Written by Tanisha Nahar and Hadi Kangoo

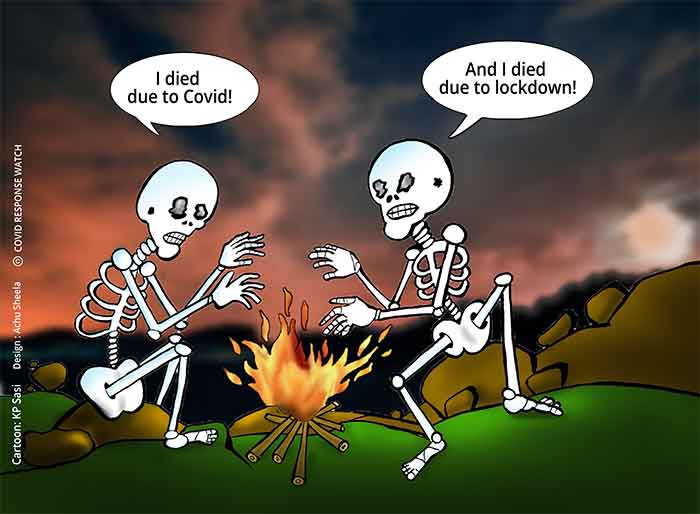

The coronavirus pandemic resulted in governments worldwide imposing strict lockdowns and enforced quarantines. It is common knowledge that ethical evaluations in policymaking are shunned due to political factors, and legislators, bureaucrats and policy analysts resist the challenges of moral evaluation. The Indian government’s one-day notice lockdown was a case-in-point of disregarding ethical considerations and resulted in the vulnerable people being unable to prepare for the consequences of the lockdown. Being in a position of privilege and having access to food, shelter, necessities such as medicine, internet, most of the well-off and rich fully supported the stringent lockdown and looked down upon people who defied it. However, as the news of hardships faced by the people began to pour in, it became evident that the cost of “greater good,” i.e. containing the virus was not borne equally by all members of the society. Moral and political philosopher John Rawls contends that fairness means that ‘the benefits and burdens of social cooperation are clearly and appropriately distributed’. Would any of the well-off and rich have wanted to be in the position of the stranded migrant workers, or the patients in need of access to healthcare, or workers in the informal economy living hand-to-mouth? A no-brainer answer would be that they would rather have privileged positions and avoid the hardships faced by vulnerable people.

Given that the answer to the chosen position is that of avoiding hardships, it can be concluded that fairness or equality weren’t criteria considered by the government in the decision to impose the lockdown. The overwhelming feeling is that the pandemic’s impact on the bottom rungs on the Indian society was disproportionate, increasing the food insecurity and economic vulnerability. The story of coronavirus is one of inequality, with the poor being the worst affected. There has been a massive increase in unemployment and corresponding fall in earnings. The impact of the coronavirus has encapsulated not only the country’s livelihood but also democracy. Laws and regulations (such as the labour laws) were amended in the name of coronavirus; however, this raised concern among stakeholders for being more exploitative of poor labourers.

Lockdown and the crisis that followed

The Indian Central Government issued the Disaster Management Act to give itself extraordinary powers to issue sweeping orders even in areas that normally fall under the purview of the State Government. With great power comes great responsibility. However, they renounced responsibility in a domain which comes under the Center even during normal times, leading to the worst-ever migrant crisis seen in India after the 1947 partition. It left the inter-state transportation of migrant workers entirely to the State Governments. This colossal mismanagement across the country combined with a sudden lockdown resulted in an unprecedented humanitarian crisis with millions of poverty-struck working-class Indians stranded, most left walking, cycling or dangerously hitchhiking home extremely long distances, sometimes more than thousands of kilometres, often penniless and on empty stomachs, leaving more than 170 people dead in accidents on the way.

India went from ‘don’t panic’ to nationwide lockdown in 6 days. On March 13, the government declared that the pandemic was ‘not an emergency’. Five days later, PM Narendra Modi urged everyone to observe a self-imposed ‘Janata’ curfew on March 22. This triggered an exodus of migrant workers, only to be struck down by incessant cancellation of trains by Indian Railways. At 8 pm on March 24, the prime minister on live television announced a three-week nationwide lockdown starting midnight – with just four hours of notice. Over the next few weeks, workers with very little cash reserves ran out of food and money. On March 26, authorities announced a doubling of food rations for Indians enrolled in the public distribution system, completely leaving out the millions of migrant workers with no ration cards clueless. After about 50 days into the lockdown, the government announced food support for them, but the actual disbursal took much longer.

Later, despite increasing coronavirus cases, the government arranged for their transportation by buses and special Shramik trains. However, the Indian Railways was only reduced to a transport agency, supplying a train only when both the origin and destination state jointly made a request. This proved to be a recipe for disaster – Indian states who rarely spoke to each other directly, had to coordinate via multiple channels of communication. This resulted in a political slugfest, which could have been avoided. Even if the idea was to decentralize decision-making, the Centre could have established an interstate council to facilitate better communication among states. They finally established a national migration information system to enable seamless movement across states, but only after 53 days into the lockdown.

Was this too little, too late?

This led to a huge inflow of workers across major states. To contain the spread of coronavirus, the government announced that the migrant workers would only be allowed to board trains after they secured medical certificates, which they would have to pay for. The process was harsh – workers first had to file an online form, secure certificated and then report to the nearest local police station to get a travel pass. Most of these workers lacked smartphones, websites were complex and often didn’t work, and the authorities didn’t even set up a help desk for them. Even those who could register, had no way of tracking their applications – never knowing for sure if they had secured a berth or not. This was in contrast to the relative ease with which middle-class Indians were travelling in special Rajdhani trains – wherein all they had to do was buy tickets online and show up at the station where they would be thermally screened upon entry. The poor had to walk large distances, wait days to get access to trains only to end up at wrong stations and be denied travel arrangements. Even after reaching their home states, they were treated as commodities and were sprayed by chemical disinfectants. According to the 2011 census, India has 5.6 crore migrants, while the actual number is estimated to be much more at 6.5 crores. The government only managed to transport a fraction of this humungous number.

It is painful for anyone to see one eat a dead animal for want of food, to see one walk thousands of kilometres in blistering heat for want of shelter, to see one being overrun by trains and trucks as one walks back to their homes, even as government’s own transport system stagnates in its yards. The government could have avoided this by giving ample notice to each lockdown, like most other countries such as Singapore, UK and NZ did. They could have announced a minimum wage guarantee of Rs. 5000-6000 per month through Jan Dhan accounts. While some nations like Germany, US, UK, Canada, Australia did it via employers, others resorted to direct benefit transfers or made retrenchment illegal. This could have been done via the infrastructure created by Aadhar or MNREGA.

Democracy and the lack of it

What the government did choose to do quickly was modify the labour laws, allowing flexibility to employers in terms of hiring and firing workers. Additionally, many states altogether suspended the labour laws in the wake of the pandemic, citing flexibility to businesses and employers to deal with curbs and lockdown. However, little to no regard was shown for the rights of the Indian labour force. In a report by Avantis Regtech which tracked over 1074 central and state laws and 58,726 compliances, around 272 changes in laws, rules and regulations were made, with almost a quarter of them across two areas – EHS (Environment, Health and Safety) and labour. Such changes to laws in the garb of the pandemic only serve the interests of employers and corporations, leaving the poor labourers without enough social security viz-a-viz worker wages and job security.

Healthcare and disparity in access to it

As if the lack of empathy and concern for the well-being of the poor and marginalized in terms of livelihood wasn’t enough, healthcare was another casualty of the pandemic. The overloaded publicly funded hospitals were unable to provide even basic treatments which took daylong waits. The lack of comprehensive ethical inquiry in the choices made by the government is also evident from the decision of the Mumbai Municipal corporation to unilaterally administer Dharavi residents with Hydroxychloroquine. The arguments given for mandatory administering of such drugs is based on the “greater good”, or the utilitarian argument. It is argued that the residents should take the drug to curb the virus spread. However, without reasonable research to back up this assumption of curbing the spread or the efficacy of the drug itself, this mandatory administering of drugs infringes of the personal liberty of citizens. The greater good vs the individual liberty dilemma posed here has its solution in medical research. If the efficacy of the drug is guaranteed and appropriate medical trials have been undertaken to ensure safety, then the greater good argument is acceptable. However, in the case of unproven efficacy and inconclusive results of trials, an individual should have the right to refuse such interventions. The precariousness of the lives of the poor stood exposed, as they were denied livelihood, and later forced to bear the brunt of the pandemic, while the lockdown primarily protected the rich who could afford to stay at home.

The debate on compulsory drugs/ vaccinations has once again come to light as governments worldwide start administering COVID-19 vaccines. The broader debate is of vaccines as a public good (rooted in utilitarian perspective) and the rights of individuals (of respecting bodily integrity). The historical positions on vaccinations and justifications using ethical theories remain applicable. The utilitarian perspective supports vaccination, and even those believing in the rights of individuals as paramount agree that those refusing vaccinations can be denied to use private and public properties such as schools, shops etc. However, the issue with COVID vaccine is not of consent or rights but that of safety and efficacy. The record time in which the trials were concluded and these vaccines were approved is unheard of. The WHO directive is one of non-mandatory usage and administering to those who accept it based on the merit of the vaccine. Therefore, mandating vaccines, unless backed by appropriate medical research, should be avoided. With all the discussion around whether the vaccines are indeed well researched and effective being justified, another aspect of the vaccination is the stark disparity in access to vaccines for the poor. While the government is in the process of planning rollout of vaccines for the 1.3 Bn population, there are concerns whether the existing vaccination network will be sufficient, and fears of nepotism and preferential vaccination for the influential and well-connected remain.

There is a need to recognize that with events as disrupting as the coronavirus pandemic, a deeper understanding of ethical considerations and their role in policymaking is gained. New dimensions are added to the understanding of what is ethical, just and fair. As policies and laws are formulated on the go to deal with the effects of the virus (e.g. the modifications to labour laws, etc.), the need to integrate ethical and moral evaluations in public policy analysis has never been more profound. To ensure the greater good and to protect the rights and liberties of individuals, including ethical evaluations in policymaking is a must.

Tanisha Nahar & Hadi Kangoo are second-year students from IIM Ahmedabad

SIGN UP FOR COUNTERCURRENTS DAILY NEWSLETTER