissions are computed by dividing the historic emissions (1751-2017) of a country/region divided by the current population

SIGN UP FOR COUNTERCURRENTS DAILY NEWS LETTER