Elections to Himachal Pradesh Assembly may be viewed as a symbolic example of what Indian political system and its socio-democratic fibre seem to be heading for. Given the importance accorded by certain leading politicians to try propagate use of religious cards at various levels in several parts of country, one is tempted to deliberate on their relevance in Himachal Pradesh. Here Hindus are more than 95% of state’s population, Muslims around two percentage, Sikhs-1.16%, Buddhists- 1.15% and Christians, Jains and others – each are less than a percentage. Clearly, this is just a mild pointer to actual electoral relevance of Hindu card in practically all parts of country. Of course, the percentage of these communities varies in different parts. Nevertheless, what cannot be ignored is the accelerating pace with which caste-cards are being played politically at various levels. Sadly, their prime purpose appears to ensure electoral victory. If they actually played the role of helping Scheduled Castes (SC), Scheduled Tribes (ST) and other similar sections gain socio-economic benefits they appear deprived of, the situation may have been different.

Himachal Pradesh Assembly Elections have probably once again witnessed electoral battle not just between political parties but more significantly split along caste-lines. The state has the second highest percentage population of Dalits- 27%, with Punjab having the highest. Interestingly, division among Dalits- politically as well as socially- stands out markedly not just in Himachal Pradesh but across the country. This probably is one of the reasons as to why Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP) led by Mayawati has failed to mark its presence prominently outside Uttar Pradesh (UP). If Dalits voted en-bloc, their political strength would not have rested largely on rhetoric, claims and empty promises made by parties dominated by upper-caste politicians.

In addition, it would be erroneous to assume that any group- religious, caste, regional and/or marked by any other ethnic identity- votes en-bloc for any party and/or leader. If this was the case, India would not have witnessed increase in number of parties as well as leaders across the country. This trait is visible in Himachal Pradesh also. Aam Aadmi Party (AAP), formed in 2012, having marked its entry on the state’s electoral field for the first time is hopeful of tasting success here just as it has in Punjab Assembly elections held earlier this year. Besides, a recently formed Rashtriya Devbhumi Party (RDP) has contested from 29 seats. The battle for 68 seats is between 412 candidates with those from Bharatiya Janata Paty (BJP) and Congress trying their luck on all seats and AAP – 67. While BSP has fielded candidates for 53 seats, Left front-11, there are 99 Independent candidates in addition to smaller parties battling for around a dozen seats.

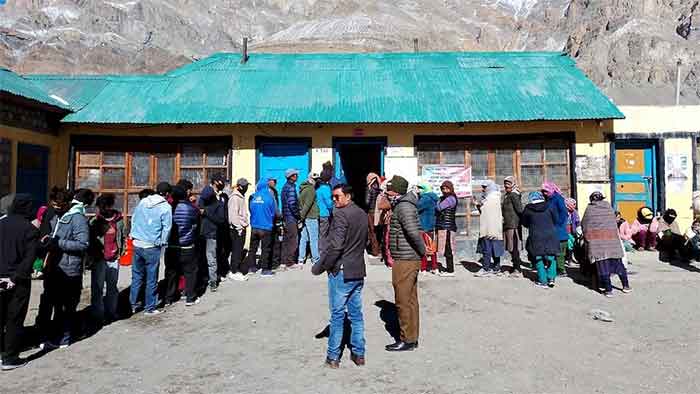

Till the preceding elections held in 2017, the political battle was largely between the BJP and Congress party. Interestingly, over the past three decades, Himachal Pradesh has seen an alternate party in command after each assembly election. As for instance, 2003 elections were won by Congress, 2007 by BJP, 2012 by Congress and 2017 by BJP. If BJP is hopeful of reversing this trend, Congress hopes to return and AAP wants to win. Within less than a fortnight, their political success/failure will be decided with counting of votes on December 8. But this is likely to be just a prelude to what country’s politics seems headed for. Prospects of electoral fates becoming more strongly dependent on caste-factors is probably one of these. Of course, Indian politics has never been devoid of this scenario but recent history witnessed use of religious cards with communal stamp more prominently, particularly in Hindi belt.

The preceding point about caste-factor’s role in Hindi belt is marked by emergence of parties such as Samajwadi Party (SP), BSP, Rashtriya Janata Dal (RJD), Janata Dal-United (JD-U) and so forth in UP and Bihar. These parties have been specifically mentioned as religious card marked by Hindutva-frenzy has been partly responsible for restricting their rise in their respective regional areas. “Secular” label tagged with these parties rests primarily on their being supported by Muslims against saffron brigade.

Against caste-factor, religious-cards have practically no or minimal relevance in Himachal Pradesh. As is well-known, irrespective of whether BJP or Congress heads the government here, it has been dominated by upper caste Hindus. Socially too, bias against Dalits has not ceased to prevail here just as it exists in other parts of the country. True, 20 constituencies are reserved in Himachal Pradesh Assembly, 17 for SC and three for ST candidates. In the outgoing assembly, 15 of these are held by BJP members and five by Congress. Efforts made by BSP succeeded in securing it a single seat in 2007 and none after that. Its share of votes has also declined, from 7.26% in 2007 to 1.7% in 2012 and 0.5% in 2017. Chances of it facing reversal of political fortune in these polls seem dim with more parties in the fray. This also is perhaps a mild indicator of strategies being exercised by rival parties to probably ensure increase of their hold in SC and ST domains and marginalise role of parties and leaders actually claiming to be key representatives of these castes. In a nutshell, this also spells division in their vote-banks and continuance of political domination of upper castes.

It is to be watched as to what degree BSP succeeds in its mission to emerge as the third alternative in Himachal Pradesh. Or whether its hopes are dashed by more parties entering the electoral fray, particularly AAP.

In 2017 elections, against 44 seats won by BJP, Congress won 21, Independents-2 and CPI (M)-1. Political scenario appears to be more complicated this time than before. Notwithstanding the headlines projecting significance of caste-factor playing a strong role in these elections, the underlying fact seems to have been side-lined: — that of this least likely to spell better socio-economic life for deprived sections, particularly castes. Democratically, they may not see better times in the coming years. This may mark weakening of country’s democratic strength, with only nominal relevance being accorded to basic constitutional ideals laying stress on equality of all and so forth. It wouldn’t be surprising if caste-factor displays similar political battle in other parts of country, particularly Hindi belt. Exercise of political strategies laying stress on castes with increasing fervour may reduce frenzy of those banking upon using religious cards stamped with communalism. Himachal Pradesh Assembly results may probably be a trailer to what Indian politics are headed for!

Nilofar Suhrawardy is a senior journalist and writer with specialization in communication studies and nuclear diplomacy. She has come out with several books. These include:– Modi’s Victory, A Lesson for the Congress…? (2019); Arab Spring, Not Just a Mirage! (2019), Image and Substance, Modi’s First Year in Office (2015) and Ayodhya Without the Communal Stamp, In the Name of Indian Secularism (2006).