by Samik Roy Chowdhury and Gorky Chakraborty

The divisive reception received by the Citizenship Amendment Act (2019) has allowed for polarised debates on several concepts central to our political life. In this context it is only fair to ask:

How do we understand the state of citizenship in India today?

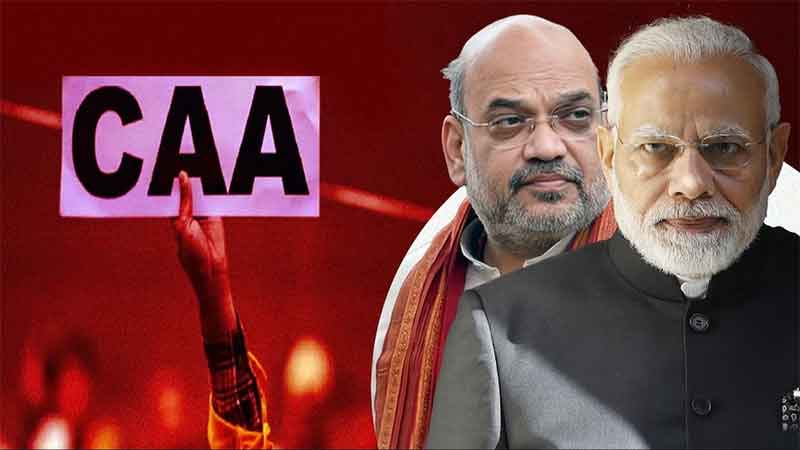

Most debates that developed around this amendment have primarily been centred on two opposing notions of citizenship and by extension nation building. This acute polarisation can be attributed to the manner in which the discussion around this bill was shaped by the present regime. The amendment exempted six ‘minority communities’, namely the Hindus, Sikhs, Jains, Parsis, Buddhists and Christians from Pakistan, Bangladesh, Afghanistan, from the category of illegal immigrants, providing them with a pathway to acquire Indian citizenship. This amendment, while controversial in itself, was linked to the creation of a nationwide register for citizens (NRC) by the union Home Minister. The purpose of the NRC, as stated by the Union home minister, was to detect and deport ‘infiltrators’.

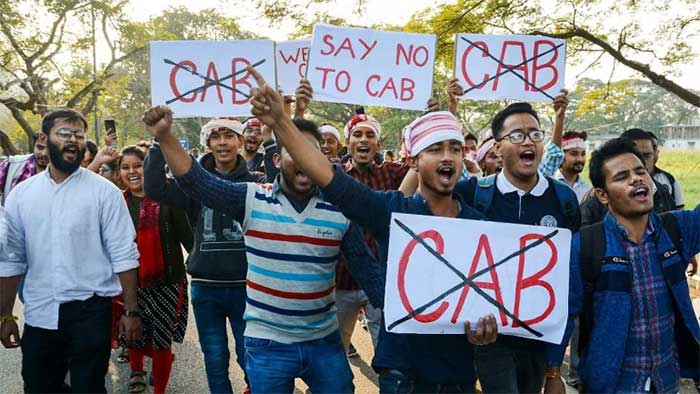

Here, it is essential to point out that often the term infiltrator is unfairly associated with specific Islamophobic and ethnic stereotypes which have been (mis)used and reproduced in various spheres of public life. Unsurprisingly, both these laws faced major opposition from the large sections of the Indian society. Most critics felt that the amendment combined with the persistent threats of NRC advanced a narrow and majoritarian narrative. Therefore, the change to the citizenship law was perceived to be detrimental to the rights and the status of the minorities, especially Muslims, and contradictory to the ‘sprit of the Indian constitution’. It was in this climate of polarisation that various popular movements developed in opposition to these laws. Unsurprisingly, the constitution emerged as a symbol of protest against this ‘unconstitutional’ amendment. The discussion on this amendment, therefore, became polarised around two opposing interpretations of constitution, citizenship and invariably nation building. On one hand, we had a majoritarian narrative which sought to correct the ‘wrongs of the partition’ by conferring citizenship to the select religious categories while on the other; we had protests calling this step unconstitutional.

So, would it suffice to characterise the present moment as a polarised one where two opposing ideas of citizenship vie for acceptance?

Unfortunately, reducing the present situation to this binary would obscure our understanding and hence, fall short in providing an answer to our question. Actually, in terms of praxis, the parameters of grating or terminating Indian citizenship have been marked by silences and in light of the recent controversies it is essential that we understand the inconsistencies, silences and the anomalies of the Indian constitution itself. The importance of understanding these silences was recently pointed out by Pratap Bhanu Mehta (Indian Express, January 25th, 2023) who highlighted how the inconsistencies of the Indian constitution have been used to undercut the principles of constitutionalism in India. This seems to be equally true when it comes to the manner in which the CAA has been articulated by its proponents.

Introducing the bill in the Lok Sabha the union Home Minister stated:

“This is a document of freedom; this is a document that would be recorded in history in golden letters….. In the end I want to, through this house, make it clear to the country, that there is a difference between refugee and immigrant…. This bill is for the refugee, this bill is for religious minorities…”

While many have pointed to the discriminatory undertone in the minister’s emphasis on the difference between a refugee and an immigrant, this objectively, is not the first time that a distinction has been made between these two ‘categories’. The most prominent example of this distinction can be found in the Immigrants (Expulsion from Assam) Act of 1950 where a distinction was made between harmful immigrants and groups seeking shelter from violence in East Bengal (now Bangladesh). In fact, this particular law in itself was used as justification for the CAA by supporters of the amendment. In essence, the present regime conflated the issue of granting formal citizenship to the victims of partition with the issue of illegal immigration. However, the reason they were able to do so was because of the inherently open-ended nature of citizenship which facilitates the oscillation of individuals and groups in and out of formal citizenship. Furthermore, this open-ended nature allows for the norms of citizenships to be determined by the electoral objectives of different regimes and the opinions of Supreme Court and High Court justices.

To understand the present uncertainty of citizenship in India it is essential to understand the patterns of granting, terminating and denying citizenship that have been practiced in India. More importantly, it is essential to recognise that any regime of citizenship, irrespective of its ideological context, is always distinct and exclusive and hence would always create spaces of non citizenship. These spaces of uncertain citizenship or non-citizenship, which exist in various parts of this country, ironically remain under-explored. Contemporary discussions on citizenship have to therefore start with these silences of citizenship. To explore these ignored spaces it becomes necessary that we understand the presence or the lack of citizenship in all its complex manifestations and transcend the traditional interpretations of citizenship.

Lastly, it is paramount that social movements and public actors (activists, public intellectuals etc.) move beyond nationalised/statist generalities and engage with the contestations and nuances of citizenship as they emerge in their specific contexts. While it seems that the present regime’s emphasis on the CAA and the NRC continues to be an electoral gimmick, the protests that develop in opposition to these policies should aspire to create a democratic space where the silences pertaining to citizenship and non-citizenship become a part of their discourse. Sole emphasis on outdated constitutional idealism may actually further the ambivalence between the imagined/visible and unexplored spaces of citizenship.

Thus, to answer the question raised earlier, it is pertinent that we explore the unresolved spaces of citizenship and its accompanying silences and understand how these silences not only define citizenship, but also create non-citizens, as evident from the recent NRC exercise in Assam.

Samik Roy Chowdhury is a PhD scholar at the Institute of Development Studies Kolkata (IDSK). He works and writes on issues related to citizenship and Migration in Northeast India.

Gorky Chakraborty is a Faculty member at Institute of Development Studies Kolkata (IDSK). He works and writes on development related issues on Northeast India