Gobindo, the fish-seller, sat smoking bidis, amidst piles of silvery, shining fishes of different kinds, every evening, just where the street began as an off-shoot from the Lake Town main road, near the Lake Town bus stop in Kolkata. Not only did he sell the best quality ones, he customarily handled old customers and new ones with equal familiarity and a certain elan, and he was an expert at mentally calculating weights and prices of multiple purchases of different customers all at once. His wife, a very efficient woman, cut the fishes into pieces, and their son, who went on to college after finishing school, helped her by meticulously de-scaling the fishes first. The golden light bulbs hanging from above lit up the eyes of Gobindo and his family, much more than their silvery ware perhaps. In fact, I still remember Gobindo, a short tight lungi-clad, his naked torso glistening with sweat, and his wife’s forehead smeared with vermillion, bent over the sharpest, biggest “boti”, busy cutting fishes into pieces. And out of all the talk about fishes and prices, I remember my father catching up with the son’s performance in the exam, and which subjects he liked. This constitutes a lasting childhood memory. Of the times I went to the market with my father, which was quite often.

Nowadays though, at 1am in the night, I scroll down a menu of “Fish and Seafood” in my Licious app, and order “Rohu (Rui) Medium – Bengali Cut No Head, (8 – 12 pieces), Serves 4”, priced at ₹249 (₹285) 12% off, to be delivered at a chosen delivery slot the next day (morning 8am – 10am, say) cleaned, and packed in the most aesthetic way that can be directly cooked.

I don’t have to sweat and stand in queues at a stinky crowded fish stall jostling with other sweaty customers seeing dripping blood and scales, and then have an episode of cleaning at home before beginning to cook, after a tired day at office. And of course, I don’t have to make it to the market before it closes by 8pm, and can order my next day’s fish at 1 in the night before going to bed.

So yes, the advantages of such online transactions are arguably many. Who could ever think of buying a dress without trying it on? But we can now, and mostly because of the ‘return policy’ on online purchases – in case it doesn’t fit well or we don’t like a particular aspect, like texture or material, we can just return it for a refund. Such options were rare for something we buy at the store. ‘No return, no refund’ boards would often be displayed quite prominently in garment shops.

A lot of local artisans who were reaching out to a small number of customers are now able to reach out to a larger audience and earn more. Speciality food items (local curries and pickles) are being made as per order by people in Nagaland and the product is being shipped as far as Bangalore. There are many garment manufacturers who are finding a market over Facebook and making money.

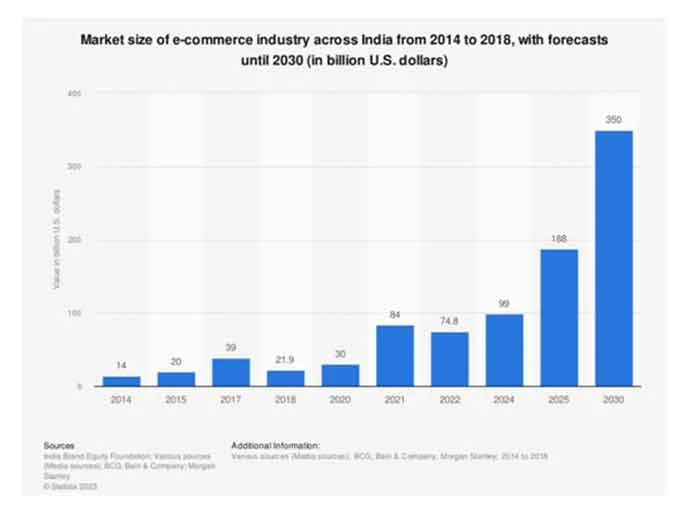

The online shopper base by the year 2026 in India is estimated to be 350 million, from about 150 million in 2021. The population of US is about 332 million. So number of people doing online transactions by 2026 (350 million) in India will be greater than the total population of the US – an exponential growth rate as shown in the following graph:

In the summer of 1994 in Washington, some thirty years back, a youth of about thirty, who had recently resigned from a financial job, sat in the garage of his rented home, and thought about something that all youths probably routinely think – how to minimise regret in old age. All of us have our own ideas of regret. To him regret took the form of not participating in the emerging internet market with his own start-up. Okay, so given people are rapidly using internet, what can he possibly sell that people using the internet, could buy? He considered CDs, computer hardware, computer software, video games and books, but finally settled on books, given the constant demand for literature, the low unit price for books, and the huge number of titles available in print. His parents liked his idea and invested almost $250,000 in the start-up. So opened the largest online bookstore on 16th July 1994 in a garage. And of course, no prizes for guessing we’re talking of the birth of Amazon and Jeff Bezos, its founder.

And most likely we have overlooked the caveat in this story. Only people with access to the internet could even participate in such a market and therefore can avail of the benefits of e-commerce. How many people have such access? In 2020, the figure stands at 90.9% of the population in the US, 92.3% of the population in Canada, but only 43% of the population in India.

But remember, we are a very populated country. So how big is 43% of our population? The population of US in 2020 was 330 million, so 90.9% of that is around 300 million; the population of Canada in 2020 is 38 million, so 92.3% of that is 35 million; India’s population in 2020 is 1396 million, so 43% of that is 600 million. So basically, even with 43% internet penetration, the potential online market in India was twice the size of the American market in 2020. Even the population of Delhi alone now is about 33 million, almost that of the population using internet in the whole of Canada in 2020.

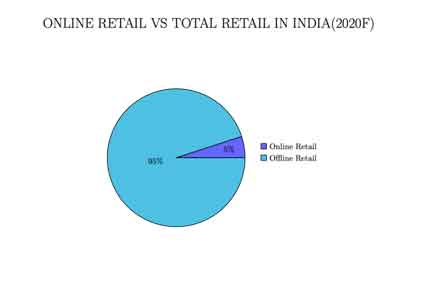

So, even if a small proportion of our country is having access to the internet, and therefore can avail of the benefits that e-commerce offers, we are an absolute treat for Amazon and the like, never mind its suitability for a populated and primarily agricultural country like ours where automation is likely to displace and render several people unemployable. The following pie charts tells the story much more compellingly, which shows the small percentage of online retail vis-a-vis offline retail.

E-commerce hasn’t just delivered fish to me in the most aesthetic way imaginable – it has also displaced Gobindo. Well, displacement may not be the right word if he hasn’t been employed elsewhere. It’s possibly more appropriate to say, he’s been replaced, and we don’t know what he’s doing, if anything at all.

Yuval Noah Harari, in his phenomenal book Homo Deus, argues that human beings are being replaced in several professions all around us. Think of travel agents or insurance agents. They are already obsolete when everyone can purchase tickets and insurances at the clicks of their mobile phones. Stock-exchange trading today is already being managed by computer algorithms, “which can process in a second more data than a human can in a year, and that can react to the data much faster than a human can blink.” How about spotting deceptions merely by observing people’s facial expressions and tone of voice? Lying involves different areas of the brain than used during telling the truth. What if a computer algorithm can see fMRI scans and act as infallible truth machines? “Where will that leave millions of lawyers, judges, cops and detectives?”, questions Harari.

In September 2013 two Oxford researchers, Carl Benedikt Frey and Michael A. Osborne, published ‘The Future of Employment’, in which they studied the likelihood of different professions being taken over by computer algorithms within the next twenty years. They estimated that “47 per cent of US jobs are at high risk. For example, there is a 99 per cent probability that by 2033 human telemarketers and insurance underwriters will lose their jobs to algorithms. There is a 98 per cent probability that the same will happen to sports referees, 97 per cent that it will happen to cashiers and 96 per cent to chefs. Waiters – 94 per cent. Paralegal assistants – 94 per cent. Tour guides – 91 per cent. Bakers – 89 per cent. Bus drivers – 89 per cent. Construction labourers – 88 per cent. Veterinary assistants – 86 per cent. Security guards – 84 per cent. Sailors – 83 per cent. Bartenders – 77 per cent. Archivists – 76 per cent. Carpenters – 72 per cent. Lifeguards – 67 per cent. And so forth.” And the figures are likely to be much worse for India.

Many new professions are also likely to appear, like virtual-world designers. But such professions will probably require much more creativity and flexibility than your run-of-the-mill job. So the crucial problem is not creating new jobs but creating new jobs that humans are better at than algorithms.

What about privacy? Think of the apparently innocuous act of buying a book on Amazon, something that each of us do several times. Well, it tells me something like, you’ve bought these books in the past, people with similar purchases have bought these, so you might like these! Great! There are millions of books in the world and even in the bookstore and I could hardly hope to know about all of them. So wonderful that Amazon knows me and can give me recommendations based on my unique taste.

But this is just the beginning – the beginning of the end of privacy. Today more people read digital books than printed volumes. Harari writes, “Devices such as Amazon’s Kindle are able to collect data on their users while they are reading the book. For example, your Kindle can monitor which parts of the book you read fast, and which slow; on which page you took a break, and on which sentence you abandoned the book, never to pick it up again. (Better tell the author to rewrite that bit.) If Kindle is upgraded with face recognition and biometric sensors, it can know what made you laugh, what made you sad and what made you angry. Soon, books will read you while you are reading them. And whereas you quickly forget most of what you read, Amazon will never forget a thing. Such data will enable Amazon to evaluate the suitability of a book much better than ever before. It will also enable Amazon to know exactly who you are, and how to turn you on and off.” So it is nearly impossible to actually choose the benefits of the system and keeping your privacy intact at the same time.

Gobindo no longer sells fish where he used to. In fact, the entire landscape has transformed beyond recognition. Millions and millions of years ago, when our hunter-gatherer ancestors grew the first crops and discovered agriculture, little did they know that their humble settlements, to be known as villages, will soon become cramped, unhygienic, breeding grounds for epidemics, as well as the blue print of what we know to be modern civilisation. Harari, in his book Sapiens, writes, “The Agricultural Revolution certainly enlarged the sum total of food at the disposal of humankind, but the extra food did not translate into a better diet or more leisure. Rather, it translated into population explosions and pampered elites. The average farmer worked harder than the average forager, and got a worse diet in return. The Agricultural Revolution was history’s biggest fraud.” But of course, no one individual had done anything consciously – for better or for worse, it was a very gradual process that brought small changes at every step leading to the modern times.

Similarly, the currency of e-commerce is basically the money that it churns out, the brand name that is earned, the price of its shares that shoots up. Bezos invented Amazon to satisfy his own ends, not because he wanted people to buy books more conveniently. It led to people buying books more conveniently because it helped to satisfy Bezos’ ends. As a means to an end. Not as an end in itself. Our convenience acted as a stepping stone for his entrepreneurial ends.

Be it the world of entrepreneurship or electronic commerce or science, what Michael Crichton writes in Jurassic Park (about scientists, through Ian Malcolm’s deliberations with Hammond) seems to be equally true for entrepreneurs, “Scientists are actually preoccupied with accomplishment. So they are focused on whether they can do something. They never stop to ask if they should do something.”

And what better to end this essay with, other than the timeless lyrics of Dylan’s everlasting song:

Your old road is rapidly agin’

Please get out of the new one

If you can’t lend your hand

For the times they are a-changin’.

References

Evans, David S., Rivals for Attention: How Competition for Scarce Time Drove the Web Revolution, What it Means for the Mobile Revolution, and the Future of Advertising (February 1, 2014). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2391833 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2391833

Harari, Yuval Noah. 2015. Sapiens. New York, NY: Harper.

Harari, Yuval Noah. 2016. Homo Deus. London, England: Harvill Secker.

Nougarahiya, Shrey, Gaurav Shetty and Dheeraj Mandloi (2021) A Review of E – Commerce in India: The Past, Present, and the Future, Research Review, International Journal of Multidisciplinary 2021; 6(3):12-22, ISSN: 2455-3085 (Online) https://doi.org/10.31305/rrijm.2021.v06.i03.003

Trautman, Lawrence J., E-Commerce, Cyber, and Electronic Payment System Risks: Lessons from PayPal (September 3, 2016). 16 U.C. Davis Business Law Journal 261 (Spring 2016), Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2314119 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2314119

Websites

https://www.ibef.org/industry/e-commerce ( India Brand Equity Foundation)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_Amazon

Soumyanetra Munshi, Associate Professor, Economic Research Unit, Indian Statistical Institute (Kolkata)