by Dr Anupam Bhandari & Tristan Partridge

Introduction

The Chipko Movement is one of the most well-known popular movements in India, if not the world, and is frequently cited as an influence on subsequent activist groups – marking something of an environmental revolution in India. At root, it was the movement for saving trees in the Himalayan regions of Uttarakhand. Its influence stems in part from its members’ adherence to Gandhian practice and methods of non-violent resistance – taking direct action by hugging trees in order to protect them from being felled.

Such a well-known movement has subsequently been documented in the literature in some detail, particularly detailing movement practices, horizontal modes of organizing, and the fact that it was a powerful women’s movement. Some accounts query the extent to which the Chipko Movement was ‘leaderless’: “while women were the main actors involved in Chipko, the protests were nevertheless primarily associated with the actions of two men, Chandhi Prasad Bhatt and Sunderlal Bahuguna” (Hannam 1997, p. 59); “at times, actions were spontaneous, and at times undertaken by women, but it seems even at the height of Chipko activity the “leaderless” Chipko movement was to a large degree led by Bhatt and the DGSS workers, Bahuguna, Dhum Singh Negi and others” (Weber 1987, p. 626). In the present work, and drawing on original source material, we discuss the contributions of two such leaders who have typically received less attention in the documentary accounts of Chipko. One is Dhoom Singh Negi, previously mentioned, and the other is Kunwar Prasoon. While our emphasis is always on the teamwork of ordinary people in local villages – the mainstay of the Chipko Movement – here we add to these accounts and describe some of the actions of two other unsung heroes in the success of the Chipko Movement. Our overall goal is to look in more detail at what became a central tenet of the Chipko Movement: the idea that ecology is the permanent economy.

Early days and mobilizing slogans

There are various accounts in the public domain regarding how the Chipko Movement originally began, though many overlook some significant preceding incidents. For instance, in 1968, Sunder Lal Bahuguna, Sarvoday leader, wrote a book about the development of hills and forest policy for the Garhwal Himalayan region of Uttarakhand. The book is focused on how people in the Garhwal Himalayan region might gain employment based in the use of, and care of, the forest. The question of forest-related employment gained less attention from 1969 to 1971, when Sarvoday activists were deeply involved in the anti-liquor movement in Uttarakhand. During that same time, some Sarvoday activists had established factories for processing pine gum and had acquired wood-cutting saw machines.

This was a time when the Forest Department had allotted to these groups very few areas of forest for cutting; the majority of trees designated for cutting had been allotted to commercial contractors from outside the region. In response to this unequal allotment of trees, Sarvoday activists became discontented with Forest Department and organized the first march against forest policies which took place on 11 December 1972 at Purola in Uttarkashi district of the Garhwal Himalayan region. A further protest against forest policy was then planned for Chamoli district of Garhwal Himalaya. In the morning of 13 December 1972, Sarvoday activists Ghanshyam Shailani, Sunder Lal Bahuguna and Chandi Prasad Bhatt took a taxi on rent, moving from Uttarkashi to go to Gopeshwar in Chamoli district. However, due to the large distances involved, they were unable to reach their destination in time; they spent the night in Rudraprayag at the office of the Khadi Commission.

The night of 13 December 1972 was to become very important in the history of the Chipko Movement. One of the Sarvoday activists, Ghanshyam Shailani, a renowned poet of the Garhwali Language, wrote a poem with the title, “Chipko.” This poem had a strong message in the local language: that we need to save our trees since they are the basis of all our wealth. It is a poem that both contains the core beliefs, and helped initiate, the movement that became the Chipko Movement.

Moreover, on 15 December 1972, Sarvoday activists started a protest march calling for a revised forest policy. Ghanshyam Shailani was leading the march, beating a drum and singing the Chipko poem he had written. He helped inspire people to hug the trees as a mode of defense. Though many participants consider Ghanshyam Shailani “the voice of the Chipko Movement,” his contributions have received less attention than many claims they deserve. His Chipko poem had given not only the name of the movement but also helped clarify the direction of the movement. The poem says, “don’t make any violence, just hug the trees and save them from cutting.” This added new dimensions to a movement that had started in several regions of Uttarakhand, a movement which from 1972 to 1977 was primarily an economic movement focused on ensuring trees would be allotted to local people (and not to commercial contractors), rather than a movement that sought to prevent destructive deforestation and sought more harmonious relations with forests themselves.

Figure 1: Picture of Kunwar Prasoon

It was in 1977 when slogans written by Kunwar Prasoon ushered in a transformation in the direction of the movement – from a primarily economic movement to an avowedly ecological movement. One of Kunwar Prasoon’s famous slogans in Hindi is:

Kya hain jungle ke upkaar, mitti, pani aur bayar;

Mitti pani aur bayar, jinda rahne ke adhar.

What are the blessings of a forest?

Soil, water and air;

Soil, water and air,

The very foundations of life.

See uphill wherever mining

Downhill the farms, a desert

Fields ours, seeds yours

Will not do, will not do

Of Kunwar Prasoon’s many slogans within the Chipko movement, this is perhaps the most well-known. Other slogans called people to embrace non-violence and to hug trees to save them from cutting. Together, these slogans inspired both Sarvoday activists and village residents to participate in and dedicate themselves to the ecological Chipko movement. The core message here, and the central idea of the ecological movement that the current article seeks to emphasize, is that ecology is the permanent economy.

The Ecological Chipko movement: background

The transformation in the direction of the movement – from an economic to an ecological focus – coincided with the Chipko message being adopted and developed in the Henvalghati region of Tehri District. In other places, forest-related activism had focused on attempts to secure forest-related employment for local people, calling for policies that would ensure trees for cutting would be allocated to locally-based firms and groups, not to outside contractors. The transformation in the movement, begin in 1977, took place largely under the guidance of Dhum Singh Negi, Kunwar Prasoon, Vijay Jardhari and Pratap Shikhar.

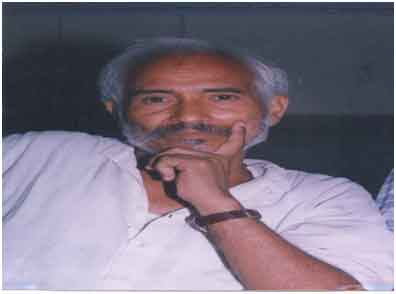

Figure2: Kunwar Prasoon addressing a meeting during Chipko Movement in Advani forest in Henwalghati, Garhwal Himalaya Regions

On 30 May 1977, a foot march was undertaken from Jajal (in Tehri Garhwal District) to Gotars forest. As participants reached the forest, they undertook actions to care for the trees there: removing tin from the trees that had been placed there to collect pine gum; putting soil on the exposed areas or ‘wounds’ on the trees; in some cases placing cloths around these areas as a kind of bandage for the trees. These actions had been repeated in Bharadi forest on 25 July 1977, and similar acts were undertaken also in Jodidanda forest.

After hearing of these localized initiatives, the District Forest Officer visited Gotars forest for an inspection. He found that in Region Number 47, there were thousands of such wounds on the trees for harvesting pine gum and that the length and breadth of these incisions/wounds were larger than standard allowable parameters. In response, the District Forest Officer immediately suspended the local Forest Ranger and canceled the agreement that was in place with the contractor. That contract had been signed for eight years; this move canceled it after four years. District Forest Officers then stopped the work of pine gum harvesting not only in Gotars, but also in Bharadi and Jodidanda forests.

The auction of forests in Tehri Garhwal district had been scheduled to take place on 13 October 1977 in Narendranagar town hall. Henvalghati activists Dhum Singh Negi, Kunwar Prasoon, Pratap Shikhar and Dayal Singh Bhandari attended and raised their concerns before Devi Prasad Gupta, the local District Forest Officer. The activists pointed out that the forests of Henvalghati are found across very steep-sided valleys, and deforestation thus greatly increases the risks of flooding and landslides. They further argued that removing the green cover from Henvalghati would affect local hydrological processes and would make the flow of the River Henval unstable. They also opposed the auctioning off of the forest since it would negatively impact the availability of grazing for cattle and of timber and firewood collected by local residents.

However, the District Forest Officer did not accept the activists’ demands and the forest auction went ahead. A bidding process for auctions of Advani and Salet forests also took place. During that time, in the auction hall, activists gathered and declared, “We, the people of Henvalghati, want to address the contractors: please don’t participate in the bid. Otherwise, we will start a Chipko movement for saving our trees.” These were the words of Kunwar Prasoon, and they were enough to dissuade contractors from participating in the auction of the Henvalghati forests. Yet while some auctions were stalled, other areas were allocated to contractors. In response, a few days later on 18 October 1977, Dhum Singh Negi, Kunwar Prasoon, Dayal Singh and Pratap Shikhar called a public meeting where it was decided that the Chipko movement would gather to defend the forests that were being auctioned off. It was also decided that a request to stop the auctioning of Henvalghati forests would be sent to the Chief Minister and Forest Minister of what was then the state offices concerned, Uttar Pradesh. The government, however, was not ready to change forest policy.

After 40 days, the contractors received an order from the government for tree cutting, with the full assistance of the Forest Department. A Forest Department representative also spread the rumor among local residents that if they were to participate in the Chipko movement, they would be banned from entering the forest to collect grass and firewood, as they were accustomed to doing – perhaps also that they would face a police response and would risk jail time. These rumors did nothing to affect the vision of Kunwar Prasoon, Dhum Singh Negi, Dayal Singh, Pratap Shekhar, Vijay Jardhari, and the local people of Henvalghati; they were determined to save the trees using non-violent methods. In the Advani forest, a contractor said to the people, “don’t hug the trees, otherwise I will have to cut you as well.” Activists maintained their practice of non-violence, these events occurring on 8 December 1977. The women of Advani village also requested that Dhum Singh Negi, who had been on hunger strike since 4 December 1977, end his fast. On these requests of local women, Kunwar Prasoon, and Dayal Singh, Mr. Negi ended his fast on 8 December 1977.

Further emphasizing the importance of saving trees, on 13 December 1977, the people organized a Bhagwat Katha (Story of Geeta) in the Advani forest. The end of the Bhagwat Katha was on 20 December 1977. On that day, the people took an oath to never again use sapwood nor bring any more wood from the forest than was enough to meet their everyday needs – a resolution to save the trees. On this occasion, three women leaders, Sudesha Devi from Rampur village, Bachani Devi from Advani village, and Saunpa Devi from Berani Village were also present with Dayal Singh Bhandari, Dhum Singh Negi, and Kunwar Prasoon who, at this time, wrote and released a Manifesto for Forest Rights.

Meanwhile, Sahet forest, which is about 15 miles from Advani forest, presented a new front of action within the growing Chipko movement. Contractors at that time were under the impression that the movement was limited only to Advani forest, and in the middle of the night, they sent Kashmiri laborers into the Sahet forest to cut trees. Once the trees were fallen, local people sent word to Chipko activists. Then, on 24 December 1977, a march of people arrived in the Sahet forest with the result that the Kashmiri laborers stopped cutting trees. However, the contractor then lodged a complaint against the Chipko activists. Two days later, on 26 December 1977, police came to Henvalghati, but were unable to find sufficient reason for their arrest; the police left having only given a formal notice to the Chipko activists.

That was not the end of the matter, however. On 2 January 1978, the District Forest Officer of Tehri Garhwal came to the Advani forest to ensure that the cutting of trees would continue. As he reached the Advani forest at noon, he encountered an unexpected vision: the people welcomed him carrying a burning lamp. The idea of showing a burning lamp came from Kunwar Prasoon; it was a gesture of non-violence against the District Forest Officer. The burning lamp was a symbol to both recognize their demands and to prevent the Forest Department from moving towards darkness. As the District Forest Officer entered the forest, the gathered activists and residents also chanted the inspirational Chipko movement slogans that Kunwar Prasoon had written.

Slogans were to become a critical strength of the Chipko movement. They inspired local people, village women and other participants and encouraged them to get involved. Hearing the slogans of the Chipko movement, the District Forest Officer was at a loss, asking ‘why are you using burning lamp in the day?’ Kunwar Prasoon answered that the burning lamp was for showing a clear path to the Forest Department, who seemed to misunderstand the motivations of the Chipko movement – about empowering our nature, empowering ecological systems, empowering local people, and also empowering the Forest Department. On that day, a public meeting was held in the Advani forest under the supervision of Smt. Bachani Devi, another unsung hero of the Chipko movement who challenged the Forest Department and its representatives. In the public meeting, participants came of all ages, including Jagtamba Prasad (aged 14) and Raghunath Singh (age 80). In their own terms, people described their everyday relations of interdependence with the forest and links between the forest and their livelihoods – economic aspects of the surrounding ecology as described by villagers themselves.

After the public meeting, the whole scenario had changed. The Regional Forest Officer returned to the forest, and the contractor brought in laborers from Ranipokhri to be deployed in Sahet forest. There, the cutting of trees began. On the third day, people had heard about this, and a march of activists with local people went to the forest, beating drums and chanting Chipko slogans. As the march reached the forest, the contractors and laborers had hidden amid the long forest grasses. A meeting was held in the forest, but there was some confusion since no laborers were to be seen. As a precaution, however, on that day the gathered women decided that they would take on the responsibility of observing the forest since it was they who frequently spent time in the forest gathering fodder grass. The people in the march then returned home, while Dhum Singh Negi and Hukum Singh stayed behind in the forest for observation. The laborers who had been hiding were unaware that Dhum Singh and Hukum Singh had stayed, and so began again their tree cutting work. Suddenly, Dhum Singh emerged and embraced a tree. As he hugged the tree, labors tried to cut down another tree. Dhum Singh then sat down beneath the tree that the laborers were about to cut, and began reading from the Bhagwat Geeta. Seeing this, the laborers felt they were doing wrong. The laborers told to a contractor they could not cut a person; they then left the forest.

The contractor then went to the police and complained that a person hugging a tree was preventing them from tree felling. On 7 January 1978, this story was spread across the region through a Chipko bulletin. Upon hearing this story, a women’s meeting was held at Jajal on 12 January 1978 and Kunwar Prasoon, Dhum Singh Negi and Dayal Singh were invited to attend. The women pledged their support for the movement. During this period, a regional member of the Assembly had also shown his support for the Chipko movement. Despite these gains, however, a new incident at Advani forest raised challenges.

A contractor from Advani village offered higher labor rates for cutting trees in the Advani forest and he recruited three laborers from the village. On 17 January 1978, they went to cut trees. That same day, the police and Forest Department representatives were in Advani, as were the villagers themselves along with activists gathered to participate in the Chipko march. Crucially, Dayal Singh Bhandari, Ramraj Badoni and Jivanad Shriyal were in the forest keeping watch. As the three laborers from the village began cutting trees, Dayal Singh and Ramraj Badoni were hugging trees to protect them, but could not convince Jivanad Shriyal to do so, saying he had not come to be cut by laborers. At that time, Kunwar Prasoon was in the village spreading the message of the Chipko movement through his slogans. By the time a march of the people reached the forest, 12 trees had been felled and 5 more in the process of being cut. The village women told local laborers; don’t show your face to the village people because you have been destroying our forest. Kunwar Singh, who was just 13 at the time, started a fast against his father Jot Singh, demanding a promise from his father that he would never again to the forest for tree cutting.

A few days later, a meeting was called by the Forest Minister in Lucknow and he permitted the cutting of trees for scientific purposes. Again the Forest Department wanted to demolish the Chipko movement. However, on 26 January 1978, the people of Henvalghati following the leadership of Dhum Singh Negi and Kunwar Prasoon celebrated that day as “Adhikar Divas (Rights Day).” The people again organized a march on 28 January 1978. Most of the strategies for the march and for increasing the participation of the people were organized by Kunwar Prasoon.

On 30 January 1978, Chipko activists along with local people were celebrating the martyrdom of Mahatma Gandhi. During that time, news spread among the people that a Provisional Armed Force would be provided to accompany labourers who were cutting trees. On 31 January 1978, that came to pass, and a Provisional Armed Force reached Jajal in two trucks. For the effect of instilling further fear among more people in more villages, the Provisional Armed Force also carried out foot marches in the Henvalghati regions. However, before they reached the Advani forest, the people of Henvalghati gathered there and were chanting the slogan:

Kya hain jungle ke upkaar, mitti, pani aur bayar;

Mitti pani aur bayar, jinda rahne ke adhar

What are the blessings of a forest?

Soil, water and air;

Soil, water and air,

The very foundations of life.

They also sang 3 or 4 other slogans of the Chipko movement also written by Kunwar Prasoon. The Provisional Armed Forces were standing in formation and the City Magistrate of Narendra Nagar was also there. A contractor arrived with 20 Nepali laborers and ordered the labor for tree cutting to begin. Then Kunwar Prasoon, Dayal Singh, Dhoom Singh and other people started hugging the trees. On that day, the contractor had come with some local sweets as a gift or bribe, which he thought would be enough to ensure he could start tree felling. However, the Chipko activists persisted, hugging trees for two and a half hours. Suddenly, the City Magistrate got a message from Lucknow; the Provisional Armed Forces, police, City Magistrate and contractors all left the forest immediately.

On 4 February 1978, a summons had been issued by the City Magistrate to Kunwar Prasoon, Dayal Singh, Dhum Singh Negi and a number of other activists. The notice stated that since the activists started Chipko movement in the forest, the contractor had been unable to cut trees. In court, the activists answered the summons, stating that the movement was non-violent and that there is no possibility of violence within the movement. The movement was full of peace since the leaders Kunwar Prasoon and Dhum Singh Negi were inspired by Gandhian ideology. They always followed non-violence in protest methods. After a few hearings in court, all the cases were withdrawn on 11 April 1979.

Before that, however, on 9 February 1978, there was to be an auction of the forests of Tehri and Uttarkashi in Narendra Nagar at Townhall. Chipko activists decided to prevent the bidding process from going ahead, seeing no other option for saving their trees. On 8 February 1978, under the leadership of Kunwar Prasoon, Dhum Singh Negi and Dayal Singh Bhandari, the people of Henvalghati went to Narendra Nagar through foot march of 30 kilometers. They reached the Town Hall in the evening of 8 February 1978. During the night, the people were shouting Kunwar Prasoon’s slogans of the Chipko Movement and also singing a Chipko Song written by Ghanshyam Shailani.

In the morning, police removed the protesters from the town hall and then they sat in the road. Suddenly during the time of the auction, the protesters opened the door with force and went into the auction hall. As they entered in the hall, they saw the contractors and Forest Department representatives leaving the hall via a back door. Women from the Chipko group occupied the seat of the District Forest Officer and declared that they would stay there until the bidding process had been halted. During the entire day, the Forest Department and police did not make any reaction. However, in the night, the people were informed that 14 men and 9 women had been arrested. The police took them to Tehri Jail. They were in jail for fifteen days and on 23 February 1978 they all were released without stipulation. By that time, the auction of the forest had been done. However, their work for saving trees was, and is, appreciated by the people of Henvalghati.

Dr Anupam Bhandari ,Department of Mathematics, School of Engineering, University of Petroleum & Energy Studies (UPES) Energy Acres Building, Bidholi Dehradun- E-mail: [email protected]

Tristan Partridge, Department of Anthropology, University of California, Santa Barbara