Introduction

Though India had a distinction of electing a woman Prime Minister in 1966 (Mrs. Indira Gandhi) and an Indian (Mrs. Vijay Laxmi Pandit) became the first woman President of the UN General Assembly in 1953, the position of women in India is very low and their rights are rarely protected. Problems like dowry, sati or self-immolation of widows, child marriage, child widows, female infanticide, honour killings, devdasi system and other innumerable forms of discrimination are common in India. The status of Hindu and Muslim women and their rights is highly influenced by the customary laws based Code of Manu and Shariah respectively. Let us elaborate this further.

Manusmriti contains many discriminatory principles, e.g., in the absence of a son it asks a woman wishing to obtain a progeny shall lie down, with a younger brother or with a relation of her husband for the procreation of a son. It prescribes that a wife should wait for eight years for her husband, who is away for studies or for achieving fame, whereas it allows a husband to wait only for one year for a hostile wife and then permits him to remarry other wife or marry again if his earlier wife has given birth only to daughters. It also declares that a woman should never be independent − “as a daughter she is under the surveillance of her father, as a wife of her husband, and as a widow of her son.”

The Indian Constitution guarantees and posits formal equality under Articles 14, 15, and 16. Art. 15 (1) prohibits discrimination on grounds of religion, race, caste, sex, or place of birth. However, under Article 15 (3) power is vested in the State to make special provisions (affirmative action) for women and children. Under Directive Principles of State Policy, both men and women are entitled for equal pay for equal work (Art. 39). A provision for maternity benefit to women is provided in Article 42. Article 44 directs the State to enact Uniform Civil Code (covering family laws) to nullify the gender bias in different personal laws that are in operation in India. India has international obligations to respect women’s human rights and eliminate gender-based discrimination as it has ratified the UN Covenants on Human Rights on 10 April 1979 and CEDAW on 9 July1993. India signed CEDAW in 1980 but ratified it after 13 years. Despite the constitutional prohibition of any discrimination on the ground of sex and India’s CEDAW obligations, women in India face discriminatory treatment both in private and public spheres.

Domestic Status of CEDAW in India

In India treaties are not self-executing. The provisions of treaties do not form automatically part of the domestic law. Implementing legislation is necessary to give effect to their provisions. In common law countries customary international law is considered as a part of the law of the land as long as they are not inconsistent with national statutes. Also, in these countries the courts refer to international treaties ratified by their country as a source of guidance in constitutional and statutory construction when their laws are uncertain, ambiguous or incomplete. In India, the Parliament, executive, and judiciary have the power to interpret a treaty. In certain cases, a treaty might be implemented by the exercise of the executive power of the President in accordance with Article 53 of the constitution. Article 51(1) of the Indian constitution further provides that the State shall “foster respect for international law and treaty obligations”. Indian courts have endeavoured to interpret the constitution and laws in consonance with the provisions of the international treaties ratified by India.

Before we study the role of India in implementing CEDAW provisions to empower women politically, socially, educationally, and economically, it is important to learn the main provisions of CEDAW, which are summarized below:

Article1 provides the definition of “Discrimination”. It states the term

“discrimination against women” shall mean any distinction, exclusion or restriction made on the basis of sex which has the effect or purpose of impairing or nullifying the recognition, enjoyment or exercise by women, irrespective of their marital status, on a basis of equality of men and women, of human rights and fundamental freedoms in the political, economic, social, cultural, civil or any other field.

Article 2: Governments shall take concrete steps to eliminate discrimination against women;

Article 3: Governments shall take all appropriate measures to ensure that women can enjoy basic human rights and fundamental freedoms;

Article 4: Governments can adopt temporary special measures to accelerate equality for women, i.e., affirmative action;

Article 5: Governments shall take appropriate measures to eliminate sexist stereotyping;

Article 6: Governments shall take all measures to stop trafficking and exploitation of women for prostitution;

Article 7: The right of women to vote, to participate in forming and implementing government policies and to join public and political organizations;

Article 8: Right of women to represent the country at international level;

Article 9: Equal rights with men to keep and change their nationality and to grant their

nationality to their children;

Article 10: Women and girls should receive career and vocational guidance and have access to education opportunities on par with men or boys;

Article 11: Women have an equal right to work with men, which includes pay, promotions, training, health and safety;

Article 12: Women have the right to family planning services;

Article 13: Woman shall have a right to family benefits, bank loans, mortgages, and other forms of financial credit;

Article 14: Governments should undertake to eliminate discrimination against women in rural areas so that they may participate in and benefit from rural development;

Article 15: Women are to be equal before the law;

Article 16: Women have the same rights as their husbands in marriage, childcare and family life.

CEDAW provides for a 23 member monitoring Committee of independent experts to review the periodic reports submitted by ratifying states. This CEDAW Committee, after reviewing State Parties reports critiques the role of the State in implementing the treaty provisions. It makes recommendations to the State to undertake legislative and executive measures to improve its record of complying with women’s human rights obligations.

While ratifying CEDAW, India made two Declaratory Statements and one reservation. These are: (i) Articles 5(a) and 16(1) call for elimination of all discrimination of against women in matters relating to marriage and family relations. India declares that it shall abide by these provisions in conformity with its policy of non-interference in the personal affairs of any community without its initiative and consent. (ii) Article 16 (2) calls for making the registration of marriage in an official registry compulsory. India declares that it agrees to the principle of compulsory registration of marriages. However, failure to get the marriage registered will not invalidate the marriage particularly in India with its variety of customs, religions and levels of literacy. (iii) Article 29 (1) establishes compulsory arbitration by the International Court of Justice of disputes concerning interpretation of CEDAW. India declares that it does not consider itself bound by this provision.

As of March 2021, India has submitted five periodic reports. The first report (due on 8 August 1994) was submitted on 10 March 1999. The second and third reports (due in 1998 and 2002 respectively) were submitted on 19 October 2005 as a combined report. The combined fourth and fifth report was submitted on 6 July 2012. The next report was due in July 2018, but not yet submitted. Let us discuss here the combined fourth and fifth report submitted in 2012. It was reviewed by CEDAW Committee in 2014. The report provides details of various legislative measures undertaken and schemes launched to advance gender equality between 2006 and 2011. These were, among others, (i) The Hindu Succession (Amendment) Act, 2005 removes gender discriminatory provisions in the Hindu Succession Act, 1956 and gives the daughter the same right as the son to inherit the parental property. Now a female heir or widow upon remarriage can ask for partition of the joint family property, which was not allowed in 1956 Act. (ii) The Personal Laws (Amendment) Act, 2010 has amended the Guardians and Wards Act, 1890 and the Hindu Adoptions and Maintenance Act, 1956, and the mother was included as guardian along with the father. (iii) The RTE, 2009 provides for compulsory and free education to all children of 6-14 years of age. The Act has special provisions for girl child education, including out of school girl child. It further mandates the private schools to ensure at least 25% of its seats are available for marginalized households. (iv) Maternity leave for government and public sector employees has been increased from 135 days to 180 days. Women having children can avail child care leave for a maximum period of two years. Paternity leave of 15 days is also granted to government and public sector employees. (v) India has ratified the United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime and its two protocols, including the Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, especially Women and Children, in May 2011. A comprehensive scheme for prevention of trafficking and rescue, rehabilitation, re-integration and repatriation of victims of trafficking for commercial sexual exploitation namely “Ujjawala” is being implemented since 2007 under which 86 rehabilitative homes have been sanctioned to accommodate nearly 4000 women victims. The Committee welcomed the progress achieved by India since the consideration of its last combined reports in 2007 in undertaking legislations like, (a) Criminal Law (Amendment) Act, in 2013; (b)Prohibition of Employment of Manual Scavengers and their Rehabilitation Act, in 2013; (c) National Food Security Act, in 2013; (d) Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace (Prevention, Prohibition and Redressal) Act, in 2013; (e) Protection of Children from Sexual Offences Act, in 2012; and (f) Right to Education Act 2009. However, CEDAW Committee called upon India (a)To promptly review the continued application of the Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act in accordance with the recommendation of Justice J.S. Verma; (b)To amend and/or repeal the Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act so that sexual violence against women perpetrated by members of the armed forces is brought under the purview of ordinary criminal law and, pending such amendment or repeal, to remove the requirement for government permission to prosecute members of the armed forces accused of crimes of violence against women or other abuses of the human rights of women and to grant permission to enable prosecution in all pending in all pending cases; (c) To amend section 19 of the Protection of Human Rights Act and confer powers to the NHRC to investigate cases against armed forces personnel, in particular cases of violence against women; (d) To ensure the full and effective implementation of the Communal Violence (Prevention, Control and Rehabilitation of Victims) Bill, as soon as it has been enacted (regrettably, it has not yet been enacted); (e) To adopt an integrated policy to enhance the living conditions of women/ girls who survived the Gujarat riots; (f)To ensure that women in the north-eastern states participate in peace negotiations and in the prevention, management and resolution of conflicts in line with Security Council resolution 1325 (2000); (e)To adopt an integrated policy to enhance the living conditions of women and girls who survived the Gujarat riots; (f) To speedily enact legislation to require compulsory registration of all marriages.

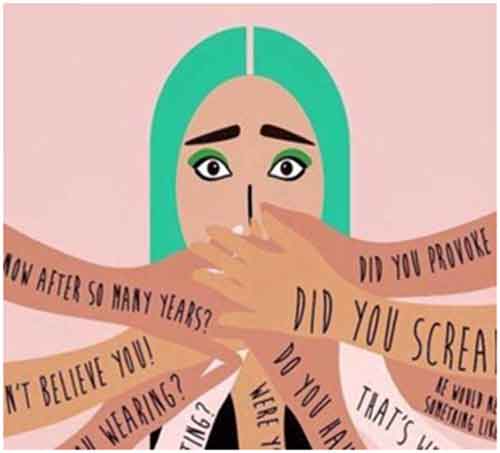

The Committee reiterated its view that India’s declarations and reservation to articles 5 (a) and 16 (1) and (2) of CEDAW are incompatible with its constitutional guarantees of equality and non-discrimination. It is also concerned at the persistence of patriarchal attitudes and deep-rooted stereotypes entrenched in the social, cultural, economic and political institutions and structures of Indian society and in the media that discriminate against women. It further expressed concern about the persistence of harmful traditional practices, such as child marriage, the dowry system, so-called “honour killings”, sex-selective abortion, sati, devadasi and accusing women of witchcraft. It is particularly concerned that India has not taken sufficient, sustained and systematic action to modify or eliminate such harmful practices.

The Committee is also concerned about the delay in the adoption of the Constitution (108th Amendment) Bill, intended to ensure a 33% quota for women in Parliament and in the state legislatures, which has been pending before Parliament since 2010. The Committee called upon India to use the Beijing Platform for Action in its efforts to implement CEDAW provisions. Also, it encouraged India to ratify the Optional Protocol (OP) to the Convention. Our record in this regard in comparison to four SAARC countries is poor, as OP was ratified by Bangladesh in 2000, Sri Lanka in 2002, Maldives in 2006 and Nepal in 2007.

The alternative reports of UN accredited NGOs, however, were highly critical of India’s performance in implementing CEDAW obligations. It is true that official reports normally present a rosy picture of domestic implementation. The real situation on ground can only be found in shadow reports of NGOs like, Amnesty International and the National Alliance of Women (NAWO). The Committee members read these reports before reviewing State reports and ask questions to state representative on the basis of information contained therein regarding noncompliance of CEDAW provisions. They also critique the State for failure to address violations of women’s rights.

(c) Role of Supreme Court to invoke CEDAW

The Supreme Court and the High Courts have been invoking international obligations in their judgments while deciding petitions seeking to enforce the constitutional provisions on fundamental rights. The courts have invoked international obligations to interpret and expand the scope of these constitutional provisions in the following cases.

Between 1950 and 1975 the Supreme Court was not very active in adjudicating cases of rape, restitution of conjugal rights of husband (where wife stays away for the purpose of doing job), and adultery by husband. Its role was very narrow, legalistic and very conservative. It was only after 1975, i.e., International Women’s Year that many High Courts and the apex Court began to recognize woman’s rights and gender equality. It was through cases of PIL on women’s rights that these Courts took progressive stand to deliver innovative judgments to advance gender justice. In fact, the Supreme Court has effectively invoked CEDAW in advancing gender justice in a number of cases, as the following cases illustrate.

In Vishaka vs. State of Rajasthan, regarding “sexual harassment” of women at the workplace, the Court was more forthright in the use of human rights instruments for interpreting the constitutional provisions as well as the legal position of treaties that are not enacted as law. Chief Justice J.S. Verma observed:

In the absence of domestic law occupying the field, to formulate effective measures to check the evil of sexual harassment of working women at all place, the contents of International Conventions and norms are significant for the purpose of interpretation of the guarantee of gender equality, right to work with dignity in Articles 14, 15, 19(1) and 21 of the Constitution and the safeguards against sexual harassment therein. Any International Convention not inconsistent with the fundamental rights and in harmony with its sprit must be read into these provisions to enlarge the meaning and content thereof, to promote the object of the constitutional guarantee. This is implicit from Article 51 (c) and the enabling power of parliament to enact laws for implementing the International Conventions norms… [Italics added].

The Court further stated that in the absence of domestic law on the particular aspect, these Conventions and norms as ratified by India could be relied by the Court to formulate guidelines for enforcement of fundamental rights. The Court had framed Guidelines concerning Sexual Harassment of women at workplace, which continued to be applied as law till Parliament enacted a law on the subject.

In Geeta Hariharan vs. Reserve Bank of India (1999), a provision of Hindu Minority and Guardianship Act, 1956 was challenged for its constitutionality, which regarded father as the natural guardian of the son. The Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of the provision but accorded a different interpretation to the word “after” in the section to mean “in the absence of” rather than “after the death of the father”. Such an interpretation, in court’s view, was in keeping with the mandate of gender equality enshrined in the Constitution, the CEDAW, and the Beijing Declaration, which directs all state parties to take appropriate measures to prevent discrimination of all forms against women.

In AK Chopra case judgment of 1999, the Supreme Court referred not only to International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (which India ratified in 1979) but also to CEDAW and observed that sexual harassment of females at the place of work is incompatible with the dignity and honour of a female and needs to be eliminated.

In case of Anuj Garg vs. Hotel Association of India (2008), the Supreme Court confirmed the Delhi High Court judgment and held that Section 30 of the Punjab Excise Act, 1914 that prohibit employment of “any woman” in any part of such premises in which liquor or intoxicating drug was served was discriminatory.

In K. Krishnamurthy (Dr.) vs. Union of India, (2010) and Union of India vs. Rakesh Kumar, (2010) the Supreme Court upheld reservation of seats for women in panchayats. It may be noted that Article 4 of CEDAW provides for affirmative action for women.

India’s efforts to translate MDGs & SDGs into Reality

Since most States are not serious in implementing all CEDAW provisions and the 1995 Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action and India is no exception to this trend, the UN adopted, in year 2000, 8 Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) and in 2015, 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The MDGs had to be achieved in 15-year time-bound period, i.e. by 2015, and the SDGs have to be achieved by 2030. MDG-3 (promote gender equality and empowerment of women) and SDG-5 (Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls).

Gender equality lies at the heart of the 2030 Agenda of SDGs. SDG-5 cuts across all 17 SDGs within the Agenda and sets the following ten targets:

- End all forms of discrimination against all women and girls everywhere;

- Eliminate all forms of violence against all women girls in the public and the private sphere, including trafficking and sexual and other types of exploitation;

- Eliminate all harmful practices such as child, early and forced marriage and female genital mutilation;

- Recognize and value unpaid care and domestic work through the provision of public services, infrastructure and social protection policies and the promotion of shared responsibility within the household and the family;

- Ensure women’s full and effective participation and equal opportunities for leadership at all levels of decision-making in political, economic and public life;

- Ensure universal access to sexual and reproductive health and reproductive rights;

- Undertake reforms to give women equal rights to economic resources, as well as access to ownership and control over land and other forms of property, financial services, inheritance and natural resources, in accordance with national laws;

- Enhance the use of enabling technology, in particular ICT, to promote the empowerment of women; and

- Adopt and strengthen sound policies and enforceable legislation for the promotion of gender equality and the empowerment of all women and girls at all levels.

Although India has initiated many schemes and policies (like SABLA (Rajiv Gandhi Scheme for Empowerment of Adolescent girls, Matritva Sahyog Yojana, Swadhar homes scheme, Ujala scheme (since 2007), Ujjwala scheme to provide LPG connections, and Beti Padao, Beti Bachao) to promote gender justice, we are far behind in achieving full gender equality. Here we are providing empirical data to show India’s poor record in achieving the CEDAW obligations, Beijing commitments, MDGs and SDGs (as India has been party or signatory to all these documents). The following data and analysis reveals that India lags far behind in making appreciable progress to implement them.

- The fact that India is ranked 125th on the Gender Inequality Index of 159 countries in 2015 and 87th as per Global Gender Gap Index among 147 countries reveals that it is far from achieving the target of ending all forms of discrimination against women.

- Violence against women (VAW), crimes against women (CAW) and domestic violence against them are increasing. Crimes like rape, kidnapping, molesting, eve-teasing, dowry deaths are increasing. In 2011, there were 24,206 rape cases (90% of the perpetrators are known to the victim), 8,570 sexual harassment cases and 42, 968 eve-teasing cases registered in police stations in India. During 2001-2013 there were 263,000 rape cases registered in India and every 20 minutes one rape occurs. In 2013, 300,095 total cases were reported against women but unfortunately the conviction rate was unsatisfactory with just 22%in 2013, 21%in 2012, and 27% in 2011. The national capital Delhi accounts for approximately 21% of all crimes against women (CAW), despite being home to less than 1.4% of India’s population. There was a 27% increase in 2014 over the previous year on reporting on rapes and sexual assault. Jagori, a women’s NGO, reported that 75% of women respondents identified gender as the main contributory factor to their lack of safety in urban spaces and cities. The UN Special Rapporteur on VAW noted in 2014 that there are high levels of tolerance in society with regard to violence.

- Though India could not achieve gender parity in school education by 2015, there was an improvement in the enrolmement of girls in many regions. As per 2011 census data there were 933 females per 1000 males. The female literacy was 65.46% with the male literacy rate at 81%. Similarly, girls are lagging behind boys in school enrolment. The top five states for girl’s education are Kerala, Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu, Telangana and Jammu and Kashmir, while the five bottom states are Rajasthan, Gujarat, Odisha, Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh.

- The health situation of women is still not satisfactory in India; MMR was 301 for 100,000 live births in 2000 but it declined to 167 in 2013 due to better health and medical facilities. It may be noted that SDGs target is to bring down MMR to 70 per lakh, IMR to 12 and IMR to 25 per lakh by 2030. However, thousands of women still die annually in delivery complications due to following major causes: haemorrhage (30%), anaemia (19%), sepsis (17%), obstructed labour (10%), toxaemia (8%) and others (17%). Institutional delivery increased during 2006-2011 from 42% to 84% due the launch of National Rural Health Mission by Government of Dr. Manmohan Singh. Further, NFHS-4 reports women in the reproductive age are undernourished and over 53% are anaemic. Thus the male-female relationship is not egalitarian but discriminatory in India.

- In Beijing +20 Conference (2015) India admitted that it has gender inequalities. For instance, India has decreased its spending on education from 4.4% of GDP in 1999 to around 3.71% as per 2017 budget estimate, undermining the work done in getting more children into school and prospects for improving its poor quality of education. It may be recalled here that India had made commitment at 1995 Beijing Conference to increase investment in education to 6% of GDP, with a major focus on women and girls.

- According to Wada Na Todo Abhyan, the Parliamentary Standing Committee has pointed out the scarcity of Girls’ Hostels as one of the major reasons for high dropout rate as under Rashtriya Madhyamik Shiksha Abhiyan (RMSA), out of 2,225 girls’ hostels, only 802 were made functional. This problem is severest for children in Educationally Backward Blocks. Budget for these is meager.

- According to the World Bank, 32.7% (40 crore) Indians live in poverty (on less than $1.25 a day). Actually in poor households women and girls are the worst sufferers due to intra-household discrimination and they usually work as informal and casual workers on a contract basis. Further, there are 2.3 crore women-headed households in India (Census 2011) and amongst them 1.4 crore are deprived. They are mostly widows, separated, divorced or single women. In fact, only 4% of married women head households. Thus we find feminization of poverty in India.

- There have been a near absence of women’s ownership of means of production (land, house, factory, institutions, and trade) in India; at the most they have partial control over their ornaments (streedhan). Power emanates from the control over various resources; women’s less control actually means less power for women.

- Political representation in Parliament and Assemblies has not increased, and the government has failed to adopt temporary affirmative action legislation as per CEDAW’s article 4. Last Lok Sabha had 11.8% women members. India’s rank on this is 148 in the 193 UN members, whereas our neighbours’ tally is much better: Nepal with 29.6%, Pakistan with 20.6% and Bangladesh with 20.4%. The Indian example of low representation therefore is curious and difficult to explain, as many democracies are moving up the ladder of women’s political reservation. The Women’s Reservation Bill was pending since 1996 was passed by the Rajya Sabha only in 2010 as the Constitution (108th Amendment Bill) providing for 33% reservation for women in the Parliament and the Assemblies was passed by but till this day the Lok Sabha has not adopted it due to lack of support from male members of all political parties.

Conclusion

Despite constitutional guarantees of the principle of equality and non-discrimination to all citizens, India’s ratification of CEDAW and signing of the Beijing Platform for Action, MDGs and SDGs gender inequality gender discrimination prevails widely. Effective implementation and preventive measures fall far short of requirements. The issues of impunity and immunity enjoyed by the perpetrators under the guise of tradition, culture and factors, and the low rates of prosecution and conviction undermine the drive to reduce violence against women. The situation will improve if India withdraws reservation to Article 16 of CEDAW and reforms the personal laws of religious groups and implements the recommendations and suggestions of the CEDAW Committee and the reports of the civil society organizations.

Abdulrahim P. Vijapur holds M.A. in Political Science from Karnatak University, M. Phil. & Ph.D. from Jawaharlal Nehru, university and LL.M. in international human rights law from University of Essex, the United Kingdom. He worked as Professor of Political Science till February 2020 in Aligarh Muslim University. He worked as Chairman (2010-2013) of its Department of Political Science, and Director (2010-2013) of its Centre for Nehru Studies. He specializes in International Human Rights Law, Minority and Dalit Rights, Federal Nation-building in India, Islamic concept of rights and women’s rights. Previously he was Visiting Professor in Human Rights Studies in Jawaharlal Nehru University. He has been a Visiting Professor to ICCR (Indian Council of Cultural Relations) Chair at the Carleton University, Ottawa, Canada (2013-14). He also taught at South Asian University, New Delhi. During 2005-2007 he was Professor, Ford Foundation Endowed Chair in Dalit Studies at Jamia Millia Islamia, New Delhi. During 1996-1999 he was Director, Centre for Federal Studies, Jamia Hamdard, New Delhi.

Email: [email protected]

GET COUNTERCURRENTS DAILY NEWSLETTER STRAIGHT TO YOUR INBOX