(This is an exclusive long-form essay that aims to provide the most comprehensive and incisive understanding of West Bengal Assembly Election 2021: the ground-shifting and momentous battle in post-Independent Bengal. This is the first of three parts. )

People and culture are shaped by their particular environment: geography, surroundings and climate, along with the tides of time and history.

Tattva is a Sanskrit word meaning ‘thatness’, ‘principle’, ‘substance’, ‘reality’, ‘truth’ or ‘essential nature’. By coining the neologism – Bengaltattva, or Banglatattoh (in Bengali pronunciation) – I wish to highlight the distinct ‘characteristics and tendencies’ – of the geographical region of the Indian subcontinent that is Bengal – which have developed through the long process of varied influences and the innate propensities of the region.

In this long-form essay, I will explain what is meant by Bengaltattva, and contrast it with Hindutva, while analyzing the pivotal high-stakes battle between the two, in the regard to the ongoing Assembly Election, whose consequences will mold the immediate future, and even the destiny, of India.

Finally, I will make few definitive, daring and even risky, predictions, by considering the prominent scenarios which are likely to transpire on, and after May 2, when the results will be declared.

So let’s proceed on an exciting, intriguing and revelatory journey from the ancient times, and arrive, at the third decade of the 21st century.

Bengaltattva

With the world’s tallest mountain range in the north and the world’s largest river delta in the south, Bengal is the region from where the waters of the Ganges, the Brahmaputra and the Meghna (now in Bangladesh) merge into the northeastern part of the Indian ocean – the Bay of Bengal – that is also the fertile womb of some of the fiercest cyclones on planet earth.

The land of Bengal is marked by the northern Himalayas, the central Rarh region, the southern Ganges or Bengal Delta and the coastal forest of Sunderbans – ‘beautiful forest’, named after Sundari or Sundri trees – where the famed Panthera tigris tigris, a specific native subspecies, popularly known as the Royal Bengal Tiger still roams and roars, in the mud-flat-lands, the swamps and the mangroves.

Mentioned as Vanga in earliest Sanskrit texts, ancient Bengal was the site of several Janapadas (‘footholds of a people’/ republics / kingdoms) of the Vedic period. The multiple Janapadas subsequently got absorbed into sixteen Mahajanapadas (600 BCE to 345 BCE) during which India’s first large cities arose since the end of the Indus Valley Civilization. This was also the period of the origin and rise of Buddhism and Jainism (and other non-Brahmanical ‘self-transformation-based’ sramana movements like Ajivika, Ajnana and Carvaka) which challenged the religious orthodoxy and the obsessive ritualism of the Vedic period.

Of the 16 Mahajanapadas, there were two in the East: Anga and one of the most prominent and prosperous, Magadha. Angas along with the Vangas are mentioned by the Jain Pragyapana in the first group of Aryans or Aryas (Indo-Iranian or Proto-Indo-Europeans).

According to Greco-Roman writers, when Alexander of Macedonia arrived in the northern region of the present Indian sub-continent (326 BCE), he was dissuaded from venturing further East, due to the inevitable confrontation with the formidable Nanda Empire of Magadha, and the massive ‘war elephant’ force of the Gangaridai: located by the modern researchers in the Ganges Delta of Bengal, especially within the domain of enigmatic Chandraketugarh, a river-linked ancient city, whose 2500 year old archaeological site has been unearthed near Kolkata, where several intriguing terracotta items from an angel-like Winged-Goddess to erotic art on plaques have been discovered; some of which even date back to the Pre-Mauryan times, and the latter period of the Indus Valley Civilization.

Subsequently Vanga or ancient Bengal was a part of the great Indian kingdom of the Mauryas that rose from Magadha in the East, and produced the legendary Emperor Ashoka whose emblems – the 24 spoke chakra and the pillar of four lions – are the symbols of the modern Republic of India.

After the decline of the Mauryan Empire, Vanga became the part of the Gupta Empire, based once again from the East, with its capital in Pataliputra, that is usually described – in the textbooks of history – as the ‘Golden Age of India’ .

The Gupta Empire nurtured a liberal cultural tradition. Kumaragupta I founded the most influential seat of learning, Nalanda Mahavihara – oldest university of the world – in the 5th century, that attracted students, monks and scholars – from as far as Central Asia, Tibet, Korea and China – who used the river-system-like network of the Old Silk Road – starting from Xian – that also traversed through Vanga.

After the Gupta dynasty, much of Vanga came under the control of the Hindu-Buddhist Kindgom of Gauda that produced the famous king Shashanka who reigned in the 7th century.

But it was under the Sanskrit-speaking Buddhist Pala Empire (750-1200), that the proto-Bengali-language and the proto-Bengali-culture originated, and a specific ethno-linguistic group of people, now known as the ‘Bengalis’, first emerged.

This emergence happened from the confluence of various communities, that ranged from a wide spectrum that included Dravidian-speaking people named Bang, the Vedda from Sri Lanka, the speakers of Indo-European languages and the peoples of Arabs, Persian and Turkish descent.

From such diverse origins, Bengalis – who took ‘birth’ under the Pala kings of Vanga / Vangala / Vangaladesa – began to develop further down the centuries, and eventually became the largest ethnic group within the Indo-Europeans, and the third largest in the world, after Han Chinese and Arabs.

The Palas brought about a golden era of Bengali history – the First Great Surge – that was marked by various advancements and growing prosperity. The very first literary work in an Abahatta – ancestor of Bengali language – was composed during the Pala Empire. It is called the Charyapada: a collection of mystical poems in the tradition of Vajrayana sect of Buddhism that developed in Vanga around 7-8th century.

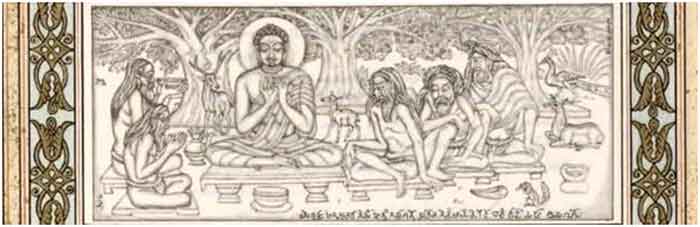

(Illustration by Nandalal Bose of the Buddha and his first five disciples in the handwritten copy of the Indian Constitution, now preserved in the National Museum in New Delhi)

Tarapeeth – associated now with the Hindu Goddess Kali – was originally a Buddhist site of goddess Tara; the stone feet of the missing ancient Tara idol still remain in the crematory ground of the popular pilgrimage town. The famed Buddhist scholar Asita Dipankara who went to Tibet was a Bengali. So was the influential mystic Tilopa, and his scholar disciple Naropa, who taught at Nalanda.

At their heights, the Palas – with their capital in Gaur whose archeological remnants are now divided by the current border between India and Bangladesh – captured the imperial city of Kanauj in the north, and extended their empire to the areas of present-day Pakistan.

The Palas also established diplomatic relations with Srivijaya Empire (on Sumatra, Indonesia), the Tibetan Empire and the Arab Abbasid Caliphate. The House of Wisdom – or the Grand Library of Baghdad – absorbed the mathematical, astronomical, literary and philosophical knowledge of Indian civilization due to the relations between Abbasid Caliphate and the Pala Empire.

All the Pala kings were dedicated patrons and builders of the Buddhist universities which flourished in the domain of Vanga. Gopala I founded the second oldest of India’s Mahaviharas in the 8th century – after Nalanda – Odantapuri (in present-day Bihar, whose name is derived from Buddhist Vihara, that simultaneously means monastery-temple-university).

Dharmapala – the most prominent of the Pala kings – patronized Nalanda, and founded Vikramshila (also in present-day Bihar) in the 8-9th century from where the second wave of Buddhism spread to Tibet. He also established Somapura (in present-day Bangladesh) in the 8th century that survived the flames of the marauding university-destroying forces of Bakhtiyar Khalji, the Turko-Afghan military general who was associated with the Gurids: Buddhists converted to Sunni Islam in the 11th century, in the Ghor region of present-day Afghanistan, whose Gurid dynasty preceded the Delhi Sultanate.

While being based from a part of Oudh (the present-day Mirzapur district in Uttar Pradesh), Bakhtiyar Khalji led the Islamic conquests of Eastern India / Vanga (1197-1206), which displaced Buddhism, and razed Nalanda, Vikramshila and Odantapuri.

But later, Somapura declined and crumbled slowly, due to lack of care and patronage, instead of being brought down in a flash, by steel and fire.

But the destruction of the world renowned Buddhist universities in the East didn’t happen under the Palas – the last imperial Buddhist Empire of India. It happened when the empire, which had started to decline from the late 11th century, was massively reduced – in the last 40 years of its 450 years of existence, when its capital also shifted to Mudgagiri (now Munger, in Bihar) – by the growing Hindu Sena Empire that began to rule Vanga – or the most parts of it – in the 11th and the 12th century.

The Sena Dynasty (1070-1230) was Brahmin by caste and Kshatriya by profession. The rulers traced their origin to the southern part of the Indian subcontinent that is the present state of Karnataka.

When Bakhtiyar Khalji and his horsemen swept into the rich and fertile land of ancient Bengal, the 80 year old King Lakshmana Sena (r.1178-1206), the Hindu ruler of Vanga, remained inert and ineffective in Nabadwip, Nadia. There was no organized resistance to Khalji. Several parts of Vanga – that time – had already defied the central rule of the Sena dynasty and a number of local chieftains had become the warlords of small areas; there was no coordination between them to defend the land, as a collective force. So the great universities of ancient Bengal, India, Asia and the world, were rendered completely vulnerable, and defenseless, to the raiders and destroyers, from the North.

Boosted by his success and sensing the weakness of the Senas, Khalji launched an unexpected attack on the city of Nababwip in 1203. The octogenarian king of Hindu Sena dynasty fled immediately, without a fight. Soon after, Khalji went on to capture Gaur, and become the first Islamic ruler of Vanga.

(But his reign was short-lived. In 1206, Khalji launched an audacious attack on Tibet in the lure of Mongolian horses and to control a part of the Old Silk Road – passing via the present-day Assam, Sikkim and Bhutan – through which tea , horses and other commodities were traded.

Khalji invaded Tibet. He went into the Chumbi Valley via the high mountain passes of Nathu La and Jelep La with ten thousand men, but returned vanquished, with around hundred.

Khalji – the destroyer of the ancient universities – was soon assassinated by one of his own generals, Ali Mardan, when he was bedridden with illness and depression – in Devkot, in present-day Bangladesh – in August 1206)

It was during the Pala Empire – which followed Mahayana and Vajrayana Buddhism, supported Shaivism and venerated learning and knowledge, and when the Bengalis first emerged as an ethno-linguistic group – the essential foundation of what I call the Bengaltattva was also established. It was based upon the emphasis on ‘art, culture and education’, ‘progressive liberalism’ and the ‘worship of the feminine force / Shakti’, inherited from the esoteric practices of Tantric Shaivism and Vajrayana Buddhism.

The next 800 years of history added five more entries to the list of Bengaltattva: ‘syncretism and plurality’, ‘renaissance’, ‘resistance, anti-colonialism and anti-imperialism’, ‘revolution’ and finally, ‘socialism’.

*

Ancient Bengal’s introduction to Islam began with the Arab traders in the 9th century and the Sufis in the late 11th century / early 12th century. When Bakhtiyar Khalji came to power, he also sent out Islamic missionaries; and many conversions also happened in a coercive manner.

But before that when the Brahmanical Hindu Sena Dynasty was on an ascendency from the early the 12th century, an atmosphere of conflict had developed between the equality-driven Buddhists and the caste-hierarchy-driven Hindus. This drove a lot of disaffected and subjugated Buddhists in the Hindu Sena strongholds of Eastern Vanga to get willfully converted by the Sufi missionaries, who absorbed local traditions and propagated egalitarian values.

This is how the imbalance in the population of the Hindus and the Muslims in Bengal originated, and accelerated later in the 16th century when the Mughals initiated agrarian development in the most fertile part of the Bengal delta – especially the Bhati region that lies mostly in the present-day Bangladesh – by clearing forests and creating Muslim-chieftain led farming villages centered around Sufi missions. Thereby, the eastern part witnessed a much higher concentration of Muslims than the western part that maintained a Hindu majority. This polarity in population distribution, eventually became the basis for partition of Bengal in 1947.

Vanga was ruled by the Delhi Sultanate from 1225 till 1352 that witnessed the synthesis of Islam and Bengali culture. Then Bengal became independent from Delhi rule with the establishment of Shahi Bangalah or the Sultanate of Bengal (1352-1575) founded by Persian Shamsuddin Ilyas Shah, where Bengali was the most widely spoken language and Persian was used as an official, diplomatic and commercial language. This period – that unified Bengal, after being divided into three provinces by the Delhi Sultanate – witnessed the Second Great Surge of Bengali history after the Pala era.

The Sunni Muslim monarchy with Indo-Turkic, Arab, Abyssinian and Bengali Muslim elites was known for its pluralism, welfare and maintenance of religious harmony. The influential spiritual movement by Shri Chaitanya Mahaprabhu – the great Indian saint, Vedantic theologian and founder of Gaudiya Vaishnavism – took place under the Sultanate. Shri Chaitanya had both Hindu and Muslim devotees.

Valmiki’s Ramayana and Vyasa’s Mahabharata were first translated into Bengali during the Bengal Sultanate whose royal court patronized and popularized the translations.

Bengali poet Maladhar Basu was conferred the title ‘Gunaraj Khan’. Sufi poet Nur Qutb Alam pioneered Bengali Muslim poetry by composing poems written half in Persian and half in Bengali and established this Dobhashi tradition. Bengali Muslim mystic writings flourished. The city of Sonargaon became a centre of publication and Persian literature.

More significantly, the economy took off with mint towns, shipbuilding, muslin production, cotton, textile, sericulture, wines, precious metals, ornaments and agricultural produce. Bengal began to be described by Europeans as the ‘richest country to trade with’ and by the Ming Chinese, as ‘rich and civilized’. The royal capital of Gaur – that was compared with Lisbon by the Portuguese – was the fifth-most populous city in the world in the year 1500. There were other prosperous cities like Pandua, Sonargaon, Bagerghat and Chittagong. The sultanate became a major sea-faring trading center. Bengali ships and merchants traded across the region, including Malacca, China and Maldives. Diplomatic relations were maintained with states in China, Europe, Africa, Central Asia and Southeast Asia. The Portuguese were granted permission to set up trading posts in coastal areas, and immigrants arrived in Bengal from everywhere, seeking refuge, work and better prospects.

The Bengal Sultanate became the Bengal Subah of the Mughal Empire – of Mongol descent that was simultaneously Central Asian, Islamic and Indian – in a gradual process that spanned several decades.

Babur defeated Sultan Nasiruddin Nasrat Shah of the Bengal Sultanate in the Battle of Ghaghra in 1529. Humayun occupied the Bengal capital of Gaur for several months during the invasion of Sher Shah Suri from Afghanistan, who re-introduced the silver coin rupiya, weighing 178 grains during his brief five-year rule of the 16 year old Suri Empire (1540-1556) that governed large parts of Northern and Eastern regions from the capital Sasaram, in present-day Bihar. Akbar completed the final absorption of Bengal with the Empire, by defeating the last reigning Sultan of Bengal Daud Khan Karrani in the Battle of Rajmahal in 1575 and by introducing uniform administrative subah– a term for province – by a royal decree in 1586.

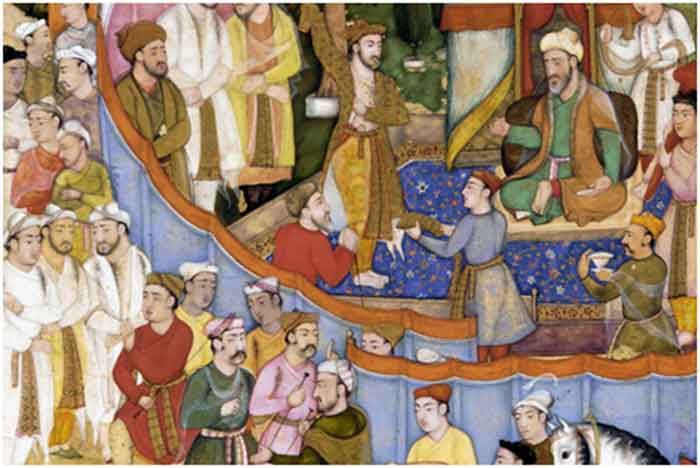

Under the Mughal Empire, Bengal Subah (formerly the Shahi Bangalah or the Sultanate of Bengal) witnessed the Third Great Surge of Bengali history.

In the 17th and early 18th century, Bengal reached her historical peak in terms of prosperity. New cities, like Dhaka and Murshidabad, were founded. The Mughals strengthened, improved and expanded agriculture, industries, trade and mineral extractions (such as saltpeter used in gunpowder), while maintaining the general ethos of syncretism and pluralism of the land.

India under the Mughal Empire contributed 24-26% to the world GDP; 50% of that share – 12-13% of world GDP – just came from the Bengal Subah. The living standards of the people and real wages in Bengal were among the highest in the world. Emperor Aurangzeb famously described Bengal as ‘the paradise of nations’ for her wealth and economy.

(Under the Mughal Empire, Bengal Subah reached the pinnacle of wealth and prosperity)

In the first decade of the 18th century, Mughal viceroys gave trading rights to the French, the Dutch and the British, and also allowed them to set up fortified trading posts in the strategic river-linked areas of Bengal which became Chandannagar, Chinsurah and Calcutta.

It must be recalled, the early advantage of the Portuguese arrival in Bengal was lost, because they were given the death blow in 1631 by Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan (who had a Hindu mother) – via his appointed Governor of Bengal, Qasim Khan – when the Portuguese – in the view of Mughal Empire – grew pre-colonial feathers, started shipping-off abducted people as slaves and converted orphaned children into Christianity.

The Portuguese – along with their factories and trading posts – were obliterated by Shah Jahan, and this set the stage for the British ascendency in Bengal.

During the second decade of the 18th century, the authority of the Mughal Court rapidly fell in Bengal, and the Nawabs of Bengal started to rule from their capital Murshidabad from 1717.

This was an era of poor governance, myopic thinking, bad policies and power-drunk high-handedness; wealth started to be hoarded by a tiny group of elites, and the wages started to fall for the commoners, along with their living standards.

It was during this time – around the middle of the 18th century – that the fabled wealth, resources and prosperity of Bengal became her own enemy.

From 1740s to the early 1750s, Bengal faced over a decade of brutal raids from the troops of the resurgent Hindu Maratha Empire who perpetrated relentless atrocities upon the western part of Bengal. Thousands of people, including merchants, weavers, farmers and cultivators were killed; factories burnt down; the economy, devastated. The Nawabs of Bengal had to pay annual tributes and exorbitant arrears to the Maratha invaders known locally as the ‘bargis’: from the Sanskrit word to seize.

Already weakened by the invaders and looters from the West, Bengal fell victim to the ‘corporate mercenaries’ from Far-West in 1757, when the Battle of Plassey was won – via a conspiratorial coup – by the private forces of the British East India Company led by the psychotic predator Robert Clive.

A coterie of local elites – that included turncoat military generals, politicians, bankers, businessmen and feudal families lost sight of the bigger picture. They conspired with Clive and connived with the Company, without grasping the full consequences of their actions, due to their narrow self-serving interests of wealth, power and control.

The Battle of Plassey, and subsequently the Battle of Buxar (1764), marked the beginning of the 200 years of humiliation for India, when her wealth, resources and civilizational vitality were efficiently conquered by the most extractive and well-organized ‘divide-and-rule’ colonial system on planet earth.

Economist Utsa Patnaik has conservatively estimated – in a book of essays published by the Columbia University – that the British Empire extracted 45 trillion dollars from Indian subcontinent. From the ‘gold-standard’ data of the past 2000 years of economic history of our world – painstakingly researched by economist Angus Maddison – we now know that from an average of 24-28% share of the world GDP for the much of human history till 1820, India’s share fell to 2-3% in 1947.

During the entire history of British rule, there was almost no increase in per capita income. During the last half of the 19th century, income in India actually collapsed by half. Average life expectancy crashed by a fifth from 1870 to 1920 and Bengal – along with India – suffered the most horrifying series of regular famines during the colonial rule, which she had never done before, in her long history.

During the same period, the Bengal Subah of the Mughal Empire became the Bengal Presidency of the British Empire. Linguistic, religious, community and caste identities were strongly revived and strictly demarcated as societal categories, which were often weaponized by the British colonizers, whenever necessary. Manusmriti was dug up from oblivion, misunderstood and popularized by the British as a ‘Hindu rule book’ that ennobled and appealed to the Brahmanical conservatives.

Calcutta rose from three muddy villages by the Hooghly, as the second most important imperial city on the planet, after London. The city became a cosmopolitan melting-pot of various groups of new immigrants – Armenians, Chinese, Baghdadi Jews, Greeks, Parsis, Afghans, Tibetans, Iraqis and more – and became the capital of colonial India from 1773 to 1911.

Patterns in life and in history often repeat themselves because of latent probabilities and fateful tendencies.

Just like the ancient times, the educational institutions (but based upon the British model) were once again founded first, after a gap of 600 years, in the East: Fort William College in 1800, Presidency University (formerly Presidency College and Hindu College) in 1817 and Serampore College in 1818; and then, the first modern multi-disciplinary university of India: Calcutta University in 1857. And several other critical institutions – such as The Indian Museum, The Asiatic Society, The National Library and The Archaeological Survey of India – got established.

Buried past of our ancient civilization was unearthed. Forgotten histories were pieced together to form new stories. We witnessed the most unique, pivotal and remarkable occurrences: the Bengal Renaissance and the Indian Independence Movement that led to our freedom in 1947; but not without leaving behind the indelible scar of Partition, and its consequences, which continue to play their visceral role in our politics and our consciousness.

*

The Renaissance in Bengal from the early 19th till the fifth decade of the 20th century – with a galaxy of icons who were born / worked / rose in prominence, within that time period – set the socio-cultural consciousness of Bengal, whose legacy still lives within us and makes us who we are.

The period witnessed an unprecedented phenomenon of a simultaneous awakening, culmination and development in the fields of education, science, arts, literature, social reforms, religion and spirituality.

Lalon Fokir, the Tagore family, Ram Mohan Roy, Iswar Chandra Vidyasagar, Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay, Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay, Michael Madhusudan Dutt, Kazi Nazrul Islam, Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay, Jibanananda Das, Satyendranath Bose, Jagdish Chandra Bose, Meghnad Saha, Ramakrishna, Maa Sarada, Swami Vivekananda, Rishi Aurobindo, Swami Prabhupada, Girish Chandra Ghosh, Nandalal Bose, Jamini Roy, Ganesh Pyne, Ramkinkar Baij, Uday Shankar, Satyajit Ray and more.

The Renaissance blended with the other great occurrence, the Indian Freedom Movement; and the confluence of socio-cultural surge and political movement, made Bengal, a prime leader in anti-colonialism, anti-imperialism, resistance, sacrifice and martyrdom.

Subhash Chandra Bose, Maulana Abul Kalam Azad, Khudiram Bose, Jatin Das, Bagha Jatin, Chittaranjan Das, Matangini Hazra, Surya Sen, Bidhan Chandra Roy, Rash Behari Bose, Badal Gupta, Dinesh Gupta, Benoy Basu and more.

When one reads the names of the inmates of the colonial Cellular Jail in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, one would immediately notice a higher percentage of Bengali and Punjabi names: the people from two regions, which eventually had to face Partition, and the horrors associated with it.

![]()

(Some of the icons who have created Bengal’s modern socio-cultural consciousness)

The partition of Bengal weakened it economically. West Bengal had to face the long-drawn challenges of the division, psychological trauma, communal violence, refugee crisis (that repeated again in 1971 in greater numbers), re-setting of governance structures and the initiation of post-Independence socio-economic development, with meager resources.

Even though Kolkata – now the third richest city of India, and the 15th most populated city in the world – was still the most prosperous, before it started to lose out to Mumbai and Delhi, and witnessed an exodus of big capital, big business and educated human resources, notably from the 1970s to the 1990s.

The great eastern winds from the Bolshevik Revolution and the Communist revolution of Mao, swirled over Bengal in the 1960s. Marxism and Naxalism captured the revolutionary consciousness of the educated youth. The Red Wave swept over the land, while establishing the Bengal comrades as a formidable force of national importance.

The 1970 film Pratidwandi (Adversary, Opponent or Competitor) by Satyajit Ray was based on the novel by Sunil Gangopadhay. It was the first film of Ray’s celebrated Calcutta Trilogy.

In that film, a job interviewee – Siddhartha: an educated middle class young man amidst social unrest and rampant unemployment – is asked about the most important event of the times. He says that more than the moon landing – that was more a matter of time and would have eventually happened – the defeat of the U.S.A in Vietnam because of the heroic fight by the Vietnamese men and women, inspires him the most, and he deems that to be more significant.

The Left government – led by Jyoti Basu of the Communist Party of India (Marxist) or the ‘CPM’ – cheekily changed the official name of Harrington Street to Ho Chi Minh Sarani because the U.S Consul General was located on that street. The Left wanted the U.S Consul General in Kolkata to forever remember Vietnam.

There were several glaring failures of the Left rule, from indulgence in ‘excessive antagonism of bourgeois industry’, which drove ‘capital and brains’ away from Bengal, to the nurturing of a ‘culture of political violence’, especially in a societal milieu that romanticized ‘the pistol and the bomb’, from the time of the Independence movement.

But the revolution also achieved the progressive rural land reforms which changed lives, stabilized societal harmony in terms of religion and caste (with Bengal currently having the lowest percentage of caste-related violence in India amongst all states), preserved the anti-imperial / anti-colonial mindset that rose during the freedom struggle and firmly established the ‘socialist’ narrative that favors people over profit, public welfare over corporate interests and David over Goliath.

India is a democracy, since 1947, and a market economy, since 1991. Economic and social benefits must percolate to all, not just a few, is a prime understanding of 21st century progressive socialism, where ‘communists’ – in the Indian context – now mean ‘democratic market socialists’.

The decades of Nehruvian socialism followed by decades of Left ideology has now made socialism – or ‘democratic market socialism’ – the default mode of Bengal. The citizens expect the government to be pro-people, and fulfill the role as the facilitator of socio-economic justice, especially in a low middle income developing nation like India, that is yet to overcome the fundamental challenges: lack of basic infrastructure, adequate job creation, illiteracy, poverty, hunger and malnutrition.

Corporations primarily care about their customers, shareholders and profit, while a government has to fulfill constitutional duties, display moral sense and abide by a ‘social contract’ towards all people, irrespective of their political affiliation, demographics and voting preference.

But when a government – fattened by private capital linked to vested interests – begins to think like a corporation – focused obsessively on trapping voters, satisfying funders and acquiring material gain – it loses the vital genes of being a true government, and becomes a deceptive hologram, a hollow institution and a trader’s desk.

Contemporary 21st century socialism should ideally prevent governments from becoming ‘fully privatized’, and thereby safeguard their moral authority and their ability to serve public interests.

Socialist thinking has become deeply entrenched in Bengal. It hangs in the air as an essential ingredient of the climate. Everyone gets drawn towards it – consciously or unconsciously – when they are on the soil of Bengal.

The present All India Trinamool Congress (AITC, or popularly known as the TMC) government led by Mamata Banerjee – that displaced the 34 year rule of the Left in 2011 – is also predominantly ‘left of centre’ in socio-economic outlook, policies, schemes and programs.

From the 8th century Pala Empire to the third decade of the 21st century, the journey of Bengal – while witnessing three Great Surges and a Renaissance – has successfully established the Bengaltattva or the Banglatattoh: an unique concoction or a specific blend of traits, created by the 8 aspects / sub-tattvas: ‘art, culture and education’, ‘progressive liberalism’, ‘worship of the feminine force / Shakti’, ‘syncretism and plurality’, ‘renaissance’, ‘resistance, anti-colonialism and anti-imperialism’, ‘revolution’ and ‘socialism’

****

(To be continued: Part Two: Bengaltattva and Hindutva)

(The author gives permission to any publication that wishes to re-publish / translate this essay or any part of it. However, the original online publisher has to be mentioned, and a link to this essay has to be provided)

Devdan Chaudhuri is the author of the novel ‘Anatomy of Life’ published by Picador India. He writes short stories, opinion pieces and essays on politics and culture which have appeared in various publications. Apart from fiction and non-fiction, he also writes poetry. His poems have featured in ‘Modern English Poetry by Younger Indians’ published by Sahitya Akademi, India’s National Academy of Letters. He is also one of the contributing editors of The Punch Magazine: India’s monthly online magazine of Art, Culture and Literature. He lives in Kolkata.

GET COUNTERCURRENTS DAILY NEWSLETTER STRAIGHT TO YOUR INBOX