Flunked out of the shramik special, dignity of labour wails! It breathed its last when a toddler tugged at the corpse of his (or her) dead mother at the railway platform. It died when a 20 something was found dead not before four days, in the toilet of a shramik special. It has died a thousand deaths ever since the not so special trains have been put on tracks to ferry the migrant workers stranded in different parts of the country.

Informal labour and COVID-19 Scenario in South Asia

Dignity of labour is enshrined in the Constitution of India. Fundamental rights are guaranteed by the Constitution to all people without any discrimination. The provision of fundamental rights preserve and protects the human dignity. As Chairman of the Drafting Committee of the Constitution of India, Dr BR Ambedkar was aware of the importance of human dignity and therefore incorporated it in the Preamble to the Constitution of India. Every person has inalienable dignity, duties and rights. Dignity has acritical relationship with class, caste, gender, race and religion. But the very idea of dignity seems to have been compromised severely in case of the migrants who got stranded because of the lockdown induced in the wake of covid-19 now renamed as SARS COV-2.

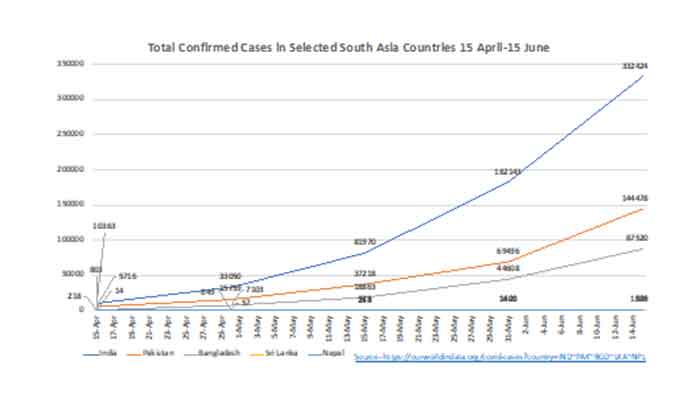

These migrants overwhelmingly comprise of workers in the informal sector. Close to 81% of all employed persons in India work in the informal sector. Among the five South Asian countries, informalization of labour is the highest in India and Nepal (90.7%), with Bangladesh (48.9%), Sri Lanka (60.6%) and Pakistan (77.6%) doing much better on this front. In fact, formal employment in Bangladesh is the highest in the region at 13.5%, but it also has high household employment at 26.7%, as per the International Labour Organisation. But the COVID-19 scenario in these countries reflects that the most informalized India is most infected too. While India has high informalization as well as highest number of COVID-19 cases in the region, Bangladesh has less than 50% informalization and the number of confirmed cases are also lesser, roughly one fourth of that in India, and more than half of that in Pakistan. It is noteworthy that the linear growth in the number of confirmed cases started to shift to exponential around the same time – last week of March and first week of April, in all the selected countries in the region. This is also the time when the lockdown was imposed in India. (Fig 1).

Fig 1

While Nepal had lowest infection, daily tests conducted per 1000 population was higher than India in April and May. Testing increased consistently across the countries during 15 April to 15 June. Pakistan with much lower infection and mortality than India, was testing more than all other countries selected for this analysis as on the last count. Number of confirmed cases as well as deaths, however, remained highest in India throughout this period despite similarity in proportion of population tested (Table 1).

Table 1-Daily Tests per 1000 Population in Selected South Asian Countries

| Date | India | Pakistan | Bangladesh | Sri Lanka | Nepal |

| 15-Apr | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0 | 0.02 |

| 30-Apr | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0 | 0.01 |

| 15-May | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0 | 0.04 |

| 31-May | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0 | 0.1 |

| 15-Jun | 0.1 | 0.12 | 0.09 | 0 | 0 |

Source- www.ourworldindata.org

Deaths due to COVID-19 need to be understood as direct and indirect. The direct death are those caused due to infection. The total number of reported direct deaths in India stand at 9520 as of 15 June 2020. The figures for Pakistan is second highest (2729) followed by Bangladesh (1171). Sri Lanka and Nepal reported much less deaths, 19 and 11 respectively. It is noteworthy that the increase in reported deaths during the first lockdown in India was about ten times from 32 on 31 March to 377 in 15 April. During the same period, Pakistan and Bangladesh recorded about nine times increase in the number of deaths, while Sri Lanka reported seven times increase. Between 31 May and 15 June, all the selected countries reported an increase of less than two times in the number of deaths Table 2). The indirect deaths are those caused due to the lockdown, propagated as the major measure taken to contain the health crisis.

Table 2 Total Reported Deaths due to COVID-19 in Selected South Asian Countries

| Date | India | Pakistan | Bangladesh | Sri Lanka | Nepal |

| 15-Mar | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 31 Mar | 32 | 18 | 05 | 01 | 0 |

| 15 Apr | 377 | 107 | 46 | 07 | 0 |

| 30-Apr | 1074 | 346 | 163 | 07 | 0 |

| 15-May | 2649 | 803 | 283 | 09 | 0 |

| 31-May | 5164 | 1483 | 610 | 10 | 06 |

| 15-Jun | 9520 | 2729 | 1171 | 19 | 11 |

Source- www.ourworldindata.org

According to data compiled by the SaveLIFE Foundation, a road safety NGO, there were at least 1,461 accidents during the nationwide lockdown from March 25 to May 31. At least 750 people were killed, including 198 migrant workers. There were 1,390 who got injured. Out of the total deaths which have occurred during the COVID-19 induced lockdown, 26.4% are those who died in their efforts to reach home and 5.3% were essential service providers. The overall deaths involving other road users was 68.3 percent.

It becomes imperative to examine why the migrant workers had to undergo this ordeal.

Lockdown and Travel Home

There seems to be little thought given to the decision of lockdown. Which was initiated with a fairly dramatized version of ‘junta curfew’- paradox of its kind. Why must people impose curfew on themselves? All the more when the reason to do so was ambiguous. More than rational, emotional conversation became the logic for decision making. The lockdown quickly followed the junta curfew without giving much time to think, collate and act. The educational institutions closed in haste, so did the offices and industries. The workers in these institutions were asked to work from home using the online platforms. The schools, colleges and universities were soon found to be adjusting to online learning (and teaching); those with resources adjusted to online mode, but the ones who were in the informal employment, had no time to adhere to the suggested ‘opportunity of spending time with family’. For them, joblessness followed by homelessness was the problem to deal with rather than the recommended ‘opportunity’. As their savings depleted, their conditions and hopelessness increased with each subsequent announcement of the extension of the lockdown. More than forty days went by before the state could respond to the needs of the migrants, who, let’s remember, are not a homogenous group. They are employed in both formal and informal sector at various levels of occupational hierarchy. They are international and internal migrants desperate to reach their homes in the wake of the closure induced by COVID-19.

The government launched the ‘Vande Bharat Mission’ on May 7 to evacuate Indians stranded in various countries due to coronavirus related restrictions. Under the Phase I of the Mission, the government evacuated 12,000 Indians from the Gulf countries, and remaining from the US, the UK, the Philippines, Bangladesh, Malaysia and the Maldives totaling to around 15,000 people from more than 12 countries in 64 flights. In Phase II which began on May 16 and is to end on 13 June, around 32,000 Indians from 21 countries were brought back between 16-22 May. India included private airlines in the second phase of the “Vande Bharat” mission. Of the 45,000 Indians who have returned by the end of May, 8,069 are migrant workers, 7,656 are students and 5,107 are professionals. During the two phases 429 Air India flights from 60 countries are scheduled to land in India. About 5,000 Indians have returned through land border immigration checkpoints from Nepal and Bangladesh. Efforts are also being made to assist return of stranded Indians from Latin America and Caribbean, Africa, and parts of Europe through the foreign carriers flying to India primarily for evacuation of their nationals. About 300 stranded Indians from Peru, Mexico, Belize, Guatemala, Honduras, Portugal and Netherlands have been brought in. Additional 18 countries in the second phase include Indonesia, Thailand, Australia, Italy, France, Germany, Ireland, Canada, Japan, Nigeria, Kazakhstan, Ukraine, Kyrgyzstan, Belarus, Georgia, Tajikistan and Armenia.

The government extended all possible support to bring back the Indians who chose to leave the country for personal benefits- employment, profession and education. The same government took more than forty days to articulate a simple measure to enable travel for the migrant workers who offered their toil to the country to build it- from the precincts of corporate world to the highways and flyovers and high rise buildings.

Less than ordinary Shramik Special

The railway ministry announced 800 Shramik Special trains from 1 May, ferrying home 10 lakh migrant workers who were stranded in various parts of the country due to the coronavirus-triggered lockdown. Uttar Pradesh received the maximum number of trains followed by Bihar. Gujarat has remained the top originating state, followed by Kerala. From 11 May, these Shramik Special trains increased the number of passengers to 1,700 from the earlier 1,200. Initially these trains had no stoppages. But the railways announced on 11 May up to three stoppages in the destination states. The cost incurred on these special train is around Rs 80 lakh per service. The Centre had earlier stated that the cost of the services will be shared on a 85:15 ratio between Centre and states. It was also stated that the trains will make the trip only if they have a 90-per cent occupancy. Subsequently, the Union Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) said the Railways will run 100 Shramik Special trains every day to facilitate faster movement of stranded workers. As the Indian Railways continues to operate ‘Shramik Special’ trains, civil society organisations have been drawing attention towards the process of acquiring tickets, permission etc for travel which lacked standardization causing stress and anxiety among the aspirant travellers. The special train services can be available on registration of migrant workers for traveling back to their homes. Similar to those stranded aboard. But in case of the migrant workers stranded in our cities here, the process is cumbersome and unfriendly. It has been left to every district to devise its own system, despite railways being a subject of the ‘Union List’. The workers are unable to fill online forms as most of them have low levels od education and are disgusted and tired of running from one office to the other for what they could have done just by buying a ticket and sitting in the train, in ‘normal’ times; and if instead of ‘special trains’ regular trains continued to ply but with restricted capacities of may be one-third. The process has also become a source of extracting money from the already miserable workers. A nineteen year old decided to walk back from Gandhinagar in Gujarat to Balrampur in Uttar Pradesh. The appalling state is evident from the following narrative of this young migrant worker.-

“It is up to God if we can reach our destination. We tried the process of online booking for availing seats several times. We approached multiple people. We went to Sabarmati station. We sought assistance from the police. Different police booths gave different information. Eventually, nobody could help us out. My parents are waiting for me at home. I am going for them”.

A pertinent question here is that why were the special trains started? We already have one of the densest network of rails. Why could not the same be used, albeit with lower occupancy- while plying on existing lines and stoppages. Then the trains would not have ‘lost their way’ on the tracks and reached places other than the destination. This is like a similar quiz to why the ‘PM Cares’ was established when there already exist the PM Relief Fund. This question will continue to haunt precisely because of the long delays, death and disease encountered by the travelers in these train. Shortage of water, food, unclean toilets and zero adherence to disease distancing and sanitization. Why did we at all have ‘special’ trains in which everything was poorer than the ordinary…? For the sake of name? another feather in the cap? Yes, but this feather has withered and the cap is in tatters. A stitch in time seems to be a distant dream to save nine any more.

Current Scenario

The country has registered increase in national recovery rate to 48.2 percent with 4611 positive cases having cure in last 24 hours on 7 June. This rate has doubled from 24.5 percent on April 29. The spread, however, continues unabated as the Unlock version 1.0 rolls out from 8 June, with COVID-19 figures standing at 246,472 confirmed cases, and 6873 deaths. India took only about fifteen days to double from 100,000 to 200,000 positive cases. It is paradoxical to note that India announced the lockdown on 25 March when the number of confirmed cases was 657, extended it further on 15 May when the confirmed case were more than 8000. Now when we rank fourth in the world, with nearly three million cases, we seemingly have no option but to unlock- after the devastation set in by the series of lockdowns. The migrant workers were kept in spaces and conditions not conducive to living while in their cities of adoption, and had to travel in haste, unprepared and even surreptitiously, hungry and unsafe perforce. They are being stigmatized for having carried the infection to the rural areas- their places of origin and poor health infrastructure. The inadequate and ill-equipped quarantine centres, will be closed by mid-June in most state, and given the poor health infrastructure in the rural areas, In the name of addressing the issue, states are doing away with welfare oriented labour laws. They are passing stricture to the tune that employers will have to seek their permission to employ them or they cannot leave the state as the lockdown is opening and the industry needs the workers! Distress induced returning back to villages in the times of COVID-19, is perhaps for the first time in the history of migration, in the reverse direction. Can there be a better deal for these people who wish to exercise their choice of place to work and live, and travel, in the faith and belief that they are citizens of the second largest democracy in the world? Or should they be conveyed that lockdown and special trains have redefined democracy in this land of unequal opportunities?

Sanghmitra S Acharya is Professor, Centre of Social Medicine and Community Health, School of Social Sciences, Jawaharlal Nehru University New Delhi \

SIGN UP FOR COUNTERCURRENTS DAILY NEWSLETTER