Based on his twenty-one-year fieldwork, Jonathan P Parry authored ‘Classes of Labour: Work and Life in a Central Indian Steel Town’, in which he argued the weakening of the caste system as a principle of stratification. According to Parry, with a few exceptions, class system is key for social divisions and in determining social behaviour of individuals. Though his arguments might be valid for a single setting (Bhilai Steel Plant), their external validity is misleading. The larger social reality of the country suggests the deep-rootedness of the caste system and discrimination against people based on their caste status. This article attempts to illustrate the preceding claim by looking at evidence of caste discrimination in two institutions: police and courts.

Policing is a coercive arm of state authority, symbolising the state’s monopoly in violence over its subject citizens. They are crucial in maintaining peace and order by preventing unlawful incidents in society and apprehending offenders. It is the institution of the state that citizens encounter in their everyday life. In both colonial and postcolonial periods, they played a key role, not just in maintaining order in society, but transforming societal institutions. In ‘Police Matters: The Everyday State and Caste Politics in South India’, Radha Kumar argues that to ensure the smooth functioning of the colonial economy and to maintain order in the countryside, policemen employed their embedded ‘knowledge of caste’ to demarcate villages based on people of various castes and their resources. This distinction informed the police regarding the spaces and times that needed to be kept under surveillance, and castes to be protected. They evolved a new definition of criminality according to which certain marginalised caste groups are criminalised and men of that caste are kept under constant watch. Village officials, hailing from upper castes used their influence to file false cases on lower castes when they felt that their status quo was threatened in the villages. Inside the police station, policemen inflicted excessive torture on marginalised subjects to intimidate them. Outside the station, police are empowered to dictate the public spaces and mode of politics on streets, by limiting those spaces only to specific caste communities. This system of discriminatory policing is directly inherited from colonial to postcolonial India.

Instead of protecting the Scheduled Castes (SCs) from the crimes committed against them, policemen are sceptical about the cases filed by SCs against upper castes. According to the Status of Policing in India Report (2019), one out of five police personnel believe that the cases filed by SCs have false motivations and are unfit for investigation. It is impossible to receive timely redressal for grievances if the police did not trust SCs. So, the state has reserved a differential quota for SCs at various offices and constables in each state. But this policy is faced with two challenges. Firstly, state governments did not act effectively to fill the reserved seats with SC policemen, instead left them vacant. As Table 1 shows, in the top 5 states with the highest cases against SCs, SC officers vacancies amount to nearly half in 3 states and vacancies in constables are greater than 40% in two states. The state of Uttar Pradesh had the highest incidence of crime against SCs, and the highest vacancies in reserved seats for SC officers and constables.

Secondly, policemen in the department are not treated equally to others. Because their entry is based on differential provisions and the existence of caste stereotypes, they don’t receive equal treatment like other policemen. Only 45% of police personnel believe that SC officers in the department are given equal treatment like others. These trends reflect the powerlessness of Dalits to exercise their rights in the face of crimes against them from which they could not get protection from the police.

Table 1: Crimes against SCs and vacancies in SC reserved seats

| State | Crimes against SCs | SC Officers, % of vacancies | SC Constables, % of vacancies |

| Uttar Pradesh | 10138 | 50 | 45 |

| Bihar | 7367 | 45 | 21 |

| Madhya Pradesh | 6899 | 55 | 44 |

| Rajasthan | 6895 | 39 | 14 |

| Maharashtra | 2359 | 22 | 14 |

Source: India Justice Report (2021)

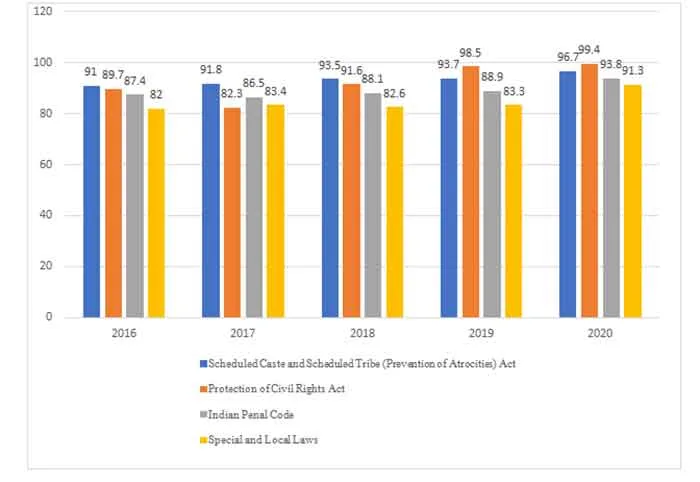

It is left to the discretion of the police to decide on whether to file a case of crime against SCs under the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, 1989 (POA Act) or the less stringent Protection of Civil Rights Act, 1955 (PCR Act), and it is argued that police give preference for the latter over POA Act. But the mere filing of cases did not mean justice was attained. Figure 1 shows the pendency rates of crimes under various laws, i.e., the number of cases pending trial at the end of the year to total cases brought for the trial. Though the pendency rates are high in all types of laws, they are highest under the POA and PCR Acts. The prospect of not getting speedy justice affects the marginalised SC sections more than others.

Figure 3: Pendency Rates in Crimes, 2016-2020

Source: NCRB

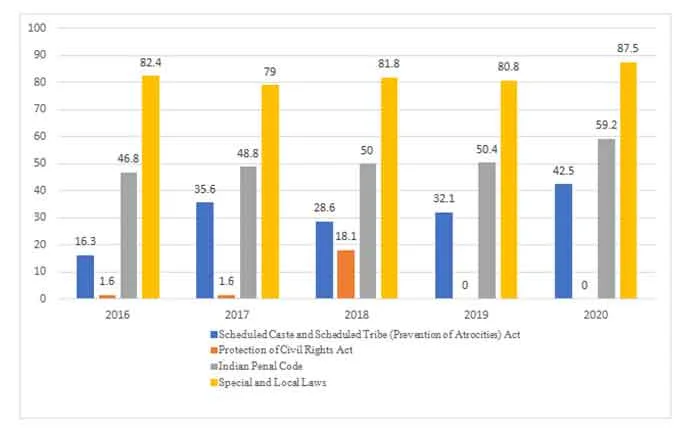

Figure 2 shows conviction rates, i.e., the percentage of cases that came to trial and received convictions. It indicates that SCs are disadvantaged even in the eyes of justice. So, longer delays in trials and lesser conviction rates affect the fundamental protections guaranteed under their citizenship rights and act as a licence for other castes to discriminate against Dalits.

Figure 4: Conviction Rates in Crimes, 2016-2020

Source: NCRB

Contrary to Parry’s claim, the caste system is deeply embedded in social institutions in India. It is important to recognise that caste operates in intersection with other systems of stratification like gender, class, religion, region etc. But its predominance as central principle of social divisions and discrimination cannot be undermined.

Mucheli Rishvanth Reddy, MSc in International Social and Public Policy (Development) from London School of Economics and Political Science