In the November 1937, an article titled “Rashtrapatiji” was published in a Calcutta-based monthly journal “Modern Review”. Founded by Ramanand Chatterjee in 1907, the journal had good readership among the Indian intelligentsia with a diversity of writers contributing essays, informing or analysing the debates and issues around the country’s freedom movement. The paper “Rashtrapatiji”, written by one Chanankya, drew considerable attention.

Actually, the article came somewhat as a surprise in that its contents were not in any way part of the then larger public discourse or even gossip. At first reading, it caught the readers unawares and seemed almost shocking, if not entirely unwarranted. The author, Chanakya, too wasn’t any known political commentator or writer but his paper did set the tongues wagging.

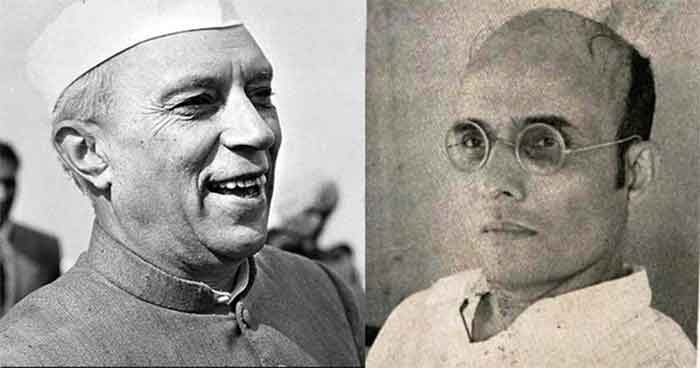

The essay was on Jawaharlal Nehru – and was very critical of him, questioning his personality and aspirations, and the dangers that lie therein for the country and her democracy! It described Nehru as “some triumphant Caesar passing by”, having “all the makings of a dictator in him — vast popularity, a strong will directed to a well-defined purpose, energy, pride, organisational capacity, ability, hardness, and, with all his love of the crowd, an intolerance of others and a certain contempt for the weak and the inefficient.”

It further emphasized, “He might still use the language and slogans of democracy and socialism, but we all know how fascism has fattened on this language and then cast it away as useless lumber.”

Just read these few passages from the essay:

– Rashtrapati Jawaharlal ki Jai. The Rashtrapati looked up as he passed swiftly through the waiting crowds, his hands went up and were joined together in salute, and his pale hard face was lit up by a smile. It was a warm personal smile and the people who saw it responded to it immediately and smiled and cheered in return. The smile passed away and again the face became stern and sad, impassive in the midst of the emotion that it had roused in the multitude. Almost it seemed that the smile and the gesture accompanying it had little reality behind them; they were just tricks of the trade to gain the goodwill of the crowds whose darling he had become. Was it so?

– Watch him again. There is a great procession and tens of thousands of persons surround his car and cheer him in an ecstasy of abandonment. He stands on the seat of the car, balancing himself rather well, straight and seemingly tall, like a god, serene and unmoved by the seething multitude. Suddenly there is that smile again, or even a merry laugh, and the tension seems to break and the crowd laughs with him, not knowing what it is laughing at. He is godlike no longer but a human being claiming kinship and comradeship with the thousands who surround him and the crowd feels happy and friendly and takes him to its heart. But the smile is gone and the pale stern face is there again.

- Is all this natural or the carefully thought out trickery of the public man? Perhaps it is both and long habit has become second nature now. The most effective pose is one in which there seems to be least of posing, and Jawaharlal has learnt well to act without the paint and powder of the actor. With his seeming carelessness and insouciance, he performs on the public stage with consummate artistry. Whither is this going to lead him and the country? What is he aiming at with all his apparent want of aim? What lies behind that mask of his, what desires, what will to power, what insatiate longings?

- These questions would be interesting in any event, for Jawaharlal is a personality which compels interest and attention. But they have a vital significance for us, for he is bound up with the present in India, and probably the future, and he has the power in him to do great good to India or great injury. We must therefore seek answers to these questions.

Ahead, Chanakya writes:

– Jawaharlal cannot become a fascist. And yet he has all the makings of a dictator in him….. His flashes of temper are well known and even when they are controlled, the curling of the lips betrays him. His over-mastering desire to get things done, to sweep away what he dislikes and build anew, will hardly brook for long the slow processes of democracy.

– Therein lies danger for Jawaharlal and for India. For it is not through Caesarism that India will attain freedom, and though she may prosper a little under a benevolent and efficient despotism, she will remain stunted and the day of the emancipation of her people will be delayed.

– He goes to the peasant and the worker, to the zamindar and the capitalist, to the merchant and the peddler, to the Brahmin and the untouchable, to the Muslim, the Sikh, the Christian and the Jew, to all who make up the great variety of Indian life. To all these he speaks in a slightly different language, ever seeking to win them over to his side. With an energy that is astonishing at his age, he has rushed about across this vast land of India, and everywhere he has received the most extraordinary of popular welcomes. From the far north to Cape Comorin he has gone like some triumphant Caesar passing by, leaving a trail of glory and a legend behind him. Is all this for him just a passing fancy which amuses him, or some deep design, or the play of some force which he himself does not know?

– Men like Jawaharlal, with all their capacity for great and good work, are unsafe in democracy. He calls himself a democrat and a socialist, and no doubt he does so in all earnestness, but every psychologist knows that the mind is ultimately a slave to the heart and logic can always be made to fit in with the desires and irrepressible urges of a person. A little twist and Jawaharlal might turn a dictator sweeping aside the paraphernalia of a slow-moving democracy.

– For two consecutive years Jawaharlal has been President of the Congress and in some ways he has made himself so indispensible that there are many who suggest that he should be elected for a third term. But a greater disservice to India and even to Jawaharlal can hardly be done. By electing him a third time we shall exalt one man at the cost of the Congress and make the people think in terms of Caesarism. We shall encourage in Jawaharlal the wrong tendencies and increase his conceit and pride. He will become convinced that only he can bear this burden or tackle India’s problems. He must imagine that he is indispensible, and no man must be allowed to think so. India cannot afford to have him as President of the Congress for a third year in succession….. There is a personal reason also for this. In spite of his brave talk, Jawaharlal is obviously tired and stale and he will progressively deteriorate if he continues as President. He cannot rest, for he who rides a tiger cannot dismount. But we can at least prevent him from going astray and from mental deterioration under too heavy burdens and responsibilities. We have a right to expect good work from him in the future. Let us not spoil that and spoil him by too much adulation and praise. His conceit is already formidable. It must be checked. We want no Caesars….. it is not through Caesarism that India will attain freedom, and though she may prosper a little under a benevolent and efficient despotism, she will remain stunted and the day of the emancipation of her people will be delayed.

Certainly, this came out of the blue.

1937 – the country was still 10 years shy of Independence. Eight years earlier, in December 1929 in Lahore, Nehru was elected the president of the Congress Party. No need to say that it was Gandhiji, far-sighted and master strategist that he was, who elevated Nehru to that position, and ahead of many others much senior. Nehru was only 40 years old then and Gandhiji was convinced that he would attract the much needed, country’s youth to the Congress and the freedom movement. Presiding over the Congress’ historic session in Lahore at the time, Nehru pushed through the demand for Purna Swaraj (total independence) replacing the party’s earlier stance of seeking dominion status for India. This was something which he had long espoused as part of his role in the party’s trade union and other platforms. This demand for outright political independence had led to hectic debates within the Congress and was thoroughly supported by the younger members. After the Namak Satyagrah in 1930, the freedom movement with the Congress at the forefront, gained steam. By 1937, with his youthful, attractive personality, wide social outlook and socialistic bent, learned oratory and energetic organizational skills, Nehru had become widely popular, including among the country’s Muslims, other minorities, the youth and the women. And by then, he had already been imprisoned twice, totalling 539 days.

In 1937, the first general elections were held and though Nehru himself did not contest, he oversaw the Congress national campaign for it, traversing the length and breadth of the country, canvassing for the Congress candidates. The party won an outright majority in the central and most of the provincial legislatures, and amidst the masses, Nehru became the undisputed leader of the Congress, next only to Gandhiji.

So, could this article “Rashtrapatiji” have been written by some jealous, despondent, aspirational individual, who may have desired and possibly considered himself more deserving of being the Congress president than Nehru?

It may also to be considered that Nehru was a single male progeny born into an affluent family, and may very well have been a spoilt child, to which later he actually confessed. Indeed, he was sent to England for schooling and further studies, and later his wide personal travels across Europe and other parts of the world also brought him in political interaction with leaders on issues across the world – all this may also have given him a touch of arrogance. Could it have been that, which may have rubbed some of his Congress colleagues the wrong way?

And then, another question – who was the writer of the essay? As stated earlier, Chanakya was not a known signature. So, could it have been a pseudonym of some Congress-wallah nursing deep grievance and airing his frustration? Or was he just a Congress well-wisher and a patriot, worried about the pitfalls a popular Nehru was likely to fall into? A sort of cautioning Nehru, the rest of the Congress leadership and even the public which was then much in adulation of him?

There was much wondering and guessing.

Another writing

About 11 years earlier, in 1926, a book titled “Life of Barrister Savarkar” was published. The author was Chitragupta. The book was Vinayak Damodar Savarkar’s first biography in English. It describes the activities of Abhinav Bharat (originally formed as “Mitra Mela” in Nasik by Savarkar while still in school) in London and Paris, underlines his leading role in seeking to establish a violent revolution for the independence of India, and states that the organization made “the Indian question a living issue in European and world politics. The Enemies of England all over the world began to take the Indian revolutionaries seriously and opened negotiations with their leaders.”

The biography covered Savarkar’s life up to January 1911, by when he had been sentenced to second Transportation for life, and shifted to India. After hearing the sentence, Chitragupta writes that Savarkar said, “I am prepared to face ungrudgingly the extreme penalty of your laws in the belief that our Motherland can march on an assured if not a speedy triumph”.

Below are some passages from the book,…..

- Savarkar is born hero, he could almost despise those who shirked duty for fear of consequences. If once he rightly or wrongly believed that a certain system of Government was iniquitous, he felt no scruples in devising means to eradicate the evil.

- Vinayak, ever since his childhood, was given to lofty aspirations and marked out by all those who came in contact with him as an exceptionally gifted child…… Amongst his schoolmates he soon came to be known as a scholar and a patriot and a fiery orator who always talked of great deeds and great schemes of India and independence and how he meant to achieve it all and many others things far beyond their comprehension.

- (Prior to his leaving for England to study law.) While still in Bombay, before leaving for England, he conducted a weekly named “Vihari.” So attractive and inspired were his writings that the Vihari rise to a sudden prominence in the rank of Marathi papers and was sold out in thousands even though Savarkar‟s name was not publicly associated with the paper.”

- Savarkar managed to do scholarly work of first class magnitude in writing two voluminous historical works….. No sooner he reached London he began the translation of Mazzini‟s writings in Marathi and within a year of his departure from India had it finished to secure a record sale in Marathi literature. All leading newspapers reviewed ‘Savarkar‟s Mazzini’ in leading articles. Students were made by their teachers, and sons by their fathers, to commit whole passages to memories from the masterly introduction which Mr. Savarkar wrote for the book.

- (Quoting Sawarkar) “Well if I don‟t survive I shall have kept my word, my pledge of striving to free India even unto death and leave a glorious example of martyrdom which in these days of mendacity and cringing political slavery is one thing wanted to fire the blood of my people and to rouse and enthuse them to great deeds. A great martyrdom: some grand example of utter sacrifice and willing suffering: and India is saved. No amount of cowardly tactics in the name of work can whip her back into life. I will risk, will myself pay the highest price…… “

- (Aboard a steamer from Paris to London) “Behold I take this step with a full knowledge that I shall in all probability be arrested one of these days.” “But then?” inquired his companion. “Then I shall try my best to prove to myself that I can suffer as well as work. Up till now I have worked to the utmost of my capacity, now I will suffer to its utmost. For suffering is under our present circumstance bound to be far more fruitful than mere work.”

- Savarkar, when he thus left England in 1910, was nearly 26. He had arrived there when 22 years old. Within the short span of these four years he had transformed the crowed of nerveless ninnies and unprincipled dandies, that the Indian students in England were before generally reputed to be, into band of patriots who, apart from their dreadful methods and questionable tactics, did undoubtedly display a heroic fortitude, a reckless spirit of sacrifice in the interests of their motherland and did indeed win the esteem and enlist the moral sympathy of all European nations in favour of the cause of Indian Freedom.

It might be appropriate to clarify that the grammatical and typographical errors in the passages above, are part of the original text. Unfortunately, these run through the entire book, making it a rather shoddy publication. For a biography, it was wanting in necessary rigour and details. It seemed too hurriedly written and published, and the many grammatical and typographical errors could have been easily addressed and set right with due editorial attention.

Why these two writings are being written about here is they share some strange similarities – and a major difference. First the difference – Chanakya, the writer of the essay in Modern Review is critical of Nehru, is objective and seeks to warn the people of the country on the dangers of idolizing their leader. Savarkar’s biographer Chitragupta, on the other hand, is in complete awe of his subject, influenced by his violent revolutionary spirit. It was in this book, Savarkar was given the sobriquet “Veer”.

Now about the similarities, of which essentially two are being mentioned. The identity of both writers – Chanakya and Chitragupta – was a mystery. Neither of them was a known writer. Both could possibly have been first time writers, for there was no publication prior to these, which these writers could have been credited for. And, more importantly, both don’t seem to have written anything thereafter too.

So, it is possible that both the writings were ghost-authored, and Chanakya and Chitragupta were pseudonyms.

The mystery revealed

It became fairly certain that ghost writers both were. But then who were the original writers of the two works? This is where the second similarity in the two writings lies.

About Chanakya’s essay “Rashtrapatiji”, it was Nehru himself who later revealed – “This article was written by Jawaharlal Nehru, but it was published anonymously (sic) in The Modern Review of Calcutta, November 1937…..” In fact, delighting in this whodunit, Nehru mused that his daughter “Indira was the only person at the time who possibly came close to suspecting that I was the actual writer.”

On Savarkar’s bography, two decades Savarkar’s death n 1987, the Second Edition of “Life of Barrister Savarkar” was released by the Veer Swarkar Prakashan, the official publisher of Savarkar’s writings. In its Preface, it was noted that “Chitragupta” the biographer, was in fact “Veer Savarkar” himself. So the biography was actually an autobiography, written in the third person!

Now, these revelations draw an entirely new set of questions and conclusions – about the individuals under discussion.

“Rashtrapatiji” was possibly Nehru’s attempt to remain firmly tied to the ground realities and not allow the tremendous public adoration he received from getting into his own head. It may also have been his way of reconfirming his commitment to the democratic vision for the country, and of exhorting the countrymen to remain ever vigilant against the dangers of not just dictatorship but also all forms of arrogance and corruption of the polity, down to the district constituent levels. Today, as we face the establishing of exactly those fears, facing severe threats to democracy and the Constitution, Nehru’s words emerge as prophetic, and a re-reading of “Rashtraptiji” today will possibly help us see our own misplaced hopes, gullibility and dangerous acquiescence.

On the other book, Savarkar was arrested in March 1910, for providing the weapon used in the killing of the then District Magistrate of Nasik, in which Abhinav Bharat was implicated. He was taken from England to the Cellular Jail in the Andamans in July 1911. Within a month of his incarceration, Savarkar wrote the first of his four mercy petitions – in August 1911, followed by three more in 1913, 1918 and 1920. He was shifted from the Cellular Jail and shifted to Ratnagiri where he was interred after his release from the jail in 1924. In 1934, he was arrested again in connection to another case, and wrote his fifth mercy petition.

So his first major release from prison had come in 1924 and almost immediately, the writing of “Life of Barrister Savarkar” may have begun and which got published in 1926. The eulogy was, in fact, self-glorification – reflecting arrogance and the hatred of the other!

That then is the tale of two writings. It’s up to us what conclusions we wish to draw from it.

Biju Negi , Hind Swaraj Manch & Beej Bachao Andolan