The global scene is deeply disturbing. The wealth of billionaires is increasing even as the starvation-scarred world cries for help; astronomical surges in inequality are pushing an ever greater number of people into a state of pure deprivation; the repressive powers of capitalist states all over the world are being steadily strengthened to silence the growing disquiet in streets and slums; the value of life is plummeting as the poor are wantonly killed for demanding what is theirs; and innumerable people are being sacrificed for the continued existence of a thoroughly decadent, greedy elite.

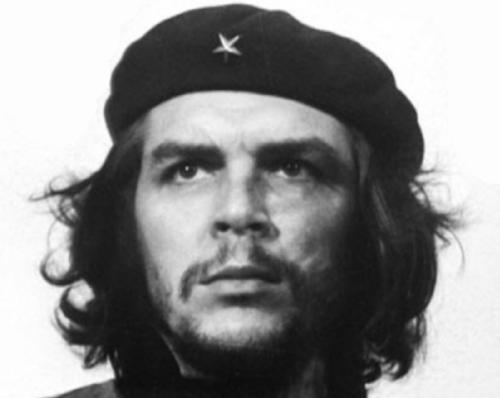

In brutal times like these, June 14, 2021 – the 93rd birth anniversary of Ernesto Che Guevara – stands as a day of militant introspection, inviting us to reflect on the infinite capacity one should have to advance the cause of revolution. Che was a person whose life was indissolubly intertwined with the goal of liberation. He never submitted to the heavy force of dehumanizing oppression, always upholding and emphasizing the world-shaping capacities of human beings.

For him, humanity was not just an objectified thingness, sealed in the ungroundedness of alienation. Instead, it was a fluid social relation, enmeshed in the flexible fabric of endless change-stability-transformation. History referred to the innumerable instances in which the people used the inexhaustible ideality of their inherent potentialities to openly confront the concrete phenomenality of structural conditionedness. Che derived these radical orientations from lived experience, from a direct intervention in the arena of revolutionary processes.

Guatemala

In 1953, in Mexico, Guevara met Hilda Gadea, a revolutionary belonging to Peru’s American Popular Revolutionary Alliance (APRA). She familiarized Che with Marxist theory and in the radical ideologies then convulsing the region. They moved to Guatemala in September 1954, as the government of Jacobo Árbenz had taken office, elected by the votes of workers and peasants hoping for end to the misery inflicted upon them by the ultra-wealthy oligarchy of semi-feudal landlords and a comprador bourgeoisie. Che went to work, under programs sponsored by the Árbenz government, in the barrios of indescribable poverty and wretchedness that stood as a clear testimony to the brutalizing impact of imperialism.

The Árbenz administration attempted to push through a moderate land reform agenda; this threatened the US-based United Fruit Company which owned a lot of land in Guatemala. To his aunt Beatriz, Che wrote: “I have had an opportunity to go through the land owned by United Fruit, and this has once again convinced me of the vileness of these capitalist octopuses. I have sworn before a portrait of old, tearful Comrade Stalin not to rest until these capitalist octopuses have become annihilated. I will better myself in Guatemala and become a true revolutionary.”

The CIA began scheming against Árbenz, the goal being: to “remove covertly, and without bloodshed if possible, the menace of the present Communist-controlled government in Guatemala”. Through a secret operation named PBSUCCESS, the US overthrew Árbenz in a coup in 1954 and installed retired Colonel Carlos Castillo Armas who said, “If it is necessary to turn the country into a cemetery in order to pacify, I will not hesitate to do so.”

Meeting Castro

Che immediately fled to Mexico to avoid Guatemala’s right-wing death squads which had him targeted. In Mexico City, he encountered Fidel Castro and other Cuban revolutionaries who were in forced exile after the failed Moncada uprising of July 26, 1953. Castro recalled:

“I first met Che one day in July or August 1955. And in one night…he became one of the future Granma expeditionaries, although at that time the expedition possessed neither ship, nor arms, nor troops. That was how, together with Raul, Che became one of the first two on the Granma list…

In those first days [Che] was our troop doctor, and so the bonds of friendship and warm feelings for him were ever increasing. He was filled with a profound hatred and contempt for imperialism, not only because his political education was already considerably developed, but also because, shortly before, he had had the opportunity of witnessing the criminal imperialist intervention in Guatemala through the mercenaries who aborted the revolution in that country.

A person like Che did not require elaborate arguments. It was sufficient for him to know Cuba was in a situation and that there were people determined to struggle against that situation, arms in hand. It was sufficient for him to know that those people were inspired by genuinely revolutionary and patriotic ideals. That was more than enough.”

Here, we encounter another unique characteristic of Che’s thinking: the ability to deeply connect with emancipatory struggles all over the world. This type of cosmopolitanism was summed up by him in the following words: “Every true man must feel on his own cheek every blow dealt against the cheek of another.”

Che’s strong internationalism presupposed the absence of dogmatism. The latter, in its quest to mold reality according to its own theoretical dictates, is unable to appreciate the particularity of different struggles and ends up indifferently incorporating them into a matrix of bland universalism. Che avoided this mistake, thus succeeding in synthesizing practice and theory.

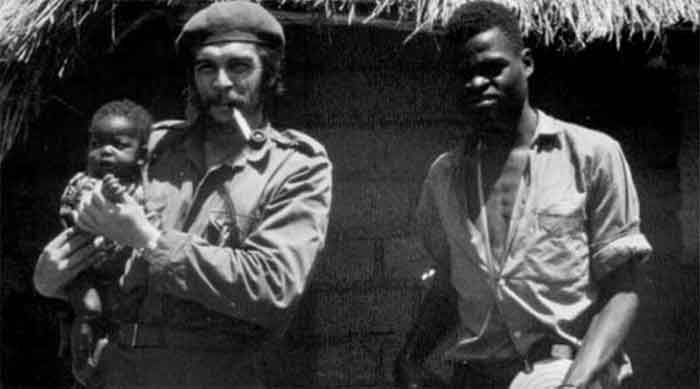

Instead of clinging to hardened ideological abstractions, he dissolved them in the acid bath of material realities. Events were understood not through preconceived ideological constructs but a dialectical lens which ensured that practice was guided by a theory that would necessarily be rethought in light of the outcomes of this practice. This explains his support for national liberation struggles and Third World movements all over the globe.

Anti-imperialist Struggle

Che gave his life for the liberation of Latin America, Asia and Africa from the US Empire, in an unparalleled example of internationalism. His solidarity was an unbreakable commitment, which survives his death and by its example unceasingly continues to threaten imperialism. He knew that making the revolution is a grueling and costly ordeal; he chose it unswervingly in the knowledge that the price of submission to imperialism is incomparably greater. A fervently steadfast continuation of this anti-imperialist struggle is the only homage we can give to him on his birth anniversary.

Yanis Iqbal is an independent researcher and freelance writer based in Aligarh, India and can be contacted at [email protected]

GET COUNTERCURRENTS DAILY NEWSLETTER STRAIGHT TO YOUR INBOX