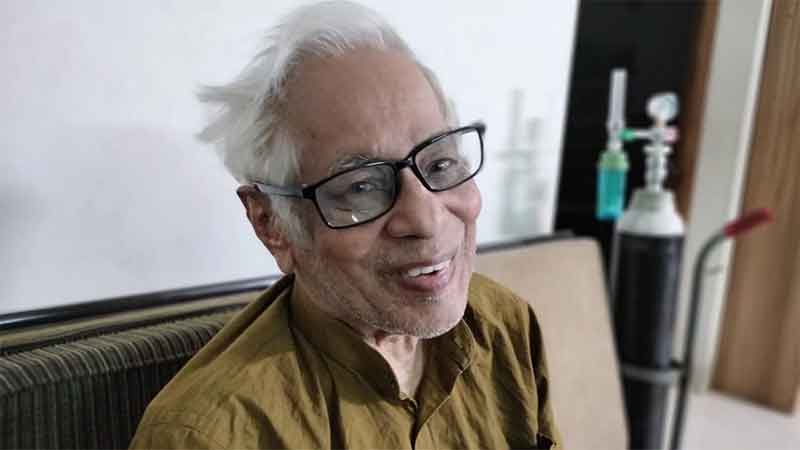

J Reghu is one of the most prominent and controversial public intellectuals in Kerala. Even in recent years, publications by Reghu have been either withdrawn due to pressure from the far right or they were burned by the far right. He studied economics at the university and he dropped out of his doctoral program, which was registered under the title “Mercantile Capitalism in Kerala”, to take part in the currents of left politics in the 1980s. Reghu had compiled, edited, and translated the writings of Kosambi when he was studying in the university. During the emergency he was interrogated by the police. He served four prison terms between 1980 – 1983, while being the state secretary of the Revolutionary Students Organisation. He was one of the figures who created a secular intellectual movement in Kerala preceding the demolition of the Babri mosque, with other eminent writers, including M. T. Vasudevan Nair. In the expanded name of Reghu Janardhanan, he is the author of several academic publications in international journals, including French, and he has published on social history of caste, positive political effects of colonial rule from the lower caste point of view, and critical theory. Among his publications is the pathbreaking long essay on Indian political history “Hindu Hoax: How Uppercastes Invented a Hindu Majority” co-authored with Divya Dwivedi and Shaj Mohan. Reghu continues to straddle the role of a public intellectual and activist, and of a researcher of political philosophy and scientific thought. Recently he retired as editor from the Kerala Encyclopaedia department.

Abhish K. Bose: The Communist ideology is not a regional ideology, however it has been a regional party in India with its presence only in Kerala, West Bengal and Tripura. Why did this happen? Now in Indian politics communist parties exist as relevant only in Kerala, where they are still in power. There are scattered presences in other states, but there is no indication of a possibility that these parties can become nationally relevant in anywhere other than Kerala. Can you explain the historical circumstances that led to the formation of the Communist movement, especially in the context of Kerala? Why did the movement begin in 1920?

Reghu: Marxist and Leninist discourse and the news about communist movements were being closely watched by many political currents in India. In Kerala and Tamil Nadu it was the lower caste leaders and intellectuals who first found the possibility of activating a communist politics as an emancipatory strategy. How many people would today know that “Sakhavu”, the Malayalam translation for the term “comrade”, was invented by Sahodaran Ayyappan, the leader of the lower castes and the president of SNDP during 1935-1941? It was in a poem written in 1919 saluting the October Socialist Revolution. The poem says,

Perennial servility was it for long,

The land of Russia had it to mourn,

But with glory at the end did it attain,

A model freedom of world renown.

Create here, oh! Comrades (Sakhaakkale), and strive apace,

And dazzle the world with echoing histories.

(Translated from Malayalam by Anil Khan)

But the upper castes could see the danger in a formation of lower castes for emancipation through a Bolshevik like movement which could have destroyed the upper castes dominance over the whole society, with international support. The upper castes who were wealthy, resourceful and had cultural and political clout soon formed their own communist movements in India. Opposed to the lower caste people’s position, that communism in the Indian context was a matter of the destruction of caste based society, the upper castes subverted it through the adoption of a class thesis.

Class as an abstract concept had no bearing on Indian society, and it does not have any bearing even now. If you compile a list of the 20 richest men in India will there be a lower caste in it? No. If you consider the biggest corruption scandals of India in recent decades will there a lower caste who amassed extreme wealth? No. So, the adoption of “class theory” was a way to eradicate the anti-caste movements. This is of course a two-pronged strategy, which combines with the invention of Hinduism.

Bose: I had conducted an interview with Prof Divya Dwivedi recently, which became viral and controversial. Prof Dwivedi spoke about the invention of “Hinduism” in 20th century as a strategy to subordinate the lower caste people under the upper castes. Her point was that as long as upper castes controlled this religion, which is almost a state religion, the lower castes as its members could never start a true liberation movement. Could you say something about this two-pronged strategy?

Reghu: I had written a long essay with Divya Dwivedi and Shaj Mohan in the Caravan Magazine titled “Hindu Hoax”. But for now I will say something from the context of Kerala. British rule had destroyed the basis for the organic concept of family, sexual life, matrilineal order of the Nairs, and their transactional power with the Namboothiris. It challenged the hypophysics of social order through the introduction of modern education, humanist discourses, and the sciences.

Throughout India, the familial and social orders were (and still are) defined by what Dwivedi and Mohan calls “hypophysics” (Gandhi and Philosophy: On Theological Anti-Politics, Bloomsbury Academic, 2019). The concept of hypophysics is a great analytical instrument and it shows that there are conceptions of nature, man and society which are neither scientific nor metaphysical. According to hypophysics the nature of a thing is identified with its value. When a thing moves away from its own nature, that thing loses value. For example, when Indians see beauty and merit only in fair skin colour. An even better example is the varna system itself. It is a hierarchy based on birth and colour. The people high in the caste ladder have perfection—the Brahmins—and as people come down the ladder they become eventually inhuman, unworthy of touch and even gaze. Hinduism is a modern appropriation of the hypophysics of caste under constitutional norms. This concept of hypophysics is essential to understand and foreground a democratic left politics in India.

It was in this context that both “Hinduism” as a religion which is recognised by the state on the one hand, and class theory as an interpretation of society on the other hand, were adopted by the upper caste people in India. They both happened at the same time. Hinduism allowed the upper castes to control the social life of the lower caste people and also represent them before the colonial government. Class theory allowed the upper castes to present Indian social ills in a way that was foreign to India, and therefore ineffective in India. Both the Congress party and the communist parties were united in these moves. This two-pronged move was very clever!

Bose: But there was a good understanding of India as a caste based oppressive society in the Marxist discourse which came from the west. Did not the upper caste leaders find their erasure of caste oppression for the illusion of “class theory” in conflict with the international left of that time?

Reghu: The upper castes were able to represent Indian society before the colonial administration through Hinduism effectively. The same thing happened with the international “communist overlords”; that is, the upper castes could become the representatives of Indian left as the vanguard through class theory. Lenin’s colonial thesis of 1919 asserted that communist parties in all colonies must support ‘bourgeosie-democratic liberation’ movements. But M.N. Roy who participated in the second congress of the Communist international, was of the view that there are different groups of ‘bourgeosie democratic movements’ and alliances could be built only on the basis of their class nature. He argued that the Indian National Congress, though a bourgeois democratic movement, could not be trusted because he apprehended that it would at some point be co-opted by the imperialists camp. On the basis of Roy’s criticism, Lenin’s original term of ‘bourgeois-democratic liberation movement’ was reframed as ‘revolutionary movements of liberation’. No matter how much they differed, both Lenin and Roy had never enquired into the indigenous nature of Indian society. They were concerned only with the conflict between imperialism represented by the British and the ‘Colony’. Had Lenin carefully read Marx’s 1853 article on India, he would have changed his colonial thesis.

But you are right about Marx who understood the casteist character of India. In ‘The Future Results of British Rule in India’, Marx portrayed British Rule as beneficial to India. Marx, though critical of colonialism, praised the British for destroying the caste villages… which, ‘had always been the solid foundation of oriental despotism. He went on to say that England had become the ‘unconscious tool of history in bringing about the revolution’. (Karl Marx, The British Rule in India, New York Herald Tribune, June 10, 1853).

In this article, quoting an official report of the British house of commons on Indian affairs, Marx observes that we must not forget this undignified, stagnant and vegetative life of caste oppression. We must not forget that these little communities were defined by distinctions of caste and slavery, that they subjugated man to external substances instead of elevating man as the sovereign of circumstances. Marx wrote, “man, the sovereign of nature fell down on his knees in adoration of Kanuman, the monkey, sabbala, the cow…. Whatever may have been the crimes of England, she was the unconscious tool of bringing about that revolution….” (Karl Marx, ibid)

Bose: From what you call the two prongs of Hinduism-Class instrument it naturally forces a question. The Brahmins are an insignificant minority in Kerala who were both the landlords and the lords of theocratic power. But their dominance continued in the communist parties of Kerala. Today it is striking that it was the Brahmin E. M. S. Namboothiripad who became the first communist chief minister of Kerala. What was the reason for it? What were his views on caste?

Reghu: This is not an easy question for me. Many of my dear friends continue to revere E. M. S., and I did meet him to discuss Kosambi when I was a student and he was serving as the General Secretary of the CPI (M) in Delhi. We also had a published dispute. He had a unique sense of humour in person. But politics is something else.

E.M.S. wanted to rescue and glorify the Brahmin past on the one hand and on the other hand he wanted to disguise himself as a communist fighting against the evil colonialism and capitalism. He reminisces his childhood as “Surrounded by temples, prayers and benevolent and malevolent gods…” (pp. 2-5, E.M.S. Namboothiripad, How I became a communist, Trivandrum, 1976) The anti-Brahminical movements by the lower caste organisations in Kerala and in Tamil Nadu spearheaded by Periyar E.V. Ramaswamy were unbearable to the young E.M.S. He uncouthly states, “the Nambudiris possessed an advantage that Nair society lacked. What was that advantage? The answer is – ‘The caste system’” (p. 59, E.M.S. Nambudiripad, the National question in Kerala, People’s Publishing House, Bombay, 1952) E.M.S. wrote these words at a time when Kerala, Tamil Nadu and Maharashtra were the hotbeds of anti-caste, anti-brahmin, militant uprising led by lower caste people. He poured scorn on the lower caste leaders for their ‘ignorance’ in not recognizing “the Civilizing mission” accomplished by the Brahmins in Kerala and other South Indian states.

Further, E. M. S. glorified and justified the caste system, in a way similar to Gandhi, but worse “The organization of caste as a superior form of the division of labour allowed for two possibilities… The development of productive forces was given an impetus by the new social division which led to accumulation of wealth, division of labour and the division of society into classes”. (E.M.S. ibid.)

Bose: What was the relation E. M. S. had with lower caste emancipatory movements? Did anything progressive happen through his encounters with the lower caste movements? How are he and other upper caste Marxist leaders perceived today?

Reghu: Narayana Guru, Dr. Palpu, Sahodaran Ayyappan, Periyar E.V. Ramaswamy, Dr. Ambedkar were viewed by E.M.S. as ‘the Sandmen’ who haunted his Brahmin-ness which was camouflaged under the rosy picture of communism. His lifelong ambition and project was to exorcise “the Sand Men” and for him communism was the bewitching invocation.

E.M.S. occasionally praised the progressive nature of the lower caste movement, but since the ‘progressiveness’ comes from the bottom filthy layer of the caste hierarchy, it deserves to be ‘purified’ by subduing it to the top. This top position was the pure domain of ‘nationalism and class struggle’, which were led by the upper castes under the “Hindu” and “Communist” banners. In the hierarchy created by E.M.S., nationalist politics becomes paramount not because he believed that politics was the domain of freedom and revolution but precisely because his own brahmin kinsmen and other upper castes happened to be associated with it. That was why he was unapologetic in chastising and disparaging the lower caste leaders for their refusal of the communist rhetorical narrative of anti imperialism as the ‘principal contradiction’. This thesis of the principal contradiction was presented to trivialize and demonize the anti-caste struggle and the lower cast movements.

With the formation of SNDP (Sree Narayana Dharma Paripalana Yogam) of the Ezhavas in 1903 and SJPS (Sadhu Jana Paripalana Sangham) of Pulayas in 1907, both untouchable castes, there was a determined refusal by the lower castes “to live in the old way”, which in turn, entailed the inability of the upper castes to maintain the traditional way of life. It was this forced deprivation of the ‘natural right’ to be the oppressors and dehumanizers, had hurled the Nambudiri-Nairs in a state of fear and uncertainty. The previously acquiescent lower castes began to contempt, deride and challenge the upper castes pretense of superiority. This created a situation in which the newly educated Nambudiri-nairs desperately sought for a place, acceptable to the rebellious lower castes. Communism became a panacea to anchor themselves and also to justify themselves.

For the founders of Communism in Kerala, their very existence was in a horror. The presence of the British generated two “spectres’’ for the upper castes, one the attrition of their own inner life, and, the second the “horror” of the awakening of those hitherto despised as subhumans to the self-aware “humans”. Their questions and rebellions started to tear down the ‘dharmic domain’ of the upper caste privilege and power. For the upper castes, this was extremely melancholic and made them to find solace behind the mask of communism. Dr. Palpu, Narayana Guru, Ayyankali and Sahodaran Ayyappan were the lower caste adventurers who had undergone the perturbing but enlightening experience of being exposed to new ideas and values. They dared not “wish for the easier life of ignorance” imposed and institutionalized by the Nambudiri–Nair leeches. (Jim Josefson, Political philosophy. In the Moment. Narratives of freedom from Plato to Arendt, Routledge, New York, 2019, p.11)

What impacted the Nambudiri-Nairs during the British rule was that they were no longer able to perpetuate the “wish for the easier life of ignorance”. The upper castes’ unfettered authority to deny the lower castes the fundamental human right ‘to live in freedom and dignity’, their customary power to exploit the labour of the lower castes and humiliate them had been undermined. The British rule was a fatal blow on the Nambudiri-Nair self, built on arrogance, exploitation and barbarism. What was solid like a rock for many, many centuries began to melt away. This was, to use a phrase of Milan Kundera, “the unbearable lightness of being” (by lightness Kundera means insignificant, wispy or evanacent). In the early decades of 20th century, the Nambudiri-Nairs were thrown into such an “unbearable lightness of being”.

Bose: Why did Dr. Ambedkar never trust Indian communist?

Reghu: Dr. Ambedkar had a theoretical and pragmatic understanding of what was taking place in India in the name of “communism” led by the upper caste people. He already made it clear that – “The governing class in India is a Brahmin–Bania combine”, and not a vague bourgeoisie. He scorns it, but in India surprisingly the ‘supercilious brahmins’ are found to have been preaching the ideals of Marx with red flags in their hands which are already stained with the bloodspots of the helpless producer classes called Sudras…. It is surprising that Indian ‘popes’ have actually come down to revolt against the ‘popedom’ trying to be revolutionaries (cited in, Swapan K. Biswas, Nine Decades of Marxism in the land of Brahminism, Other books, Calicut, Kerala 2008, p.22)

Ambedkar observes, “the brahminical communists have always been well aware of the class-cum-caste status and the role they were to play in it…. Therefore, they invented a suitable terminology to tackle the challenge of their anti-Marxist caste bias. Indian Marxist had fancifully invented a term, “de-classing” and always use to refer to the term “De-classed”. They used the term to refer to the governing caste members who wanted to follow and preach Marxism…” (S.K. Biswas, ibid, pp. 43-45) That is, just as “Hinduism” was a tool for the upper castes to hide their oppressor status before modern constitutional set-ups, “de-class” and “communism” were another tool for them to hide their oppressor position in society. So, for Ambedkar both “Hindu” and “Marxism” were new instruments of oppression which were also simultaneously able to hide the long history of oppression.

Bose: Certainly the class abstraction is an utter failure to understand India, and as you pointed out it is a strategy to avoid any discussion of caste. But all this raises other questions. Why is it that the caste question is not properly theorised for an emancipatory politics in India? Without such theoretical tools, formulae, and formulations can caste oppression be overcome?

Reghu: Caste oppression or any form of oppression requires that we have a sufficient understanding of the specific character of that oppression. As Marx said in his eleventh thesis, interpretation is a necessary condition, and action is the sufficient condition. But we can know what is the best course of action only when the necessary theory emerges. Even in our own times, the problem of a real theory remains, that “what is lacking”, as Balibar pointed out, “is any articulation between the social, the political and the theoretical” ( in Etienne Balibar and Immanuel Wallerstein, Race, Nation, Class: Ambiguous Identities, Verso, London, 1991).

There are theoretical resources in Ambedkar, Sahodaran Ayyappan, Narayana Guru, Periyar and many other great lower caste leaders. They were great interpreters of India with regard to the caste system. But these resources have to be updated. In that direction there are two concepts which I find absolutely necessary — hypophysics and Calypsology — created by Dwivedi and Mohan.

Hypophysics, as I said earlier, shows the real character of the Varna (skin colour) theory and Guna (properties) theory which informs everyday conduct of caste oppression. Hypophysics equates nature and value. A thing loses its value as it falls further away from its nature. Hypophysics identifies the value of each human life on the basis of birth—a Brahmin has more value as he is the purest of nature and therefore he sits at the top of the hierarchy. A Dalit is condemned to live a poor life away from shiny modern institutions because he fell furthest from the Brahmin through his birth. On the other hand the Kshatriyas and the Baniyas are the closest to the Brahmins, so they are more valuable. When I say valuable, today in the eyes of modern legal institutions you can see how caste discrimination works.

Calypsology is the logic of the caste system. It shows something simple: Caste system which observes vigilance over who marries who, or the sexual freedom of women, ensures that caste system is perpetuated. That is, according to calypsology caste system ensures its repetition and prolongation through the reproduction of caste system; the very meaning of reproduction here is simply the control of biological and social reproduction of the “division of labourers” as Ambedkar showed.

Instead of economic determinism of society if we adopt the theory of hypophysics and instead of class analysis we adopt the logic of Calypsology, Indian society will show its true character. Then we can start to think of emancipatory projects and strategies.

Bose: This is interesting because the only two public figures, who are internationally recognised philosophers, who speak about revolution in India are Dwivedi and Mohan, in their joint writings and individual writings. But is there a theory of revolution or social transformation in their works, which can replace Marxist pathways?

Reghu: There is something which can be called a revolutionary theory, but not under that name. Dwivedi and Mohan call it anastasis, in the sense of that which displaces the stasis of a society (Gandhi and Philosophy, 2019). In India it is caste that is the stasis. If you read their book “Gandhi and Philosophy: On Theological Anti-politics” attentively it will become clear, especially the final chapter and the foreword by Jean-Luc Nancy. But as Robert Bernasconi said about it, it is a difficult book but most rewarding at the same time.

I have myself in two academic essays interpreted that possibility in their works under a different name as “deconstructive materialism” by placing an emphasis on politics, and Jean-Luc Nancy liked this name. For me, deconstructive materialism is about the possibilities released through the analysis of an object or of a society. To give one example for this interview, when you deconstruct gender, all kinds of materialist possibilities appear for people to live by. This is the making of freedom or politics.

In India, if we deconstructively release the material forces of society, that is to say the possibilities denied to the lower caste people, they will raise a new social order and a more just political state. This can be called the anastasis of politics in India. For that reason the Dalit – Bahujans, the lower castes of all religions in India constitute the real left in India. Only they can be the agency of revolution in India because it is they who have the maximum material possibilities.

Bose: Do the Communist parties have a future in India? And is there any meaning in saying that somebody is in the left and somebody else is in the right in politics in India now?

Reghu: I don’t think that the existing ‘communist’ parties have any future in India, because they are communist only in name; it is therefore a meaningless label. At the same time we should not hesitate to say an emphatic ‘No’ to the right wing and liberal dream, that the ‘left’/right political distinction has been buried deep. With all the rhetoric of right wing and the ascendency of rightist ghosts in certain countries, the question of the political distinction has become all the more urgent and important. It should be remembered that left and right were not rigid, absolute things. What is left at one place and in one period may be right in another place and time. At the same time, there is no in between or midway between the left and right spectrums of political life and according Norberto Bobbio, ‘nothing in politics can be both left and right at the same time” (N. Bobbio, The Left and Right: The significance of a political distinction, University of Chicago press, 1996. ibid, P.X.)

Bobbio adamantly defends the left/right political distinction, because, according to him, “the left tends towards equality and the right tends towards inequality. Bobbio distances himself from the liberal discourse of ‘inclusion/exclusion’ because it is only peripheral. It is true that inclusion/exclusion paradigm sometimes welcome immigrants, grant them citizen rights, stop discrimination on the basis of foreign origin. But for, Bobbio, equality is not embedded in inclusion, care, etc, but in Justice and freedom. For Bobbio, justice implies two principles: rule of law and equality (all are entitled to be equal before the law). Equality is the particular instantiation of the absolute, the abstract and the universal, which is Justice. The difference between left and right is in the approach to the question of the degree within which a particular historical and cultural composition deals with the questions of equality and inequality.

Massimo Cacciari argues that, “Equality makes diversity possible, makes it possible to count everyone as a person, quite unlike that abstract totalitarian idea of equality which means the elimination of those who are not the same”. (Massimo Caccaiari, ‘Dialoghetto Sulla “Senisters”, Micro Mega, 1993, 4, P.15)

Again, from this it is clear that the real left in India are the Dalit-Bahujan majority and those who take the lower caste position in politics in India. Because those are the people who strive for an egalitarian political order.

Bose: Finally, can there be a communist today? Or what is the meaning of being a communist in this time?

Reghu: I think I am communist in my everyday life. I share everything I have and my friends share with me. If a friend comes to town they live with me. In a very Marxist way, people can move as much as possible away from the tyranny of the market through sharing, and also making things. In this way there is a kind of communism of everyday life I practice and I urge everyone to practice. I try my best not to mediate my everyday life with my friends through the market. But it falls short of politics, which is about creating freedom collectively. So communism now is a kind of moral rule.

There is another meaning of being a communist, which I hold to be important for the formation of political movements from the left position. It is to belong to and participate in a community as Jean-Luc Nancy defined it; for him the reality of a human community was the very fact of the human capacity to come together without attributing to this community any particular essence (Nancy, The Inoperative Community, University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, 1991). The community has only one meaning in Nancy’s work, the “being-with” of the people and that is why he called it “inoperative community”. Human beings don’t have any transcendent ends, or super-sensible values to hold on to, which were destroyed by philosophy and the sciences. So we are today “forsaken” from the point of view of transcendent goals. So this kind of community can also be interpreted as a fact of humanity today as “the forsaken community” as Dwivedi and Mohan called it, and you know that Nancy, Stiegler, Dwivedi and Mohan were friends. The point I am making here is something more. You need to first imagine and practice living and thinking together as a community in this way so that you can create political movements for freedom.