Henri Barbusse was a French novelist of the 20th century. Barbusse was upheld as a model of the fight of intellectuals against war and fascism. This year on 17th May, we commemorated his 150th birth anniversary.

Barbusse carved a permanent place amongst the most realistic or sensitive Marxist writers. Few better portrayed the gruesome cruelties or tragedy of war, in the anti-imperialist context. No French writer more articulately defended the Russian Revolution as Barbusse.

His World War I novel, “Le Feu” or “Under Fire,” won in 1916 the French prize for literature, the Prix Goncourt, and carved a place amongst a classic among war literature.

From 1917 to his death, in 1935, Henri Barbusse dedicated himself in activities and writings in defence of the first workers’ state in the world, the USSR.

Barbusse was upheld as a model of the fight of intellectuals against war and fascism.

We need to resurrect writers like Barbusse with wars caused by imperialism inflicting the world as never before and imperialist powers justifying or disguising every anti-people move. An equivalent of ‘Under Fire’ needs to be re-written, in a form relevant for this day and age.

Life sketch

. Born Henri Adrien Gustave Barbusse, the only son of three children, he had a sickly childhood with lung problems. When he was three years old, his English mother died. His father, Adrien Barbusse, was a journalist, who was persecuted for his protestant faith and was politically anti-monarch.

As a teenager, he bid farewell to his rural lifestyle for Paris, abandoning his traditional upbringings.

In 1914 at the start of World War I, he enlisted at the age of 41 into the French Army, serving on the Western Front. Wounded in combat for the third time, he became a victim of pulmonary and gastric illnesses. Unfit to return to combat, he was transferred to a desk position in November of 1915 where he remained instated until the end of the war. For his war service, he was felicitated on June 8, 1915 with the Croix de Guerre with citation.

Before the war, he had written poetry and a novel with little success. Narrating the brutally realistic account of the French Sixth Battalion in the trenches during World War I, Under Fire was his first successful novel. He narrated in vivid detail how half the men in his battalion were eliminated in action Le Feu (translated as Under Fire) based on his life experiences, although some criticised its harsh realism, won the hearts of his former colleagues in the army and he won the Prix Goncourt, France’s most coveted literary award. It was several years after the war that he wrote Les enchaînements (Chains) which is based on his meditation upon the Great War.

“I travelled up the line of beings which, after a hundred thousand years of humanity, ends in me. There is no metempsychosis, no supernatural re-incarnation, no miracle. There is only the positive principle of organic heredity and of memory—that persistent and truly superhuman tracing—that phantasmagoria of the world within the mind which gives to space an inner skin.”

He traces ancient Chaldea and to the days of early Christianity, and to the high middle Ages, and begins to endeavour on the nature of history and of the great men who are remembered for their leadership. The second volume begins on board a ship travelling to Ireland in the decades after the collapse of the Western Roman Empire, and transcends the Italian Renaissance, the colonisation of the Americas, the French Revolution, and the world of the French-held trenches during the Great War.

When his book became ever popular, he had become a pacifist .His next writings were anti-military in the magazine “Clarte’.” In January of 1918, he travelled to Moscow before the collapse of the Russian Empire, where he married a Russian bride. He made a political leap in joining the Bolshevik Party.

He wrote Light from the Abyssi in 1919, Words of a Fighting Man in 1920 and The Knife between My Teethin 1921. In 1919 he published his novel Clate, which was about a clerk working in an office worker who, while serving in the army, understands the merciless crimes of imperialist war.

.He returned to France and joined the French Communist Party in 1923, before travelling back to the Soviet Union. In 1921 he wrote the Esperantist Worker for “Esperanto”, the publication for a left-wing writers’ group, and performed duty as the group’s honorary president for a time.

In his work titled “Russie” (Russia), published by Flammarion in 1930 in Paris, he gives a vivid illustration or evaluation of the first years of the Soviet Union.

This followed with him publishing even more political novels, “Chains” in 1924 and “The Judas of Jesus” in 1927.

He was appointed the editor of the Communist Party’s daily newspaper “L’Humanité” in 1926. Barbusse travelled to the Soviet Union in 1927 as an invited guest for the tenth anniversary of the October Revolution.

In 1928 he pioneered the French weekly communist paper “Monde,” which he edited until his death.

Among others, in 1927 Barbusse participated in the Congress of Friends of the Soviet Union in Moscow. He led the World Congress against Imperialist War (Amsterdam, 1932) and headed the World Committee against War and Fascism, founded in 1933. He was also literary editor for the daily newspaper “l’Humanité” from 1926 to 1929.

In 1932 he led the World Congress against Imperialist War in Amsterdam. In 1935 he wrote “Stalin; A New World Seen through One Man.”

While working on another biography of Stalin, he was diagnosed with pneumonia in addition to his pulmonary war injury and he expired in the Soviet Union.

His remains were returned to Paris for burial with thousands of paying him homage. The workers of the Soviet Union carved a grave marker made from stone from Ural Mountains of Russia, which was sculpted on the front side with the bronze disc of the author’s profile in black marble and red jasper. The next year during the start of the Spanish Civil War, the Henri Barbusse Battalion was formed in his honour as a French International unit.

Character and Impact of Writings

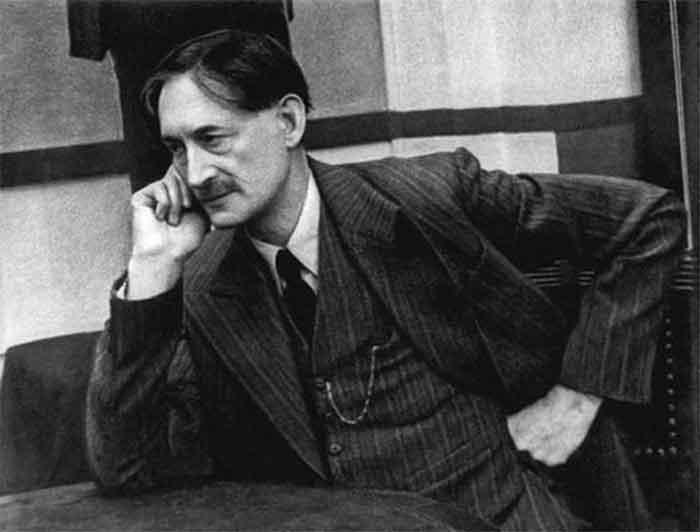

The various summaries in the press on the figure of Henri Barbusse projected him as a dedicated intellectual. In the biographical narratives, in his physical description, and the impact of his lectures and books it is possible to visualise an intellectual and, at the same time, one that turned into a model for the action of his contemporaries.

The sensation of the Clarté endeavour was illustrated in the Southern Cone, especially in the recovery of Barbusse’s biography after his death in August 1935, when the values of the journal were portrayed and the 1920s texts republished. Alongside numerous articles, Barbusse’s death resulted in the flowering of opinion texts in the press in which his trajectory was diagnosed.

Most prevalent in the analyses is the valuing of the experience of radical transformation experienced by the writer: from frivolous writer to critic. In his trajectory the points of vitiation are the First World War, which provided the necessary experience for the establishment of the ‘true’ road of the intellectual.

Also involved was crediting the writer’s trajectory in his direct involvement in political struggles.

Amongst center-left writers, such as the Argentine Aiapeano Alberto Gerchunoff, the gross connection with reality was highlighted in Barbusse’s intellectual endeavours: “What he suffered in the trenches, the sight of immense numbers made into dead meat, heroic meat and stupidly dead and crushed in the mud, gave him the idea of his world magistracy and induced him to transform his work into a militia.” In the US press, similar overtones were expressed: “He was a soldier in France during the World War. He held the ‘World Cross.’ But this phase of his life is in the past. Now he is a soldier who fights for internationalism and world peace.”

A second feature of Barbusse’s trajectory valued in the speeches and texts of anti-fascist intellectuals was the bond or link between life and work, between action and thought. Hermes Lima declared: “His gifts as a writer were so linked to his social action that there is no way to distinguish the revolutionary from the novelist in him.”

The daunting courage of the military aspect of Henri Barbusse was especially highlighted in the texts in the US press. A physically weakened man enlisting voluntarily at the age of 40 to join a regiment of common men in the First World War was saluted as a daunting act of courage for society in that country. “He was wounded on the front three times, but always insisted on returning. He was offered a promotion, but he preferred to remain a common soldier.”

Joseph Freeman, the editor of New Masses who accompanied Barbusse on his US tour, reflected the dichtonomy between the ‘spirit’ of the writer and his physical weakness; the Frenchman repeatedly gave speeches while facing acute fever. Freeman’s after Barbusse’s death stated “The dreams of the artist, the agony of the soldier, faith, reason, and the will of the communist were merged in an almighty being in the crucible of his intense and noble nature. If you saw him moving thousands with his revolutionary message, or talking with an individual worker or veteran of war or writer, you cannot but think: there is a man, there is a poet, and there is a Bolshevik.”

Till the very end of his life, Barbusse would maintain that the Russian Revolution marked a major stride the history of the liberation of humanity. His “Under Fire” has been ranked with such classics as “A Farewell to Arms” and “All Quiet on the Western Front” as one of the most underlining , realistic portrayals of the horrors of war and was translated, like most of his books, into many languages including English.

Barbusse’s writings on USSR Ranked amongst the most illustrative and lucid by any author. Quoting Barbusse “The October Revolution radically overturned social relations and values. It was the gigantic experiment, unprecedented in history: The working class, the mass of the exploited, was taking power into its own hands for the first time in the annals of mankind. The revolution created a new man, the citizen of the labour democracy: Factory worker, field worker, spiritual worker. This new man is at the same time a fighter who is forced to march against currents, destroy remains and build a social monument, the design and materials of which he holds in his hands. The revolution permeated everything: His will, his intellectuality, his spirituality.”

The concoction between Barbusse’s personality and his intellectual activism transformed him into a mascot of intellectual mobilization. For example, the presence of a poster with Barbusse’s face, painted by Antonio Berni, in the 1936 Mayday demonstration in Buenos Aires. The short note in the journal Acadêmica had the same tone: “We who want life, we want life for everyone, and we continue to shout. And our shouts will mean Barbusse as well.”

His writings had overtones of Christian inspiration; which can be derived from Barbusse’s work, Jesus (1927), reflects the human trajectory of the prophet. The Brazilian columnist Aluízio Barata considers him a ‘mystic writer,’ since “Jesus, in the spirit of Barbusse, gives his hand to Marx, and allies with him in the same work of social reconstruction and renovation.”

Harsh Thakor is freelance journalist who has studied lives of Revolutionary Writers. Thanks information from works by Angela Oliviera in “Barbusse: an activist for the international of thought” and ‘Find a grave.com’.