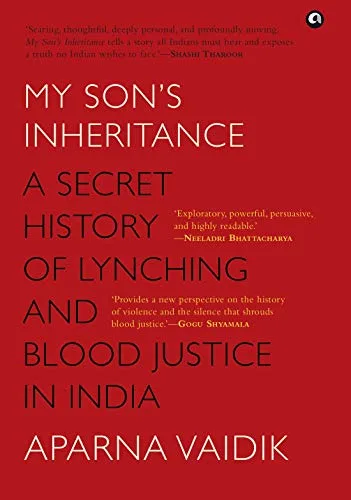

My Son’s Inheritance: A Secret History of Lynching and Blood Justice in India, Aparna Vaidik, Aleph Book Company, New Delhi, 2020. ISBN-13:978-8194233787, Pages 192, Rs 499.

This short book of creative non-fiction by historian Aparna Vaidik collides forcefully and head-on with many of the convictions of the communally-charged political parties in India. Composed in a controlled way, My Son’s Inheritance, is a book that is multi-layered. It can be read as a casual work on the recent histories of cow protection in India, or can be read as an interesting prelude to the mobbing activities of gau-rakshaks and the politics behind it, or as a sturdy treatise on the misplaced notion of the idea of non-violence in India. Vaidik writes this book addressing her son, whom she calls Babu. She wants Babu to grasp the ideas that are floated across the nation, like the mythical philosophies of forbearance and tradition. She wants Babu to locate the mistaken doctrines behind the fiercely passionate acts of societal violence in India. She wants Babu to agree that minorities are mediocre people. She speaks with such kindness and warmth to Babu, and does not sound overbearing when talking about ideologies.

It is generally understood that history can be synthetic. Besides movies, one other important place where history is factory-made is history textbooks. Young people, who are susceptible to accepted notions, get fed on incomplete or piecemeal aspects of Indian history. For instance, Vaidik, in the Prologue, addresses Babu: “You may not know this, or maybe you do, the essence of Indian civilization is also violence. Hinsa bhi tumhari dharohar hai. Violence is also India’s heritage that has been bequeathed from generation to generation. The history of tolerance is also one of tolerance towards violence”. Writing about a lesser known flow of thoughts related to the history of violence in India, the author narrates her own experience of getting exposed to aspects of cow protection, denunciation of Muslims / Dalits, Vedic religion, and religious conversion. As a very short book, there are no detailed discussions on the above aspects. That was not the intention in the first place, it seems. The objective of the author was to throw open questions, with a view to make readers try and find answers for them. Through the hear-say stories of region-specific God-like characters like Bharmall, who challenged a local Muslim butcher to stop taking cows to the slaughter-house. Bharmall, who was a wealthy landlord, said that he would immolate himself if the cows were not released. The story goes that he had to engage in sata (a masculine form of sati) as the cows were taken away for butchery. This story, as narrated by the author, happened a few centuries ago, in the state of Rajasthan. In keeping with the tradition of the place and people, a small shrine was erected honouring Bharmall, the warrior. The cult of Bharmall has assumed a bigger proportion. Protecting cows has become a sacred duty of late.

It is generally understood that history can be synthetic. Besides movies, one other important place where history is factory-made is history textbooks. Young people, who are susceptible to accepted notions, get fed on incomplete or piecemeal aspects of Indian history. For instance, Vaidik, in the Prologue, addresses Babu: “You may not know this, or maybe you do, the essence of Indian civilization is also violence. Hinsa bhi tumhari dharohar hai. Violence is also India’s heritage that has been bequeathed from generation to generation. The history of tolerance is also one of tolerance towards violence”. Writing about a lesser known flow of thoughts related to the history of violence in India, the author narrates her own experience of getting exposed to aspects of cow protection, denunciation of Muslims / Dalits, Vedic religion, and religious conversion. As a very short book, there are no detailed discussions on the above aspects. That was not the intention in the first place, it seems. The objective of the author was to throw open questions, with a view to make readers try and find answers for them. Through the hear-say stories of region-specific God-like characters like Bharmall, who challenged a local Muslim butcher to stop taking cows to the slaughter-house. Bharmall, who was a wealthy landlord, said that he would immolate himself if the cows were not released. The story goes that he had to engage in sata (a masculine form of sati) as the cows were taken away for butchery. This story, as narrated by the author, happened a few centuries ago, in the state of Rajasthan. In keeping with the tradition of the place and people, a small shrine was erected honouring Bharmall, the warrior. The cult of Bharmall has assumed a bigger proportion. Protecting cows has become a sacred duty of late.

However, Bharmall alone is not responsible single-handedly for the perpetration of violence in the name of bovine defence. There were a variety of such stories that have made rounds, inculcating the religion-authorised violent acts of safeguarding cows. The author also documents the efforts of Arya Samaj in raising the awareness levels of the need to protect cows. Soon, cattle-protection assumed a hallowed proportion. And, as can be noticed in recent years, the cows have been sacralised. Those who disrespect cows, by either killing it (butchers), or eating its flesh (beef-eaters), would be severely dealt with (lynched) by the cow protection squads. Obviously, the arrow of hatred is aimed at the minorities in India.

The linkage between minorities in India and electoral politics cannot be divorced from unrest, as Vaidik promptly points out: “The announcement of elections in October 1989 had been preceded and followed by a series of communal riots in north, central and western India, especially in states where the Congress (I), the ruling party, was in power. The leader of the Congress, Rajiv Gandhi, had announced early elections to combat the growing strength of the opposition led at the time by Vishwanath Pratap Singh. Rajiv had followed in the footsteps of his mother, Indira Gandhi, the president of the Congress (I), who had risen to power in the 1970s by appeasing the minorities and the weaker sections of the society. However, since the early 1980s, the Congress had tried to mobilize Hindu middle caste votes in its favour by gently fanning the activities of the VHP and exploiting the Meenakshipuram conversions of several low-caste Hindus to Islam in 1981. Rajiv Gandhi, as the prime minister, authorized the shilanyas, laying the foundation stone, for the Ram temple in Ayodhya in order to placate the VHP in 1986. So the vote game of the ruling party and the BJP-led Ram Janmabhoomi-Babri Masjid movement had polarized the electorate”. Today, we know what has been the result of such myopic political acts.

If read without any emotion, this book would come out as another text that also talks about victims, politics of violence, and the viewpoints of lynching. However, if read with some understanding of the sentiments, this book would become a primer-of-sorts for a novice reader. There is a sense of depth in the writing, which would not offend Babu (the fictional son). Rather, the profundity of the text would only spur further thinking on the issues dealt with. The reader would really appreciate the smooth movement of the text from one aspect to another – cow protection, pastoral communities, identity of castes, spread of religious dogmas, the idea of lynching as retribution, electoral politics, and most importantly, the Aryan / non-Aryan issue. In many ways, Vaidik’s book exposes important cross-examinations about our beliefs. Especially, given the present political / social milieu in India, this book presents itself as a discourse on discernment, if read that way. Helping the current young generations understand historical roots of modern-day disturbances and demonstrations, is a positive towards creating thinking public. Awkward inaccuracies (like beef eaters are criminals) fog our thoughts. This book attempts to set things right. Vaidik writes: “Our looking away from inconvenient truths, our blindness to our social privilege, and in our ability to pass off our unearned privilege as merit or as advantages earned by hard work. It makes us either remain silent or glorify non-violence as our essence. This is how, Babu, we let our silence lynch our souls”.

G Narasimha Raghavan, Associate Professor – Economics, Jansons School of Business, Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu State.

Email: [email protected]