by C.J. Polychroniou and Noam Chomsky

Artificial intelligence (AI) is sweeping the world. It is transforming every walk of life and raising in the process major ethical concerns for society and the future of humanity. ChatGPT, which is dominating social media, is an AI-powered chatbot developed by OpenAI. It is a subset of machine learning and relies on what is called Large Language Models that can generate human-like responses. The potential application for such technology is indeed enormous, which is why there are already calls to regulate AI like ChatGPT.

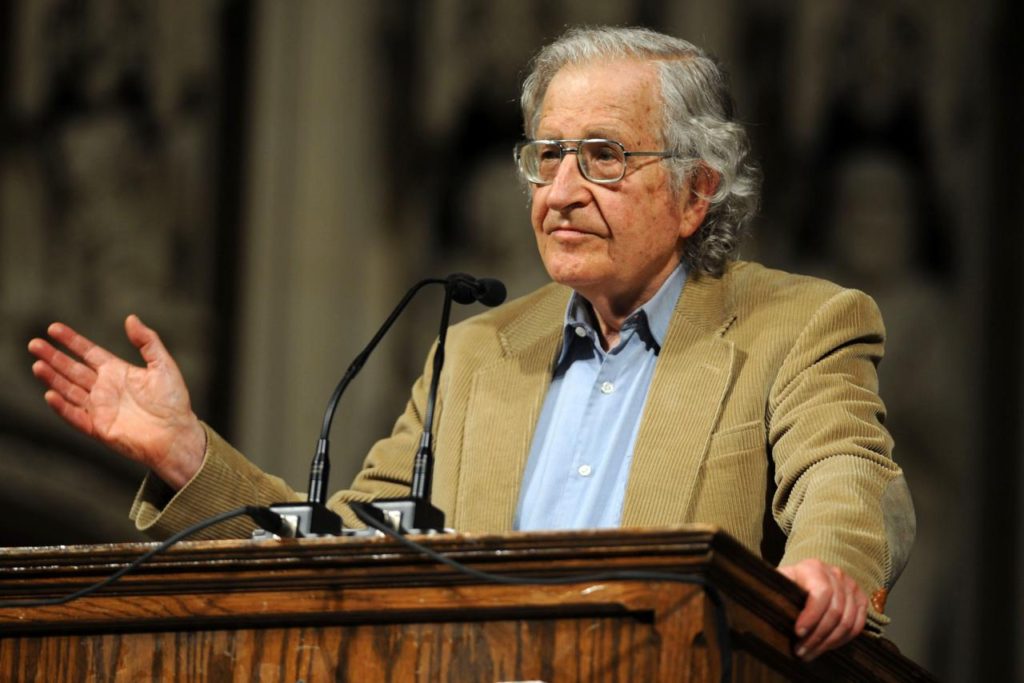

Can AI outsmart humans? Does it pose public threats? Indeed, can AI become an existential threat? The world’s preeminent linguist Noam Chomsky, and one of the most esteemed public intellectuals of all time, whose intellectual stature has been compared to that of Galileo, Newton, and Descartes, tackles these nagging questions in the interview that follows.

C. J. Polychroniou: As a scientific discipline, artificial intelligence (AI) dates back to the 1950s, but over the last couple of decades it has been making inroads into all sort of fields, including banking, insurance, auto manufacturing, music, and defense. In fact, the use of AI techniques has been shown in some instance to surpass human capabilities, such as in a game of chess. Are machines likely to become smarter than humans?

Noam Chomsky: Just to clarify terminology, the term “machine” here means program, basically a theory written in a notation that can be executed by a computer–and an unusual kind of theory in interesting ways that we can put aside here.

We can make a rough distinction between pure engineering and science. There is no sharp boundary, but it’s a useful first approximation. Pure engineering seeks to produce a product that may be of some use. Science seeks understanding. If the topic is human intelligence, or cognitive capacities of other organisms, science seeks understanding of these biological systems.

As I understand them, the founders of AI–Alan Turing, Herbert Simon, Marvin Minsky, and others–regarded it as science, part of the then-emerging cognitive sciences, making use of new technologies and discoveries in the mathematical theory of computation to advance understanding. Over the years those concerns have faded and have largely been displaced by an engineering orientation. The earlier concerns are now commonly dismissed, sometimes condescendingly, as GOFAI–good old-fashioned AI.

Continuing with the question, is it likely that programs will be devised that surpass human capabilities? We have to be careful about the word “capabilities,” for reasons to which I’ll return. But if we take the term to refer to human performance, then the answer is: definitely yes. In fact, they have long existed: the calculator in a laptop, for example. It can far exceed what humans can do, if only because of lack of time and memory. For closed systems like chess, it was well understood in the ‘50s that sooner or later, with the advance of massive computing capacities and a long period of preparation, a program could be devised to defeat a grandmaster who is playing with a bound on memory and time. The achievement years later was pretty much PR for IBM. Many biological organisms surpass human cognitive capacities in much deeper ways. The desert ants in my backyard have minuscule brains, but far exceed human navigational capacities, in principle, not just performance. There is no Great Chain of Being with humans at the top.

The products of AI engineering are being used in many fields, for better or for worse. Even simple and familiar ones can be quite useful: in the language area, programs like autofill, live transcription, google translate, among others. With vastly greater computing power and more sophisticated programming, there should be other useful applications, in the sciences as well. There already have been some: Assisting in the study of protein folding is one recent case where massive and rapid search technology has helped scientists to deal with a critical and recalcitrant problem.

Engineering projects can be useful, or harmful. Both questions arise in the case of engineering AI. Current work with Large Language Models (LLMs), including chatbots, provides tools for disinformation, defamation, and misleading the uninformed. The threats are enhanced when they are combined with artificial images and replication of voice. With different concerns in mind, tens of thousands of AI researchers have recently called for a moratorium on development because of potential dangers they perceive.

As always, possible benefits of technology have to be weighed against potential costs.

Quite different questions arise when we turn to AI and science. Here caution is necessary because of exorbitant and reckless claims, often amplified in the media. To clarify the issues, let’s consider cases, some hypothetical, some real.

I mentioned insect navigation, which is an astonishing achievement. Insect scientists have made much progress in studying how it is achieved, though the neurophysiology, a very difficult matter, remains elusive, along with evolution of the systems. The same is true of the amazing feats of birds and sea turtles that travel thousands of miles and unerringly return to the place of origin.

Suppose Tom Jones, a proponent of engineering AI, comes along and says: “Your work has all been refuted. The problem is solved. Commercial airline pilots achieve the same or even better results all the time.”

If even bothering to respond, we’d laugh.

Take the case of the seafaring exploits of Polynesians, still alive among Indigenous tribes, using stars, wind, currents to land their canoes at a designated spot hundreds of miles away. This too has been the topic of much research to find out how they do it. Tom Jones has the answer: “Stop wasting your time; naval vessels do it all the time.”

Same response.

Let’s now turn to a real case, language acquisition. It’s been the topic of extensive and highly illuminating research in recent years, showing that infants have very rich knowledge of the ambient language (or languages), far beyond what they exhibit in performance. It is achieved with little evidence, and in some crucial cases none at all. At best, as careful statistical studies have shown, available data are sparse, particularly when rank-frequency (“Zipf’s law”) is taken into account.

Enter Tom Jones: “You’ve been refuted. Paying no attention to your discoveries, LLMs that scan astronomical amounts of data can find statistical regularities that make it possible to simulate the data on which they are trained, producing something that looks pretty much like normal human behavior. Chatbots.”

This case differs from the others. First, it is real. Second, people don’t laugh; in fact, many are awed. Third, unlike the hypothetical cases, the actual results are far from what’s claimed.

These considerations bring up a minor problem with the current LLM enthusiasm: its total absurdity, as in the hypothetical cases where we recognize it at once. But there are much more serious problems than absurdity.

One is that the LLM systems are designed in such a way that they cannot tell us anything about language, learning, or other aspects of cognition, a matter of principle, irremediable. Double the terabytes of data scanned, add another trillion parameters, use even more of California’s energy, and the simulation of behavior will improve, while revealing more clearly the failure in principle of the approach to yield any understanding. The reason is elementary: The systems work just as well with impossible languages that infants cannot acquire as with those they acquire quickly and virtually reflexively.

It’s as if a biologist were to say: “I have a great new theory of organisms. It lists many that exist and many that can’t possibly exist, and I can tell you nothing about the distinction.”

Again, we’d laugh. Or should.

Not Tom Jones–now referring to actual cases. Persisting in his radical departure from science, Tom Jones responds: “How do you know any of this until you’ve investigated all languages?” At this point the abandonment of normal science becomes even clearer. By parity of argument, we can throw out genetics and molecular biology, the theory of evolution, and the rest of the biological sciences, which haven’t sampled more than a tiny fraction of organisms. And for good measure, we can cast out all of physics. Why believe in the laws of motion? How many objects have actually been observed in motion?

There is, furthermore, the small matter of burden of proof. Those who propose a theory have the responsibility of showing that it makes some sense, in this case, showing that it fails for impossible languages. It is not the responsibility of others to refute the proposal, though in this case it seems easy enough to do so.

Let’s shift attention to normal science, where matters become interesting. Even a single example of language acquisition can yield rich insight into the distinction between possible and impossible languages.

The reasons are straightforward, and familiar. All growth and development, including what is called “learning,” is a process that begins with a state of the organism and transforms it step-by-step to later stages.

Acquisition of language is such a process. The initial state is the biological endowment of the faculty of language, which obviously exists, even if it is, as some believe, a particular combination of other capacities. That’s highly unlikely for reasons long understood, but it’s not relevant to our concerns here, so we can put it aside. Plainly there is a biological endowment for the human faculty of language. The merest truism.

Transition proceeds to a relatively stable state, changed only superficially beyond: knowledge of the language. External data trigger and partially shape the process. Studying the state attained (knowledge of the language) and the external data, we can draw far-reaching conclusions about the initial state, the biological endowment that makes language acquisition possible. The conclusions about the initial state impose a distinction between possible and impossible languages. The distinction holds for all those who share the initial state–all humans, as far as is known; there seems to be no difference in capacity to acquire language among existing human groups.

All of this is normal science, and it has achieved many results.

Experiment has shown that the stable state is substantially obtained very early, by three to four years of age. It’s also well-established that the faculty of language has basic properties specific to humans, hence that it is a true species property: common to human groups and in fundamental ways a unique human attribute.

A lot is left out in this schematic account, notably the role of natural law in growth and development: in the case of a computational system like language, principles of computational efficiency. But this is the essence of the matter. Again, normal science.

It is important to be clear about Aristotle’s distinction between possession of knowledge and use of knowledge (in contemporary terminology, competence and performance). In the language case, the stable state obtained is possession of knowledge, coded in the brain. The internal system determines an unbounded array of structured expressions, each of which we can regard as formulating a thought, each externalizable in some sensorimotor system, usually sound though it could be sign or even (with difficulty) touch.

The internally coded system is accessed in use of knowledge (performance). Performance includes the internal use of language in thought: reflection, planning, recollection, and a great deal more. Statistically speaking that is by far the overwhelming use of language. It is inaccessible to introspection, though we can learn a lot about it by the normal methods of science, from “outside,” metaphorically speaking. What is called “inner speech” is, in fact, fragments of externalized language with the articulatory apparatus muted. It is only a remote reflection of the internal use of language, important matters I cannot pursue here.

Other forms of use of language are perception (parsing) and production, the latter crucially involving properties that remain as mysterious to us today as when they were regarded with awe and amazement by Galileo and his contemporaries at the dawn of modern science.

The principal goal of science is to discover the internal system, both in its initial state in the human faculty of language and in the particular forms it assumes in acquisition. To the extent that this internal system is understood, we can proceed to investigate how it enters into performance, interacting with many other factors that enter into use of language.

Data of performance provide evidence about the nature of the internal system, particularly so when they are refined by experiment, as in standard field work. But even the most massive collection of data is necessarily misleading in crucial ways. It keeps to what is normally produced, not the knowledge of the language coded in the brain, the primary object under investigation for those who want to understand the nature of language and its use. That internal object determines infinitely many possibilities of a kind that will not be used in normal behavior because of factors irrelevant to language, like short-term memory constraints, topics studied 60 years ago. Observed data will also include much that lies outside the system coded in the brain, often conscious use of language in ways that violate the rules for rhetorical purposes. These are truisms known to all field workers, who rely on elicitation techniques with informants, basically experiments, to yield a refined corpus that excludes irrelevant restrictions and deviant expressions. The same is true when linguists use themselves as informants, a perfectly sensible and normal procedure, common in the history of psychology up to the present.

Proceeding further with normal science, we find that the internal processes and elements of the language cannot be detected by inspection of observed phenomena. Often these elements do not even appear in speech (or writing), though their effects, often subtle, can be detected. That is yet another reason why restriction to observed phenomena, as in LLM approaches, sharply limits understanding of the internal processes that are the core objects of inquiry into the nature of language, its acquisition and use. But that is not relevant if concern for science and understanding have been abandoned in favor of other goals.

More generally in the sciences, for millennia, conclusions have been reached by experiments–often thought experiments–each a radical abstraction from phenomena. Experiments are theory-driven, seeking to discard the innumerable irrelevant factors that enter into observed phenomena–like linguistic performance. All of this is so elementary that it’s rarely even discussed. And familiar. As noted, the basic distinction goes back to Aristotle’s distinction between possession of knowledge and use of knowledge. The former is the central object of study. Secondary (and quite serious) studies investigate how the internally stored system of knowledge is used in performance, along with the many non-linguistic factors than enter into what is directly observed.

We might also recall an observation of evolutionary biologist Theodosius Dobzhansky, famous primarily for his work with Drosophila: Each species is unique, and humans are the uniquest of all. If we are interested in understanding what kind of creatures we are–following the injunction of the Delphic Oracle 2,500 years ago–we will be primarily concerned with what makes humans the uniquest of all, primarily language and thought, closely intertwined, as recognized in a rich tradition going back to classical Greece and India. Most behavior is fairly routine, hence to some extent predictable. What provides real insight into what makes us unique is what is not routine, which we do find, sometimes by experiment, sometimes by observation, from normal children to great artists and scientists.

One final comment in this connection. Society has been plagued for a century by massive corporate campaigns to encourage disdain for science, topics well studied by Naomi Oreskes among others. It began with corporations whose products are murderous: lead, tobacco, asbestos, later fossil fuels. Their motives are understandable. The goal of a business in a capitalist society is profit, not human welfare. That’s an institutional fact: Don’t play the game and you’re out, replaced by someone who will.

The corporate PR departments recognized early on that it would be a mistake to deny the mounting scientific evidence of the lethal effects of their products. That would be easily refuted. Better to sow doubt, encourage uncertainty, contempt for these pointy-headed suits who have never painted a house but come down from Washington to tell me not to use lead paint, destroying my business (a real case, easily multiplied). That has worked all too well. Right now it is leading us on a path to destruction of organized human life on earth.

In intellectual circles, similar effects have been produced by the postmodern critique of science, dismantled by Jean Bricmont and Alan Sokal, but still much alive in some circles.

It may be unkind to suggest the question, but it is, I think, fair to ask whether the Tom Joneses and those who uncritically repeat and even amplify their careless proclamations are contributing to the same baleful tendencies.

CJP: ChatGPT is a natural-language-driven chatbot that uses artificial intelligence to allow human-like conversations. In a recent article in The New York Times, in conjunction with two other authors, you shut down the new chatbots as a hype because they simply cannot match the linguistic competence of humans. Isn’t it however possible that future innovations in AI can produce engineering projects that will match and perhaps even surpass human capabilities?

NC: Credit for the article should be given to the actual author, Jeffrey Watumull, a fine mathematician-linguist-philosopher. The two listed co-authors were consultants, who agree with the article but did not write it.

It’s true that chatbots cannot in principle match the linguistic competence of humans, for the reasons repeated above. Their basic design prevents them from reaching the minimal condition of adequacy for a theory of human language: distinguishing possible from impossible languages. Since that is a property of the design, it cannot be overcome by future innovations in this kind of AI. However, it is quite possible that future engineering projects will match and even surpass human capabilities, if we mean human capacity to act, performance. As mentioned above, some have long done so: automatic calculators for example. More interestingly, as mentioned, insects with minuscule brains surpass human capacities understood as competence.

CJP: In the aforementioned article, it was also observed that today’s AI projects do not possess a human moral faculty. Does this obvious fact make AI robots less of a threat to the human race? I reckon the argument can be that it makes them perhaps even more so.

NC: It is indeed an obvious fact, understanding “moral faculty” broadly. Unless carefully controlled, AI engineering can pose severe threats. Suppose, for example, that care of patients was automated. The inevitable errors that would be overcome by human judgment could produce a horror story. Or suppose that humans were removed from evaluation of the threats determined by automated missile-defense systems. As a shocking historical record informs us, that would be the end of human civilization.