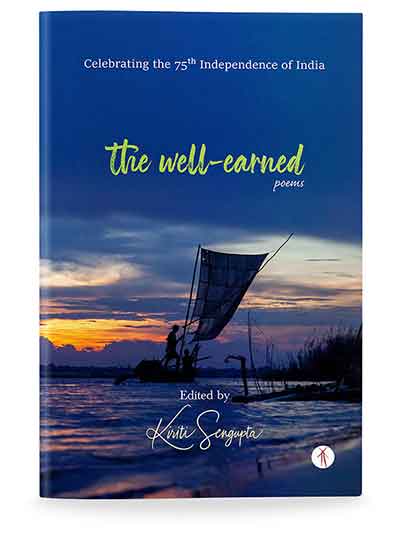

The French theologian Simone Weil wrote, “Attention is the rarest and purest form of generosity.” On the 75th anniversary of India’s independence, Hawakal Publishers released The Well-Earned, a poetry anthology edited by Kiriti Sengupta. This collection sought the nearly impossible: poems defining liberty. Freedom of expression is the artist’s bedrock. However, there seems to be a lack of poetry anthologies celebrating liberty. Sengupta, in anthologizing these poems for the occasion of India’s Independence Day, speaks volumes for the community of poets able to freshly assert their thoughts on our most essential truth of being. As written by the editor in the short introduction, this volume “celebrates autonomy as the key to life.”

However, you will not find poetry on free expression in this anthology as much as you will read poetry that celebrates the deeper purposes of being free. In granting attention to this fundamental aspect of existence, the poets celebrate life itself generously. Many of the poets write of the human responsibility to show care and concern for the weak and enfeebled. There are poems that allude to hunger, deprivation, and spiritual forlornness. Other poems celebrate the beauty of life and offer optimistic perspectives of renaissance and human cheerfulness. Freedom of thought is certainly recognized. We can read through this historically oriented collection the thinking of Indian poets writing in English on a subject essential to human existence. The collection’s title The Well-Earned grants a sense of duty to the subject of liberty. Liberty is not to take for granted, yet the prospect of earning freedom makes it all the more glorious. Wouldn’t this be a fit definition of autonomy?

However, you will not find poetry on free expression in this anthology as much as you will read poetry that celebrates the deeper purposes of being free. In granting attention to this fundamental aspect of existence, the poets celebrate life itself generously. Many of the poets write of the human responsibility to show care and concern for the weak and enfeebled. There are poems that allude to hunger, deprivation, and spiritual forlornness. Other poems celebrate the beauty of life and offer optimistic perspectives of renaissance and human cheerfulness. Freedom of thought is certainly recognized. We can read through this historically oriented collection the thinking of Indian poets writing in English on a subject essential to human existence. The collection’s title The Well-Earned grants a sense of duty to the subject of liberty. Liberty is not to take for granted, yet the prospect of earning freedom makes it all the more glorious. Wouldn’t this be a fit definition of autonomy?

India earned her independence from the British Raj on August 15, 1947. The country was partitioned into Pakistan and India at the time of independence. The poems do not explicitly address political or historical concerns, barring some exceptions such as “Naevus (Birthmark)” by Teji Sethi or “Second Wave” by Mamang Dai. The poetry of this volume rather addresses universal aspects of earning one’s liberty, and many poems embrace the full emancipation of women. Most of the poetry is written in free verse, but there are formal poems such as Nishi Pulugurtha’s haibun “A Song.”

Sengupta further addresses the variety of thoughts on liberty, “The perception of freedom varies—recognition of autonomy enjoys a broad spectrum in human psychology.” The volume is introduced as containing deeply personal thoughts with political and social implications. Nikita Parik writes in “Apocalypse” that the city “holds promises, / but all in future tense.” This implies freedom is yet to be according to the poet. The context of the poem is a sense of waiting for the pandemic to end. In “My Freedom,” Gopal Lahiri writes, “Sometimes freedom just hits me this way, / forcing me to leave my much-maligned body and fly away.” Lahiri’s poem suggests that freedom is something insubstantial, perhaps spiritual in nature. Perhaps it is a concept we are not in full capacity to understand. Freedom becomes something more temporal in Mani Rao’s poem “Classic” in which she writes, “I don’t want anything forever.” The poet reminds us that eternity is a kind of slavery since one cannot leave it, thus flux is liberating.

Jagari Mukherjee’s poem “Strings” speaks of daily human habits with sensuality and sophistication. In this poem, a summer day winds down as “clothes slough off for the day— / drying on the strings of my body, a violin / you play to emulate Vivaldi’s Storm.” The most striking aspect of these lines is the way they bridge the ethereal with the commonplace. The female form becomes a violin, implying life contains a distant music perhaps only poets perceive. “Dreams hang on strings, each / a dyed pearl bejeweling the blue air,” writes Mukherjee. This line shifts the meaning of “strings” reminding the reader of language’s flexibility and freedom.

Sudeep Sen’s “Pankha Pattachitra” alludes to the “unpredictability / of climate change.” This poem reflects habitat in phrases such as “hands [of palm leaves] in slow-motion / calibrating power / of a nascent breeze” which are paralleled by the lines “taking me back / to childhood memories, / of innocence, / of fair weather — / and the spare simplicity / of pure clean air.” The poet relaxes contentedly with his memories before climate change was a prominent issue while remaining conscious of the responsibility the “unforgiving” problem entails.

Each poem is written from a fresh perspective. It seems autonomy is an elusive concept that has qualities we all can identify. Autonomy implies consequence, duty, and independence. These aspects of freedom bring us ambiguous joy and dread. The back cover description reminds readers, “The Sisyphean angst shapes the daily passivity we cling closely to.”

Sanhita Sinha writes in “Khamili Tripura” that “Khamili Tripura does not know about globalisation or demonetization.” This statement is further defined with the following lines, “She understands the farmers are fighters who bring freedom / from hunger—from pain.” The poem suggests that freedom can also be the absence of something—in this case, pain and hunger—rather than presence or addition of something. It also reminds us how near to our being freedom is. Mamang Dai writes in “Lockdown”:

“We’ll carry the old and injured,

Lift up the children, lift them up high,

When the road finds us again,

Calling us to vital things—“

These lines further establish freedom from pain and deprivation, as well as highlight that the preservation of autonomy paves the way for future generations. The feeble are carried on the shoulders of the strong and able during the Covid-19 lockdowns; as the poet writes, we are called “to vital things.” The lockdown paradoxically reminds us of the importance of autonomy. In “Wishes for a Child I Never Had,” Sanjeev Sethi hopes the child not “be vulnerable to whims of another.” Autonomy requires strength of character. Sethi further writes, “May luck and its luster broaden your borders.” These lines imply the necessity of a refreshing global consciousness; indeed, personal autonomy does not withhold social responsibility.

In celebrating India’s 75th Independence Day through an anthology uniting a variety of poets, some as established as Sanjeev Sethi, Sudeep Sen, Mamang Dai, and veteran poet and scholar K. Satchidanandan, the editor declares autonomy as something of inconstant definition. In his own poem Sengupta writes, “Can names lead me / to the anonymous?” This implies that freedom is not something with a fixed form. How can we define it using language itself? Pragya Bajpai seemingly concurs, writing, “I’m yet to awaken, to seek knowledge, / to think the unthought”. Freedom is simply in being, but what is being and how do we achieve it? Is it something we add to the spirit of life, or is it granted by life itself? Bajpai’s poem suggests it is possible to introduce new thought, but the poet also says she is yet to achieve such. Is freedom something yet to be attained?

The Well-Earned reminds us that we must struggle to achieve and preserve liberty. Sometimes this liberty is freedom and space in one’s mind, and other times it is attentiveness to others to rid them of pain and discomfort. Sengupta’s volume redeems the wide-ranging necessity of discussion of our most vital imperatives on the occasion of India’s Independence.

Dustin Pickering is a poet, critic and editor based in Houston, Texas.