In April 2021, the World Health Organization (WHO) released an annual report, perhaps overlooked in the midst of the raging COVID pandemic, again warning that little recent progress has been made in developing new, desperately need antibiotics. In fact, the report analyzed 43 antibiotics currently in the development pipeline and found that exactly none of them addressed the 13 most dangerous resistant superbugs the WHO has identified, such as carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (carbapenems are the last resort antibiotics). The report also noted that of the 11 antibiotics approved since 2017, only two represent a novel class. The rest were simply derivatives of already existing antibiotics- meaning resistance to those derivatives could come quick, rendering them less effective.

Antibiotic resistant bacteria is already a huge problem that will only grow exponentially worse without a new, effective class of antibiotics. At least 700,000 people die of antibiotic-resistant infections every year. For the U.S., according to The Center for Disease Control and Prevention, every year more than 2.8 million antibiotic resistant infections occur, with more than 35,000 deaths. A 2019 joint report by the UN, WHO, and World Organization for animal health stated drug resistant diseases could cause 10 million deaths a year by 2050. A recent study published in The Lancet actually tallied 1.2 million deaths from infection in 2019. That is more than deaths caused by malaria or HIV. Of course, this wave hits the poorest people hardest. The Lancet study found deaths caused by antibiotic resistance to be highest in sub-Saharan Africa, 24 deaths per 100,000 population compared to an average fatality rate of 13 per 100,000 in high-income countries.

With the current stock of antibiotics losing effectiveness, and much of it being pumped into treating and growing livestock granting resistant bacteria greater reservoirs to bloom, why isn’t more research and development of new antibiotics an urgent priority? It really is bacteria’s world, we are all just living in it. The answer is actually simple and a perfect encapsulation of the absurdity of the system governing our species: it is not profitable.

Research for antibiotics is costly and difficult, often with the same molecules being rediscovered over and over. Plus the point of antibiotics is to use them for short periods of time, and they work best when fewer people use them. Therefore Big Pharma left the field decades ago to focus on more profitable therapeutics, i.e. drugs that can be taken every day such as statins and antidepressants. In January 2020, the Wall Street Journal quoted Patrick Hudson, a general partner at venture capital firm Frazer Healthcare Partners (a firm with antibiotic investments) that to be commercially successful, a new antibiotic would need to make $300 million a year at peak, far more than usual. This compared to the typical $1 billion-plus sales that get a new drug labeled a ‘blockbuster’ by the industry. While the U.S. government has paid some notice, providing more than $1 billion to support drug development since 2010, and even after some of the requisite corporate acquisitions, more than 90 percent of antibiotic development is happening at small companies. Such companies often have limited capital to get beyond early stage research, and that is before funding sales or marketing.

Artificial Intelligence has recently provided some hope. In a genuine breakthrough, the first antibiotic discovered by artificial intelligence took place in a MIT lab in February 2020. Training an artificial neural network, a machine learning system that can analyze relationships in a data set, with a collection of a couple of thousand molecules, the researchers identified a powerful new antibiotic compound. The computer model, which doesn’t have to be programmed with expertise in molecular biology rather it can learn patterns that experts may not that be aware of, can screen more than a hundred million chemical compounds in a matter of days. The model is designed to pick out potential antibiotics that kill bacteria using different mechanisms than those of existing drugs. The researchers named the new compound halicin, after the killer AI from 2001: A Space Odyssey. Tests indicate halicin is quite a killer, having success against the WHO’s three biggest superbug targets when tested on mice. In April 2021, researchers at IBM announced similar results with their AI system.

AI can mitigate the issue by making production cheaper but the lack of incentive remains. Indeed, in their study the MIT researchers commented on ‘the decreasing development of new antibiotics in the private sector that has resulted from a lack of economic incentives is exacerbating this already dire problem.’

It is hardly just new antibiotics. The world is witnessing another example where a lack of profitability is causing great damage, namely vaccines. Once the COVID pandemic began, the speed at which vaccines were developed to combat it, around nine months instead of some years, was a marvel of science and planning. Yet it can hardly be said to be a product of the entrepreneurial spirit. Years of basic research conducted by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the Defense Department, and publically funded labs was instrumental. Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna may now have some newly minted billionaires, but they depended on years of publically funded research to develop the mRNA technology. The concept of RNA modification was first developed by scientists at the University of Pennsylvania. Another key element of the vaccines, the lipid nanoparticles, a tiny designed bit of fat that cloaks the RNA to ferry it through the blood into cells before dissolving, thereby allowing the RNA to do its work, was developed at MIT and various other academic labs. There were also the billions of dollars of advanced purchases of the vaccines. The U.S. government promised to purchase $2 billion worth of the Pfizer vaccine and guaranteed Moderna about $2.5 billion for the manufacture of its vaccine.

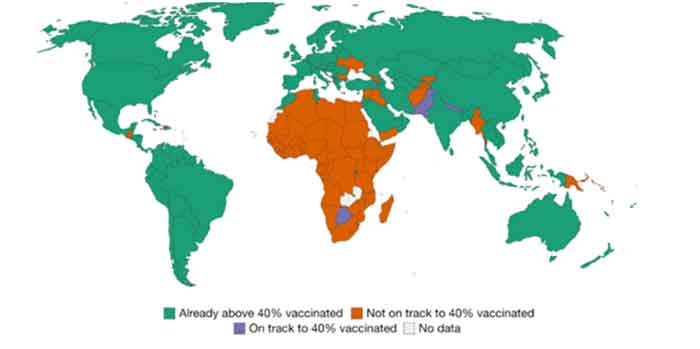

If the development of the vaccines was a triumph for public medicine, their distribution has been the embodiment of capitalism. While high-income countries are receiving third shot boosters to counter the highly contagious Omicron variant, as of the end of 2021 populations in low-income countries have received less than 2 percent of all doses. Covax, the WHO backed effect to provide doses to the poorest countries missed its 2021 goal of distributing 2 billion doses by more than half. Despite an increase in December the program delivered just over 800 million by the end of the year. The program was severely setback last spring when exports were halted from its largest supplier, the Serum Institute in India, to deal with India’s gruesome Delta wave. Other issues that have plagued the program are the shipment (or dumping) of nearly expired doses and lack of distribution capacity. With vaccine manufactures and their governments protecting patents and limiting technology transfer, the WHO’s goal of vaccinating 70 percent of the planet by the middle of this year seems far-fetched.

The Delta variant was first discovered in India, the Omicron variant in South Africa. It is possible that the Omicron variant, more contagious and less deadly than earlier variants, signals COVID’s evolution towards a mild, endemic form. According to one estimate, by October 2021 86.2 percent of American immune systems may have interacted with virus’ protein. But as this is not inevitable and counting on it is playing with fire, especially with much of the world unvaccinated. Meanwhile, according to the People’s Vaccine alliance, as of May 2021 vaccines makers Pfizer, AstraZenaca, and Johnson & Johnson had paid out $26 billion in dividends to stockholders, an amount that would be enough to vaccinate all of Africa.

Faced with such obvious market failure, the solution presents itself: A nationalized pharmaceutical industry fully under public control. Under such a system, money from profitable drugs could simply be channeled to less profitable things like vaccines, antibiotics, and neglected tropical diseases. Such a solution may still seem impossible today but it need not be. Some countries already have nationalized health systems. In the past decade, support for universal healthcare has increased in the U.S. If the COVID pandemic continues to spawn new variants the contradictions of the pharmaceutical industry will only become for apparent. The leap to incorporate drug developed into a universal healthcare system wouldn’t be a huge one. And as the potential crisis of antibiotics gets worse, such a solution will be more obvious, it will be necessary.

Joseph Grosso is a Writer and librarian in New York. (He is the author of Emerald City: How Capital Transformed New York. : Emerald City: How Capital Transformed New York: Grosso, Joseph: 9781789045369: Amazon.com: Books)