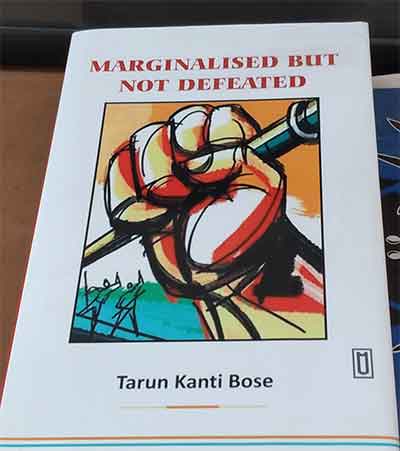

Marginalised but not Defeated

Tarun Kanti Bose

Uppal Publishing House

Price: 1,295

Year: 2023

Pg: 277

The book, like the author, a seasoned public interest journalist, travels far and wide, among ordinary and invisible people, in remote regions, across the fragmented landscape of India. Tarun Kanti Bose writes about the demography, topography, society, politics and culture, and the anthropology and agricultural practices of civilizations who have survived the infinite difficulties of their life and times, faced with State repression or indifference, as much as the apocalyptic paradigm shifts witnessed by ecological devastation. These are the original people making the ancient and contemporary roots of the Indian inheritance, before and after the making of the Indian Constitution.

The book is a meticulous documentation of journeys, road and railway lines, the network of rivers and human civilizations, villages and small towns, talukas and tribal hamlets. Witness this intricate description: “The Tapi river passes through Khandesh region with black soil and fertile plains along its bank. It flows east-west across the district cutting Nandurbar district into two almost equal halves. It forms the basin from the beginning of Shahada taluka which broadens into a strip of extremely fertile plains of about 15-20 miles in width at its broadest. In the north of the Shahada and Talode talukas, the plains end with a steep rise of the Satpura range which forms ridges of the rising mountains. Most of the part of Akkalkuwa taluka which bounds the Talode taluka on the west is taken up by the Satpura range with a relatively narrow strip of the north-west basin included in the southern region. The Nandurbar district lies to the south of the Tapi river. Here the plains end with a slow rise and increasingly rocky soil that blend into the Sahyadri and Galna hills in the south-west…”

The book is a meticulous documentation of journeys, road and railway lines, the network of rivers and human civilizations, villages and small towns, talukas and tribal hamlets. Witness this intricate description: “The Tapi river passes through Khandesh region with black soil and fertile plains along its bank. It flows east-west across the district cutting Nandurbar district into two almost equal halves. It forms the basin from the beginning of Shahada taluka which broadens into a strip of extremely fertile plains of about 15-20 miles in width at its broadest. In the north of the Shahada and Talode talukas, the plains end with a steep rise of the Satpura range which forms ridges of the rising mountains. Most of the part of Akkalkuwa taluka which bounds the Talode taluka on the west is taken up by the Satpura range with a relatively narrow strip of the north-west basin included in the southern region. The Nandurbar district lies to the south of the Tapi river. Here the plains end with a slow rise and increasingly rocky soil that blend into the Sahyadri and Galna hills in the south-west…”

Witness the description of another travel trajectory: “The Mumbai-Agra Road passes through the eastern part of Nandurbar district through Shule and Shirpur and along one of the old trade routes of India. The Mumbai-Delhi railway route pases through Jalgoan district of Khandesh regision. The Surat-Bhusawal railway line follows the south bank of the river Rapi throughout the region. Prakeshe village, which lies at the confluence of the Tapi and the Gomai rivers in Shahada taluka, has been the most important nodal link in earlier days…”

So what is grown in the Khandesh region? Cereals, millets and pulses. Cotton, sugarcane, vegetables, edible fruit-yielders and spices. Oil, cotton, starch, sugar, pulses, timber. Sorghum, jowar, pearl millet, wheat, maize, rice, black gram, horse gram, mung bean, pigeon pea. Plus, sugarcane, banana and other cash crops. All in the plains, valleys, hills and forests – by the villagers and ancient adivasis. And, yet, why are the people, the locals, the inheritors of this fertile land, so transparently poor, and so brazenly exploited and oppressed, and by whom?

For instance, post-pandemic, adivasi migrant workers have nourished these sugar mills owned by powerful politicians in Gujarat and MP. Tarun writes that they worked in over 100 different sugarcane cooperatives, and thereby were forced to travel back to Maharashtra since the owners of the factories refused to take responsibility. The adivasis returned without their wages. No food or travel allowance was given to them.

Documenting the fisherfolk communites during the difficult and forcibly enforced lockdown, the book narrates that fisher communities, especially in Mumbai, were rendered jobless. It became difficult to make two ends meet since all the fish markets were closed till August 2020. Many of them, even later. “During the pandemic, small-scale fishers, both in the inland and marine sector, found it rough to continue fishing. Fisher folk across the west coast of India threw away their fresh fish catch. In the absence of ice, there could not be any storage. The fish could not be sold as there were neither exporters nor traders. As there were no loaders for loading and unloading of fish, the transport of stock and ice and other sundry jobs, which were labour-intensive and integral, could not be done. The fisher folk who returned from the sea did not know what to do with their stock, so they threw it away or sold it at meager prices…”

Women, especially single women, who constitute a majority of fish vendors at markets, by the roadside, by headloading for door-to-door sale, were the hardest hit by the loss of access to fish, lack of transport. Markets and consumers. “Their day to day subsistence economy took a hit so the impact at the household level was sever.” Hence, the busiest fish markets in Mumbai – Crawford Market in south Mumbai, Sassoon Dock in Colaba, Bhauccha Dhaka near the Dockyard, and the Kasara fish market in Thane, became quiet, with no business happening, the hustle and bustle buried in the despair and joblessness of the lockdown. This was a big crisis, and they are still trying to recover from it.

The book travels across the Hindi hinterland, onwards to the west, Gujarat and Maharashtra, then to the East, Bengal, Bihar and Jharkhand, and covers the various tribal regions in the remote and sublime landscape of North-east India. It talks about the Khasis, Nagas, Karbis, Garos, Rabhas, Misings, Daflas, Bodos, Akas and others in the North-east. It enters the invisible lives of the Santhals, Mundas, Hos, Kharias, Paherias, Oraons, Mundas, Bhils, Gonds, Kols, Koyas, Todas, Banjaras, etc in the Central Provinces, in Dandakaranya and Jharkhand, among the 550 tribal communities in India.

The book documents the hard and difficult struggle to implement the Forest Rights Act, how the oppressed adivasis have united into forest unions, how they are now entering into new thresholds of protracted struggles and victories in a non-violent manner. The mainstream development paradigm is being questioned and new rainbows of collective, community reassertions are happening across the tribal belt in India. More so, in most cases, led by brave, empowered and resilient women.

That is why the name of the book: Marginalised but not Defeated. A must for all young journalists, social science students, editors, civil society groups and the academia.

Amit Sengupta is a journalist