In an incident that raised eyebrows recently, budget airline IndiGo denied boarding to a specially-abled child on a Hyderabad-bound flight at the Ranchi airport. The wheelchair confined boy in his teens apparently posed a safety hazard for the flight because he was in a state of panic. There were doctors on board the flight who felt otherwise and suggested that the airline obtain medical advice from the doctors attached to the airport. The airline staff declined.

A senior official of the Directorate General of Civil Aviation (DGCA) later informed that the aviation safety regulator is probing the incident and that a report had been sought from the airline. Later a fact-finding probe was initiated as the aviation safety regulator was “dissatisfied” with IndiGo’s report on the incident. The probe would look into whether specifically, the applicability of the regulation detailing requirements for the carriage of persons with disability or persons with reduced mobility was followed. ,” The incident was brought to light in a Facebook post by a passenger at the airport who was waiting to board another flight.

About 2.2% of India’s population lives with some kind of physical or mental disability, as per a National Statistics Office report released in 2019 This number is is more than the entire population of Australia. Rural men have the highest prevalence of disability in India, according to the report. A higher proportion of men were disabled in India compared with women, and disability is apparently more prevalent in rural areas than in urban areas. Inability to move without assistance is the most common disability, or possibly the most reported as the most visible form of disability. More men experienced locomotor disability than women.

While the government has expanded the categories of disability to report in the upcoming 2021 census(postponed due to Covid), many families will not report if someone in their household has a disability, and some census takers simply fail to understand and properly report cases of disability and so as in everything else, under-reporting is the norm.

For those with special needs, life is always a daily challenge anyway. To cite another instance of harassment from the airport itself, 4 years the CISF which provided security at most of the busier airports in the country, had dispensed with the requirement for passengers wearing prosthetic limbs to remove them at the security checkpoint. But in October last year, TV actress and classical dancer Sudhaa Chandran was asked to remove her artificial limb at the security check at Mumbai airport. After she raised a protest including a Tweet to the Prime Minister, the CISF had to issue an apology. It is not uncommon to read about passengers talking about humiliating and outdated security checks that often involve stripping off their pants and having to pass their artificial limbs through the X-Ray machine with others’ bags and laptops.

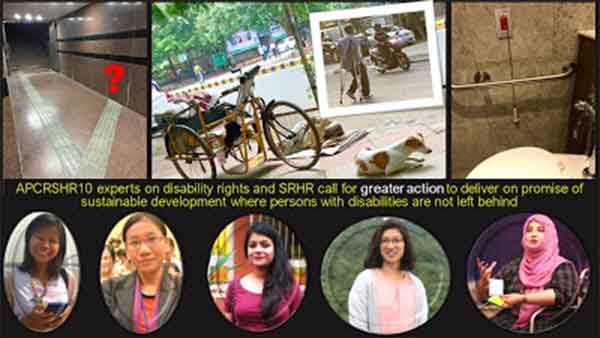

In Delhi where I live, a short walk around virtually anywhere will reveal buildings with only stairs and no ramps or steep, uneven pavements with stalls intruding on their spaces, running alongside unruly traffic. Navigating these crowded streets is hard for anyone, and due to the sheer inconvenience of it all, many individuals with disabilities don’t even try. Disabled friendly facilities are almost never available and if available, are usually poorly maintained. Even a wheelchair user, possibly economically better off is confined to a small space as well—their car. Independent movement beyond the vehicle is limited. Despite vast differences in financial and social capital, the experiences of people with physical disabilities are remarkably similar.

When it comes to accessing public transport, in many cases it may be possible for them to access the Delhi Metro, but it is challenging and frustrating to take buses. Even though the Delhi bus fleet has a large number of low floor buses to accommodate ramps, the bus stops are not planned in a way that those with mobility challenges can get to the bus stop and board a bus. Taxis are not equipped to cater to wheelchair users either. Even in the Delhi Metro, although the station itself may be disabled-friendly, getting in and out of the station is no simple feat.

For those with disabilities who live in rural areas, there are different challenges. For instance, employment opportunities, such as they are are largely situated in the urban areas. To avail of them either has to start living in the city or eventually forced to leave the job due to commuting issues as already pointed out and the paucity of accommodation which they can use and afford. All sorts of quotas are available in the government sector but the numbers actually employed are meagre. Lack of IT services prevents access to information and knowledge and opportunities to participate. Lack of services or problems with service delivery, especially at the last mile also restricts the participation of people with disability.

There are also archaic processes to deal with. In order to gain admission to institutions serving persons with disabilities, or file cases about accessibility with the Office of the Chief Commissioner for Persons with Disabilities, one has to obtain a “Disability Certificate.” In order to legally identify as disabled, the person must be “40 percent disabled”— an ambiguous distinction that is no doubt being interpreted differently across the country. Beyond the social stigma of applying the “disabled” label, the hurdles to obtaining the certificate are steep. A well-resourced person can understand the process and pay doctors’ fees, but still must navigate an inaccessible environment to meet appointments. In many areas, the office of the Civil Surgeon or the Chief Medical Officer who is meant to issue the certificates, itself may not be disabled-friendly.

Internationally, several cities organise Disability Pride parades which centre around Persons with Disabilities showing off their disabilities. There exists a section of people who feel that disability is nothing to be proud of, just as it is nothing to be ashamed about – it’s just something that happened. However, the flaunting of something that people otherwise see as weak, damaged, or oppressed could be an incredibly powerful reclaiming and may need to be done. The Pride parades are largely associated at the present moment with the Gay Parades in many cities including India, which have enabled gay people to come out of their closets, become visible, and be numbered. Over time, has led to a small measure of social acceptance for them. Will it work in other contexts? One needs to test and see.

Meanwhile, I must say though that though I write about disability issues now and then as something that bothers me, it is from a safe space. Venturing outside my echo chamber into the more uncomfortable outside world and being equally vocal about it there is a challenge that I myself need to undertake.

Dr Shantanu Dutta , a former Air Force doctor is now serving in the NGO sector for the last few decades.