In 1971 , when I left school, I was sure that I was opting out of the traditional Brahmin world–it was too burdensome for a woman to carry that cross. Gita Ramaswamy in her just released Memoirs

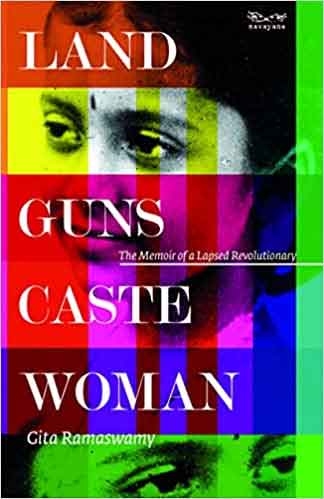

Land, Guns, Caste, Woman (2022)

Gita Ramaswamy was born in a Brahmin family, never remained one in her later life. She is an activist and writer, now has written her memoirs Land, Guns,Caste and Woman (Navayana, 2022). In her memoirs there is an unusual chapter ‘Brahmin at Home, Catholic in School’. This chapter in the book tells how with English medium education in Catholic Christian schools, actually the Brahmin women’s liberation from the most atrocious brahminical anti-woman traditions, practices and torturous life process, have changed. She narrates how in the course of education in a Catholic school in Madras (Chennai) she fought the Brahminic myths and superstitions in the family and caste having been brought up in a middle Government employed father ( in her words patriarch) headed family .

Gita Ramaswamy was born in a Brahmin family, never remained one in her later life. She is an activist and writer, now has written her memoirs Land, Guns,Caste and Woman (Navayana, 2022). In her memoirs there is an unusual chapter ‘Brahmin at Home, Catholic in School’. This chapter in the book tells how with English medium education in Catholic Christian schools, actually the Brahmin women’s liberation from the most atrocious brahminical anti-woman traditions, practices and torturous life process, have changed. She narrates how in the course of education in a Catholic school in Madras (Chennai) she fought the Brahminic myths and superstitions in the family and caste having been brought up in a middle Government employed father ( in her words patriarch) headed family .

Her story tells us that more than the male Brahmin reformers like Rajaram Mohan Roy, Easwar Chandra Vidyasagar in West Bengal, Ranade in Maharashtra, Mahatma Gandhi in Gujarat, Kandukuri Veeresha Lingam Pantulu (in Andhra Pradesh) and so on, it were the Christian English medium schools that liberated Brahmin women from many ritualistic superstitions. In Tamilnadu where Gita studied in formative school days, there was no male Brahmin reformer, at least I know of. However, the male Brahmin reformers only worked against child marriage, female dowry (kanyashulakam), permanent widowhood and so on. In fact in Tamil, coastal Telugu and Kerala regions it was Pariyar’s Dravida Khazagam (DK) movement that pushed Brahmin women into English education because they–men and -women– wanted to live better employed life in the central Government sector all over India and the world as revenge against the anti-Brahmin movement . Some Brahmins women left India in protest against the DK movement and are now living a global life. Kamala Harris’ mother, Indira (much later) Nooyi and many others became big names having come from Tamil Brahmin families.

From Bengal and Maharastra many Brahmin women became English educated in view of the fact that the modern Indian state was seen as a Brahmin asset for best jobs in India and global employment markets, as other castes were nowhere near English education. Pandita Ramabai is a case in point. Now Bengali Brahmin and Kayastha women intellectuals, professionals are all over India and the world. Shudra/Dalit/Adivasi men are nowhere near Dwija women English educated lot. At the same time we do not see Brahmin women sharing agrarian tasks with Shudra/Dalit/Adivasi women in the rural agrarian economy. They are either in the home ritual economy, employment or in politics trying to compete with their own and other caste men.

The Christian English medium schools injected rational thought, new spirit of life completely over growing out of the mythological stories, prarthanas, rituals, home and public bhajans, bharata natyam and so on that were normally making Brahmin girls’ childhood self- sacrificing, male worshipping, grinding themselves them with myriad tasks of ritualism. Gita shows, for the first time in modern Indian history, how English education opened a different world that Sanskrit or Tamil or other regional language education would not have done. There is a lesson for Tamil chaunists in her story, though indirectly.

Before Gita Ramaswamy told her story no other Brahmin highly English educated, westernized, globalized, woman writer, liberal or feminist or free thinking, told this historical facts of Brahmin life. It is a known fact that Brahmins, both men and women, are the most educated in the country today. After the non-priest Brahmins left Sanskrit, English has almost become their modern national and global mobility language. Even the women writers from among them–they are the largest English and regional language writers—-never took a clear stand that English education liberated them by injecting rationalism into their brahminic superstitious miserable home and public life, and that should be made available for all girl children–poor and rich irrespective of caste– in the country. Those who were educated in Catholic Christian missionary schools never said that they did not convert them into Christianity but made rational human beings, with the courage and confidence to live on their own. Gayatri Chakravorthy Spivak, Jhumpa Lahiri, Arundhati Roy (born to Syrian Christian mother and Bengali Brahmin father) , Uma Chakravarti, Kalpana Kannabiran (born in English educated Brahmin family and married a Shudra), Sudha Narayana Murthy, Madhu Kishwar (one does not know what exactly her caste name because she hides it) and many others came from that or similar caste background and became known and influential writers and theoreticians, working in different ideological streams, in different parts of the world. But they never told how Brahmin or Dwija women faced serious superstitions and torturous course of human existence, without knowing what was productive field in their family history and how English, not Sanskrit, that made them what they are today. Some noted women writers with Brahmin family background are second and third generation well educated in English parentage and they might not have faced the same family superstitions and ritualistic fanaticism. Kalpana Kannabiran, whom I know well, is one such writer and took an anti-caste position in her writing. Uma Chakravarti and Arundhati Roy also did that but what is important is writing either through experience or by researching into that cultural heritage would help the nation to come out of Brahmanism. Wandana Sonalkar’s Why I am Not a Hindu Woman and Gita Ramaswamy’s menoir have done that as initiators. Much more needs to be done in future.

More superstitions survive in families that live off others –Shudra, Dalit and Adivasi– labour and when an education of new rationalism liberates them they need to tell honestly what was the root cause of that superstition based atrocity on women. If highly educated in globally communicable language–English– do not write how the schooling in English language liberated them from the caste-cultural oppression of Brahminsm, India as a nation cannot overcome the structural problems that Brahminsm created. Researching about other’s castes (say Dalit and Adivasi) and cultures and backwardness is one thing, but researching about a Brahmin caste, its roots, its good and bad life practices in spite of education in the family and caste is another thing. Those are the families which constructed all kinds of destructive superstitious theories in written texts from ancient days, put them in practice in their families and spread those values in the rest of the society. Research on Brahmin cultural history plays a major role in overcoming oppression on women in India much more than studying about the exploitation and oppression in productive castes. Their women never had Catholic English medium school education that Gita Ramaswamy and most Brahmin women writers had.

Once we agree that Brahmin and other Dwija castes are outside production and in fact are anti-production, then we must see how the women in those castes are controlled by their patriarchal men and how their wives, mothers, sisters and so on were forced to believe that before English education reached their families and how it changed generation after generation with English education. That story needs to be told through their autobiographies and also historical writings. There is no such literature available as of now. Along with Dalit/Adivasi and Shudra female and male autobiographies Brahmin and other Dwija women’s autobiographies would play a major transformation role is proved by Gita Ramaswamy and Wandana Sonalkar through classic work Why I am Not a Hindu Woman.

There is proverb in Telugu, Kadupu chinchukunte kalla meeda padutadi (If one split- opens ones stomach all that is inside falls on ones own feet) Brahmin culture is in every woman’s stomach, but needs to be thrown out,even though it falls on ones own self. This is what exactly progressive Brahmin women writers need to do.

English education started in India only by Christian institutions and later non-Christian English educational institutions came into existence only to do good business. Many of them are trying to inject Brahminic values in their schools. In this situation it is important to know what books Gita read in her school days and how her rebellion against the Brahminic superstitions was because of the rationalist thinking those books injected into her mind. Gita tells “ My earliest memories of resentment for the cross that Brahmin women carried go as far back as when I was ten”.

Brahmin men, leave alone women, were so superstitious that they would not cross seas, by any means of travel. That was when their caste spiritual education strictly limited for men was in Sanskrit language. As per available information the known early Sanskrit educated woman was Pandita Ramabai. But she also later studied English, went to England and became Christian. However, she too never campaigned for English medium education for all children and more girl children. She remained sentimental about Sanskrit even after converting to Christianity and asked for Sanskrit scripted Cross not Latin scripted. She did not ask for an English scripted one, even. Later she wrote a book in English, The High Caste Woman and sold it in America, brought a huge amount of money back and established her institution. She also educated her daughter in English medium Christian school. But see the irony. Savitribai Phule, though not English educated, campaigned for English becoming the mother tongue of all Indians because she thought that it would liberate all the Shudra and Ati-Shudra mothers.

The actual Brahmin women’s liberation seems to have begun with the new practice of Brahmin girls getting sent to Christian English medium schools from the early 1950s onwards by understanding that all Government and private sector jobs were available for Brahmins in Nehruvian India. The Tamil and Bengali Brahmin women families were more conscious of this post-colonial modern desk, teaching, science related jobs were available only to them and they wanted to grab them by four hands–wife and husband. They started sending girls to the best Christian schools and colleges available in big cities.

What exactly Gita said in her memoirs need not be elaborated here as the book is in the market. But just two quotes to show her guts to her family and caste history: “ Our upbringing was contradictory in many regards. While there were traditional strictures in the confines of the home around food, pollution, dress, behaviour codes and culture, there was an equal push towards English language education and a direct encouragement of Western oriented leisure activities, such as seeing English-language films, reading English books or listening to English songs. These were probably seen as helpful to education and career”. This contradictory but transformative Tamil Brahmin women’s life should owe to Periyar’s DK movement, not to Brahmin reformers. Periyar’s movement has done more good to Brahmin women than Dalit/Shudra population of that region. Their love for English language education was a direct result of revenge against Periyar rather than a positive direction derived from the Goddess, Brahmin Saraswati.

Gita talks about many destructive sentiments that Brahminism institutionalized in Brahmin family life and extended them to the rest of the Shudra/Dalit societies for survival without working in the productive fields. Gita’s father was an high end engineer in the Postal and Telegraphs yet he saw to it that the traditional control over women with a rigid regime of superstitious values at home and in caste culture remained in tact. She tells about that regime through many examples of her childhood life.

Gita had four female siblings and no male and all were educated in good English medium schools.

She says “We were six women at home and menstrual periods were three days of seclusion each. Of course, there was no dingy outhouse…But nothing, absolutely nothing was touched while menstruating”. One only must read her book how she rebelled against all of them and became a Naxalite and rebelled against the Naxalite way of living and fighting also. She finally became a Telugu book publisher and liberator of Dalit bonded labour around Hyderabad, and in the process Dalitizing herself to a degree that was possible.

What comes out through this book is that many Dalit women and men, if they love this country and India as nation should write their memoirs and autobiographies what Brahminism or Brahminness has done to them and to the nation. From Arun Shourie to hard core communist Brahmin tried to hide the anti-production, which in essence is anti-national, culture and civilization that they built to keep that caste men and women away from tilling the land and harvesting the crops. By constructing such a spiritual civilization that is destructive to the whole of society they kept the nation in the darkness of scientific experimentations.

I have been asking my Brahmin friends to write about the Brahminness within them, irrespective their ideology or gender. They wrote many autobiographies to say: “my family is of great Sanskrit pundits, and bhajan bhakts”. But nobody wrote how they avoided food production labour in their whole existing history. The Brahmin research scholars, educated abroad and India, that too in English, wrote about others by deploying many borrowed methodologies from the West. They wrote in sophisticated English to deceive the Shudra/Dalit/Adivasi masses. In the process they destroyed the nation as well. They called that knowledge merit.Gita for the first time opened that can of worms.

Kancha Ilaiah Shepherd is a Political Theorist, Social Activist and Author. Many of his books, Why I am Not a Hindu, Post-Hindu India, Buffalo Nationalism, From a Shepherd Boy to An Intellectual– My Memoirs, The Weapon of The Other, God As a Political Philosopher, Untouchable God, The Shudras–Vision For a New Path and so on are meant to reform the socio-spiritual system in India